- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

- Asian, Asian-American

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

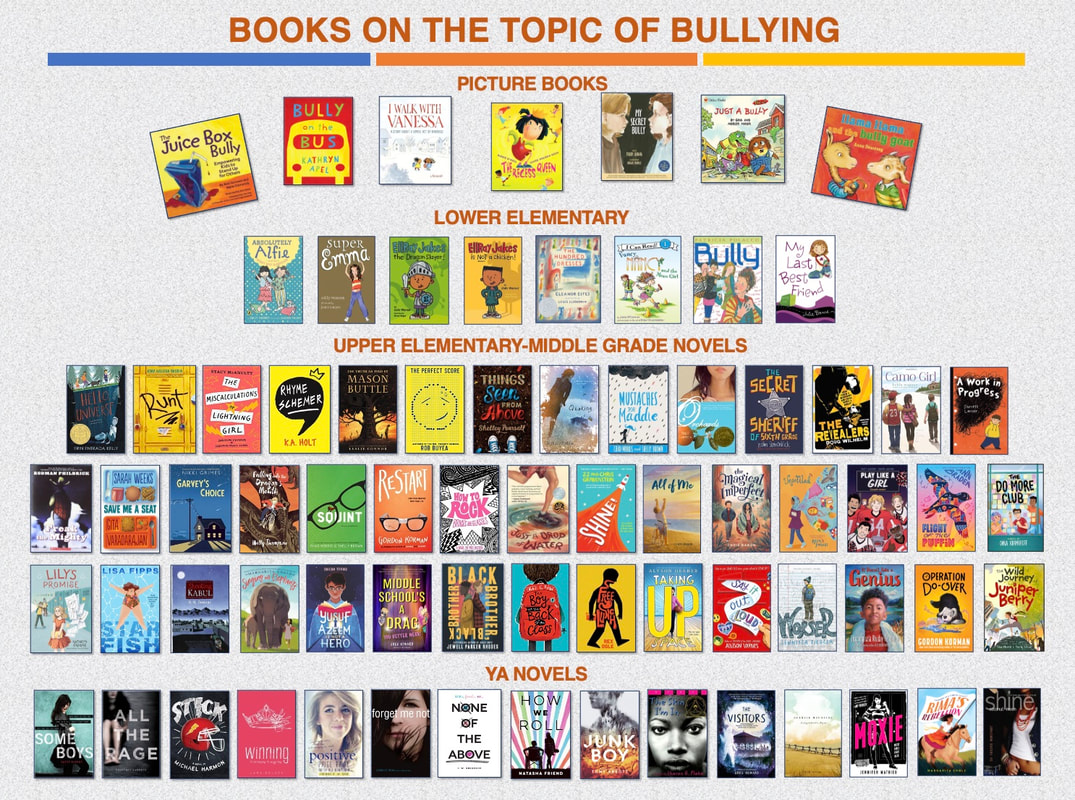

50+ Books to Begin Conversations about BULLYING

Bullying is unwanted, aggressive behavior among school-aged children that involves a real or perceived power imbalance. A type of youth violence that threatens young people’s well-being, bullying can result in physical injuries, social and emotional problems, and academic problems. The harmful effects of bullying are frequently felt by not only the victims, but friends and families, and can hurt the overall health and safety of schools, neighborhoods, and society. A young person can be a perpetrator, a victim, or both. Even youth who have observed but not participated in bullying behavior report significantly more feelings of helplessness and less sense of connection and support from responsible adults (parents/schools) than youth who have not witnessed bullying behavior.

In a comprehensive overview of current bullying prevention research conducted by government and higher education agencies (National Center for Educational Statistics, U.S. Dept of Education and Justin W. Patchin, Ph.D. and Sameer Hinduia, Ph.D. of the Cyberbullying Research Center) , it was found

It is essential that adolescents experience bullying and the effects of bullying, not in real life, but through novels. it is imperative that students, especially middle grade students, read novels about bullying to open conversations about this important topic and to discuss bullies, victims, bystanders, and upstanders, and the ongoing shifts among these roles. Novels can generate important conversations that adolescents need to hold and share truths that they need to know; stories can provide not only a mirror to those who are similar to them—or have faced similar situations—but also windows into those they may view as different from them. But, even more significantly, these novels can serve as maps to guide adolescents in working through conflicts and challenges and maps to help them navigate when they may become lost. Novels can help readers gain knowledge of themselves and empathy for others.

Bullying is unwanted, aggressive behavior among school-aged children that involves a real or perceived power imbalance. A type of youth violence that threatens young people’s well-being, bullying can result in physical injuries, social and emotional problems, and academic problems. The harmful effects of bullying are frequently felt by not only the victims, but friends and families, and can hurt the overall health and safety of schools, neighborhoods, and society. A young person can be a perpetrator, a victim, or both. Even youth who have observed but not participated in bullying behavior report significantly more feelings of helplessness and less sense of connection and support from responsible adults (parents/schools) than youth who have not witnessed bullying behavior.

In a comprehensive overview of current bullying prevention research conducted by government and higher education agencies (National Center for Educational Statistics, U.S. Dept of Education and Justin W. Patchin, Ph.D. and Sameer Hinduia, Ph.D. of the Cyberbullying Research Center) , it was found

- one out of every five (20.2%) students report being bullied.

- a higher percentage of male than of female students report being physically bullied, whereas a higher percentage of female than of male students reported being the subjects of rumors (18% vs. 9%) and being excluded from activities on purpose.

- 41% of students who reported being bullied at school indicated that they think the bullying would happen again.

- of those students who reported being bullied, 13% were made fun of, called names, or insulted; 13% were the subject of rumors; 5% were pushed, shoved, tripped, or spit on; and 5% were excluded from activities on purpose.

- a slightly higher portion of female than of male students report being bullied at school (24% vs. 17%). (

- 46% of bullied students report notifying an adult at school about the incident.

- the reasons for being bullied reported most often by students include physical appearance, race/ethnicity, gender, disability, religion, sexual orientation.

- the federal government began collecting data on school bullying in 2005, when the prevalence of bullying was around 28 percent.

- one in five (20.9%) tweens (9 to 12 years old) has been cyberbullied, cyberbullied others, or seen cyberbullying.

- 49.8% of tweens (9 to 12 years old) said they experienced bullying at school and 14.5% of tweens shared they experienced bullying online.

- Students who experience bullying are at increased risk for depression, anxiety, sleep difficulties, lower academic achievement, and dropping out of school.

- Students who are both targets of bullying and engage in bullying behavior are at greater risk for both mental health and behavior problems than students who only bully or are only bullied.

It is essential that adolescents experience bullying and the effects of bullying, not in real life, but through novels. it is imperative that students, especially middle grade students, read novels about bullying to open conversations about this important topic and to discuss bullies, victims, bystanders, and upstanders, and the ongoing shifts among these roles. Novels can generate important conversations that adolescents need to hold and share truths that they need to know; stories can provide not only a mirror to those who are similar to them—or have faced similar situations—but also windows into those they may view as different from them. But, even more significantly, these novels can serve as maps to guide adolescents in working through conflicts and challenges and maps to help them navigate when they may become lost. Novels can help readers gain knowledge of themselves and empathy for others.

I have previously written about and reviewed 15 of the pictured Upper Elementary, Middle Grade, and YA novels/memoirs for Dr. Bickmore’s YA Wednesday in my guest-blog “Books to Begin Conversations about Bullying, Part 1” (2017)

and 11 more novels in “Books to Begin Conversations about Bullying, Part 2” (2018)

Here I review the 33 additional recently-published Upper Elementary, Middle Grade, and YA novels, written in a variety of formats and featuring diverse characters that I have read in the last 4 years since those two guest-blogs and can recommend. See a list of suggested books for younger readers at the end of the reviews.

and 11 more novels in “Books to Begin Conversations about Bullying, Part 2” (2018)

Here I review the 33 additional recently-published Upper Elementary, Middle Grade, and YA novels, written in a variety of formats and featuring diverse characters that I have read in the last 4 years since those two guest-blogs and can recommend. See a list of suggested books for younger readers at the end of the reviews.

All of Me by Chris Baron (verse novel)

Seventh grader Ari Rosensweig is fat, “so big that everyone stares.” (1) He is made fun of, bullied, called names. One time he is beat up, not even trying to defend himself. But he does make one friend, Pick, the only one who tries to learn the real Ari.

