- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

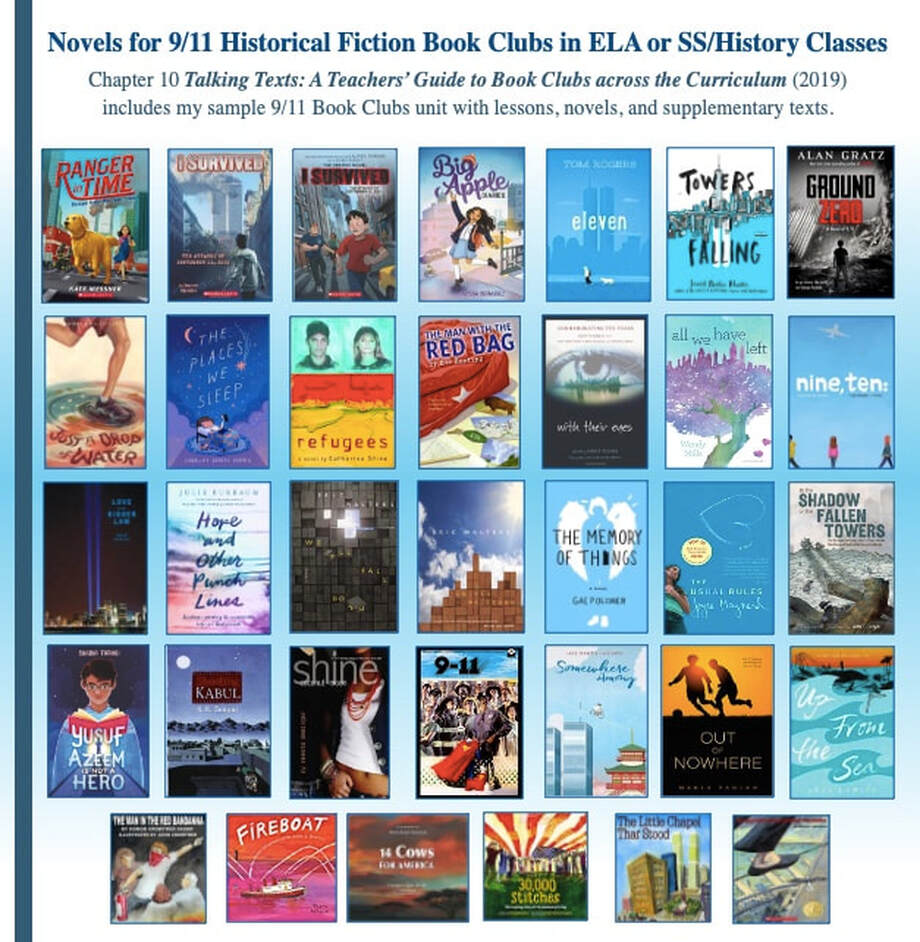

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

- Asian, Asian-American

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

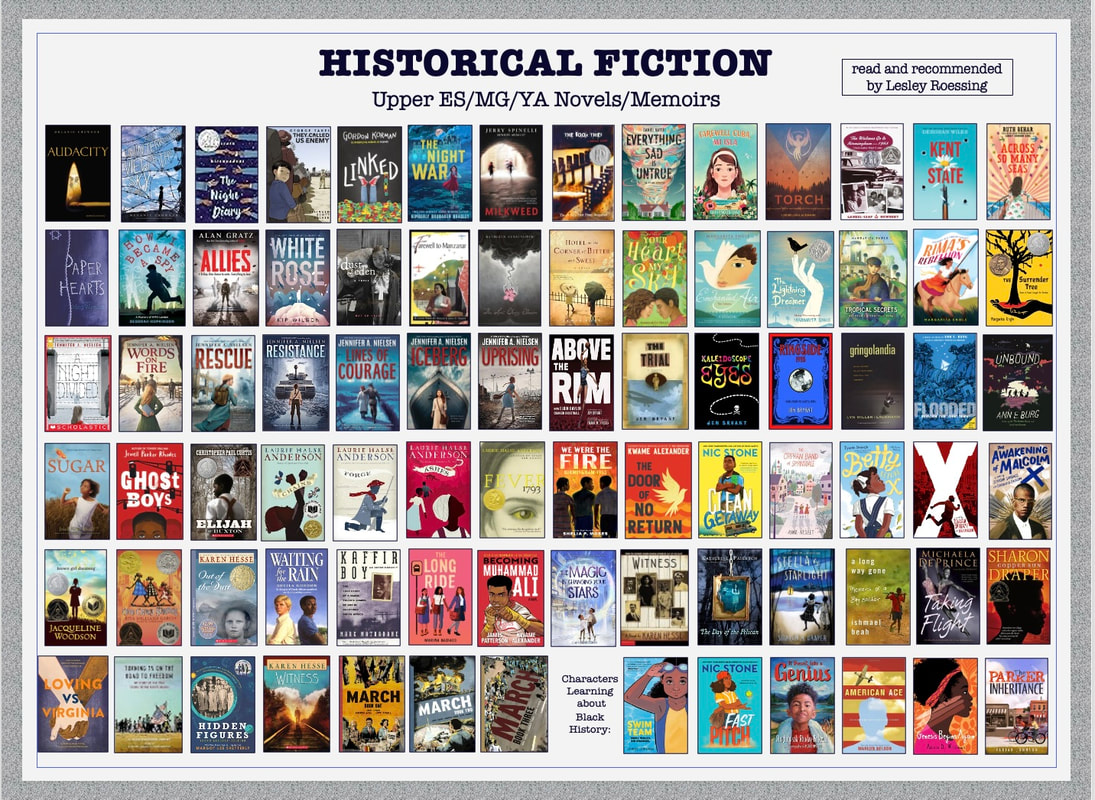

LEARNING HISTORY through STORY: MG/YA HISTORICAL FICTION NOVELS

One of the most effective ways to learn about any historical event, and the nuances and effects of those events, is through novel study—the power of story. Every historical event is distinct and affects people and places uniquely—and each is surrounded by misconceptions, misunderstandings, miscommunications, and differing and shifting perspectives. We may learn about history through textbooks and lectures, but we experience history through novels. And when we live it, we learn it; we do not merely learn about it. We discern the complex issues, and we feel empathy for all affected. We bear witness to the events we read and the plights of the people affected by those events.

I continue to read, and learn from, some amazing novels which can be read as whole-class, book club, or individual texts to learn more about history in English, Language Arts, and Social Studies classes. A suggestion for Social Studies classes would be for Book Clubs to each read a novel from a time period or location studied in class so that groups can present “their” historic event to the class and the class can compare and contrast the novels, the events, and the discerned effects of these events on the characters.

One of the most effective ways to learn about any historical event, and the nuances and effects of those events, is through novel study—the power of story. Every historical event is distinct and affects people and places uniquely—and each is surrounded by misconceptions, misunderstandings, miscommunications, and differing and shifting perspectives. We may learn about history through textbooks and lectures, but we experience history through novels. And when we live it, we learn it; we do not merely learn about it. We discern the complex issues, and we feel empathy for all affected. We bear witness to the events we read and the plights of the people affected by those events.

I continue to read, and learn from, some amazing novels which can be read as whole-class, book club, or individual texts to learn more about history in English, Language Arts, and Social Studies classes. A suggestion for Social Studies classes would be for Book Clubs to each read a novel from a time period or location studied in class so that groups can present “their” historic event to the class and the class can compare and contrast the novels, the events, and the discerned effects of these events on the characters.

Audacity*; An Uninterrupted View of the Sky*; The Night Diary*; They Called Us Enemy; Linked;The Night War*; Milkweed; The Book Thief; Everything Sad Is Untrue*; Farewell Cuba, Mi Isla*; Torch*; The Watson’s Go to Birmingham-1963; Kent State*; Across So Many Seas*; Paper Hearts; How I Became a Spy;*; Allies*; White Rose*; Dust of Eden; Farewell, Manzanar; The Last Cherry Blossom*; The Hotel at the Corner of Bitter and Sweet*; Your Heart-My Sky*; Enchanted Air*; The Lightning Dreamer*; Tropical Secrets*; The Surrender Tree*; A Night Divided*; Words on Fire*; Rescue*; Resistance; Lines of Courage*; Iceberg*; Uprising*; Above the Rim*; The Trial*; Kaleidoscope Eyes*; Ringside, 1925*; Gringolandia*; Flooded*; Unbound*; Sugar; Ghost Boys*; Elijah of Buxton; Chains; Forged; Ashes; Fever, 1793; We Were the Fire-Birmingham, 1963*; The Door of No Return; Clean Getaway; The Orphan Band of Springdale*; Betty Before X; X, A Novel*, The Awakening of Malcolm X; Brown Girl Dreaming; One Crazy Summer; Out of the Dust; Waiting for the Rain; Kafir Boy; The Long Ride*; Becoming Muhammad Ali*; The Magic in Changing Your Stars; Witness; Day of the Pelican; Stella and Starlight; A Long Way Gone; Taking Flight; Copper Sun; Loving vs Virginia*; Turning 15 on the Road to Freedom*; March Book One; March Book Two; March Book Three; Swim Team*; Fast Pitch*; It Doesn’t Take a Genius*; American Ace; Genesis Begins Again*; The Parker Inheritance

