- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

- Asian, Asian-American

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

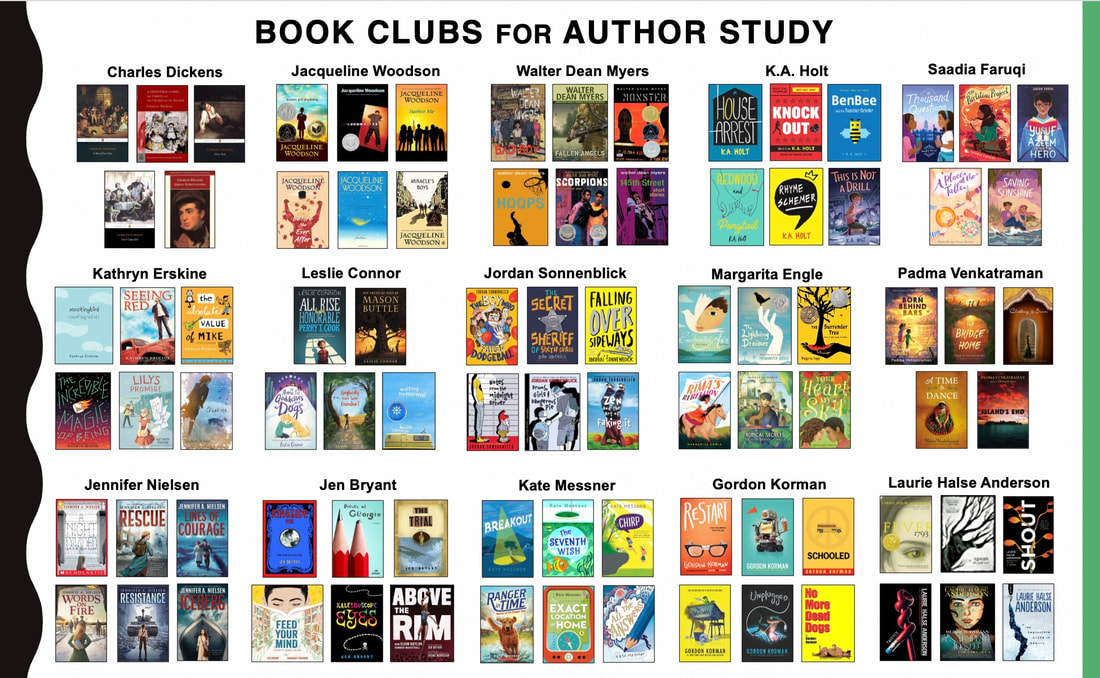

20. AUTHOR STUDY BOOK CLUBS

An Author Study gives readers the opportunity to delve deeply into an author’s life and body of work.

Alternative, especially for a more advanced class, each Book Club can read a different author and their works:

An Author Study is most effective when Book Clubs choose authors who write in a variety of genres and even writing styles (prose, verse, graphic) or formats and create a variety of characters.

In addition to reading several works by an author, key components of an Author Study include discussion, research, and a final project to present to the class.

Book Club members:

1. Make connections between the author’s life and work.

2. Make connections among the author's writings.

3. Make personal connections between their own experiences and those of the author and his/her characters.

Author Study Book Clubs offer all the advantages of Book Club reading and discussions

• social

• supportive

• deeper discussions in safe spaces

• collaboration

• increased reading and employment of skills

• motivation (and peer pressure) to read

• meet listening and speaking standards

• differentiation

• choice

as well as the added advantage of reading-like-a-writer.

The texts shown are upper elementary, middle grade, and Young Adult, but Author Study Book Clubs can be held in younger grades with authors such as Kate DiCamillo, Patrica Polacco, etc. (I am more familiar with authors and books for grades 4-12).

Ideas for employing Author Study Book Clubs, as well as many other Text Club options, are included in Talking Texts: A Teachers' Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum.

For strategies and ideas for setting up Book Clubs, see my blog "The 5 Steps of Facilitating Book Clubs."

- The class together

- researches the author and

- reads one of the author’s works (possibly their memoir) as a Whole-Class text and

- discusses the author's writing style and anything else they notice—HOW the author writes and WHAT they write.

- Next, each Book Club reads a different novel/text written by the author.

- During Book Club meetings, readers focus on writing, characters, and plots.

- One member from each Book Club could meet in an Inter-Book Club meeting to compare/contrast their authors and group novel/memoir with that of the other Book Clubs.

- Each Book Club prepares a presentation on the book they read for the rest of the class.

- The entire class compares/contrasts the author's works—writing style, characters, plots.

Alternative, especially for a more advanced class, each Book Club can read a different author and their works:

- Book Club members together research the author and read one of the author’s works (possibly their memoir) and discuss their writing style and anything else they notice—HOW they write and WHAT they write.

- Then each member reads a different novel written by the author. In some cases two Book Club members might read the same novel for support.

- During group meetings readers in each Book Club compare/contrast the author's works, writing, characters, and plots.

- Each Book Club prepares a presentation on the author and the books they read for the rest of the class.

- The entire class compares/contrasts the 5-6 authors' works—writing style, characters, plot

- This type of Book Club allows for reading diverse authors (and characters), genres, and formats.

- The mentor text to which readers can first discuss writers' craft and compare/contrast is the Whole-Class novel the class previously read.

An Author Study is most effective when Book Clubs choose authors who write in a variety of genres and even writing styles (prose, verse, graphic) or formats and create a variety of characters.

- Walter Dean Myers is the perfect example: He wrote memoir, sports fiction, historical fiction, street-life fiction, romance, short story collections, and even picture books for ESL readers; his novel Monster has been republished as a graphic novel.

- Another example is Jacqueline Woodson who writes for all ages and reading levels—picture books, upper elementary, middle grades, and YA (and adult)—in prose and verse. For example, for a Jacqueline Woodson Study (a good choice because she writes both male and female main characters), the class could read her memoir Brown Girl Dreaming and then readers could choose one of her other books to form their Book Clubs. If time didn't allow for two novels, the class could first read and discuss some of Woodson's picture books and then note how she employs the same or different writing strategies in the novels they are reading in Book Clubs.

- The author and texts pictured are examples.

In addition to reading several works by an author, key components of an Author Study include discussion, research, and a final project to present to the class.

Book Club members:

1. Make connections between the author’s life and work.

2. Make connections among the author's writings.

3. Make personal connections between their own experiences and those of the author and his/her characters.

Author Study Book Clubs offer all the advantages of Book Club reading and discussions

• social

• supportive

• deeper discussions in safe spaces

• collaboration

• increased reading and employment of skills

• motivation (and peer pressure) to read

• meet listening and speaking standards

• differentiation

• choice

as well as the added advantage of reading-like-a-writer.

The texts shown are upper elementary, middle grade, and Young Adult, but Author Study Book Clubs can be held in younger grades with authors such as Kate DiCamillo, Patrica Polacco, etc. (I am more familiar with authors and books for grades 4-12).

Ideas for employing Author Study Book Clubs, as well as many other Text Club options, are included in Talking Texts: A Teachers' Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum.

For strategies and ideas for setting up Book Clubs, see my blog "The 5 Steps of Facilitating Book Clubs."