His parents fight. His mother is an artist, and the family moves frequently, his dad managing his mother’s art business. But when they move to the beach for the summer, Ari’s dad leaves and sees Ari infrequently.

“There are times

that you can just be

who you are.

There are also times

when your body betrays you.

There are times when you feel

like you can’t stop eating,

because eating

is the only way

you know

how to

feel

right

again.” (67-68)

But that summer Ari makes two new friends. And as he has let the haters make him into who he is, he now allows Pick, Lisa, and Jorge help him “to find the real me.” (145) He also receives the support of the rabbi who is training him for his Bar Mitzvah, his conversion to manhood under Jewish law. “’Maybe,’ the rabbi says, ‘it’s as simple as believing that you don’t have to be what others want you to be.’” (225)

His mother suggests a diet, but it seems to be a healthy diet and he sheds pounds.

“This doesn’t look like me.

It can’t be me.

I don’t look like this,

normal.” (209)

On a camping trip with Jorge, Ari discards the diet book.

“I don’t see a fat kid,

not anymore.

I simply

see

myself.” (267)

Finally, even though he has gained back some of the pounds (7 of them), he no longer feels like a failure because "it’s not about the weight”; it is about what the summer has brought: adventures, stories, and real friends.

“Just me moving forward,

finding my own way.” (311)

Told in lyrical free verse, this is a story that is needed by so many children. This is not a book about weight; it is the story of identity and friendships—and having power over what you can control.

------------

Seventh grader Ari Rosensweig is fat, “so big that everyone stares.” (1) He is made fun of, bullied, called names. One time he is beat up, not even trying to defend himself. But he does make one friend, Pick, the only one who tries to learn the real Ari.

His parents fight. His mother is an artist, and the family moves frequently, his dad managing his mother’s art business. But when they move to the beach for the summer, Ari’s dad leaves and sees Ari infrequently.

“There are times

that you can just be

who you are.

There are also times

when your body betrays you.

There are times when you feel

like you can’t stop eating,

because eating

is the only way

you know

how to

feel

right

again.” (67-68)

But that summer Ari makes two new friends. And as he has let the haters make him into who he is, he now allows Pick, Lisa, and Jorge help him “to find the real me.” (145) He also receives the support of the rabbi who is training him for his Bar Mitzvah, his conversion to manhood under Jewish law. “’Maybe,’ the rabbi says, ‘it’s as simple as believing that you don’t have to be what others want you to be.’” (225)

His mother suggests a diet, but it seems to be a healthy diet and he sheds pounds.

“This doesn’t look like me.

It can’t be me.

I don’t look like this,

normal.” (209)

On a camping trip with Jorge, Ari discards the diet book.

“I don’t see a fat kid,

not anymore.

I simply

see

myself.” (267)

Finally, even though he has gained back some of the pounds (7 of them), he no longer feels like a failure because "it’s not about the weight”; it is about what the summer has brought: adventures, stories, and real friends.

“Just me moving forward,

finding my own way.” (311)

Told in lyrical free verse, this is a story that is needed by so many children. This is not a book about weight; it is the story of identity and friendships—and having power over what you can control.

------------

Black Brother, Black Brother by Jewell Parker Rhoads

“Be you. Stay confident, visible. Even if others can’t see you.” (183)

Trey and Donte are biracial brothers, but Trey looks like his White father and 7th grader Donte takes after his Black mother. This didn’t seem to matter in their public school in NY where they both had lots of friends, but at Middlefield Prep in Boston, it does. Trey is a popular and respected athlete while Donte is taunted and bullied. Trey stands up for Donte when he can “Ellison brothers stick together” (47), but Alan, the school bully, leads his followers in a chant of “black brother, black brother.” It’s Alan who and wants “other students to see only my blackness. See it as a stain.” (34) and makes “me being darker than my brother a crime.” (44)

When Donte complains, “Everyone here bullies me. Teachers. Students. Whispers, sometimes outright shouts follow me.” (6), not only is Headmaster McGeary not sympathetic, he blames and even punishes him for crimes he has not committed. “Why can’t you be more like your brother?” (8). He calls the police and has Donte taken to jail for slamming his backpack at his own feet in frustration. Released from jail, his mom, a lawyer says, “This is how it starts. Bias. Racism. Plain and simple…” (24)

One option is to “Disappear. Be invisible.” (19), but Donte vows to beat Alan at his own game—fencing. With Trey’s help, he discovers Arden Jones, an African American Olympic fencer who works at the local Boys and Girls Club, and convinces Mr. Jones to coach him. As Donte gets stronger with the help of Coach, Trey, and his new friends at the Boys and Girls Club, he begins to regain a trust in people. “Prejudice is wrong. Wrong, it makes me doubt people.” (87) He learns his Coach’s history and how it is easy to lose oneself in people’s hatred. As Coach tells him when relating his own past failure, “I quit playing because I gave up on me. Became invisible.… Should’ve kept focused on my goals. Should’ve known bullies, biased people, can’t see clearly.” (182) His advice, “Don’t do anything for anyone else, Donte. Do it for you. Only you.” (131)

And most important, through fencing, Coach, his supportive family, and his new friends, Donte learns that he wants to fence, no longer to beat Alan and humiliate him but “to be the best.” (183)

Another powerful novel for 4th though 8th graders by Jewell Parker Rhoads, author of some Ninth Ward, Towers Falling, and Ghost Boys, this short novel, as did Ghost Boys, tackles racism—by adolescents, adults, and society‑head on. The sport of fencing, tied to honor and nobility and promoting good sportsmanship, is particularly appropriate; every fencing bout starts with a salute to your opponent and ends with a handshake.

------------

“Be you. Stay confident, visible. Even if others can’t see you.” (183)

Trey and Donte are biracial brothers, but Trey looks like his White father and 7th grader Donte takes after his Black mother. This didn’t seem to matter in their public school in NY where they both had lots of friends, but at Middlefield Prep in Boston, it does. Trey is a popular and respected athlete while Donte is taunted and bullied. Trey stands up for Donte when he can “Ellison brothers stick together” (47), but Alan, the school bully, leads his followers in a chant of “black brother, black brother.” It’s Alan who and wants “other students to see only my blackness. See it as a stain.” (34) and makes “me being darker than my brother a crime.” (44)

When Donte complains, “Everyone here bullies me. Teachers. Students. Whispers, sometimes outright shouts follow me.” (6), not only is Headmaster McGeary not sympathetic, he blames and even punishes him for crimes he has not committed. “Why can’t you be more like your brother?” (8). He calls the police and has Donte taken to jail for slamming his backpack at his own feet in frustration. Released from jail, his mom, a lawyer says, “This is how it starts. Bias. Racism. Plain and simple…” (24)

One option is to “Disappear. Be invisible.” (19), but Donte vows to beat Alan at his own game—fencing. With Trey’s help, he discovers Arden Jones, an African American Olympic fencer who works at the local Boys and Girls Club, and convinces Mr. Jones to coach him. As Donte gets stronger with the help of Coach, Trey, and his new friends at the Boys and Girls Club, he begins to regain a trust in people. “Prejudice is wrong. Wrong, it makes me doubt people.” (87) He learns his Coach’s history and how it is easy to lose oneself in people’s hatred. As Coach tells him when relating his own past failure, “I quit playing because I gave up on me. Became invisible.… Should’ve kept focused on my goals. Should’ve known bullies, biased people, can’t see clearly.” (182) His advice, “Don’t do anything for anyone else, Donte. Do it for you. Only you.” (131)

And most important, through fencing, Coach, his supportive family, and his new friends, Donte learns that he wants to fence, no longer to beat Alan and humiliate him but “to be the best.” (183)

Another powerful novel for 4th though 8th graders by Jewell Parker Rhoads, author of some Ninth Ward, Towers Falling, and Ghost Boys, this short novel, as did Ghost Boys, tackles racism—by adolescents, adults, and society‑head on. The sport of fencing, tied to honor and nobility and promoting good sportsmanship, is particularly appropriate; every fencing bout starts with a salute to your opponent and ends with a handshake.