*Asterisked titles are reviewed alphabetically

Audacity*; An Uninterrupted View of the Sky*; The Night Diary*; They Called Us Enemy; Linked;The Night War*; Milkweed; The Book Thief; Everything Sad Is Untrue*; Farewell Cuba, Mi Isla*; Torch*; The Watson’s Go to Birmingham-1963; Kent State*; Across So Many Seas*; Paper Hearts; How I Became a Spy;*; Allies*; White Rose*; Dust of Eden; Farewell, Manzanar; The Last Cherry Blossom*; The Hotel at the Corner of Bitter and Sweet*; Your Heart-My Sky*; Enchanted Air*; The Lightning Dreamer*; Tropical Secrets*; The Surrender Tree*; A Night Divided*; Words on Fire*; Rescue*; Resistance; Lines of Courage*; Iceberg*; Uprising*; Above the Rim*; The Trial*; Kaleidoscope Eyes*; Ringside, 1925*; Gringolandia*; Flooded*; Unbound*; Sugar; Ghost Boys*; Elijah of Buxton; Chains; Forged; Ashes; Fever, 1793; We Were the Fire-Birmingham, 1963*; The Door of No Return; Clean Getaway; The Orphan Band of Springdale*; Betty Before X; X, A Novel*, The Awakening of Malcolm X; Brown Girl Dreaming; One Crazy Summer; Out of the Dust; Waiting for the Rain; Kafir Boy; The Long Ride*; Becoming Muhammad Ali*; The Magic in Changing Your Stars; Witness; Day of the Pelican; Stella and Starlight; A Long Way Gone; Taking Flight; Copper Sun; Loving vs Virginia*; Turning 15 on the Road to Freedom*; March Book One; March Book Two; March Book Three; Swim Team*; Fast Pitch*; It Doesn’t Take a Genius*; American Ace; Genesis Begins Again*; The Parker Inheritance

*Asterisked titles are reviewed alphabetically

Below are reviews of 70 of my more-recently-read historical fiction including a separate section below for Novels, Memoirs, and Graphics about the Events of Nine Eleven.

A Night Divided by Jennifer A. Nielsen

I remember when the Berlin Wall came down, but I did not really understand the story of its building and how it affected those on either side until reading A Night Divided.

In 1961 Germany—Russia controlled the East; Britain, US and France controlled the West. Gerta, her brother Fritz, and their mother live in East Berlin. Papa and brother Dominic had gone on a short trip to the West. On August 13 the wall went up—overnight—and one family, as were many, was divided. Twelve-year-old Gerta longed for her family and for freedom and a future.

“It wasn’t things I longed for…. I wanted books that weren’t censored.…I wanted a home without hidden microphones, and friends and neighbors I could talk to without wondering if they would report me to the secret police. And I wanted control over my own life, the chance to succeed” (125).

One day Gerta sees Dominic and father on the other side and interprets their message to dig a tunnel under the Death Strip to the West. Bravely, she and her brother Fritz risk everything—their friendships and even their lives—to try to reach safety and reunite their family.

A Night Divided is a narrative of events in history, but it is also a story of family and the bravery of even adolescents.

-----

I remember when the Berlin Wall came down, but I did not really understand the story of its building and how it affected those on either side until reading A Night Divided.

In 1961 Germany—Russia controlled the East; Britain, US and France controlled the West. Gerta, her brother Fritz, and their mother live in East Berlin. Papa and brother Dominic had gone on a short trip to the West. On August 13 the wall went up—overnight—and one family, as were many, was divided. Twelve-year-old Gerta longed for her family and for freedom and a future.

“It wasn’t things I longed for…. I wanted books that weren’t censored.…I wanted a home without hidden microphones, and friends and neighbors I could talk to without wondering if they would report me to the secret police. And I wanted control over my own life, the chance to succeed” (125).

One day Gerta sees Dominic and father on the other side and interprets their message to dig a tunnel under the Death Strip to the West. Bravely, she and her brother Fritz risk everything—their friendships and even their lives—to try to reach safety and reunite their family.

A Night Divided is a narrative of events in history, but it is also a story of family and the bravery of even adolescents.

-----

Above the Rim: How Elgin Baylor Changed Basketball by Jen F. Bryant

“In one smooth move, like a plane taking off,

He leaped…

Higher and higher and higher--

As if pulled by some invisible wire,

And just when it seemed he’d have to come down,

No!

He’d HANG there, suspended, floating like a bird or a cloud,

Changing direction, shifting the ball to the other side,

Twisting in midair, slashing, crashing,

Gliding past the defense, up—up—above the rim.”

Above the Rim is the story of NBA player Elgin Baylor and how he changed basketball, but it is also the story of Civil Rights in the United States and how Elgin contributed to that movement.

Readers follow Elgin from age 14 when he began playing basketball “in a field down the street” to college ball at the College of Idaho to becoming the #1 draft pick for the Minneapolis Lakers (later the LA Lakers) to being named 1959 NBA Rookie of the Year. At the same time readers follow the peaceful protests of Rosa Parks, the Little Rock Nine, and the African American college students sitting at the “whites only” Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, NC.

In his first season Baylor sat out a game to protest the hotel and restaurants serving “whites only,” leading the NBA commissioner to make an anti-discrimination rule. “Elgin had already changed the way basketball was played. Now by sitting down and NOT playing, he helped change things off court.”

“Artists [such as Baylor,] change how we see things, how we perceive human limits, and how we define ourselves and our culture.” (Author’s Note)

This picture book, exquisitely illustrated by Frank Morrison, belongs in every classroom and home library for readers of all ages. Lyrically written in free verse by Jen Bryant, it would serve as a mentor text for many writing focus lessons:

Following the story, the author provides a lengthy Author’s Note about Baylor, a bibliography of Further Reading, and a 1934-2018 Timeline of Elgin’s life, black athletes, and Civil Rights highlights.

-----

“In one smooth move, like a plane taking off,

He leaped…

Higher and higher and higher--

As if pulled by some invisible wire,

And just when it seemed he’d have to come down,

No!

He’d HANG there, suspended, floating like a bird or a cloud,

Changing direction, shifting the ball to the other side,

Twisting in midair, slashing, crashing,

Gliding past the defense, up—up—above the rim.”

Above the Rim is the story of NBA player Elgin Baylor and how he changed basketball, but it is also the story of Civil Rights in the United States and how Elgin contributed to that movement.

Readers follow Elgin from age 14 when he began playing basketball “in a field down the street” to college ball at the College of Idaho to becoming the #1 draft pick for the Minneapolis Lakers (later the LA Lakers) to being named 1959 NBA Rookie of the Year. At the same time readers follow the peaceful protests of Rosa Parks, the Little Rock Nine, and the African American college students sitting at the “whites only” Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, NC.

In his first season Baylor sat out a game to protest the hotel and restaurants serving “whites only,” leading the NBA commissioner to make an anti-discrimination rule. “Elgin had already changed the way basketball was played. Now by sitting down and NOT playing, he helped change things off court.”

“Artists [such as Baylor,] change how we see things, how we perceive human limits, and how we define ourselves and our culture.” (Author’s Note)

This picture book, exquisitely illustrated by Frank Morrison, belongs in every classroom and home library for readers of all ages. Lyrically written in free verse by Jen Bryant, it would serve as a mentor text for many writing focus lessons:

- repetition, free verse, and rhyming lines for musicality

- technical language (jargon), i.e., hanging jumper, spin-shot, backboard

- active verbs, i.e., gliding, shifting, floating, twisted, reverse dunked

- Figurative language, i.e., floating like a bird or a cloud

- Sensory details, i.e., steamy summer day, padlocked fences, clickety-clack trains, flick of his wrist, beds that were too short, cold food

Following the story, the author provides a lengthy Author’s Note about Baylor, a bibliography of Further Reading, and a 1934-2018 Timeline of Elgin’s life, black athletes, and Civil Rights highlights.

-----

Across So Many Seas by Ruth Behar

“I feel like I carry a lot of history on my shoulders. Not only were my ancestors driven out of Spain, but my abuela had to leave Turkey, and my parents had to leave Cuba. So many seas were crossed.”—Paloma, 2003 (ARC 201)

There are numerous parts of history that we do not learn—or at least I didn’t learn until I visited foreign lands through travel and novels. There are many reasons why people emigrate to other lands—sometimes it is political; other times the catalyst is religious persecution; and sometimes the cause is being sent away by family members—and sometimes we cross the sea to discover our ancestral homeland. The characters in Ruth Behar’s new novel who travel across so many seas do so for many of these reasons.