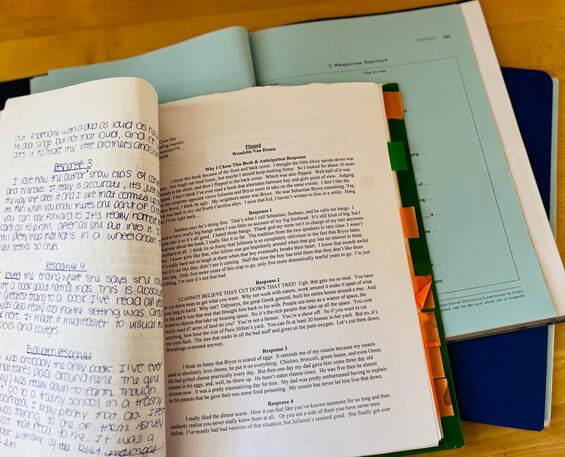

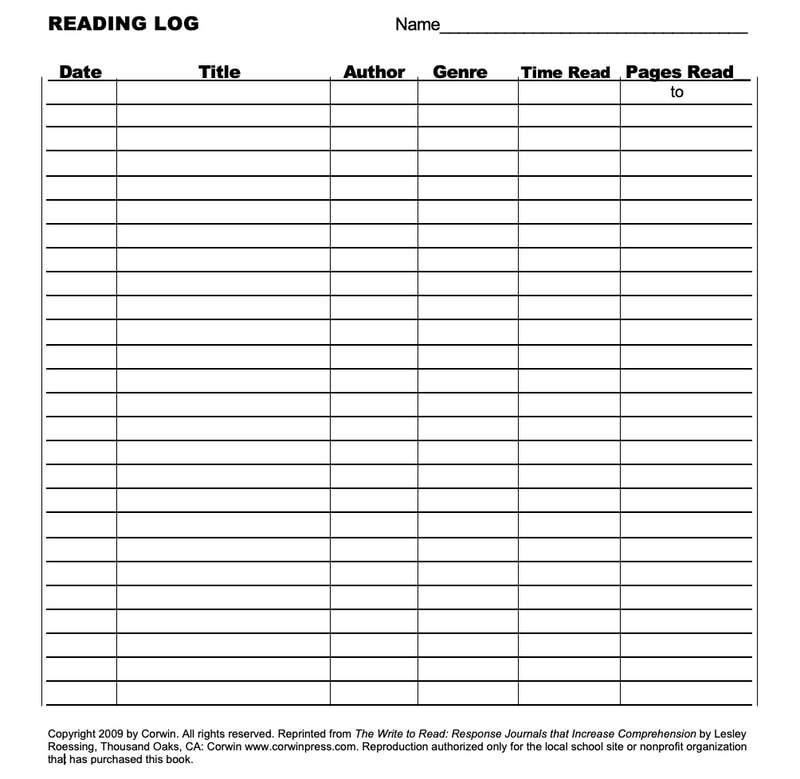

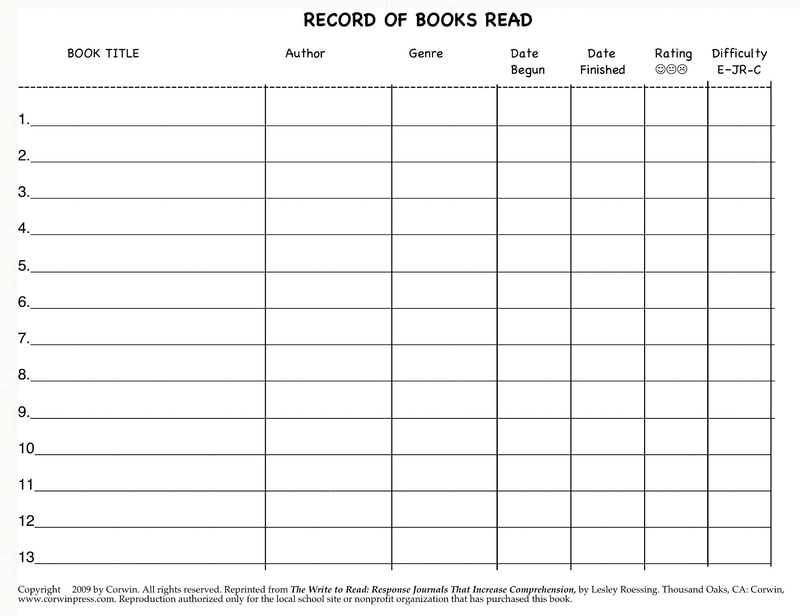

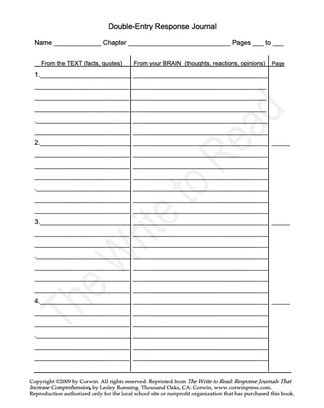

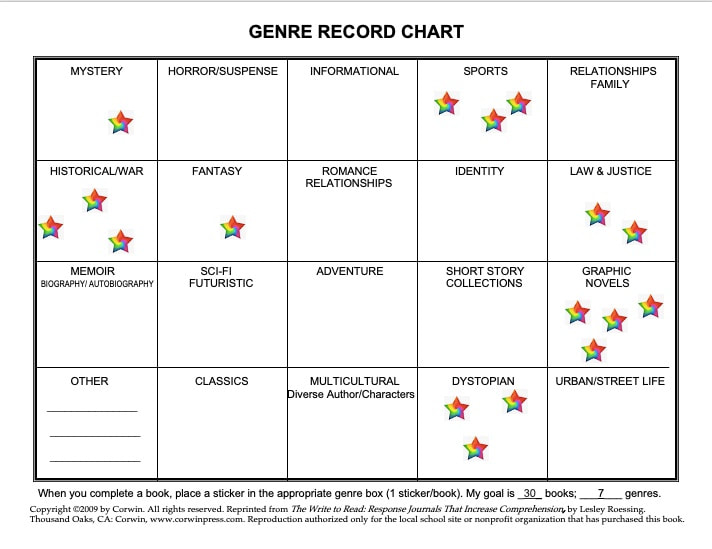

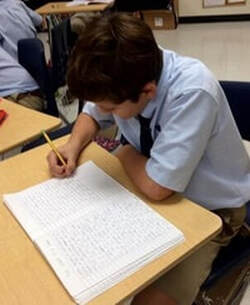

19. READING JOURNALS

Authentic reading is interactive. In order for students to learn, understand, and remember information, they must act on it. Journaling is a way of manipulating, exploring, challenging, and storing information. Reader Response focuses on the reader’s personal interaction with the text and focuses on using RESPONSE JOURNALS to increase comprehension.

Each student has a two-pocket Duo-tang folder with 3 prong fasteners; I have been lucky to find these at Staples in July for a penny each, but they can be added to student supply lists. I advise students that they may want to purchase vinyl folders which last all year instead; the paper journals will probably need to be replaced during the year.

Journals included

- My Independent Reading Requirements, signed by student and guardian

- Daily Reading Log – to fill out so they can look back and analyze their reading habits (something we did once a marking period). Student can use ditto marks instead of rewriting titles each day. Sometimes they will be reading magazines or newspapers rather than their self-selected novel. I tell readers that even though they are supposed to read for 25 minutes, if they read more or less to write the actual time so they can track their reading habits. No guardian signatures required. Students were only required to read and respond to one text—whole-class, book club, or independent self-selected—at a time. (See "Losing the Fear of Sharing Control: Starting a Reading Workshop")

- An 8.5” x 11” cardstock Books-Read Record – readers can record when they start and finish a book and rate the book and the reading challenge. When they fill up one side, I give them 2-sided Books-Read Records on regular plain paper. The cardstock was used for the first one for the Genre Chart on the flip side of the original page.*

- *Genre Chart on the reverse side of the Books Read Record page 1– to track genre choices and diversity [see Reading Strategy #5]

- composition paper – 5 days (in Reading Workshop) or nights (on Writing Workshop days) per week students were to read for approximately 25 minutes and write a 5-minute response in their Journals. If they were absent or were reading at home and did not have their Journal, they could simply write on composition paper and add upon return to school

- Students add any handouts, such as the Reader Response forms (double entry, sticky-note responses, drawing through the text responses, etc.) that they learn to use rather than the free-writing responses. [See some examples in the blog “The Importance of Reader Response” and “The Benefits of After-Reading Response”]

- Journals also include other handouts, such as my "Response Starters" list and forms where they can write words that are new to them and forms for jotting down future reads from Book Passes and listening to their classmates' book talks, etc.**

I collected the Journals from each class on a different day of the week and spent about 45-50 minutes reading through the class. I told my readers that, in case I did not have a chance to read all their entries, to put an asterisk next to the entry that they really wanted me to read, and maybe to respond to, but I enjoyed them so much that I usually read them all.

Students earned 20 points for each 5-minute entry (expected length and depth were based on their proficiencies); at times I gave them a particular “assignment” based on our focus lesson for that week: “In one of your journalings this week, discuss your main character’s personality traits—and jot CT in the margin of that entry.” If they had 5 entries, but none addressed Character Traits, they earned 90 points, rather than the full 100. I gave no quizzes or exams for reading grades; students' grades were based on points earned from their weekly journals and small projects for book club and independent readings, such as those discussed in "The Benefits of After-Reading Response," and which let me see how readers applied concepts taught through the daily Reading Workshop Focus Lessons.