------------

Flight of the Puffin by Ann Braden (verse novel)

Four young adolescents on opposite sides of the country; four outsiders who feel alone; four who are connected through one act of kindness that generates multiple acts of support and encouragement that let them, and others, know they are not alone.

Libby comes from a family of bullies—her father, her older brother, and, by all accounts, her grandfather. Her mother and the rest of her family ignore her, making her feel unwelcome in her own home. Her school assumes any actions on her part are acts of bullying, but she is only trying to make her world prettier with paint and glitter. After she finds a rock left by her beloved former art teacher that states, “Create the world of your dreams,” she decides to do just that.

I.

Will.

Not.

Be.

Like.

Them. (11)

When Libby is given some index cards and colored pencils for a class essay assignment, she instead makes cards with pictures and positive sayings, such as “You are amazing.” (13) She decides to pass them out to “to “anybody who needs it…. Like if someone gets bullied and they’re feeling alone, then maybe this can help them remember that the bully isn’t always right.”(103) She makes more cards of encouragement and, grounded by her parents, even climbs out the window to distribute her cards. “What kind of person would sneak out into the rain to leave index cards around town for nobody in particular? A person who doesn’t have a choice.” (176)

Vincent is a seventh grader, across the country in Seattle, who doesn’t fit in, not at school and not at home where his single mother wants him to be more creative. Vincent is interested in triangles and puffins and being accepted for himself. But the boys at school bully him and call him a “girl,” like that is a negative thing. “I’m not trans, and I’m not gay. And I’m not a girl. It’s like T said. I’m just me.” (161)

T also lives in Seattle where they and their dog Peko live on the streets, having run away from a family who does not accept them.

It’s possible to keep going.

Keep

going

for longer than what

anyone else

would expect. (79)

But flying away

doesn’t solve everything. (143)

Also living in rural Vermont in a town near Libby, Jack, a 7th grader, is still grieving the accidental death of his younger brother Alex—Alex who loved glitter and butterflies. Jack has become a big brother to the younger students and a helper to the administrators of his 2-room school and, when the grant that is keeping his school afloat is threatened, he vows to save it. But he does not understand the state’s insistence on a gender-neutral bathroom, and he finds himself standing up for something that begins to feel wrong. When he becomes embroiled in a public debate, he finds his supporters to be those people he does not admire, and he begins to question his views and those of his family. Finally discussing Alex with his mother, Jack says, “What if a boy doesn’t want to do boy things? Or doesn’t always feel like a boy? Or even…doesn’t feel like a boy or a girl?” (194)

Libby hears about Vincent and mails him one of her notes. Vincent meets T on the streets when T helps Vincent who then brings food to T and Peko. As Vincent learns more about them , he receives advice on how to stand up to bullies (”I don’t have to be scared. I don’t have to feel bad. I don’t have to feel like I am less than them.”).

And when Vincent sees Jack on the news, he “reaches out from across the country” by mail to tell him about T and advises that there may be kids in Jack’s school who are transgender “but don’t say.” When Vincent offers his support, Jack realizes, as do all four,

I am simultaneously understanding two things…

That I have been alone.

And that I don’t have to be. (171)

This is a story about the importance of communication and validation as the four young adolescents connect with each other but also with their own family members, changing perspectives and values. It is a compelling, simply-told story of identity and the power of being oneself. Many readers will recognize themselves in these characters and their families and communities, and other readers will learn about those they may someday meet or might already know, hiding in plain sight in their classrooms or neighborhoods. This is a wonderful, much-needed novel about empathy, support, and standing up for ourselves and others.

------------

Four young adolescents on opposite sides of the country; four outsiders who feel alone; four who are connected through one act of kindness that generates multiple acts of support and encouragement that let them, and others, know they are not alone.

Libby comes from a family of bullies—her father, her older brother, and, by all accounts, her grandfather. Her mother and the rest of her family ignore her, making her feel unwelcome in her own home. Her school assumes any actions on her part are acts of bullying, but she is only trying to make her world prettier with paint and glitter. After she finds a rock left by her beloved former art teacher that states, “Create the world of your dreams,” she decides to do just that.

I.

Will.

Not.

Be.

Like.

Them. (11)

When Libby is given some index cards and colored pencils for a class essay assignment, she instead makes cards with pictures and positive sayings, such as “You are amazing.” (13) She decides to pass them out to “to “anybody who needs it…. Like if someone gets bullied and they’re feeling alone, then maybe this can help them remember that the bully isn’t always right.”(103) She makes more cards of encouragement and, grounded by her parents, even climbs out the window to distribute her cards. “What kind of person would sneak out into the rain to leave index cards around town for nobody in particular? A person who doesn’t have a choice.” (176)

Vincent is a seventh grader, across the country in Seattle, who doesn’t fit in, not at school and not at home where his single mother wants him to be more creative. Vincent is interested in triangles and puffins and being accepted for himself. But the boys at school bully him and call him a “girl,” like that is a negative thing. “I’m not trans, and I’m not gay. And I’m not a girl. It’s like T said. I’m just me.” (161)

T also lives in Seattle where they and their dog Peko live on the streets, having run away from a family who does not accept them.

It’s possible to keep going.

Keep

going

for longer than what

anyone else

would expect. (79)

But flying away

doesn’t solve everything. (143)

Also living in rural Vermont in a town near Libby, Jack, a 7th grader, is still grieving the accidental death of his younger brother Alex—Alex who loved glitter and butterflies. Jack has become a big brother to the younger students and a helper to the administrators of his 2-room school and, when the grant that is keeping his school afloat is threatened, he vows to save it. But he does not understand the state’s insistence on a gender-neutral bathroom, and he finds himself standing up for something that begins to feel wrong. When he becomes embroiled in a public debate, he finds his supporters to be those people he does not admire, and he begins to question his views and those of his family. Finally discussing Alex with his mother, Jack says, “What if a boy doesn’t want to do boy things? Or doesn’t always feel like a boy? Or even…doesn’t feel like a boy or a girl?” (194)

Libby hears about Vincent and mails him one of her notes. Vincent meets T on the streets when T helps Vincent who then brings food to T and Peko. As Vincent learns more about them , he receives advice on how to stand up to bullies (”I don’t have to be scared. I don’t have to feel bad. I don’t have to feel like I am less than them.”).

And when Vincent sees Jack on the news, he “reaches out from across the country” by mail to tell him about T and advises that there may be kids in Jack’s school who are transgender “but don’t say.” When Vincent offers his support, Jack realizes, as do all four,

I am simultaneously understanding two things…

That I have been alone.

And that I don’t have to be. (171)

This is a story about the importance of communication and validation as the four young adolescents connect with each other but also with their own family members, changing perspectives and values. It is a compelling, simply-told story of identity and the power of being oneself. Many readers will recognize themselves in these characters and their families and communities, and other readers will learn about those they may someday meet or might already know, hiding in plain sight in their classrooms or neighborhoods. This is a wonderful, much-needed novel about empathy, support, and standing up for ourselves and others.

------------

Free Lunch by Rex Ogle

On the first day of middle school Rex Ogle arrives at school with a black eye and his name in the Free Lunch Program registry. This was supposed to be a great year. “I guess it won’t be after all.” (25)

When his friends all join the football team, Rex has no one to sit with at lunch. “Having a place to sit in middle school is important. ‘Cause it means you have friends. Popular kids sit at one table. Football players sit nearby. Cheerleaders too. Band kids are in one area, school newspaper and yearbook kids at another. Religious kids have a table. So do the kids who play Dungeons & Dragons. The whole cafeteria is that way. Everyone has their place. Everyone except me.” (56)

As Rex lives through a year of avoiding being hit by his mentally-unstable mother and her abusive boyfriend; taking care of his little brother; sleeping in a room with only a sleeping bag; having his one possession—his Sony boombox, a present from his real dad—pawned; surviving a teacher who treats him as “less than;” and moving to government-subsidized housing in view of the school, he still feels the responsibility to help his mother. When his friend Liam steals some candy at the grocery “because [he] can,” the cashier asks to see Rex’s pockets, and Rex learns the double standard for the wealthy and the poor. “I don’t get why folks act like being poor is a disease, like it’s wrong or something.” (53)

On the positive side, Rex makes a new friend at school, Ethan, a boy who may have seems a “total weirdo” at first but turns out to be a good person and true friend and have his own family problems, and Rex’s teacher learns to admit and face her own prejudices. Rex comes to the realization that “Mom didn’t sign me up for the Free Lunch Program to punish me. She did it so I could have food….Things are not as black and white as I thought. Maybe some things are gray, somewhere in between.” (188)

Rex’s mother finally obtains a job, and he even receives a present for Christmas. “I may not have a million presents, but I have one. And one is better than none.” (188) As Ethan tells him, “…no one has a perfect life. There is no such thing as ‘perfect.’ It’s just an idea.” (195)

.