The family saga begins in 1492 in Toledo formerly “known as the city of three cultures [where] Jews, Muslims, and Christians lived together peacefully for centuries.” (ARC 212). However, the Spanish Inquisition first persecuted the Muslims, turning mosques into cathedrals, and then the Jews who are threatened with the choice of conversion or hanging. Benvenida, her two brothers, and her parents are forced to leave Toledo and walk for days to the coast, carrying a few possessions and the Torah scrolls, where, on the last possible day, they sail to join family in Naples; her father dies on the way. When they hear of cruelties being inflicted upon Jewish immigrants, the entire family leaves for Constantinople. “Can it be that at last we’ve arrived at a place where all kinds of people—Muslims, Christians, Jews—are allowed to live together side by side? And live peacefully?” (ARC 67)

In Part Two we meet Benvenida’s descendant Reina, who in 1923 longs for freedoms that are prohibited because she is a girl. When she attends a firework display celebrating Turkey’s independence with a male neighbor and sings to the other teens who are all boys, her father banishes her to Cuba to an aunt and an arranged marriage. “He has done what he needed to do. It has been very difficult for him.…he weeps for you as he has wept for the ancestors who fled Spain during the expulsion.” (ARC 97)

The story continues in 1963 in Fidel Castro’s Cuba with Reina’s youngest daughter Alegra who, along with her Muslim neighbor Teresita, volunteers to become a brigadista and teach people in the countryside to read and write. “I am so thankful for my freedom. And that I am able to fight for a cause I believe in.” (ARC 150) The family is politically divided, and people are leaving the country. Reina’s older children and their families leave for Israel and, after two weeks in jail, Alegra’s father brings her home and sends her to Miami, supported by the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. There she lives with foster parents for three years until her parents join her.

And last, in 2003 readers meet Alegra’s daughter Paloma, Sephardic-Cuban on mother’s side and Afro-Cuban on her father’s side. On a business trip the family visits Toledo and meets some surprising people, bringing the story full circle.

This is a story of history, prejudices and persecution, emigration, religion and Jewish tradition, freedoms, language, and four 12-year-old girls who come alive through poetry and song.

-----

“I feel like I carry a lot of history on my shoulders. Not only were my ancestors driven out of Spain, but my abuela had to leave Turkey, and my parents had to leave Cuba. So many seas were crossed.”—Paloma, 2003 (ARC 201)

There are numerous parts of history that we do not learn—or at least I didn’t learn until I visited foreign lands through travel and novels. There are many reasons why people emigrate to other lands—sometimes it is political; other times the catalyst is religious persecution; and sometimes the cause is being sent away by family members—and sometimes we cross the sea to discover our ancestral homeland. The characters in Ruth Behar’s new novel who travel across so many seas do so for many of these reasons.

The family saga begins in 1492 in Toledo formerly “known as the city of three cultures [where] Jews, Muslims, and Christians lived together peacefully for centuries.” (ARC 212). However, the Spanish Inquisition first persecuted the Muslims, turning mosques into cathedrals, and then the Jews who are threatened with the choice of conversion or hanging. Benvenida, her two brothers, and her parents are forced to leave Toledo and walk for days to the coast, carrying a few possessions and the Torah scrolls, where, on the last possible day, they sail to join family in Naples; her father dies on the way. When they hear of cruelties being inflicted upon Jewish immigrants, the entire family leaves for Constantinople. “Can it be that at last we’ve arrived at a place where all kinds of people—Muslims, Christians, Jews—are allowed to live together side by side? And live peacefully?” (ARC 67)

In Part Two we meet Benvenida’s descendant Reina, who in 1923 longs for freedoms that are prohibited because she is a girl. When she attends a firework display celebrating Turkey’s independence with a male neighbor and sings to the other teens who are all boys, her father banishes her to Cuba to an aunt and an arranged marriage. “He has done what he needed to do. It has been very difficult for him.…he weeps for you as he has wept for the ancestors who fled Spain during the expulsion.” (ARC 97)

The story continues in 1963 in Fidel Castro’s Cuba with Reina’s youngest daughter Alegra who, along with her Muslim neighbor Teresita, volunteers to become a brigadista and teach people in the countryside to read and write. “I am so thankful for my freedom. And that I am able to fight for a cause I believe in.” (ARC 150) The family is politically divided, and people are leaving the country. Reina’s older children and their families leave for Israel and, after two weeks in jail, Alegra’s father brings her home and sends her to Miami, supported by the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. There she lives with foster parents for three years until her parents join her.

And last, in 2003 readers meet Alegra’s daughter Paloma, Sephardic-Cuban on mother’s side and Afro-Cuban on her father’s side. On a business trip the family visits Toledo and meets some surprising people, bringing the story full circle.

This is a story of history, prejudices and persecution, emigration, religion and Jewish tradition, freedoms, language, and four 12-year-old girls who come alive through poetry and song.

-----

Allies by Alan Gratz

The Battle of Normandy, codenamed Operation Overlord, began on June 6, 1944, known as D-Day, when some 156,000 American, British and Canadian forces landed on five beaches along a 50-mile stretch of the heavily fortified coast of France’s Normandy region. The invasion was one of the largest amphibious military assaults in history and resulted in the Allied liberation of Western Europe from Nazi Germany’s control (www.History.com).

In Gratz’s new novel Allies, readers learn about the invasion on D-Day from multiple perspectives.

First, readers meet Dee Carpenter, a soldier from Philadelphia with a secret; his real name is Dietrich Zimmerman and he was born in Germany, his family having fled the Nazis. His best friend Sid is Jewish. Eleven-year-old Samira is French Algerian, and after her mother, a member of the French Resistance, is captured, she joins the Marquis (resistance codename) to find and free her mother. Unfortunately, as one of my favorite characters, she doesn’t reappear until the end of the book. James and his friend Sam, a Cree Indian, are members of the Canadian army, and Bill and Thomas are soldiers from England.

Readers last meet the black medic Henry who calms his patients by asking about their favorite movies and is faced with discrimination even as he saves lives. When he saves the white southern officer Lieutenant Hoyte, the man who had delivered discrimination with “the vilest of racial slurs,” and Hoyte says, “Thank you, corporal…You saved my life,” Henry thinks, “Maybe, just maybe, this was a beginning. Maybe serving together, fighting together, living and suffering together, would make white people see black people as equals.” (194)

Last, readers meet Dorothy, the American reporter disguised as a man so she can cover the battle, and the 13-year-old French Monique, who has an interest in first aid. Together they help save soldiers in the field, Monique soothing them with her singing.

As soldiers storm the beaches and parachute from airplanes, the fighting is described in great detail. “James had seen what happens when IF Day became WHEN Day. ‘Nobody should have to live like this, under the boot of Nazi rule, anywhere in the world,' James thought.” (132)

This novel would appeal to those who are interested in history, battles, artillery, and strategy. It would be a good choice for an author-study, historical-fiction book club, grouped with Gratz's Grenade, Refugee, Projeckt 1065, and Prisoner B-3087 in ELA or History/Social Studies classes.

-----

The Battle of Normandy, codenamed Operation Overlord, began on June 6, 1944, known as D-Day, when some 156,000 American, British and Canadian forces landed on five beaches along a 50-mile stretch of the heavily fortified coast of France’s Normandy region. The invasion was one of the largest amphibious military assaults in history and resulted in the Allied liberation of Western Europe from Nazi Germany’s control (www.History.com).

In Gratz’s new novel Allies, readers learn about the invasion on D-Day from multiple perspectives.

First, readers meet Dee Carpenter, a soldier from Philadelphia with a secret; his real name is Dietrich Zimmerman and he was born in Germany, his family having fled the Nazis. His best friend Sid is Jewish. Eleven-year-old Samira is French Algerian, and after her mother, a member of the French Resistance, is captured, she joins the Marquis (resistance codename) to find and free her mother. Unfortunately, as one of my favorite characters, she doesn’t reappear until the end of the book. James and his friend Sam, a Cree Indian, are members of the Canadian army, and Bill and Thomas are soldiers from England.

Readers last meet the black medic Henry who calms his patients by asking about their favorite movies and is faced with discrimination even as he saves lives. When he saves the white southern officer Lieutenant Hoyte, the man who had delivered discrimination with “the vilest of racial slurs,” and Hoyte says, “Thank you, corporal…You saved my life,” Henry thinks, “Maybe, just maybe, this was a beginning. Maybe serving together, fighting together, living and suffering together, would make white people see black people as equals.” (194)

Last, readers meet Dorothy, the American reporter disguised as a man so she can cover the battle, and the 13-year-old French Monique, who has an interest in first aid. Together they help save soldiers in the field, Monique soothing them with her singing.