Reader Response journals led to all students increasing their comprehension of texts by promoting interaction with the text. Read about "The Importance of Reader Response" and "The Benefits of After-Reading Response."

**All ideas, strategies, and forms are from The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension.

Below is a sample of the many different reproducible reader response journal forms included in The Write to Read (as well as the forms shown above):

Students earned 20 points for each 5-minute entry (expected length and depth were based on their proficiencies); at times I gave them a particular “assignment” based on our focus lesson for that week: “In one of your journalings this week, discuss your main character’s personality traits—and jot CT in the margin of that entry.” If they had 5 entries, but none addressed Character Traits, they earned 90 points, rather than the full 100. I gave no quizzes or exams for reading grades; students' grades were based on points earned from their weekly journals and small projects for book club and independent readings, such as those discussed in "The Benefits of After-Reading Response," and which let me see how readers applied concepts taught through the daily Reading Workshop Focus Lessons.

Reader Response journals led to all students increasing their comprehension of texts by promoting interaction with the text. Read about "The Importance of Reader Response" and "The Benefits of After-Reading Response."

**All ideas, strategies, and forms are from The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension.

Below is a sample of the many different reproducible reader response journal forms included in The Write to Read (as well as the forms shown above):

18. TEACHER READ-ALOUDS

I am a huge proponent of reading aloud to students – of all ages— for three reasons:

However, I see posts from teachers who are reading aloud all the novels they are “teaching,” or rather, novels through which they are teaching reading strategies and meeting standards.

In my classroom and those I have visited, I read aloud every day, but I read aloud the short mentor texts used for my Reading and Writing Workshop Focus Lessons—poems, picture books, short stories, news articles, and excerpts.

When reading aloud entire novels, there are some problems:

STRATEGY: Read aloud a short text, or passage, every day as part of the Workshop mini-lesson. [See my sample Reading Workshop focus lesson in Reading Strategy #8; there are many more in The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension].

Also: If time allows, teachers can take at the end of every day to read aloud a chapter from a short well-written grade-appropriate text.

- So teachers can model, and readers can hear, fluent and expressive reading

- For including material that is above students’ reading levels – listening levels are generally higher than reading levels

- If there is material for which I particularly want to be able to stop at certain points (i.e., for a lesson on the reading strategy Prediction)

However, I see posts from teachers who are reading aloud all the novels they are “teaching,” or rather, novels through which they are teaching reading strategies and meeting standards.

In my classroom and those I have visited, I read aloud every day, but I read aloud the short mentor texts used for my Reading and Writing Workshop Focus Lessons—poems, picture books, short stories, news articles, and excerpts.

When reading aloud entire novels, there are some problems:

- Time – it takes a very long time to read a novel aloud. My students, many former reluctant readers, read about 10-20 books/year as whole-class, book club, and individual self-selected texts [See "Losing the Fear of Sharing Control: Starting a Reading Workshop"]

- Absenteeism – there will be students who miss parts of the novel being read and. even if there is a recap each day, they are still not hearing the entire novel—and the recap adds even more time.

- Not all students are actively listening all the time, maybe not on purpose, but minds wander (which is why I don’t listen to audio texts myself). To engage students many teachers stop frequently and ask questions, which is not natural reading and leads to teacher-generated questions about the text, rather than student-generated questions at the actual times they, as readers, would have questions of the text.

- Read-alouds do not make allowances for reading fix-it strategies, such as re-reading; in many cases it is the teacher who is processing the text for the readers.

- If students are reading along in a text, it is difficult to match their individual pace(s) to the read aloud.

- Many texts, such as verse novels and graphic novels, do not lend themselves to reading aloud. I feel that the power of verse novels is in seeing the word placement on the page, especially the line breaks. When I read a free verse poem aloud, I try to pause at the line break for less time than at the end of a “sentence” or even for a comma, but it doesn’t have the same impact. And even if a teacher is projecting a graphic novel or students have copies, visual reading skills improve with matching the text and the graphics; there are also decisions readers make on whether to read the graphic or the words first and, in some novels, deciphering the author’s intended reading order of the panels.

- Last, reading improves reading.

STRATEGY: Read aloud a short text, or passage, every day as part of the Workshop mini-lesson. [See my sample Reading Workshop focus lesson in Reading Strategy #8; there are many more in The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension].

Also: If time allows, teachers can take at the end of every day to read aloud a chapter from a short well-written grade-appropriate text.

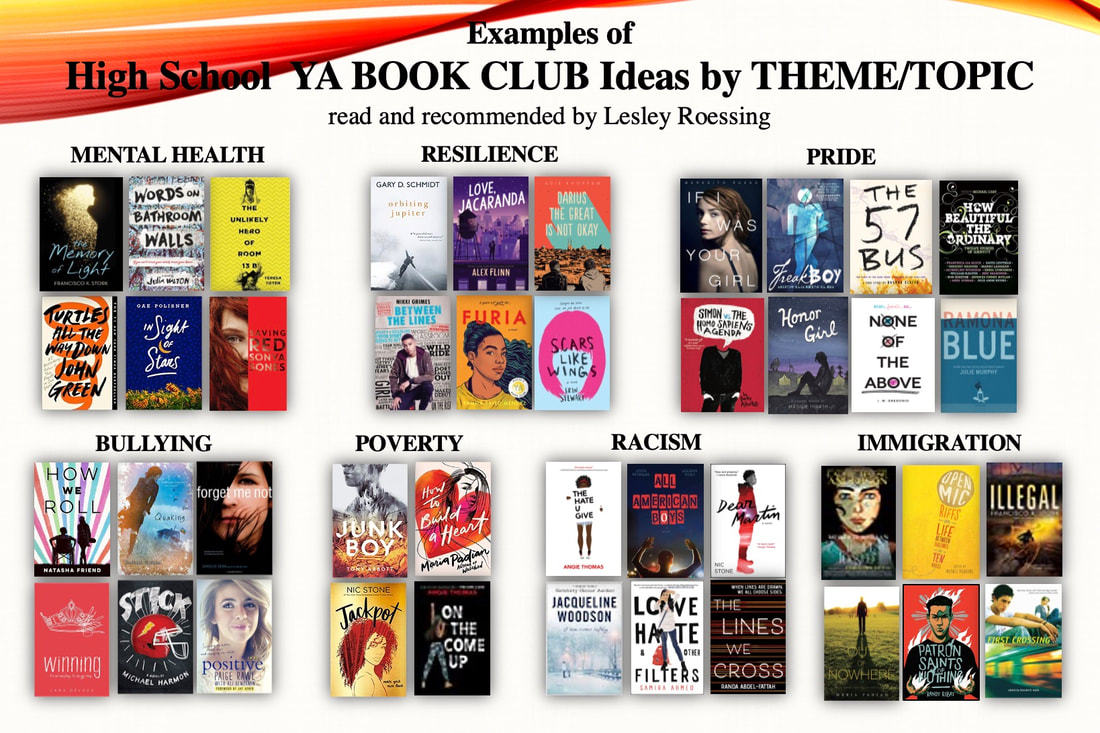

17. SUMMER READING

If you or your school requires a Summer Reading, you may consider offering a CHOICE of novels on a topic or theme, letting readers choose novels based on their own reading comfort levels from a variety of authors, characters, settings, and formats—prose, verse, and graphic.

When students return to school, they can group themselves into BOOK CLUBS to discuss their novels and prepare presentations to the rest of the class, thereby creating a Reading Community at the very beginning of the year. Students who transfer into the school on the first days can read a short story and conduct some light research on the topic to add to a club’s presentation.

To view a variety of novels written in various formats by diverse authors and featuring diverse characters on, at this time, 21 different THEMES, see the BOOK REVIEWS drop-down menu. There were also a few more themes—Earth Day, Siblings, Pets—posted this April on my FB page, and I add frequently.

If you or your school requires a Summer Reading, you may consider offering a CHOICE of novels on a topic or theme, letting readers choose novels based on their own reading comfort levels from a variety of authors, characters, settings, and formats—prose, verse, and graphic.

When students return to school, they can group themselves into BOOK CLUBS to discuss their novels and prepare presentations to the rest of the class, thereby creating a Reading Community at the very beginning of the year. Students who transfer into the school on the first days can read a short story and conduct some light research on the topic to add to a club’s presentation.