However, some lives are indeed less perfect. About 15 million children in the United States – 21% of all children – live in families with incomes below the federal poverty threshold. Forty-three percent of children live in families who earn less than necessary to cover basic expenses (NCCP). And Rex Ogle, author, was one of them—and Free Lunch is his personal story.

------------

On the first day of middle school Rex Ogle arrives at school with a black eye and his name in the Free Lunch Program registry. This was supposed to be a great year. “I guess it won’t be after all.” (25)

When his friends all join the football team, Rex has no one to sit with at lunch. “Having a place to sit in middle school is important. ‘Cause it means you have friends. Popular kids sit at one table. Football players sit nearby. Cheerleaders too. Band kids are in one area, school newspaper and yearbook kids at another. Religious kids have a table. So do the kids who play Dungeons & Dragons. The whole cafeteria is that way. Everyone has their place. Everyone except me.” (56)

As Rex lives through a year of avoiding being hit by his mentally-unstable mother and her abusive boyfriend; taking care of his little brother; sleeping in a room with only a sleeping bag; having his one possession—his Sony boombox, a present from his real dad—pawned; surviving a teacher who treats him as “less than;” and moving to government-subsidized housing in view of the school, he still feels the responsibility to help his mother. When his friend Liam steals some candy at the grocery “because [he] can,” the cashier asks to see Rex’s pockets, and Rex learns the double standard for the wealthy and the poor. “I don’t get why folks act like being poor is a disease, like it’s wrong or something.” (53)

On the positive side, Rex makes a new friend at school, Ethan, a boy who may have seems a “total weirdo” at first but turns out to be a good person and true friend and have his own family problems, and Rex’s teacher learns to admit and face her own prejudices. Rex comes to the realization that “Mom didn’t sign me up for the Free Lunch Program to punish me. She did it so I could have food….Things are not as black and white as I thought. Maybe some things are gray, somewhere in between.” (188)

Rex’s mother finally obtains a job, and he even receives a present for Christmas. “I may not have a million presents, but I have one. And one is better than none.” (188) As Ethan tells him, “…no one has a perfect life. There is no such thing as ‘perfect.’ It’s just an idea.” (195)

.

However, some lives are indeed less perfect. About 15 million children in the United States – 21% of all children – live in families with incomes below the federal poverty threshold. Forty-three percent of children live in families who earn less than necessary to cover basic expenses (NCCP). And Rex Ogle, author, was one of them—and Free Lunch is his personal story.

------------

It Doesn’t Take a Genius by Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich

“I don’t even like debate, to be honest. But I’m good at it, and I learned early on that’s what matters. People love a winner. When you win, everyone sees you. And if people don’t see you, maybe you’re not really there.” (8)

Thirteen-year-old Emmett Charles is a winner, or at least at his school where his vocabulary, three debate trophies, science fair award, and Spelling Bee record have him feeling he might even be a genius.

And when his social skills and small size fail him, his older brother Luke is always there to bail him out , especially with Mac, his bully. “Luke has come out of nowhere. Like a superhero. He’s even taller than Mac, wears his shirts a little small so girls can peep his muscles, and his fade is tight and gleaming.” (6-7) “Sometimes it feels like I’m in a river, and the current’s real strong. And I have a choice between clinging to a rock and getting left behind, or letting myself get swept up in it and carried along without any control. Luke’s my rock.” (138)

But when his brother Luke gets a scholarship to a private art school in Maine for his last year of high school, summer is all Emmett, or E as he wants to be called, will have for Luke to turn him back into a winner after he passed on competing in this year’s debate championship. “We’re a team. Batman and Robin.” (29)

But when he discovers that Luke has gotten a job as a junior counselor at Camp DuBois, a historic Black summer camp in New York, and Emmett schemes to get himself a scholarship to attend as a camper. When he arrives he discovers that

“What my friends, and my family for that matter, don’t seem to understand is that I don’t swim. I guess they get the fact that I can’t. But they keep thinking that I will, one day. That I even want to. And they’re WRONG. Dad was supposed to teach me, and he’s not here.” (19) Emmett’s father died when he was 5, and Like and his mother don’t discuss his father with him which saddens him. In fact, seeing other kids with their dads sadden him.

And most important he discovers, as Natasha says, “It doesn’t take a genius to be a friend.” (291)

E’s story is filled with great characters: the socially-awkward Charles who can “do you” the best I have seen; Charles’ love interest and budding playwright Michelle, Emmett’s crush Natasha who does win at everything but is just as happy when the camp director decides there will be no final competitions; the alleged-bully Derek who is able to spend more time with Luke than Emmett does, but, as is often the case, is more complex than presumed; and the assortment of other campers, counselors, and group leaders. Readers will learn not only a lot of Black history but the importance of studying one’s cultural roots.

There will be adolescents in the classroom and community who need to read this book. I know that I learned quite a lot which led me to want to know more‑about Black culture and my culture and the cultures of others.

------------

“I don’t even like debate, to be honest. But I’m good at it, and I learned early on that’s what matters. People love a winner. When you win, everyone sees you. And if people don’t see you, maybe you’re not really there.” (8)

Thirteen-year-old Emmett Charles is a winner, or at least at his school where his vocabulary, three debate trophies, science fair award, and Spelling Bee record have him feeling he might even be a genius.

And when his social skills and small size fail him, his older brother Luke is always there to bail him out , especially with Mac, his bully. “Luke has come out of nowhere. Like a superhero. He’s even taller than Mac, wears his shirts a little small so girls can peep his muscles, and his fade is tight and gleaming.” (6-7) “Sometimes it feels like I’m in a river, and the current’s real strong. And I have a choice between clinging to a rock and getting left behind, or letting myself get swept up in it and carried along without any control. Luke’s my rock.” (138)

But when his brother Luke gets a scholarship to a private art school in Maine for his last year of high school, summer is all Emmett, or E as he wants to be called, will have for Luke to turn him back into a winner after he passed on competing in this year’s debate championship. “We’re a team. Batman and Robin.” (29)

But when he discovers that Luke has gotten a job as a junior counselor at Camp DuBois, a historic Black summer camp in New York, and Emmett schemes to get himself a scholarship to attend as a camper. When he arrives he discovers that

- His brother will be too busy to spend any time with him

- The camp is filled with “geniuses” and nerds—and new friends who have his back

- He will be discovering more of his culture and history through classes like “Black to the Future” and the camp focuses on community, not individual success. He finally realizes that “DuBois is preparing me for something more than bubble tests, more than I’d ever thought it would.” (190)

- Even though he is a great dancer, he is an even better choreographer

- Although he sees himself as a winner, without effort and spreading himself too thin, he can lose, more than he thought

- He will have to take swimming lessons (with the Littles) and pass a swimming test

“What my friends, and my family for that matter, don’t seem to understand is that I don’t swim. I guess they get the fact that I can’t. But they keep thinking that I will, one day. That I even want to. And they’re WRONG. Dad was supposed to teach me, and he’s not here.” (19) Emmett’s father died when he was 5, and Like and his mother don’t discuss his father with him which saddens him. In fact, seeing other kids with their dads sadden him.

And most important he discovers, as Natasha says, “It doesn’t take a genius to be a friend.” (291)

E’s story is filled with great characters: the socially-awkward Charles who can “do you” the best I have seen; Charles’ love interest and budding playwright Michelle, Emmett’s crush Natasha who does win at everything but is just as happy when the camp director decides there will be no final competitions; the alleged-bully Derek who is able to spend more time with Luke than Emmett does, but, as is often the case, is more complex than presumed; and the assortment of other campers, counselors, and group leaders. Readers will learn not only a lot of Black history but the importance of studying one’s cultural roots.