As soldiers storm the beaches and parachute from airplanes, the fighting is described in great detail. “James had seen what happens when IF Day became WHEN Day. ‘Nobody should have to live like this, under the boot of Nazi rule, anywhere in the world,' James thought.” (132)

This novel would appeal to those who are interested in history, battles, artillery, and strategy. It would be a good choice for an author-study, historical-fiction book club, grouped with Gratz's Grenade, Refugee, Projeckt 1065, and Prisoner B-3087 in ELA or History/Social Studies classes.

-----

An Uninterrupted View of the Sky by Melanie Crowder

In a novel I read straight though, I again learned from Crowder, author of Audacity [see above]. An Uninterrupted View of the Sky takes place in Bolivia at the beginning of the 21st century and reveals how the United States’ role in the passage and enforcement of a law that violated the rights of citizens, especially the poor and indigenous peoples, led to innocent families living in prisons for years, hoping for the reform that has been slowly occurring. “Our lives are stretching out before us, unplanned and unpredictable” (p. 277).

Readers meet Francisco and his little sister Pilar and Francisco’s classmate and new friend Soledad, who become a part Bolivia’s prison children population. As they struggle to survive the violence of prison life and the streets and loss of family, they realize that education can help them make a change.

Suggestion: Pair with Deborah Ellis” I Am a Taxi, also about those who become caught in the Bolivian government’s war on drugs.

-----

In a novel I read straight though, I again learned from Crowder, author of Audacity [see above]. An Uninterrupted View of the Sky takes place in Bolivia at the beginning of the 21st century and reveals how the United States’ role in the passage and enforcement of a law that violated the rights of citizens, especially the poor and indigenous peoples, led to innocent families living in prisons for years, hoping for the reform that has been slowly occurring. “Our lives are stretching out before us, unplanned and unpredictable” (p. 277).

Readers meet Francisco and his little sister Pilar and Francisco’s classmate and new friend Soledad, who become a part Bolivia’s prison children population. As they struggle to survive the violence of prison life and the streets and loss of family, they realize that education can help them make a change.

Suggestion: Pair with Deborah Ellis” I Am a Taxi, also about those who become caught in the Bolivian government’s war on drugs.

-----

Audacity by Melanie Crowder

Audacity has become one of my all-time favorites historical novels and some of the best writing I have read. I usually choose books about more contemporary issues but am finding the same issues appearing throughout history, wearing different masks. Unfortunately oppression, intolerance, and treatment of refugees are not past, and we still need people unafraid to stand for their own rights and those of others.

Audacity relates the true story of Clara Lemlich, a Russian Jewish immigrant with dreams of an education who sacrifices everything to fight for better working conditions for women in the factories of Manhattan's Lower East Side in the early 1900's. Lyrically related in verse, the use of parallelism and the purposeful placement of the words is as effective as the words themselves.

The novel includes the history behind the story and a glossary of terms. What a wonderful "text" for a social studies class.

-----

Audacity has become one of my all-time favorites historical novels and some of the best writing I have read. I usually choose books about more contemporary issues but am finding the same issues appearing throughout history, wearing different masks. Unfortunately oppression, intolerance, and treatment of refugees are not past, and we still need people unafraid to stand for their own rights and those of others.

Audacity relates the true story of Clara Lemlich, a Russian Jewish immigrant with dreams of an education who sacrifices everything to fight for better working conditions for women in the factories of Manhattan's Lower East Side in the early 1900's. Lyrically related in verse, the use of parallelism and the purposeful placement of the words is as effective as the words themselves.

The novel includes the history behind the story and a glossary of terms. What a wonderful "text" for a social studies class.

-----

Everything Sad Is Untrue by Daniel Nayeri

Years ago I heard Tim O’Brien, author of The Things They Carried, tell an audience, “You don’t have to tell a true story to tell the truth.” When I facilitate memoir workshops, I advise writers that memoir is how the memoirist remembers and interprets events.

Everything Sad is Untrue is the story of Khosrou Nayeri on his way to becoming Daniel Nayeri. It is the stories of his childhood in Iran, in Dubai, in a refugee “camp” in Italy, in his relocation home in Oklahoma; it is also the stories of the Persian and Iranian people and history. It is a recounting that flits from time to time and person to person and place to place, inviting readers to participate as we form a relationship with the storyteller.

This is a collection of stories reminiscent of 1001 Arabian Nights. In fact, Daniel frequently compares himself to Scheherazade, telling readers, “Every story is the sound of a storyteller begging to stay alive.” (59) The author further explains that, in his case, “You don’t get to choose what you remember. A patchwork memory is the shame of a refugee.” (49) and later explains, “Memories are just stories we tell ourselves, after all. (349)

Everything Sad is Untrue reminds me of my favorite children’s book Haroun and the Sea of Stories in which Salman Rushdie proves “the use of stories that aren’t even true,” a novel that likewise blends Eastern and Western cultures.

But the most important feature of this wonderful novel is the author’s voice which comes through on every page. As our storyteller discloses, “The point of Nights is that if you spend time with each other—if we really listen in the parlors of our minds and look at each other as we were meant to be seen—then we would fall in love.…The stories aren’t the thing. The thing is the story of the story. The spending of the time. The falling in love.” (301) And that is why I am not recounting a summary of this story as in many of my reviews. I fell in love with the telling of the story.

A book certainly deserving its 2021 Michael L. Printz award, an award which annually honors the best book written for teens, based entirely on its literary merit.

-----

Years ago I heard Tim O’Brien, author of The Things They Carried, tell an audience, “You don’t have to tell a true story to tell the truth.” When I facilitate memoir workshops, I advise writers that memoir is how the memoirist remembers and interprets events.

Everything Sad is Untrue is the story of Khosrou Nayeri on his way to becoming Daniel Nayeri. It is the stories of his childhood in Iran, in Dubai, in a refugee “camp” in Italy, in his relocation home in Oklahoma; it is also the stories of the Persian and Iranian people and history. It is a recounting that flits from time to time and person to person and place to place, inviting readers to participate as we form a relationship with the storyteller.

This is a collection of stories reminiscent of 1001 Arabian Nights. In fact, Daniel frequently compares himself to Scheherazade, telling readers, “Every story is the sound of a storyteller begging to stay alive.” (59) The author further explains that, in his case, “You don’t get to choose what you remember. A patchwork memory is the shame of a refugee.” (49) and later explains, “Memories are just stories we tell ourselves, after all. (349)

Everything Sad is Untrue reminds me of my favorite children’s book Haroun and the Sea of Stories in which Salman Rushdie proves “the use of stories that aren’t even true,” a novel that likewise blends Eastern and Western cultures.

But the most important feature of this wonderful novel is the author’s voice which comes through on every page. As our storyteller discloses, “The point of Nights is that if you spend time with each other—if we really listen in the parlors of our minds and look at each other as we were meant to be seen—then we would fall in love.…The stories aren’t the thing. The thing is the story of the story. The spending of the time. The falling in love.” (301) And that is why I am not recounting a summary of this story as in many of my reviews. I fell in love with the telling of the story.

A book certainly deserving its 2021 Michael L. Printz award, an award which annually honors the best book written for teens, based entirely on its literary merit.

-----

Farewell Cuba, Mi Isla by Alexandra Diaz

“Look outside your window, children,” Mami said as they took their seats. “You may never see your country again.” (ARC, 36)

Victoria had a wonderful life in Cuba where she lived with her mother, father, and younger sister and brother. Also in the same duplex lived her cousin Jackie, her aunt, her uncle, and her baby cousin/godson. Even though they were very different and attended different schools in Havana, 12-year-old Victoria and Jackie were best friends, and they both spent time at their Papalfonso and Mamlara’s finca where Victoria rode her horse and swam with her cousin, a ranch that Victoria would inherit.

October 1960: With Fidel Castro in power and protestors arrested, news restricted, and professionals prohibited from leaving the country, Victoria’s family makes the decision to go to Miami, expecting their exile to “only last a few weeks, until the U.S. presidential election.” (14)

Alternating chapters focus on Victoria and Jackie and permit readers to learn what is happening in Cuba and about the Cuban community in Miami. Here Victoria lives in poverty (her father’s engineering degree of no use as he labors for minimum wage), and she tries to take charge of feeding her family. When Jackie arrives in Miami through the Peter Pan Project (reminiscent of the Holocaust Kindertransport), readers see how being apart from her immediate family affects her and her relationship with Victoria.

I often have read and reviewed novels (and memoirs) by Margarita Engle and noted that I learned quite a lot of Cuban history, a history missing from my education. Diaz’s novel, inspired by the experiences of her mother and family who came to the

United States from Cuba in 1960, spans October 1960 to June 1961 and teaches readers even more about Castro and his effect on Cuba and the Cuban citizens and the role the U.S. government played. This novel should be included in every American history course. This is also a story of prejudice, as experienced by Katya, Victoria’s Russian school friend, and of resilience and family. The Author’s Note further expands on the historical facts and includes a glossary of Cuban terms.