To view a variety of novels written in various formats by diverse authors and featuring diverse characters on, at this time, 21 different THEMES, see the BOOK REVIEWS drop-down menu. There were also a few more themes—Earth Day, Siblings, Pets—posted this April on my FB page, and I add frequently.

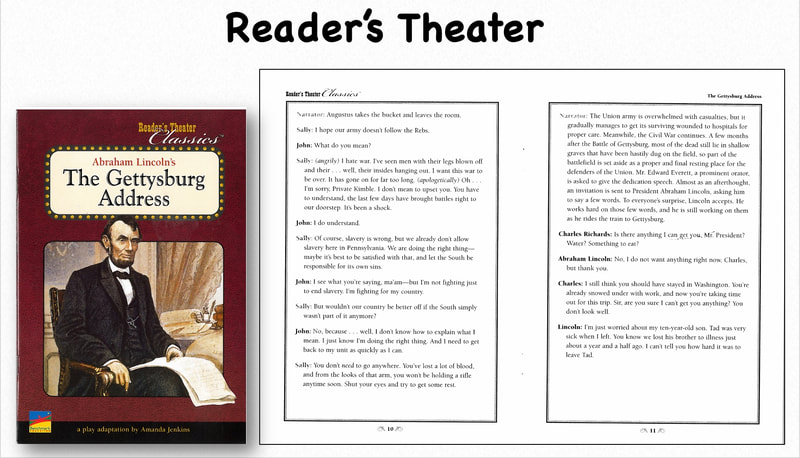

16. READER'S THEATER:

A Collaborative Reading-Writing-Speaking Activity

A Collaborative Reading-Writing-Speaking Activity

- Students form groups of 4-5 readers.

- Each group reads and discusses a short story.

- Each group turns their short story into a 5-10 minute Readers' Theater script (no costumes, no sets or props, no movement)

- Readers practice effective speech techniques (voice projection, variations in vocal speed, enunciation, emotion, inflection, posture, gestures, facial expressions—see Speaking Strategy #1.

- Each group presents their story with 4-5 characters/actors or with a narrator and 3-4 characters to the rest of the class.

- Alternative: After reading a whole-class novel, 5-6 groups each take a major story plot event and turn into a Readers' Theater script and perform the story in chronological order for themselves or another class.

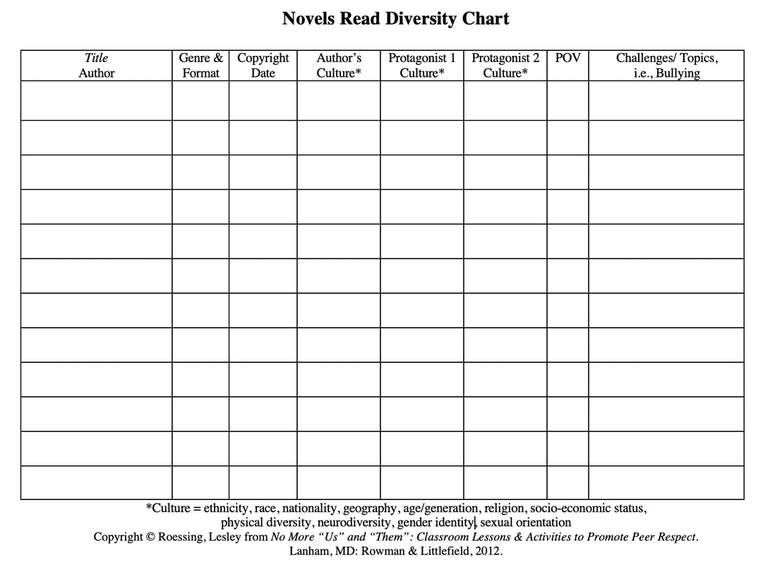

15. ENCOURAGING DIVERSE READING

To encourage students to read diversely, I created this chart so readers can track the diversity (and variety) of their reading over the term.

To encourage students to read diversely, I created this chart so readers can track the diversity (and variety) of their reading over the term.

For Book Club selections, offer choices by diverse authors, featuring diverse characters, settings, reading levels and formats (prose, verse, graphic, and multi-formatted), written from a variety of POVs. See "Planning A Diverse Library and my graphic lists of suggestions for Book Clubs for diverse reading.