There will be adolescents in the classroom and community who need to read this book. I know that I learned quite a lot which led me to want to know more‑about Black culture and my culture and the cultures of others.

------------

Junk Boy by Tony Abbott (verse novel)

Junk Boy introduces readers to two teen outliers, two dysfunctional families, two stories which become intertwined.

there is no putting

a tree back up after

it’s broken

and fallen

in a storm

maybe with us

with people

it’s different (336)

Bobby Lang, nicknamed Junk by the bullies at school because he lives in a place that has become a junkyard, spends his time flying under the radar, eyes down, not speaking. His father is drunk, abusive, unemployed, and listens to sad country songs; his mother left when he was a baby is, according to his father, is dead. Bobby has no self-confidence and little self-worth but then he meets Rachel, a talented artist who sees something else in him.

her eyes could

somehow see a me

that is more me

than I am

that is so weirdly more

so better than

actual

me (273-4)

But Rachel has her own family problems. Her father has just moved out and her physically-abusive mother wants the local priest to “reformat” Rachel who is gay.

As Rachel moves in and out of Bobby’s life, her need helps him figure out

what was I going to

say

do

be? (274)

And what he is, or becomes, is a rescuer and protector, a savior. As Father Percy tells him, “It’s what she found in you…” (352)

Reading Tony Abbott’s first verse novel, I felt like I was watching a movie unfold as I followed the protagonist on his Hero’s Journey.

------------

Junk Boy introduces readers to two teen outliers, two dysfunctional families, two stories which become intertwined.

there is no putting

a tree back up after

it’s broken

and fallen

in a storm

maybe with us

with people

it’s different (336)

Bobby Lang, nicknamed Junk by the bullies at school because he lives in a place that has become a junkyard, spends his time flying under the radar, eyes down, not speaking. His father is drunk, abusive, unemployed, and listens to sad country songs; his mother left when he was a baby is, according to his father, is dead. Bobby has no self-confidence and little self-worth but then he meets Rachel, a talented artist who sees something else in him.

her eyes could

somehow see a me

that is more me

than I am

that is so weirdly more

so better than

actual

me (273-4)

But Rachel has her own family problems. Her father has just moved out and her physically-abusive mother wants the local priest to “reformat” Rachel who is gay.

As Rachel moves in and out of Bobby’s life, her need helps him figure out

what was I going to

say

do

be? (274)

And what he is, or becomes, is a rescuer and protector, a savior. As Father Percy tells him, “It’s what she found in you…” (352)

Reading Tony Abbott’s first verse novel, I felt like I was watching a movie unfold as I followed the protagonist on his Hero’s Journey.

------------

Lily’s Promise by Kathryn Erskine

Sixth grader Lily, painfully shy, is attending public school for the first time. She had always been homeschooled by her father, and, before he died, he encouraged her talk to other kids “Girls make excellent friends” and left her a Strive for Five challenge: “to speak up, make herself heard, step out of her ‘comfort zone’ at least five times… and pretty soon, it [will] become second nature.’ (18-19)

On the first day Lily, overwhelmed at the noise and rudeness of the students, (1) makes her first friend, Hobart (not a girl) and (2) observes many instances of bullying, some against Hobart (and even the new teacher) and most generated from Ryan and his followers. During the year as she forms a group of new friends from those students many others would think different, she finds her courage and voice to become an upstander, rather than a bystander, earning her the five charms left by her father. Lily and her new friends influence both young adolescents and adults, such as Hobart’s father, alike.

One unique and very compelling element are the chapters narrated by Libro (the book) is it reflects on the characters and events of the preceding chapter and on the author (Imaginer) herself.

[Spoiler alert] While many readers may be dismayed by the open ending, it provides an opportunity for deep discussions and will generate important conversations, one reason I would encourage this book for collaborative reading in literature circles or as a whole-class selection even though still enjoyable as independent reading. In a class setting, readers could write their own endings, possibly putting themselves in the place of Lily.

------------

Sixth grader Lily, painfully shy, is attending public school for the first time. She had always been homeschooled by her father, and, before he died, he encouraged her talk to other kids “Girls make excellent friends” and left her a Strive for Five challenge: “to speak up, make herself heard, step out of her ‘comfort zone’ at least five times… and pretty soon, it [will] become second nature.’ (18-19)

On the first day Lily, overwhelmed at the noise and rudeness of the students, (1) makes her first friend, Hobart (not a girl) and (2) observes many instances of bullying, some against Hobart (and even the new teacher) and most generated from Ryan and his followers. During the year as she forms a group of new friends from those students many others would think different, she finds her courage and voice to become an upstander, rather than a bystander, earning her the five charms left by her father. Lily and her new friends influence both young adolescents and adults, such as Hobart’s father, alike.

One unique and very compelling element are the chapters narrated by Libro (the book) is it reflects on the characters and events of the preceding chapter and on the author (Imaginer) herself.

[Spoiler alert] While many readers may be dismayed by the open ending, it provides an opportunity for deep discussions and will generate important conversations, one reason I would encourage this book for collaborative reading in literature circles or as a whole-class selection even though still enjoyable as independent reading. In a class setting, readers could write their own endings, possibly putting themselves in the place of Lily.

------------

Middle School’s a Drag; You Better Werk by Greg Howard

“Maybe Pap isn’t the person I’ve been trying to impress all this time. Maybe it was me. Maybe what I really need is to be proud of myself.” (236)

A 13-year-old drag queen; a rising comic learning the difference between insults and jokes; a three-legged blind rescue dog; a wheelchair-bound Super Hero impersonator; a dream interpreter; two best friends that offer support no matter what—and, right in the middle, their Talent Agent, rising entrepreneur Michael Pruitt of Anything Talent and Pizzazz (not Pizza) Agency.

Seventh grader Mikey (as he is called when he is out of the office) has been planning businesses, most of which have failed, to impress his beloved Pap, the original family entrepreneur who is now in a nursing home with diabetes and heart problems. His Board consists of his very supportive mother and father and his less-supportive, evil, client-stealing younger sister, Lyla. When Mickey meets Coco Caliente, Mistress of Madness and Mayhem (boy name Julian Vasquez) at school, he has found his new business.

Mikey thinks he might be—no, he knows that he is—gay, but he has only come out to his parents (“They were wicked cool about it right from the beginning.” (30)) and his two best friends although, for some unfathomable reason, the school bullies call him Gay Mikey. However, he worries that he is not good at being gay, has no gaydar, and is sure that he is not ready to like-like someone. Then he meets Julian’s friend, new student Colton Sanford whose smile makes his stomach melt. Julian, who has become a friend, tells him, “Michael, there’s no right or wrong way to be gay.” (95)

Michael spends the next weeks Googling performance terms, trying to book paying gigs for his clients, and preparing them for the school talent show where he can earn a commission if a client wins the $100 prize. And navigating the school bullies.

As Mikey, he discovers the secret of head bully Tommy Jenrette which ends up improving their relationship, and he supports Julian’s whose mother and abuela are encouraging but his father absolutely forbids him to dress up. “I just wish my dad could be proud of me,” Julian says, his shoulders sagging. “Like he used to be—before Coco Caliente.” ((94)

Mikey also encourages and defends Colton who tells him that he moved in with his grandmother because his mother is in rehab. “I guess you just never know what’s going on with someone, even if they seem okay and wear a mask that’s nice to look at.” (231) Mickey is good at letting his friends appreciate that they matter. “I think about my business ventures and how they make me feel important. And like I matter. And wanting to matter doesn’t seem like too much to ask.” (94)

The characters, especially Mickey/Michael, grabbed me on page 1. “I think CEOs of big-time companies like mine shouldn’t be required to attend middle school. It seriously gets in the way of doing important business stuff.” Middle School’s a Drag is hilarious, the writing voice jumping right off the pages. I didn’t put it down, and neither will readers. This is a book for reluctant readers, proficient readers, and the many adolescents who need to know that they matter.

------------

“Maybe Pap isn’t the person I’ve been trying to impress all this time. Maybe it was me. Maybe what I really need is to be proud of myself.” (236)

A 13-year-old drag queen; a rising comic learning the difference between insults and jokes; a three-legged blind rescue dog; a wheelchair-bound Super Hero impersonator; a dream interpreter; two best friends that offer support no matter what—and, right in the middle, their Talent Agent, rising entrepreneur Michael Pruitt of Anything Talent and Pizzazz (not Pizza) Agency.