“Look outside your window, children,” Mami said as they took their seats. “You may never see your country again.” (ARC, 36)

Victoria had a wonderful life in Cuba where she lived with her mother, father, and younger sister and brother. Also in the same duplex lived her cousin Jackie, her aunt, her uncle, and her baby cousin/godson. Even though they were very different and attended different schools in Havana, 12-year-old Victoria and Jackie were best friends, and they both spent time at their Papalfonso and Mamlara’s finca where Victoria rode her horse and swam with her cousin, a ranch that Victoria would inherit.

October 1960: With Fidel Castro in power and protestors arrested, news restricted, and professionals prohibited from leaving the country, Victoria’s family makes the decision to go to Miami, expecting their exile to “only last a few weeks, until the U.S. presidential election.” (14)

Alternating chapters focus on Victoria and Jackie and permit readers to learn what is happening in Cuba and about the Cuban community in Miami. Here Victoria lives in poverty (her father’s engineering degree of no use as he labors for minimum wage), and she tries to take charge of feeding her family. When Jackie arrives in Miami through the Peter Pan Project (reminiscent of the Holocaust Kindertransport), readers see how being apart from her immediate family affects her and her relationship with Victoria.

I often have read and reviewed novels (and memoirs) by Margarita Engle and noted that I learned quite a lot of Cuban history, a history missing from my education. Diaz’s novel, inspired by the experiences of her mother and family who came to the

United States from Cuba in 1960, spans October 1960 to June 1961 and teaches readers even more about Castro and his effect on Cuba and the Cuban citizens and the role the U.S. government played. This novel should be included in every American history course. This is also a story of prejudice, as experienced by Katya, Victoria’s Russian school friend, and of resilience and family. The Author’s Note further expands on the historical facts and includes a glossary of Cuban terms.

Fast Pitch by Nic Stone

Twelve-year-old Shanice Lockwood is captain of a softball team, the Firebirds, the only all-Black softball team in the Dixie Youth Softball Association. She comes from a long line of batball players—her father, her grandfather PopPop, her great-grandfather. Her one goal is for her team to win the state championship.

But her goal shifts when she meets her Great-Great Uncle Jack, her Great-Grampy JonJon’s brother.

Shanice’s father had to quit baseball when he blew out his knee, his father had to stop playing to support his family, but why did JonJon quit when he was successfully playing for the Negro American League and was one of the first Black players recruited to the MLB? When Shanice is taken to Peachtree Hills Place to meet her sometimes-senile uncle, he tells her that JonJon “didn’t do what they said he did…He was framed.” (46) “My brother ain’t no thief. He didn’t do it…But I know who did.” (47)

And Shanice is off on a quest to research the incident that caused her great grandfather to leave baseball and to see if she, with Jack’s information and JonJon’s leather journal, can clear his name while still trying to lead her softball team to victory.

Fast Pitch is a fun new novel by Nic Stone, full of batball, adventure, a little mystery, peer and family relationships, Negro League history, prejudice, and maybe a first crush.

-----

Twelve-year-old Shanice Lockwood is captain of a softball team, the Firebirds, the only all-Black softball team in the Dixie Youth Softball Association. She comes from a long line of batball players—her father, her grandfather PopPop, her great-grandfather. Her one goal is for her team to win the state championship.

But her goal shifts when she meets her Great-Great Uncle Jack, her Great-Grampy JonJon’s brother.

Shanice’s father had to quit baseball when he blew out his knee, his father had to stop playing to support his family, but why did JonJon quit when he was successfully playing for the Negro American League and was one of the first Black players recruited to the MLB? When Shanice is taken to Peachtree Hills Place to meet her sometimes-senile uncle, he tells her that JonJon “didn’t do what they said he did…He was framed.” (46) “My brother ain’t no thief. He didn’t do it…But I know who did.” (47)

And Shanice is off on a quest to research the incident that caused her great grandfather to leave baseball and to see if she, with Jack’s information and JonJon’s leather journal, can clear his name while still trying to lead her softball team to victory.

Fast Pitch is a fun new novel by Nic Stone, full of batball, adventure, a little mystery, peer and family relationships, Negro League history, prejudice, and maybe a first crush.

-----

Flooded: Requiem for Johnstown by Ann E. Burg

On May 31, 1889, the South Fork Dam collapsed. Twenty million tons of water from Lake Conemaugh poured into Johnstown [Pennsylvania] and neighboring communities. More than 2,200 people died, including 99 entire families and 396 children. [Author’s Note] The flood still stands as the second or third deadliest day in U.S. history resulting from a natural calamity.

Richard Peck wrote, “The bigger the issue, the smaller you write.” And author Ann E. Burg

introduces readers to individual residents of the town.

We read the stories of fifteen-year-old Joe Dixon who wants to run his own newsstand and marry his Maggie; Gertrude Quinn who tells us about her brother, three sisters, Aunt Abbie, and her father who owns the general store. We come to know Daniel and Monica Fagan. Daniel’s friend Willy, the poet, encouraged by his teacher to write, and George with 3 brothers and 4 sisters who wants to leave school and help support them. We watch the town prepare for the Decoration Day ceremony honoring the war dead.

And after the flood, readers hear from Red Cross nurse Clara Barton, and Ann Jenkins and Nancy Little who brought law suits that found no justice, and a few of the 700 unidentified victims of the flood.

And there are the members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club—Andrew Carnegie, Charles J. Clarke, Henry Clay Frick, Andrew Mellon, Cyrus Elder, and Elias Unger, the wealthy of Pittsburgh who ignored repeated warnings that the dam holding their private lake needed to be repaired so it wouldn't give way. “They don’t care a whit about the likes of us.” (57)

This is a story of class and privilege and those who work tirelessly to make ends meet. As Monica says, “People who have money, who shop at fancy stores and buy pretty things, shouldn’t think they’re better than folks who scrabble and scrounge and go to sleep tired and hungry.” (111)

In free-verse narrative monologues, readers experience the lives of a town and its hard-working, family-oriented inhabitants—people we come to know and love, reluctant to turn the pages leading towards the disaster we know they will encounter. We bear witness to the events as we read and empathy for the plights of the people affected by those events.

This is a book that could be shared across middle grade and high school ELA, social studies, and science classes.

-----

On May 31, 1889, the South Fork Dam collapsed. Twenty million tons of water from Lake Conemaugh poured into Johnstown [Pennsylvania] and neighboring communities. More than 2,200 people died, including 99 entire families and 396 children. [Author’s Note] The flood still stands as the second or third deadliest day in U.S. history resulting from a natural calamity.

Richard Peck wrote, “The bigger the issue, the smaller you write.” And author Ann E. Burg

introduces readers to individual residents of the town.

We read the stories of fifteen-year-old Joe Dixon who wants to run his own newsstand and marry his Maggie; Gertrude Quinn who tells us about her brother, three sisters, Aunt Abbie, and her father who owns the general store. We come to know Daniel and Monica Fagan. Daniel’s friend Willy, the poet, encouraged by his teacher to write, and George with 3 brothers and 4 sisters who wants to leave school and help support them. We watch the town prepare for the Decoration Day ceremony honoring the war dead.

And after the flood, readers hear from Red Cross nurse Clara Barton, and Ann Jenkins and Nancy Little who brought law suits that found no justice, and a few of the 700 unidentified victims of the flood.

And there are the members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club—Andrew Carnegie, Charles J. Clarke, Henry Clay Frick, Andrew Mellon, Cyrus Elder, and Elias Unger, the wealthy of Pittsburgh who ignored repeated warnings that the dam holding their private lake needed to be repaired so it wouldn't give way. “They don’t care a whit about the likes of us.” (57)

This is a story of class and privilege and those who work tirelessly to make ends meet. As Monica says, “People who have money, who shop at fancy stores and buy pretty things, shouldn’t think they’re better than folks who scrabble and scrounge and go to sleep tired and hungry.” (111)

In free-verse narrative monologues, readers experience the lives of a town and its hard-working, family-oriented inhabitants—people we come to know and love, reluctant to turn the pages leading towards the disaster we know they will encounter. We bear witness to the events as we read and empathy for the plights of the people affected by those events.

This is a book that could be shared across middle grade and high school ELA, social studies, and science classes.

-----

Genesis Begins Again by Alicia D. Williams

“We’re gonna get evicted again. If we get evicted again, you said you’re gonna leave…. I’m tired of coming home and our stuff’s on the lawn waiting for crackheads to steal it. I’m tired of staying in people’s basements! Why can’t you just pay the rent! Just stop gambling and pay the rent!” (280)

Eighth-grader Genesis Anderson’s family has been evicted four times already. Her father has a gambling problem and is an alcoholic but somehow he moves them from Detroit to a house in the fashionable Farmington Hills. But again the rent is not paid, and they will probably lose this home also.