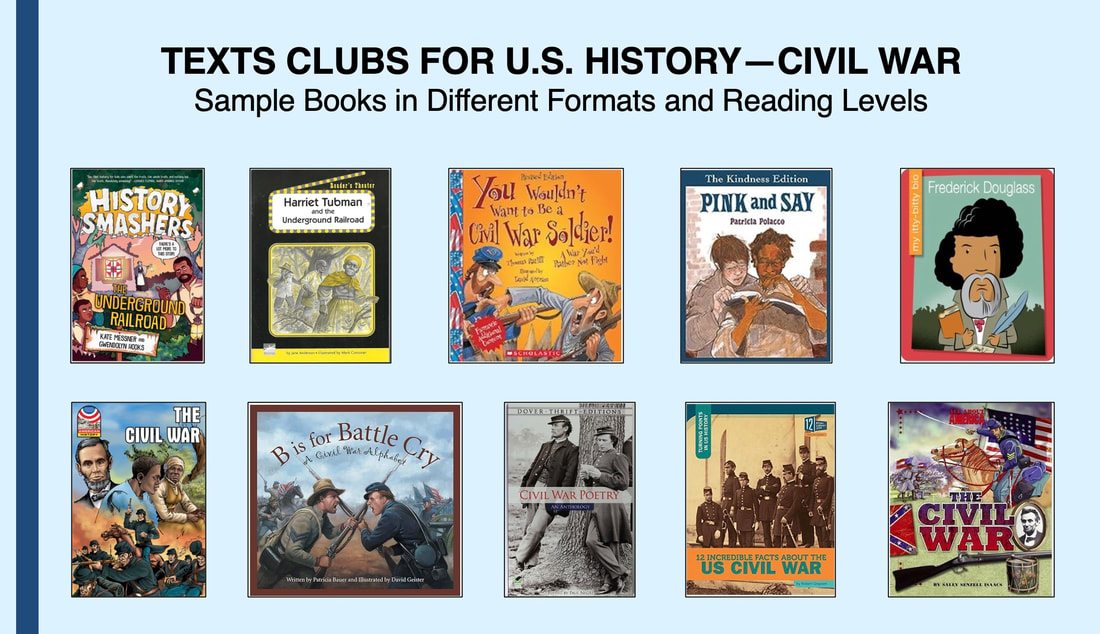

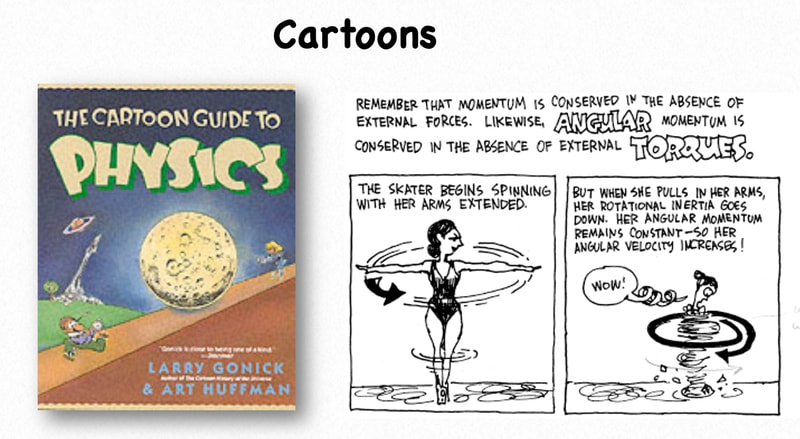

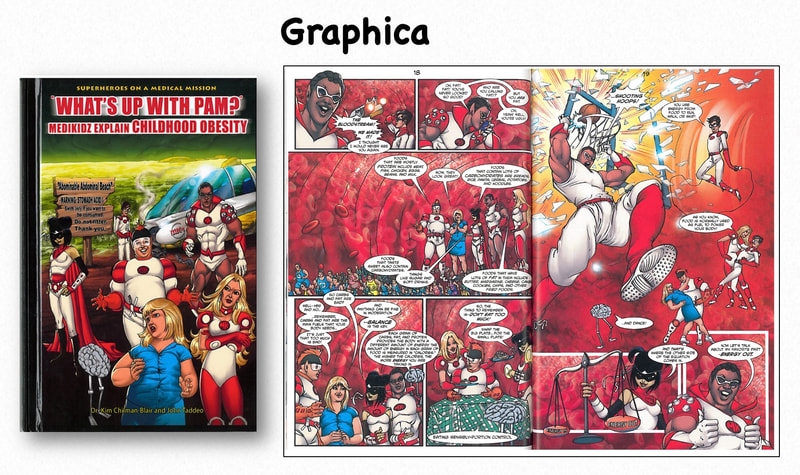

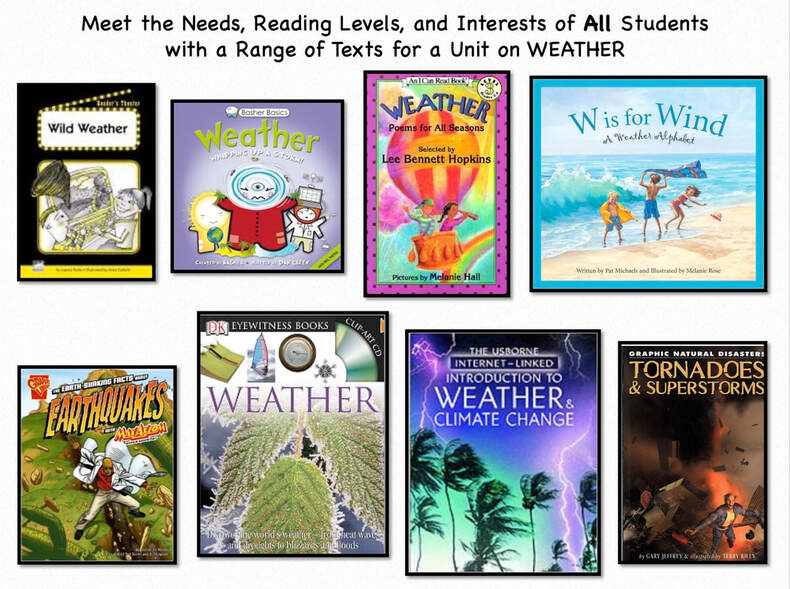

14. READING INFORMATIVE TEXTS in a variety of formats and in a range of reading levels

The range of reading levels, and the diverse formats of these sample texts will appeal to different readers while offering similar information but differentiation.

Below is a sample TEXT SET for a Science unit:

The range of reading levels, and the diverse formats of these sample texts will appeal to different readers while offering similar information but differentiation.

Below is a sample TEXT SET for a Science unit:

And a sample TEXT SET for a History unit:

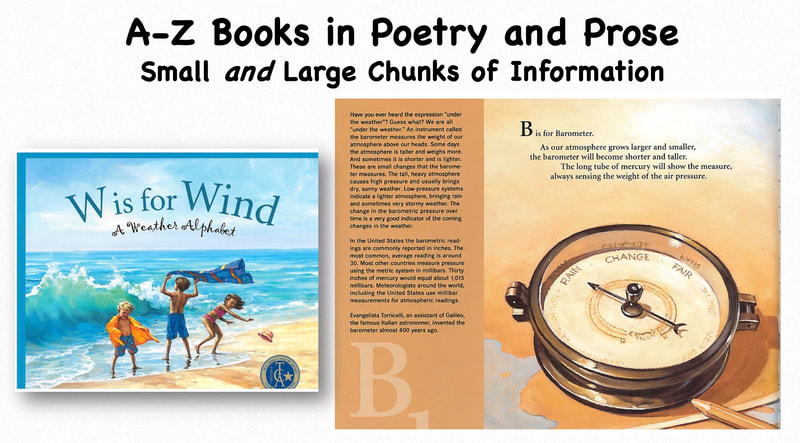

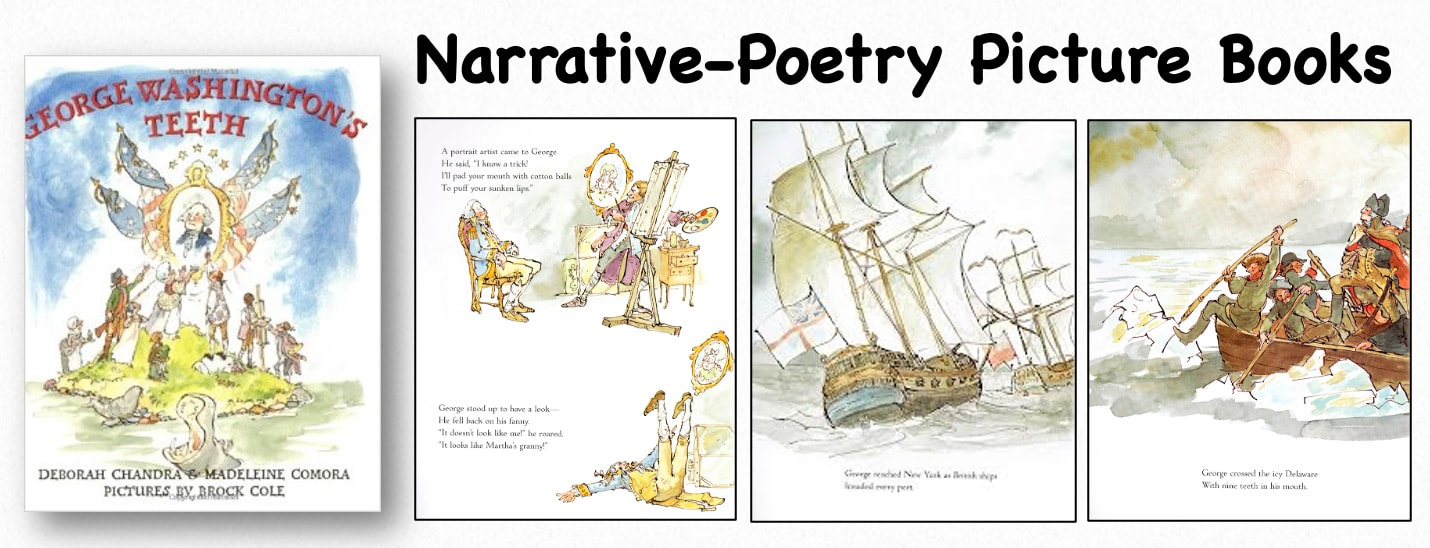

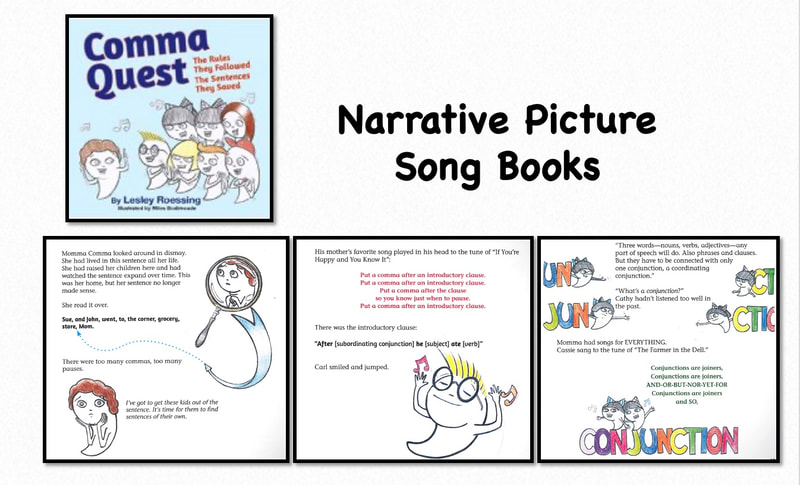

Informative Texts are available written in a variety of FORMATS: Reader's Theater, Cartoons and Graphica, A-Z Books, Poetry, Picture Books, etc.

Ideas, strategies, and lessons for setting up INFORMATIVE TEXT (Book) CLUBS are outlined in Talking Texts : A Teachers' Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum, Ch 9. Book Clubs can each read a text on a different, but related topic; Book Clubs can each read a different text on a whole-class topic; or Book Club members can each read a different text on a Book Club topic.