Seventh grader Mikey (as he is called when he is out of the office) has been planning businesses, most of which have failed, to impress his beloved Pap, the original family entrepreneur who is now in a nursing home with diabetes and heart problems. His Board consists of his very supportive mother and father and his less-supportive, evil, client-stealing younger sister, Lyla. When Mickey meets Coco Caliente, Mistress of Madness and Mayhem (boy name Julian Vasquez) at school, he has found his new business.

Mikey thinks he might be—no, he knows that he is—gay, but he has only come out to his parents (“They were wicked cool about it right from the beginning.” (30)) and his two best friends although, for some unfathomable reason, the school bullies call him Gay Mikey. However, he worries that he is not good at being gay, has no gaydar, and is sure that he is not ready to like-like someone. Then he meets Julian’s friend, new student Colton Sanford whose smile makes his stomach melt. Julian, who has become a friend, tells him, “Michael, there’s no right or wrong way to be gay.” (95)

Michael spends the next weeks Googling performance terms, trying to book paying gigs for his clients, and preparing them for the school talent show where he can earn a commission if a client wins the $100 prize. And navigating the school bullies.

As Mikey, he discovers the secret of head bully Tommy Jenrette which ends up improving their relationship, and he supports Julian’s whose mother and abuela are encouraging but his father absolutely forbids him to dress up. “I just wish my dad could be proud of me,” Julian says, his shoulders sagging. “Like he used to be—before Coco Caliente.” ((94)

Mikey also encourages and defends Colton who tells him that he moved in with his grandmother because his mother is in rehab. “I guess you just never know what’s going on with someone, even if they seem okay and wear a mask that’s nice to look at.” (231) Mickey is good at letting his friends appreciate that they matter. “I think about my business ventures and how they make me feel important. And like I matter. And wanting to matter doesn’t seem like too much to ask.” (94)

The characters, especially Mickey/Michael, grabbed me on page 1. “I think CEOs of big-time companies like mine shouldn’t be required to attend middle school. It seriously gets in the way of doing important business stuff.” Middle School’s a Drag is hilarious, the writing voice jumping right off the pages. I didn’t put it down, and neither will readers. This is a book for reluctant readers, proficient readers, and the many adolescents who need to know that they matter.

------------

Moxie by Jennifer Mathieu

“moxie”- force of character, determination, nerve.

Testosterone, football, and the football players run East Rockport High School in a small Texas town. All monies are funneled to the football team, and “Make me a sandwich” is the boys’ code for telling girls to stay in their place (even during classes). While girls are subject to humiliating dress code checks, football players get away with T-shirts displaying crude sexist rhetoric. Good girl, don’t-rock-the-boat Vivian, the daughter of a feminist, at least in her own high school days, has had enough and anonymously begins creating and posting vines from a group called Moxie, encouraging the high school girls to take action.

As some girls eagerly join the movement—bake and craft sales for the girls’ soccer team, protests of the Dress Code crackdowns, and labeling the lockers of boys who subject them to a Bump 'n' Grab “game," others are concerned about the ramifications of joining, and it is not until a rape attempt by the star football player, son of the principal—is disregarded that most of the high school girls—and a few boys—cross popularity and racial barriers and find their Moxie. “It occurs to me that this is what it means to be a feminist. Not a humanist or an equalist or whatever. But a feminist. It’s not a bad word. After today it might be my favorite word. Because really all it is is girls supporting each other and wanting to be treated like human beings in a world that’s always finding ways to tell them they’re not.” (p.269).

------------

“moxie”- force of character, determination, nerve.

Testosterone, football, and the football players run East Rockport High School in a small Texas town. All monies are funneled to the football team, and “Make me a sandwich” is the boys’ code for telling girls to stay in their place (even during classes). While girls are subject to humiliating dress code checks, football players get away with T-shirts displaying crude sexist rhetoric. Good girl, don’t-rock-the-boat Vivian, the daughter of a feminist, at least in her own high school days, has had enough and anonymously begins creating and posting vines from a group called Moxie, encouraging the high school girls to take action.

As some girls eagerly join the movement—bake and craft sales for the girls’ soccer team, protests of the Dress Code crackdowns, and labeling the lockers of boys who subject them to a Bump 'n' Grab “game," others are concerned about the ramifications of joining, and it is not until a rape attempt by the star football player, son of the principal—is disregarded that most of the high school girls—and a few boys—cross popularity and racial barriers and find their Moxie. “It occurs to me that this is what it means to be a feminist. Not a humanist or an equalist or whatever. But a feminist. It’s not a bad word. After today it might be my favorite word. Because really all it is is girls supporting each other and wanting to be treated like human beings in a world that’s always finding ways to tell them they’re not.” (p.269).

------------

October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard by Leslea Newman (verse novel)

October 12, 1998

Somebody entered this world with a cry;

Somebody left without saying goodbye. (35)

On the night of October 6, 1998, Matthew Shepard, a gay 21-year-old college student was lured from a Wyoming bar by two young homophobic men, brutally beaten, tied to a remote fence, and left to die. October Mourning is Lesléa Newman’s tribute in the form of a collection of sixty-eight poems about Matthew Shepard and his murder.

Newman recreates the events of the night, the following days, and the court case and reimagines thoughts and conversations through a variety of perspectives: those of Matthew Shepard himself, the people of the town—the bartender, a doctor, the patrol officers, Russell Henderson and Aaron McKinney and their girlfriends—as well as inanimate objects, notably beginning and ending with the fence to which Shepard was tied. Many of the poems are introduced with a quote from a person involved in the events.

A range of emotions is shared through a variety of poetic styles: free verse, haiku, pantoum, concrete, rhymed, list, alphabet, villanelle, acrostic, and poems modeled after the poetry of other poets.

The poetry of October Mourning serves to let the reader bear witness to Matthew Shepard and his death but also to the power of poetry to express loss and grief and as a response to injustice. Heartbreaking and moving, but emotional and a call to action, this is a story that should be shared with all adolescents.

"Only if each of us imagines that what happened to Matthew Shepard could happen to any one of us will we be motivated to do something. And something must be done." (Imagine, 90)

From “Then and Now”

Then I was a son

Now I am a symbol

Then a was a person.

Now I am a memory.

Then I was a student.

Now I am a lesson. (40)

------------

October 12, 1998

Somebody entered this world with a cry;

Somebody left without saying goodbye. (35)

On the night of October 6, 1998, Matthew Shepard, a gay 21-year-old college student was lured from a Wyoming bar by two young homophobic men, brutally beaten, tied to a remote fence, and left to die. October Mourning is Lesléa Newman’s tribute in the form of a collection of sixty-eight poems about Matthew Shepard and his murder.

Newman recreates the events of the night, the following days, and the court case and reimagines thoughts and conversations through a variety of perspectives: those of Matthew Shepard himself, the people of the town—the bartender, a doctor, the patrol officers, Russell Henderson and Aaron McKinney and their girlfriends—as well as inanimate objects, notably beginning and ending with the fence to which Shepard was tied. Many of the poems are introduced with a quote from a person involved in the events.

A range of emotions is shared through a variety of poetic styles: free verse, haiku, pantoum, concrete, rhymed, list, alphabet, villanelle, acrostic, and poems modeled after the poetry of other poets.

The poetry of October Mourning serves to let the reader bear witness to Matthew Shepard and his death but also to the power of poetry to express loss and grief and as a response to injustice. Heartbreaking and moving, but emotional and a call to action, this is a story that should be shared with all adolescents.

"Only if each of us imagines that what happened to Matthew Shepard could happen to any one of us will we be motivated to do something. And something must be done." (Imagine, 90)

From “Then and Now”

Then I was a son

Now I am a symbol

Then a was a person.

Now I am a memory.

Then I was a student.

Now I am a lesson. (40)

------------

Operation Do-Over by Gordon Korman

I’ve already seen that everything in my life doesn’t have to go exactly the way it went the first time around. (123)

Who has never wished for a “Do Over”? Sometimes it is something little, like a golf swing or studying for that test, but sometimes it is a major event, something that has affected our life.