Genesis has other problem, problems with other kids at her schools calling her names based on the darkness of her skin. Her parents are from complicated families with ideas about skin color and class. Genesis hates the color of her skin and the texture of her hair, wishing she looked like her beautiful light-skinned mother. “’I can’t stand you, ‘ I say to my reflection.” (10) She thinks her father has rejected her because she is dark like he is. “What if I inherited all Dad’s ways? What if no one recognizes that I’m…one of the good ones?” (154) “Every single night I’ve prayed for God to make me beautiful—make me light. And every morning I wake up exactly the same.” (157)

Even though she is finally making friends in her new school, two friends—Todd and Sophia—who know what it’s like to be stereotyped and bullied and like Genesis for who she is, she tries to bleach her skin and relax her hair to fit in, become popular, and please her father and grandmother.

Through her chorus teacher’s discovery of her singing talent and introductions to the music of Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, and Eta James, Genesis finds the courage to audition for the school talent show and sing. “I can’t believe it. I did it. I, Genesis Anderson, stepped out onto that stage and sang. Out loud. In Public. Alone.” (249) At the actual performance, she discovers her strength. “I let each word soar. I swoop down to hug the little girl sitting on the curb with all her furniture. I visit the girl in the basement with the wrinkled brown bag passing from hand to hand. I kiss the lonely girl who hears ugly taunts from the mirror. I experience every moment. And I’m not afraid.” (348)

-----

“We’re gonna get evicted again. If we get evicted again, you said you’re gonna leave…. I’m tired of coming home and our stuff’s on the lawn waiting for crackheads to steal it. I’m tired of staying in people’s basements! Why can’t you just pay the rent! Just stop gambling and pay the rent!” (280)

Eighth-grader Genesis Anderson’s family has been evicted four times already. Her father has a gambling problem and is an alcoholic but somehow he moves them from Detroit to a house in the fashionable Farmington Hills. But again the rent is not paid, and they will probably lose this home also.

Genesis has other problem, problems with other kids at her schools calling her names based on the darkness of her skin. Her parents are from complicated families with ideas about skin color and class. Genesis hates the color of her skin and the texture of her hair, wishing she looked like her beautiful light-skinned mother. “’I can’t stand you, ‘ I say to my reflection.” (10) She thinks her father has rejected her because she is dark like he is. “What if I inherited all Dad’s ways? What if no one recognizes that I’m…one of the good ones?” (154) “Every single night I’ve prayed for God to make me beautiful—make me light. And every morning I wake up exactly the same.” (157)

Even though she is finally making friends in her new school, two friends—Todd and Sophia—who know what it’s like to be stereotyped and bullied and like Genesis for who she is, she tries to bleach her skin and relax her hair to fit in, become popular, and please her father and grandmother.

Through her chorus teacher’s discovery of her singing talent and introductions to the music of Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, and Eta James, Genesis finds the courage to audition for the school talent show and sing. “I can’t believe it. I did it. I, Genesis Anderson, stepped out onto that stage and sang. Out loud. In Public. Alone.” (249) At the actual performance, she discovers her strength. “I let each word soar. I swoop down to hug the little girl sitting on the curb with all her furniture. I visit the girl in the basement with the wrinkled brown bag passing from hand to hand. I kiss the lonely girl who hears ugly taunts from the mirror. I experience every moment. And I’m not afraid.” (348)

-----

Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhoads

Jerome, a black 12-year-old child who is bullied and has made his first friend was playing with a toy gun when a white policeman in a car shot him in the back and then offered no medical help. However, a 911 call misrepresented the 5’, 90-pound Jerome as a person with a gun, rather than a toy gun, and the policeman, against all evidence to the contrary, under oath swore, “I was in fear for my life.” And Jerome questions “when truth is a feeling, can it be both—true and untrue?” (132)

Jerome roams the world as a ghost, and when he and Officer Moore’s daughter Sarah become acquainted, he also meets the ghost of Emmett Till who shares his story. Jerome watches over this family and questions his new role —“Why haven’t I moved on?” (95), his relationship with Sarah, the relationships within Sarah’s family, and his relationships with the Ghost Boys, the hundreds of other black youth who have been killed. As he roams, he sees a Chicago filled with beauty and parks and flowers that was denied him as a child of color and poverty, and a recognition of injustice and tragedy is sparked. As Emmett says, “Someone decided they didn’t like us…. We were a threat, a danger. A menace.” (160) They are children.

I don’t advocate for employing many whole-class novels during the year, but this is a book that will generate important conversations about prejudice, discrimination, stereotyping, fear, and the historical span of racism in this country that need to be held. This novel also would be a valuable addition to a social studies class study of civil rights and social justice.

-----

Jerome, a black 12-year-old child who is bullied and has made his first friend was playing with a toy gun when a white policeman in a car shot him in the back and then offered no medical help. However, a 911 call misrepresented the 5’, 90-pound Jerome as a person with a gun, rather than a toy gun, and the policeman, against all evidence to the contrary, under oath swore, “I was in fear for my life.” And Jerome questions “when truth is a feeling, can it be both—true and untrue?” (132)

Jerome roams the world as a ghost, and when he and Officer Moore’s daughter Sarah become acquainted, he also meets the ghost of Emmett Till who shares his story. Jerome watches over this family and questions his new role —“Why haven’t I moved on?” (95), his relationship with Sarah, the relationships within Sarah’s family, and his relationships with the Ghost Boys, the hundreds of other black youth who have been killed. As he roams, he sees a Chicago filled with beauty and parks and flowers that was denied him as a child of color and poverty, and a recognition of injustice and tragedy is sparked. As Emmett says, “Someone decided they didn’t like us…. We were a threat, a danger. A menace.” (160) They are children.

I don’t advocate for employing many whole-class novels during the year, but this is a book that will generate important conversations about prejudice, discrimination, stereotyping, fear, and the historical span of racism in this country that need to be held. This novel also would be a valuable addition to a social studies class study of civil rights and social justice.

-----

Gringolandia by Lyn Miller-Lachmann

"The bigger the issue, the smaller you write."- Richard Price.

We read for many reasons but one essential purpose is to learn about our world, including its history, and to develop empathy for others. I found that, by teaching a social justice course through novels, my 8th graders learned about the effects of history on others, even others their age.

Lyn Miller-Lachmann's Gringolandia shares the story of high school student Daniel, a refugee from Chile's Pinochet regime, his activist "gringo" girlfriend Courtney, and Daniel's father who has just been released from years of torture in a Chilean prison and joins his family in Gringolandia.

Spanning 1980-1991 this novel would be a valuable addition to a Social Justice or History curriculum or in my personal case, a good read to learn a history generally not covered in curriculum.

-----

"The bigger the issue, the smaller you write."- Richard Price.

We read for many reasons but one essential purpose is to learn about our world, including its history, and to develop empathy for others. I found that, by teaching a social justice course through novels, my 8th graders learned about the effects of history on others, even others their age.

Lyn Miller-Lachmann's Gringolandia shares the story of high school student Daniel, a refugee from Chile's Pinochet regime, his activist "gringo" girlfriend Courtney, and Daniel's father who has just been released from years of torture in a Chilean prison and joins his family in Gringolandia.

Spanning 1980-1991 this novel would be a valuable addition to a Social Justice or History curriculum or in my personal case, a good read to learn a history generally not covered in curriculum.

-----

How I Became a Spy: A Mystery of WWII London by Deborah Hopkinson

Mystery, spies, double agents, coded messages, a heroic dog, and WWII! How I Became A Spy takes place between February 18 and March 1, 1944, a time period which affected the successful invasion held on D-Day.

Bertie is a 13-year-old who lives in a London experiencing the Little Blitz attacks. Feeling guilt over his older brother’s serious injuries from the Blitz a few years before, Bertie lives in the police barracks with his father and serves as a civil defense volunteer with Little Roo, his dog trained to rescue people from bombed buildings.

During one nighttime raid, he meets a mysterious American girl, finds a notebook, discovers a young woman who is passed out on a street (disappearing by the time he brings back help), and he becomes involved in a mystery of intrigue. As he reads through the notebook, which belongs to a female French spy being trained by the Special Operations Executive, he finds that it contains coded messages that he needs to crack to save the woman and the secrecy of the planned invasion of Occupied France. Bertie joins forces with Eleanor, the American girl who was holding the notebook for her former French tutor and friend, and his best friend and classmate David, a Jewish refugee from Germany, who is well-versed in ciphers.

With only a few days until the trap is to be set for the double agent, the three have to determine whom to trust as they work to break the ciphers and put Violette’s plan in motion.

David encourages them, “Sometimes people do the impossible…look at me, and others who came here on trains. Thousands of us are here, and alive, only because a few people did what others thought couldn’t be done.” (179-180)

With references to Sherlock Holmes and quotes from the actual Special Operations Executive training lecture and manual, as well as practice cipher messages, this novel is a fun and exciting read through history with memorable characters, some of whom actually existed.