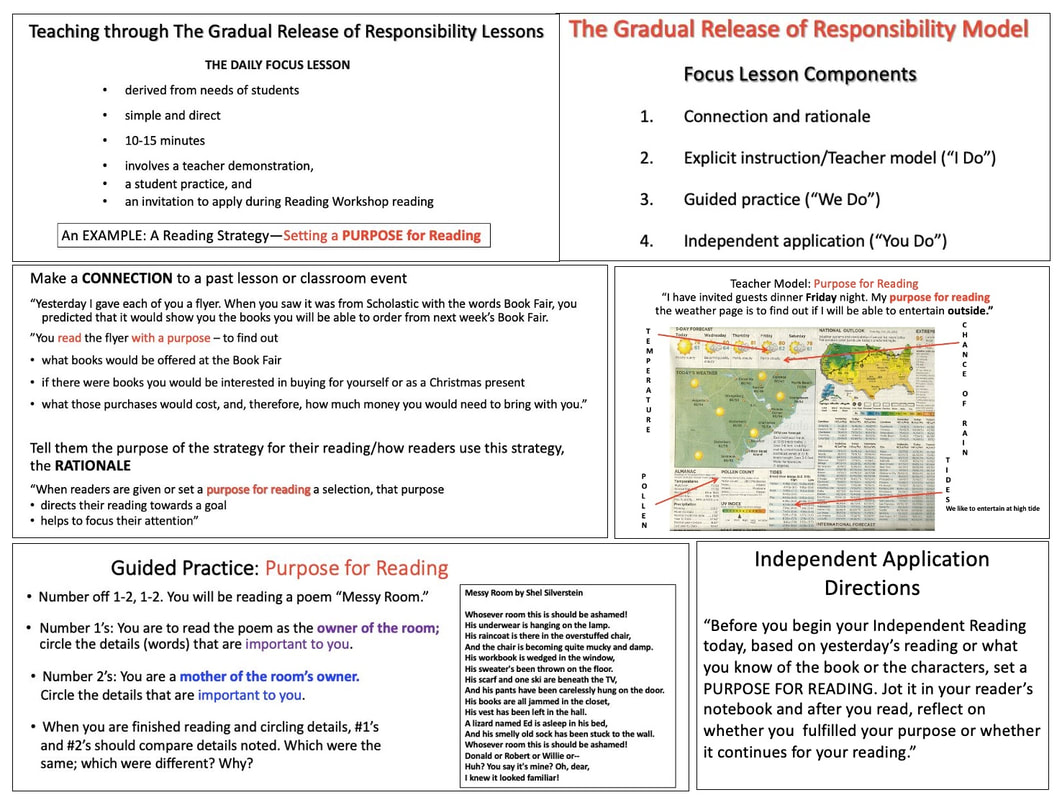

13. Another SAMPLE READING WORKSHOP FOCUS LESSON: Setting a Purpose for Reading

This is an example for a 10-15 minute Reading strategy lesson—Setting a Purpose for Reading—using one short text (newspaper article) for the Teacher Model and another short text (poem) for the Guided Practice and readers' whole-class, book club, or independent text for the Independent Application.

This is an example for a 10-15 minute Reading strategy lesson—Setting a Purpose for Reading—using one short text (newspaper article) for the Teacher Model and another short text (poem) for the Guided Practice and readers' whole-class, book club, or independent text for the Independent Application.

Another way to keep the Focus Lessons short is to use the same text—a poem, a picture book, a news article—for the Teacher Model (the beginning of the text) and for the Guided practice (the next part of the text); if the lesson is based on the chapter of a whole-class text, readers can finish the chapter for the Independent Application of the lesson.

See also Strategy #8, a sample Focus Lesson on Making Predictions

See also Strategy #8, a sample Focus Lesson on Making Predictions

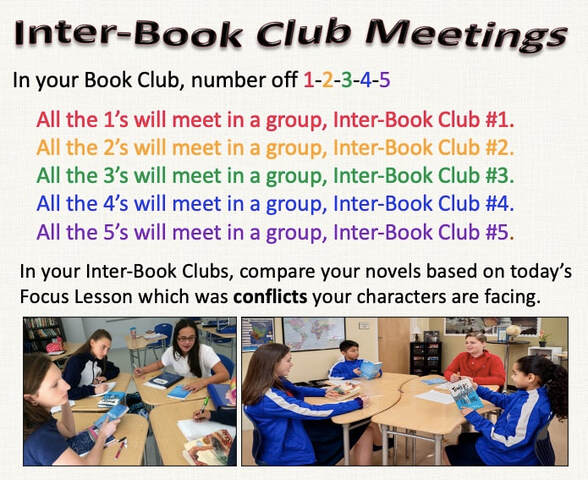

12. INTER-BOOK CLUB MEETINGS

After readers hold their 20-minute Book Club meeting, Book Club members meet for 5-10 minutes in small groups with other Book Clubs to compare/contrast their novels and characters. See sample instructions.

Add to the strategies in my blog "The 5 Steps of Facilitating Book Clubs."

After readers hold their 20-minute Book Club meeting, Book Club members meet for 5-10 minutes in small groups with other Book Clubs to compare/contrast their novels and characters. See sample instructions.

Add to the strategies in my blog "The 5 Steps of Facilitating Book Clubs."

This is another Book Club strategy from TALKING TEXTS: A Teachers' Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum.

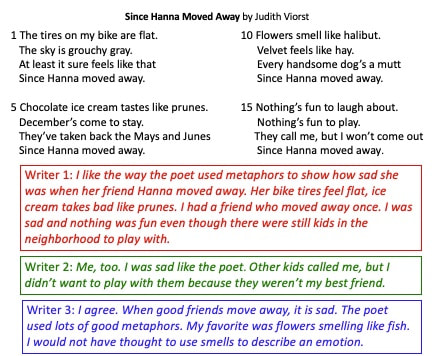

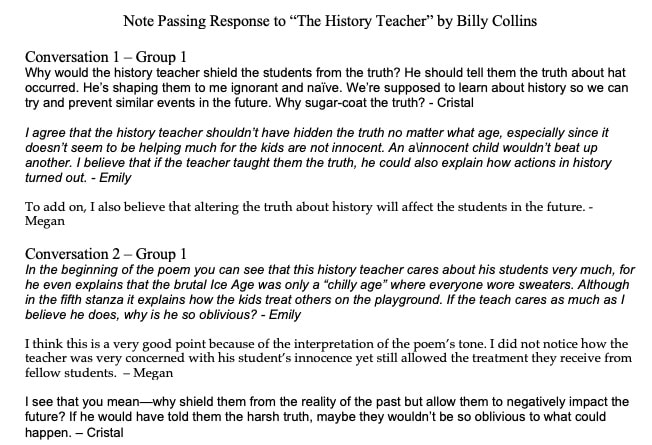

11. NOTEPASSING AS A DISCUSSION STRATEGY

When I ask teachers how many students typically participate in a class discussion, the answer is always, “Three to four—and always the same students.”

How do we encourage all students to participate in a discussion and how does this work with time and noise constraints?

Students love to write and pass notes—secret missives meant for the eyes of one person at a time. And notes allow time to plan a response and the knowledge that the response will be read and considered. Also, the fact that they do not need to look someone in the eye when making a response is comforting to many of our students. Teachers can effectively employ this technique in their classrooms through a discussion strategy: NOTEPASSING.

After teaching students how to initiate conversations with reflections that will invite further discussion and teaching some discussion “extenders” [see Strategy #9], I introduce Notepassing as a discussing strategy.

These are the teacher’s oral directions from my article “During Reading Response: Notepassing Discussion”:

Both teachers and students have seen the many advantages of this type of conversation which include

While I could have posted this as a Speaking or Writing Strategy, I decided to post it as a Reading Strategy because it is extremely effective when discussing text—novels, short stories, poetry, articles, and even textbook chapters.

How do we encourage all students to participate in a discussion and how does this work with time and noise constraints?

Students love to write and pass notes—secret missives meant for the eyes of one person at a time. And notes allow time to plan a response and the knowledge that the response will be read and considered. Also, the fact that they do not need to look someone in the eye when making a response is comforting to many of our students. Teachers can effectively employ this technique in their classrooms through a discussion strategy: NOTEPASSING.

After teaching students how to initiate conversations with reflections that will invite further discussion and teaching some discussion “extenders” [see Strategy #9], I introduce Notepassing as a discussing strategy.

These are the teacher’s oral directions from my article “During Reading Response: Notepassing Discussion”:

- Divide into groups of three [the best number for this activity. If there needs to be 1-2 groups of four, those groups may make another pass—see #6.] After you divide into groups, there is to be no talking.

- Each student is to individually read the article (or textbook chapter or the next novel chapter).