Mason and Ty were best friends from age three or even before that, before they even knew what “friends” were. They were actually even closer than best friends, finishing each other’s sentences and “We can look at each other and crack up laughing at a joke neither of us has to say out loud.” (8-9) Both considered nerds, bullied by Dominic and Miggy, interested in school—especially science—and obsessed with time travel. “TY and I may not be cool, but we’ve got each other’s backs one thousand percent. Plus, we’re smart, so it’s hard to imagine that there’s anything middle school could throw at us that we can’t handle.” (11) But in seventh grade, it did—a new student, Ava Petrakis.

Ava turns out to be the nicest, prettiest, smartest girl, and she is popular with everyone, but she chooses to spend time with Mason and Ty. Realizing they both have a crush on Ava, they make a pact not to pursue their interest. But when Mason and Ava kiss at the Harvest Festival, the friendship ends.

Five years later, Mason and Ty are still not friends and an incident occurs which has far-reaching repercussions. After a car accident Mason ends up going back in time to his 12-year-old self with a chance at a Do-Over. Having studied time travel for years, Mason knows that he has to be careful how his actions affect the future, but he just can’t resist making some changes. Can he save his parents’ marriage; can he train his beloved dog not to run into the path of a Roto-Rooter truck; can he actually earn the respect of the class bullies; and, most important, can he avoid Ava and keep his friendship with Ty?

Well-written with humor and pathos, featuring engaging characters (male and female) and a protagonist-narrator whom readers will champion from the beginning through his “two futures,” this novel has everything: a plot with twists and turns, bullies, nerds, football players, (and those who perform dual roles), time travel, crushes, and a dog. Spanning Mason’s 7th grade and 12th grade lives, Gordon Korman writes this one for readers of all ages.

------------

I’ve already seen that everything in my life doesn’t have to go exactly the way it went the first time around. (123)

Who has never wished for a “Do Over”? Sometimes it is something little, like a golf swing or studying for that test, but sometimes it is a major event, something that has affected our life.

Mason and Ty were best friends from age three or even before that, before they even knew what “friends” were. They were actually even closer than best friends, finishing each other’s sentences and “We can look at each other and crack up laughing at a joke neither of us has to say out loud.” (8-9) Both considered nerds, bullied by Dominic and Miggy, interested in school—especially science—and obsessed with time travel. “TY and I may not be cool, but we’ve got each other’s backs one thousand percent. Plus, we’re smart, so it’s hard to imagine that there’s anything middle school could throw at us that we can’t handle.” (11) But in seventh grade, it did—a new student, Ava Petrakis.

Ava turns out to be the nicest, prettiest, smartest girl, and she is popular with everyone, but she chooses to spend time with Mason and Ty. Realizing they both have a crush on Ava, they make a pact not to pursue their interest. But when Mason and Ava kiss at the Harvest Festival, the friendship ends.

Five years later, Mason and Ty are still not friends and an incident occurs which has far-reaching repercussions. After a car accident Mason ends up going back in time to his 12-year-old self with a chance at a Do-Over. Having studied time travel for years, Mason knows that he has to be careful how his actions affect the future, but he just can’t resist making some changes. Can he save his parents’ marriage; can he train his beloved dog not to run into the path of a Roto-Rooter truck; can he actually earn the respect of the class bullies; and, most important, can he avoid Ava and keep his friendship with Ty?

Well-written with humor and pathos, featuring engaging characters (male and female) and a protagonist-narrator whom readers will champion from the beginning through his “two futures,” this novel has everything: a plot with twists and turns, bullies, nerds, football players, (and those who perform dual roles), time travel, crushes, and a dog. Spanning Mason’s 7th grade and 12th grade lives, Gordon Korman writes this one for readers of all ages.

------------

Play Like a Girl by Misty Wilson (graphic memoir)

“Even though friends were kind of confusing, at least football ALWAYS made sense.” (135)

Misty, a super-competitive athletic, was always challenging the boys in feats of strength and endurance. But, in the summer before seventh grade, she was surprised, when deciding to play for the town’s football league, that even her friends on the team did not support her decision. When Cole said, “‘Football really isn’t a sport for girls’…not a single one of them was sticking up for me.” (7)

Undeterred, Misty joins the team and talks her best friend Bree into joining also. But Bree quits and starts hanging around with the popular Mean Girl Ava, and when Misty tries to change to be more “girly” like the two (a hilarious try at makeup), they still make fun of her, and Misty realizes, with Bree gone, she has no friends.

She throws herself into football and, as she wins over many of her male team members, she is befriended by two of the cheerleaders who appear to accept her, and like her, just as she is. “Middle school was complicated. But I knew one thing for sure: I was done trying to be someone else.” (258)

Misty Wilson’s graphic memoir (illustrated by husband David Wilson) shares her story of football, family, middle-grade friends and frenenemies—and empowerment and identity. I also learned a lot about football, the positions and the plays—especially from the illustrations—that I wish I had known when watching games as a teen and a mother of a player.

------------

“Even though friends were kind of confusing, at least football ALWAYS made sense.” (135)

Misty, a super-competitive athletic, was always challenging the boys in feats of strength and endurance. But, in the summer before seventh grade, she was surprised, when deciding to play for the town’s football league, that even her friends on the team did not support her decision. When Cole said, “‘Football really isn’t a sport for girls’…not a single one of them was sticking up for me.” (7)

Undeterred, Misty joins the team and talks her best friend Bree into joining also. But Bree quits and starts hanging around with the popular Mean Girl Ava, and when Misty tries to change to be more “girly” like the two (a hilarious try at makeup), they still make fun of her, and Misty realizes, with Bree gone, she has no friends.

She throws herself into football and, as she wins over many of her male team members, she is befriended by two of the cheerleaders who appear to accept her, and like her, just as she is. “Middle school was complicated. But I knew one thing for sure: I was done trying to be someone else.” (258)

Misty Wilson’s graphic memoir (illustrated by husband David Wilson) shares her story of football, family, middle-grade friends and frenenemies—and empowerment and identity. I also learned a lot about football, the positions and the plays—especially from the illustrations—that I wish I had known when watching games as a teen and a mother of a player.

------------

Rima’s Rebellion: Courage in a Time of Tyranny

by Margarita Engle (verse novel)

I dream of being legitimate

My father would love me,

society could accept me,

strangers might even admire

my short, simple first name

if it were followed

by two surnames

instead of

one. (53)

Twelve-year-old Rima Marin is a “natural child,” the illegitimate child of a father who will not acknowledge her.

I am a living, breathing secret.

Natural children aren’t supposed to exist.

Our names don’t appear on family trees,

our framed photos never rest affectionately

beside a father’s armchair, and when priests

write about us in official documents,

they follow the single surname of a mother

with the letters SOA,

meaning sin otro apellido,

so that anyone reading

will understand clearly

that without two last names

we have no legal right to money

for school uniforms, books, papers, pencils,

shelter,

or food. (11)

Rima, her Mama, and her abuela live in poverty, squatting in a small building owned by her wealthy father. Her mother is a lacemaker and her abulela—a nurse during the wars for independence from Spain—works as a farrier and founded La Mambisa Voting Club whose members are fighting for voting rights, equality for “natural children,” and the end of the Adultery Law which permits men to kill unfaithful wives and daughters along with their lovers.

Taking place from 1923 to 1936, Rima also joins La Mambisas; becomes friends with her acknowledged, wealthy half-sister, keeping her safe when she defies their father, refusing arranged marriage and becomes pregnant by her boyfriend; falls in love; and becomes trained as a typesetter, printing revolutionary books and posters for suffrage.

Over the thirteen years she grows from a girl who cowers from bullies who call her “bastarda,” finding confidence only in riding Ala, her buttermilk mare, to an adolescent, living in the city and fighting dictatorship with words—hers and others:

absorb[ing] the strength of female hopes,

wondering if this is how it will be

someday

when women

can finally

vote.(43)

to a young married woman and mother voting in her first election:

Voting rights are our only

Pathway to freedom from fear. (A167)

------------

by Margarita Engle (verse novel)

I dream of being legitimate

My father would love me,

society could accept me,

strangers might even admire

my short, simple first name

if it were followed

by two surnames

instead of

one. (53)

Twelve-year-old Rima Marin is a “natural child,” the illegitimate child of a father who will not acknowledge her.