As the boys’ history teacher says, “…because we are living through a war against tyranny, we have a special responsibility…To learn from the past, understand the present, and change the future.” (191)

-----

Mystery, spies, double agents, coded messages, a heroic dog, and WWII! How I Became A Spy takes place between February 18 and March 1, 1944, a time period which affected the successful invasion held on D-Day.

Bertie is a 13-year-old who lives in a London experiencing the Little Blitz attacks. Feeling guilt over his older brother’s serious injuries from the Blitz a few years before, Bertie lives in the police barracks with his father and serves as a civil defense volunteer with Little Roo, his dog trained to rescue people from bombed buildings.

During one nighttime raid, he meets a mysterious American girl, finds a notebook, discovers a young woman who is passed out on a street (disappearing by the time he brings back help), and he becomes involved in a mystery of intrigue. As he reads through the notebook, which belongs to a female French spy being trained by the Special Operations Executive, he finds that it contains coded messages that he needs to crack to save the woman and the secrecy of the planned invasion of Occupied France. Bertie joins forces with Eleanor, the American girl who was holding the notebook for her former French tutor and friend, and his best friend and classmate David, a Jewish refugee from Germany, who is well-versed in ciphers.

With only a few days until the trap is to be set for the double agent, the three have to determine whom to trust as they work to break the ciphers and put Violette’s plan in motion.

David encourages them, “Sometimes people do the impossible…look at me, and others who came here on trains. Thousands of us are here, and alive, only because a few people did what others thought couldn’t be done.” (179-180)

With references to Sherlock Holmes and quotes from the actual Special Operations Executive training lecture and manual, as well as practice cipher messages, this novel is a fun and exciting read through history with memorable characters, some of whom actually existed.

As the boys’ history teacher says, “…because we are living through a war against tyranny, we have a special responsibility…To learn from the past, understand the present, and change the future.” (191)

-----

I Can Make This Promise by Christine Day

“I think about Roger. He was the first person to ever say those words to me. ‘You look Native.’ And it didn’t feel presumptuous. It didn’t feel like a wild guess. It was like he recognized me. Like he saw something in me.” (24)

Twelve-year-old Edie Green knows she is half Native American and that her mother was adopted and raised by a white couple at a very young age. But that is all she knows about her heritage, and she has never thought to ask for whom she is named. She discovered that she was “different” on the first day of kindergarten, a day she remembers in great detail, a day when her teacher’s questions about “where she was from” panicked her. But this was something she and her mother never discussed.

The summer before seventh grade, Edie and her friends discover a box in her attic, a box with pictures and letter from a young woman named Edith who looks just like Edie. When she asks her mother about her name, her mother lies, and a few days later they have a fight when Edie wants to see a movie featuring a Native American character. Now Edie doesn’t know how her mother will react when she tells her she has found the box and has read Edith Graham’s letters. Even her mother’s older brother, Uncle Phil, won’t tell her the secret.

When Edie’s mother finally shares her past and the past of her birth family, “I didn’t picture this. I wasn’t ready for this horrific injustice.” (230)

I Can Make This Promise shares a time of intolerance and injustice in U.S. history, a time before the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 became a vital piece of legislation.

-----

“I think about Roger. He was the first person to ever say those words to me. ‘You look Native.’ And it didn’t feel presumptuous. It didn’t feel like a wild guess. It was like he recognized me. Like he saw something in me.” (24)

Twelve-year-old Edie Green knows she is half Native American and that her mother was adopted and raised by a white couple at a very young age. But that is all she knows about her heritage, and she has never thought to ask for whom she is named. She discovered that she was “different” on the first day of kindergarten, a day she remembers in great detail, a day when her teacher’s questions about “where she was from” panicked her. But this was something she and her mother never discussed.

The summer before seventh grade, Edie and her friends discover a box in her attic, a box with pictures and letter from a young woman named Edith who looks just like Edie. When she asks her mother about her name, her mother lies, and a few days later they have a fight when Edie wants to see a movie featuring a Native American character. Now Edie doesn’t know how her mother will react when she tells her she has found the box and has read Edith Graham’s letters. Even her mother’s older brother, Uncle Phil, won’t tell her the secret.

When Edie’s mother finally shares her past and the past of her birth family, “I didn’t picture this. I wasn’t ready for this horrific injustice.” (230)

I Can Make This Promise shares a time of intolerance and injustice in U.S. history, a time before the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 became a vital piece of legislation.

-----

Iceberg by Jenniefer A. Nielsen

“So I’d begun to work hard and to sacrifice what I wanted for what my family needed. I’d learned to be bold and to take risks when necessary. That’s what had kept my family going for the past two years. It’s how I would help them now.” (45)

Many of us know, or think we know, a lot about the Titanic, but Jennifer Nielsen lets us travel on the Titanic and learn about the tragedy through the eyes of twelve-year-old future journalist Hazel Rothbury, a stowaway third-class passenger. Hers is one story out of 2,224; one survivor out of 705.

Hazel didn’t mean to stow away. After her father’s death at sea, her mother was sending her to America to work in a factory with her aunt to support, and save, the family at home. When the money she had was not enough for a ticket, Hazel stows away, eventually with the help of Charlie Blight, a young porter also supporting his family. Hazel is also befriended by Sylvia, a girl in first class, much to the consternation of Sylvia’s governess.

Hazel had done her research on the Titanic, but when she overhears that there is a fire on the ship, she realizes how little she—and the other passengers—actually know and her questions grow. As she illicitly traverses the ship, talking with crew and passengers, she fills her notebook with questions and answers, hoping to sell a story when she arrives in New York and become a journalist rather than a factory worker. Her questions, and her doubts about the safety of the unsinkable Titanic, grow as she leans about single and double hulls, coal fires, the different types of icebergs and how they are discerned, Morse Code, and, most important, refraction.

In the midst of all this, Hazel becomes embroiled in a mystery. Is there a devious plot that will harm her new friend Sylvia? Her new, older friend Mrs. Abelman? Just who are the villains, what are they up to, and why do they wish her harm.

Readers learn much more about the Titanic, the passengers, their activities, the on-board class system—and the tragedy that sent 2/3 of the passengers and crews to their deaths and the heroes that helped 1/3 to survive. They learn such eye-opening facts that while the Titanic could have carried 64 lifeboats., it only carried 20, 18 of which were launched with passengers but with 472 empty seats. (299)

This is a novel for cross-curricular study: English-Language Arts, Mathematics, Social Studies, and Science, while the mystery will engage reluctant readers.

-----

“So I’d begun to work hard and to sacrifice what I wanted for what my family needed. I’d learned to be bold and to take risks when necessary. That’s what had kept my family going for the past two years. It’s how I would help them now.” (45)

Many of us know, or think we know, a lot about the Titanic, but Jennifer Nielsen lets us travel on the Titanic and learn about the tragedy through the eyes of twelve-year-old future journalist Hazel Rothbury, a stowaway third-class passenger. Hers is one story out of 2,224; one survivor out of 705.

Hazel didn’t mean to stow away. After her father’s death at sea, her mother was sending her to America to work in a factory with her aunt to support, and save, the family at home. When the money she had was not enough for a ticket, Hazel stows away, eventually with the help of Charlie Blight, a young porter also supporting his family. Hazel is also befriended by Sylvia, a girl in first class, much to the consternation of Sylvia’s governess.

Hazel had done her research on the Titanic, but when she overhears that there is a fire on the ship, she realizes how little she—and the other passengers—actually know and her questions grow. As she illicitly traverses the ship, talking with crew and passengers, she fills her notebook with questions and answers, hoping to sell a story when she arrives in New York and become a journalist rather than a factory worker. Her questions, and her doubts about the safety of the unsinkable Titanic, grow as she leans about single and double hulls, coal fires, the different types of icebergs and how they are discerned, Morse Code, and, most important, refraction.

In the midst of all this, Hazel becomes embroiled in a mystery. Is there a devious plot that will harm her new friend Sylvia? Her new, older friend Mrs. Abelman? Just who are the villains, what are they up to, and why do they wish her harm.

Readers learn much more about the Titanic, the passengers, their activities, the on-board class system—and the tragedy that sent 2/3 of the passengers and crews to their deaths and the heroes that helped 1/3 to survive. They learn such eye-opening facts that while the Titanic could have carried 64 lifeboats., it only carried 20, 18 of which were launched with passengers but with 472 empty seats. (299)

This is a novel for cross-curricular study: English-Language Arts, Mathematics, Social Studies, and Science, while the mystery will engage reluctant readers.

-----

It Doesn't Take a Genius by Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich

“I don’t even like debate, to be honest. But I’m good at it, and I learned early on that’s what matters. People love a winner. When you win, everyone sees you. And if people don’t see you, maybe you’re not really there.” (8)

Thirteen-year-old Emmett Charles is a winner, or at least at his school where his vocabulary, three debate trophies, science fair award, and Spelling Bee record have him feeling he might even be a genius.