- On a separate sheet of paper, write a two-minute response to the text. Think of something meaningful, significant, or interesting to write about—a good discussion point. Write or print legibly so what you write can be read by others. Then sign your first name. [When the timer signals two minutes, the teacher tells students to finish the sentence they are currently writing and sign their names.]

- Within your triad, pass your paper to the right. Write a two-minute response to the comments made by the person whose paper you receive, continuing the conversation as we discussed. Then sign your name.

- Again pass the papers to the right within your triad. Read the two responses. Write a two-minute response to the comments on the paper you receive, continuing and extending the conversation started by the first two responders; then sign your first name. [When the timer signals two minutes, the teacher tells students to finish the sentences they are currently writing and sign their names.]

- Return the note to its original owner who will read all the responses. [During this time, groups of four can pass and write one more time if the teacher wishes.]

- Your group should now talk about insights or points made in their comments.

- THEN each triad prepares to share with the class:

- The different topics of your “conversations”

- One point about the text on which you all agree and think is important

Both teachers and students have seen the many advantages of this type of conversation which include

- Everyone participates and has a turn

- Everyone has some time to think about their responses

- With even 30 students “discussing,” the room is quiet

- There were no non-verbal reactions to comments

- All comments have an audience

- All students are writing at the same time, so there are actually 3 conversations going on in each group (only 1-2 are shown below).

While I could have posted this as a Speaking or Writing Strategy, I decided to post it as a Reading Strategy because it is extremely effective when discussing text—novels, short stories, poetry, articles, and even textbook chapters.

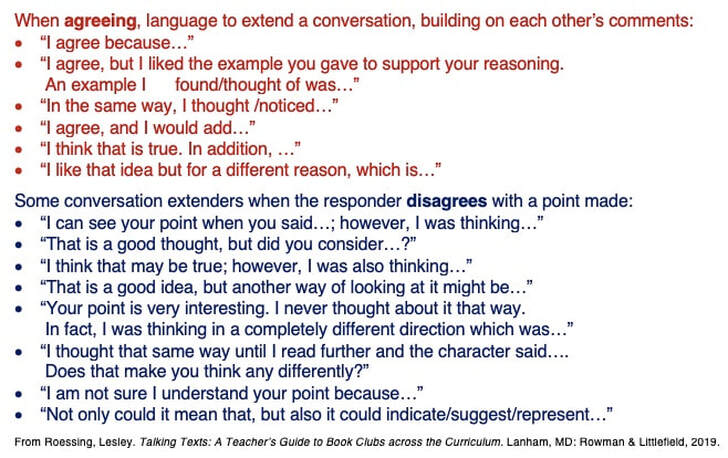

10. TEACHING DISCUSSION STRATEGIES

It is important, especially when facilitating class or small group discussions, to teach students strategies to develop conversations, especially when everyone agrees with a point that has been made. Students need to practice strategies that extend conversations, building on each other's comments and insights. In promoting productive conversations, it is even more essential to teach the language to respectfully disagree. Disagreements, when held while valuing everyone's opinion, may lead to even more in-depth discussion.

This chart is from Talking Texts: A Teacher's Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum which explores this topic in more detail.

It is important, especially when facilitating class or small group discussions, to teach students strategies to develop conversations, especially when everyone agrees with a point that has been made. Students need to practice strategies that extend conversations, building on each other's comments and insights. In promoting productive conversations, it is even more essential to teach the language to respectfully disagree. Disagreements, when held while valuing everyone's opinion, may lead to even more in-depth discussion.

This chart is from Talking Texts: A Teacher's Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum which explores this topic in more detail.

9. "TEACHING" THE WHOLE-CLASS NOVEL

We are not teaching readers to read a novel; we are teaching them to read novels, moving them to independence so they can apply the strategies we teach to any novel they read and, hopefully, making them lifelong readers.

Step 1: Determine what LESSONS you want to use the novel to teach: reading strategies, literary elements, author’s craft, response,…. Plan daily reading Workshop Focus Lessons (see Reading Strategy #8). We are teaching readers, not novels.

Step 2: Determine any background knowledge readers need to have, i.e. historical fiction , or if reading the novel will provide that information. See Reading Strategy # 1 for a KWHLR Chart for determining/activating prior knowledge.

Step 3: Divide the novel into reading chunks: 1-2 chapter(s)/day or a few chapters to discuss every other day (alternating with Writing Workshop days).

Step 4: Determine how to assess if and how readers are reading and comprehending, i.e. teaching Reading Response strategies.

Step 5: Plan After-Reading Assessment/Presentation or choices.

Read novel through Reading Workshop Format:

Step 2: Determine any background knowledge readers need to have, i.e. historical fiction , or if reading the novel will provide that information. See Reading Strategy # 1 for a KWHLR Chart for determining/activating prior knowledge.

Step 3: Divide the novel into reading chunks: 1-2 chapter(s)/day or a few chapters to discuss every other day (alternating with Writing Workshop days).

Step 4: Determine how to assess if and how readers are reading and comprehending, i.e. teaching Reading Response strategies.

Step 5: Plan After-Reading Assessment/Presentation or choices.

Read novel through Reading Workshop Format:

All novels do not need to be read as whole-class novels. I moved from short stories > whole-class novel > Book Club novels > independent, self selected novels (sometimes on the same topic or in the same format or genre (see "Losing the Fear of Sharing Control: Starting a Reading Workshop").