I am a living, breathing secret.

Natural children aren’t supposed to exist.

Our names don’t appear on family trees,

our framed photos never rest affectionately

beside a father’s armchair, and when priests

write about us in official documents,

they follow the single surname of a mother

with the letters SOA,

meaning sin otro apellido,

so that anyone reading

will understand clearly

that without two last names

we have no legal right to money

for school uniforms, books, papers, pencils,

shelter,

or food. (11)

Rima, her Mama, and her abuela live in poverty, squatting in a small building owned by her wealthy father. Her mother is a lacemaker and her abulela—a nurse during the wars for independence from Spain—works as a farrier and founded La Mambisa Voting Club whose members are fighting for voting rights, equality for “natural children,” and the end of the Adultery Law which permits men to kill unfaithful wives and daughters along with their lovers.

Taking place from 1923 to 1936, Rima also joins La Mambisas; becomes friends with her acknowledged, wealthy half-sister, keeping her safe when she defies their father, refusing arranged marriage and becomes pregnant by her boyfriend; falls in love; and becomes trained as a typesetter, printing revolutionary books and posters for suffrage.

Over the thirteen years she grows from a girl who cowers from bullies who call her “bastarda,” finding confidence only in riding Ala, her buttermilk mare, to an adolescent, living in the city and fighting dictatorship with words—hers and others:

absorb[ing] the strength of female hopes,

wondering if this is how it will be

someday

when women

can finally

vote.(43)

to a young married woman and mother voting in her first election:

Voting rights are our only

Pathway to freedom from fear. (A167)

------------

Say It Out Loud by Allison Varnes

“So you left the only real friend you had to avoid getting picked on.” (140)

After Tristan and Josh cause problems on the school bus, teasing everyone and putting gum in Ben’s hair, sixth-grader Charlotte Andrews’ best friend Maddie goes to the principal. The boys retaliate by focusing their bullying on her. Afraid of being bullied herself, Charlotte walks past their seat and abandons Maddie. When it becomes clear that Maddie no longer considers her a friend, she feels guilty but doesn’t have the courage to fix things. Charlotte continues to stand wordlessly by as the bullying becomes worse.

Charlotte has always been nervous about speaking out loud because of her stutter. “I hate the moment when someone realizes I’m different. It changes the way they look at me.” (11) Maddie was the one person, besides her parents, who ignored her stutter.

Since she cannot think of any way to make Maddie feel better, Charlotte starts writing encouraging notes to other students, first to Ben and then to random students. “…I don’t sign them with my real name. No one is going to care where they came from. It’s the words that matter.” (127) The note writing campaign spreads. “Did I cause this? Is that even possible? I’ve left so many notes all over the school. Could it be that my words inspired other kids to leave notes of their own?” (230)

Meanwhile her mother makes Charlotte take the musical drama class and, even though she has a beautiful voice, she flubs her audition for her favorite musical The Wizard of Oz and is cast in two minor roles. But she has a great attitude: “I still wish I had a role where I could at least get a little glammed up, but watching the other kids get into their costumes reminds me that every role is important. And I’m going to be the best apple tree and horse’s butt there ever was.” (174-5)

And even when the snobbish Aubrey, who is cast in the role she wanted, is mean to her, Charlotte leaves her a supportive note. “It’s so hard to give her a compliment when she was horrible about me trying out for Glinda. But this is about making her feel better, not my hurt feelings. Even if it is hard to say, I know I still have to be kind.” (105)

When the drama program is threatened, Charlotte using her new note-writing strategy to organize a letter writing campaign by The Wizard Of Oz cast and crew, finding her voice.

And she finds the courage to speak out and right her wrong, moving from a bystander to an upstander. “If I’d just had the courage to stand by my friend in the first place, things would be so different. I wasted too much time being afraid.” (238)

This is a novel that needs to be in every classroom, school, and community library for grades 5-8. It can be effectively grouped with other books about bullying, a critical topic for middle school conversations. It is imperative that students, especially middle grade students, read novels about bullying to open conversations about this important topic and to discuss bullies, victims, bystanders, and upstanders, and the ongoing shifts among these roles.

------------

“So you left the only real friend you had to avoid getting picked on.” (140)

After Tristan and Josh cause problems on the school bus, teasing everyone and putting gum in Ben’s hair, sixth-grader Charlotte Andrews’ best friend Maddie goes to the principal. The boys retaliate by focusing their bullying on her. Afraid of being bullied herself, Charlotte walks past their seat and abandons Maddie. When it becomes clear that Maddie no longer considers her a friend, she feels guilty but doesn’t have the courage to fix things. Charlotte continues to stand wordlessly by as the bullying becomes worse.

Charlotte has always been nervous about speaking out loud because of her stutter. “I hate the moment when someone realizes I’m different. It changes the way they look at me.” (11) Maddie was the one person, besides her parents, who ignored her stutter.

Since she cannot think of any way to make Maddie feel better, Charlotte starts writing encouraging notes to other students, first to Ben and then to random students. “…I don’t sign them with my real name. No one is going to care where they came from. It’s the words that matter.” (127) The note writing campaign spreads. “Did I cause this? Is that even possible? I’ve left so many notes all over the school. Could it be that my words inspired other kids to leave notes of their own?” (230)

Meanwhile her mother makes Charlotte take the musical drama class and, even though she has a beautiful voice, she flubs her audition for her favorite musical The Wizard of Oz and is cast in two minor roles. But she has a great attitude: “I still wish I had a role where I could at least get a little glammed up, but watching the other kids get into their costumes reminds me that every role is important. And I’m going to be the best apple tree and horse’s butt there ever was.” (174-5)

And even when the snobbish Aubrey, who is cast in the role she wanted, is mean to her, Charlotte leaves her a supportive note. “It’s so hard to give her a compliment when she was horrible about me trying out for Glinda. But this is about making her feel better, not my hurt feelings. Even if it is hard to say, I know I still have to be kind.” (105)

When the drama program is threatened, Charlotte using her new note-writing strategy to organize a letter writing campaign by The Wizard Of Oz cast and crew, finding her voice.

And she finds the courage to speak out and right her wrong, moving from a bystander to an upstander. “If I’d just had the courage to stand by my friend in the first place, things would be so different. I wasted too much time being afraid.” (238)

This is a novel that needs to be in every classroom, school, and community library for grades 5-8. It can be effectively grouped with other books about bullying, a critical topic for middle school conversations. It is imperative that students, especially middle grade students, read novels about bullying to open conversations about this important topic and to discuss bullies, victims, bystanders, and upstanders, and the ongoing shifts among these roles.

------------

Shine! by J.J. and Chris Grabenstein

“How do we use the stars when we wish to journey safely into the vast unknown? It’s simple, really…. We just need to find one star…. The one that’s always constant and true.” (174)

Shine! really does shine. This is a valuable story about how adolescents can shine just by being their best selves. It is a story of the importance of kindness and caring for others.

Seventh grader Piper Milly lives with her father, a music teacher (and hopeful Broadway show composer), her mother having died when she was three years old. In the middle of the school year, her father is offered a position at a prestigious private school for the offspring of the very wealthy. Along with the position comes free tuition for Piper who knows she will not fit in. Her mother had also been a scholarship student at Chumley Prep but was an extremely talented cellist, her name is on a plaque at the school. Piper feels she has no special abilities—certainly no musical talent, and with her frayed shirt collars and inexpensive shoes, she won’t fit in with girls who buy their accessories at the ritzy Winterset Collection.

Shunned from the beginning by Ansleigh Braden-Hammerschmidt, Mean Girl extraordinaire, and her band of followers which include most of their grade, Piper finds three good friends, and together they become the Hibbleflitts: a math whiz, a magician, a comedian, and Piper, an astronomy “geek.” When their English teacher tasks the class with journaling about who they want to be, not in the future but now, and the students compete for the new Excelsior award, Piper feels she does not excel in anything, excelling being the only defined criteria for the award, and she is not sure who she wants herself to be—Does she want to super-talented like her mother, a singer like Brooke, a limit-pusher, the award winner?

As she navigates the year, facing multiple challenges, helping strangers and friends alike, and trying to figure out where and how she might excel and who she wants to be, Piper finds she can shine by being the person she already is, maybe finding that star or maybe being that star for others.

------------