And when his social skills and small size fail him, his older brother Luke is always there to bail him out , especially with Mac, his bully. “Luke has come out of nowhere. Like a superhero. He’s even taller than Mac, wears his shirts a little small so girls can peep his muscles, and his fade is tight and gleaming.” (6-7) “Sometimes it feels like I’m in a river, and the current’s real strong. And I have a choice between clinging to a rock and getting left behind, or letting myself get swept up in it and carried along without any control. Luke’s my rock.” (138)

But when his brother Luke gets a scholarship to a private art school in Maine for his last year of high school, summer is all Emmett, or E as he wants to be called, will have for Luke to turn him back into a winner after he passed on competing in this year’s debate championship. “We’re a team. Batman and Robin.” (29)

But when he discovers that Luke has gotten a job as a junior counselor at Camp DuBois, a historic Black summer camp in New York, and Emmett schemes to get himself a scholarship to attend as a camper. When he arrives he discovers that

“What my friends, and my family for that matter, don’t seem to understand is that I don’t swim. I guess they get the fact that I can’t. But they keep thinking that I will, one day. That I even want to. And they’re WRONG. Dad was supposed to teach me, and he’s not here.” (19) Emmett’s father died when he was 5, and Like and his mother don’t discuss his father with him which saddens him. In fact, seeing other kids with their dads sadden him.

And most important he discovers, as Natasha says, “It doesn’t take a genius to be a friend.” (291)

E’s story is filled with great characters: the socially-awkward Charles who can “do you” the best I have seen; Charles’ love interest and budding playwright Michelle, Emmett’s crush Natasha who does win at everything but is just as happy when the camp director decides there will be no final competitions; the alleged-bully Derek who is able to spend more time with Luke than Emmett does, but, as is often the case, is more complex than presumed; and the assortment of other campers, counselors, and group leaders. Readers will learn not only a lot of Black history but the importance of studying one’s cultural roots.

There will be adolescents in the classroom and community who need to read this book. I know that I learned quite a lot which led me to want to know more‑about Black culture and my culture and the cultures of others.

-----

“I don’t even like debate, to be honest. But I’m good at it, and I learned early on that’s what matters. People love a winner. When you win, everyone sees you. And if people don’t see you, maybe you’re not really there.” (8)

Thirteen-year-old Emmett Charles is a winner, or at least at his school where his vocabulary, three debate trophies, science fair award, and Spelling Bee record have him feeling he might even be a genius.

And when his social skills and small size fail him, his older brother Luke is always there to bail him out , especially with Mac, his bully. “Luke has come out of nowhere. Like a superhero. He’s even taller than Mac, wears his shirts a little small so girls can peep his muscles, and his fade is tight and gleaming.” (6-7) “Sometimes it feels like I’m in a river, and the current’s real strong. And I have a choice between clinging to a rock and getting left behind, or letting myself get swept up in it and carried along without any control. Luke’s my rock.” (138)

But when his brother Luke gets a scholarship to a private art school in Maine for his last year of high school, summer is all Emmett, or E as he wants to be called, will have for Luke to turn him back into a winner after he passed on competing in this year’s debate championship. “We’re a team. Batman and Robin.” (29)

But when he discovers that Luke has gotten a job as a junior counselor at Camp DuBois, a historic Black summer camp in New York, and Emmett schemes to get himself a scholarship to attend as a camper. When he arrives he discovers that

- His brother will be too busy to spend any time with him

- The camp is filled with “geniuses” and nerds—and new friends who have his back

- He will be discovering more of his culture and history through classes like “Black to the Future” and the camp focuses on community, not individual success. He finally realizes that “DuBois is preparing me for something more than bubble tests, more than I’d ever thought it would.” (190)

- Even though he is a great dancer, he is an even better choreographer

- Although he sees himself as a winner, without effort and spreading himself too thin, he can lose, more than he thought

- He will have to take swimming lessons (with the Littles) and pass a swimming test

“What my friends, and my family for that matter, don’t seem to understand is that I don’t swim. I guess they get the fact that I can’t. But they keep thinking that I will, one day. That I even want to. And they’re WRONG. Dad was supposed to teach me, and he’s not here.” (19) Emmett’s father died when he was 5, and Like and his mother don’t discuss his father with him which saddens him. In fact, seeing other kids with their dads sadden him.

And most important he discovers, as Natasha says, “It doesn’t take a genius to be a friend.” (291)

E’s story is filled with great characters: the socially-awkward Charles who can “do you” the best I have seen; Charles’ love interest and budding playwright Michelle, Emmett’s crush Natasha who does win at everything but is just as happy when the camp director decides there will be no final competitions; the alleged-bully Derek who is able to spend more time with Luke than Emmett does, but, as is often the case, is more complex than presumed; and the assortment of other campers, counselors, and group leaders. Readers will learn not only a lot of Black history but the importance of studying one’s cultural roots.

There will be adolescents in the classroom and community who need to read this book. I know that I learned quite a lot which led me to want to know more‑about Black culture and my culture and the cultures of others.

-----

Kaleidoscope Eyes by Jen F. Bryant

This Jen Bryant novel in verse is yet another opportunity for readers to learn history through story, discovering patterns the pieces make.

“I lie down on my bed,

Point my kaleidoscope at the ceiling light,

Watch the patterns scatter, the pieces

Slide apart and come back together

In ways I hadn’t noticed before.” (149)

The time period of the novel is 1966-1968, but eighth-grader Lyza’s life is also affected by the years before.

She is affected by the “Unwritten Rules” that govern her close friendship with Malcolm Dupree—from tricycle days until now, they have “gotten along like peas in a pod.” (11) But it is a friendship that causes Lyza to experience the prejudice of the times and her town. “We sure didn’t make the rules / about who can be friends with whom / and we don’t like the rules the way they are…/ but we are also not fools… And so—/ in the halls, at lunch, and in class / Malcolm stays with the other black kids / and I stay with the other white kids…” (12) And when they meet new people and go to new places, they are wary and watchful in a way adolescents should not need to be.

Her every action is affected by her mother’s leaving two years before when Lyza was in sixth grade and “when our family began to unravel” (5). Her college professor father works all hours, taking on extra classes and leaving Kyza and Denise to their own devices and discipline. Denise gives up college and her dreams of becoming a doctor to work in the local diner and hang out with her hippie boyfriend, Harry.

The town is affected by war in Vietnam which causes Lyza to don her black funeral dress too many times, and “Not coming back” attains a new meaning. So much so, Lyza realizes that her mother is probably never coming back either. And when Malcolm’s brother Dixon is drafted and sent to Vietnam, feelings of helplessness overwhelm her,

“When someone you love

leaves,

and there is

nothing nothing nothing

you can do about it, not one thing

you can say to

stop that person whom you love

so much

from going away, and you know that today

may just be

the very last time you will ever

see them hear them hold them,

when that day comes, there is not much

you can do,

not much you can say.” (120)

Lyza’s grandfather dies and leaves her a mystery tied to pirate Captain Kidd, maps—old and current, a key, and a drawer, file, and documents numbers for the Historical Society of Brigantine. Lyza, Malcolm, and Carolann (“…whenever I am with Carolann and Malcolm at the same time…that’s when I feel almost normal.”) (15) spend the summer working out the mystery with the help of, surprisingly, Denise, and even more unexpectedly, Harry, Denise’s “strong, long-haired boyfriend” who is smarter, more resourceful, and more trustworthy than Lyza presumed.

It is a summer of spyglasses and kaleidoscopes, letting go, realization that “…my family might be messed up but my friends [a widening circle] are as steady as they come.” (214) A summer that is important to Lyza, her family, and the town.

“I take my kaleidoscope off the shelf…

I turn and turn and turn and turn,

Letting the crystals shift into strange

And beautiful patterns, letting the pieces fall

Wherever they will.” (257)

-----

This Jen Bryant novel in verse is yet another opportunity for readers to learn history through story, discovering patterns the pieces make.

“I lie down on my bed,

Point my kaleidoscope at the ceiling light,

Watch the patterns scatter, the pieces

Slide apart and come back together

In ways I hadn’t noticed before.” (149)

The time period of the novel is 1966-1968, but eighth-grader Lyza’s life is also affected by the years before.

She is affected by the “Unwritten Rules” that govern her close friendship with Malcolm Dupree—from tricycle days until now, they have “gotten along like peas in a pod.” (11) But it is a friendship that causes Lyza to experience the prejudice of the times and her town. “We sure didn’t make the rules / about who can be friends with whom / and we don’t like the rules the way they are…/ but we are also not fools… And so—/ in the halls, at lunch, and in class / Malcolm stays with the other black kids / and I stay with the other white kids…” (12) And when they meet new people and go to new places, they are wary and watchful in a way adolescents should not need to be.