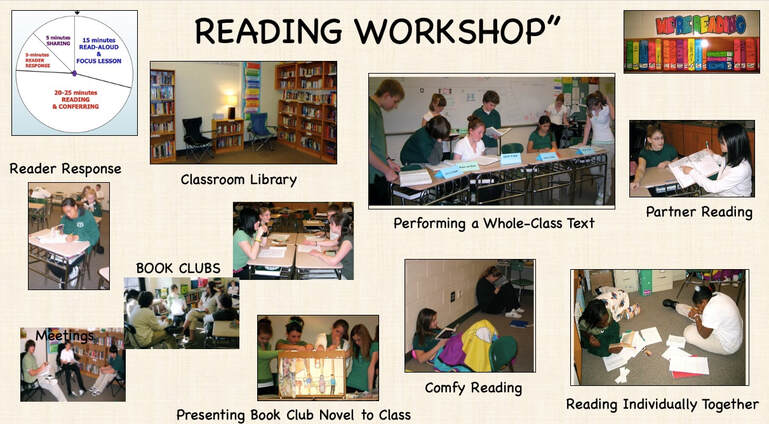

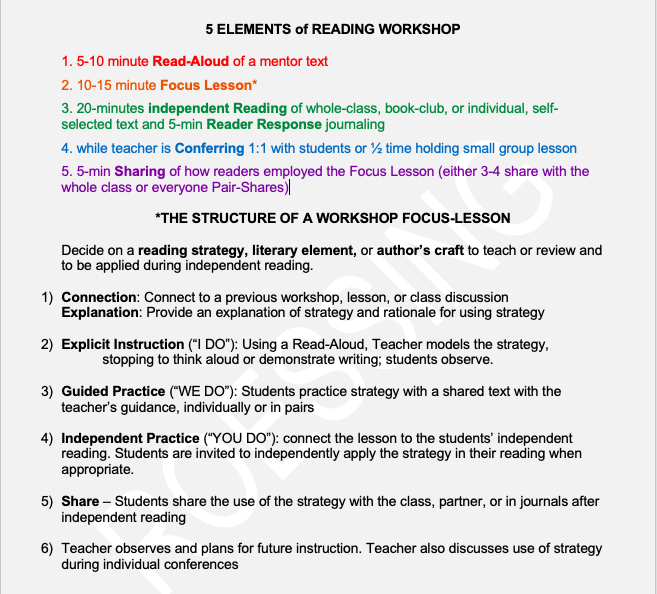

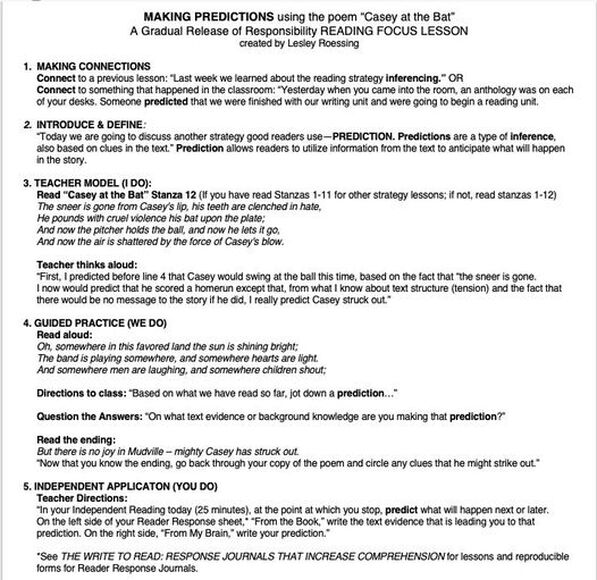

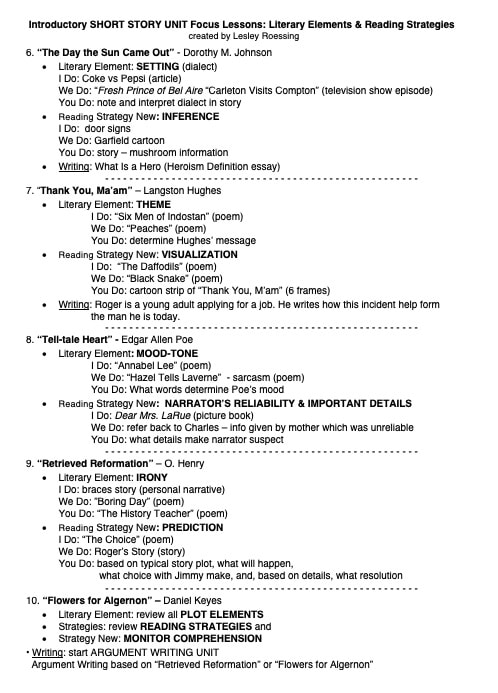

8. A SAMPLE READING WORKSHOP FOCUS LESSON: Making Predictions

This is an example of designing a Reading/Writing FOCUS LESSON or GRADUAL RELEASE OF RESPONSIBILITY LESSON or READING STRATEGY LESSON (actually this is all 3 together). This was the format I used for teaching all my Reading and Writing Workshop Daily Focus Lessons, teaching narrow concepts in each lesson, teaching to Mastery.

For more about the Gradual Release of Responsibility model, see https://www.literacywithlesley.com/blog/teaching-through-the-gradual-release-of-responsibility-model

This is an example of designing a Reading/Writing FOCUS LESSON or GRADUAL RELEASE OF RESPONSIBILITY LESSON or READING STRATEGY LESSON (actually this is all 3 together). This was the format I used for teaching all my Reading and Writing Workshop Daily Focus Lessons, teaching narrow concepts in each lesson, teaching to Mastery.

For more about the Gradual Release of Responsibility model, see https://www.literacywithlesley.com/blog/teaching-through-the-gradual-release-of-responsibility-model

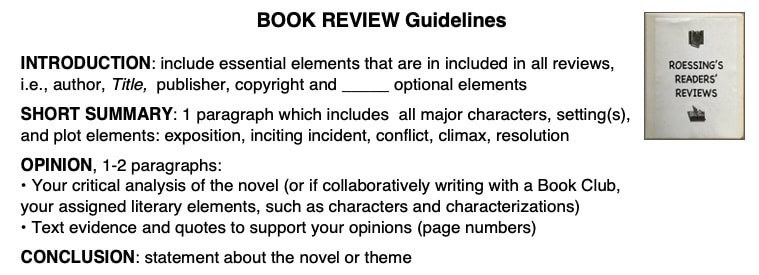

7. STUDENT BOOK REVIEWS TO SHARE READING

Strategies for readers to share books they read with other readers:

1) Each marking period my readers were required to write a formal BOOK REVIEW (argument writing). We scaffolded as follows:

MARKING PERIOD 1: The CLASS first analyzed 3 published book reviews as mentor texts, noting elements that were included in ALL reviews and elements included in only SOME reviews. The "All" became required elements for their reviews; the "Some" were optional. I required a certain number of "optional" elements, differentiating.

The class then wrote a review together, critiquing our whole-class novel. Students brainstormed ideas together, collaborated on appropriate language, and then readers wrote individual reviews (or in pairs), using as much from the class discussions as they wished.

MARKING PERIOD 2: BOOK CLUB members collaborated on a Book Review, critiquing their Book Club novel, each member analyzing a different literary element.

MARKING PERIODS 3 and 4: Readers INDIVIDUALLY choose 1 of their self-selected, independently-read texts to review.

Reviews were typed and illustrated, usually with a picture of the cover, and housed in the Roessing Readers' Reviews binder which was divided by genre (as was our classroom library) for readers to peruse when looking for a next book to read.

√These also could be uploaded to a class, teacher, or library computer as a digital binder.

Pictured are my GUIDELINES FOR REVIEWS. See The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension and Talking Texts: A Teachers' Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum for student samples and other ways readers shared their readings, individually and collaboratively.

Also, scroll down to the BOOK TALKS short.

1) Each marking period my readers were required to write a formal BOOK REVIEW (argument writing). We scaffolded as follows:

MARKING PERIOD 1: The CLASS first analyzed 3 published book reviews as mentor texts, noting elements that were included in ALL reviews and elements included in only SOME reviews. The "All" became required elements for their reviews; the "Some" were optional. I required a certain number of "optional" elements, differentiating.

The class then wrote a review together, critiquing our whole-class novel. Students brainstormed ideas together, collaborated on appropriate language, and then readers wrote individual reviews (or in pairs), using as much from the class discussions as they wished.

MARKING PERIOD 2: BOOK CLUB members collaborated on a Book Review, critiquing their Book Club novel, each member analyzing a different literary element.

MARKING PERIODS 3 and 4: Readers INDIVIDUALLY choose 1 of their self-selected, independently-read texts to review.

Reviews were typed and illustrated, usually with a picture of the cover, and housed in the Roessing Readers' Reviews binder which was divided by genre (as was our classroom library) for readers to peruse when looking for a next book to read.

√These also could be uploaded to a class, teacher, or library computer as a digital binder.

Pictured are my GUIDELINES FOR REVIEWS. See The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension and Talking Texts: A Teachers' Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum for student samples and other ways readers shared their readings, individually and collaboratively.

Also, scroll down to the BOOK TALKS short.

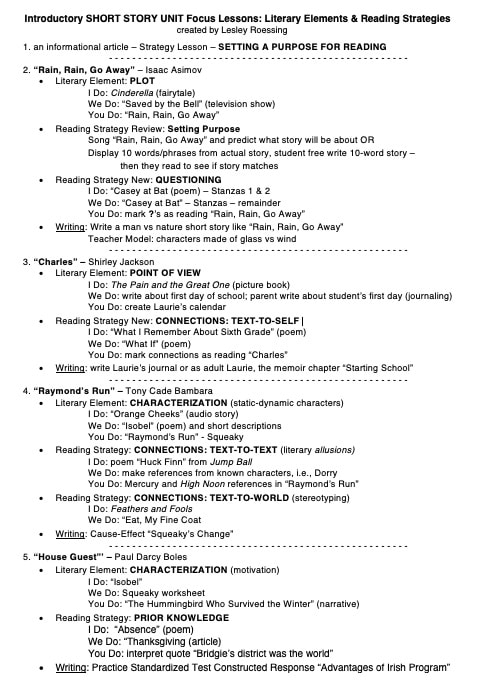

6. TEACHING READING STRATEGIES & LITERARY ELEMENTS through SHORT STORIES

|

At the beginning of each year, I employed shorts stories to teach reading strategies, such as

And for teaching/reviewing literary elements, such as

For each lesson on the first day I taught a literary element and we read about half the story. The second day I taught a reading strategy lesson, and we usually finished the story. In some cases we had a quick review of the previous lesson using the new text. We read the stories in a variety of ways: I read aloud, modeling fluent, expressive reading; students volunteered to read the dialogue as the characters, and I read the narration, much like Readers' Theater: I read the beginning of the story and then students read individually to themselves to a certain point in the story. Then readers were given a short writing assignment, many times just taken to the draft stage. All lessons were taught through the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model [see my GRR Blog]. For the first lesson on Activating Background Knowledge, we read a short informational article, first filling out the What I KNOW (or think I know) and the What I WANT to Know parts of a K-W-L Chart to activate background knowledge of any kind associated, no matter how tenuously, to the topic or title of the article. Pictured are lessons with 9 short stories. In my case the stories all came from our Prentice Hall anthology; I chose the stories that best fit each lesson I was teaching. And also pictured is an expanded sample lesson. |

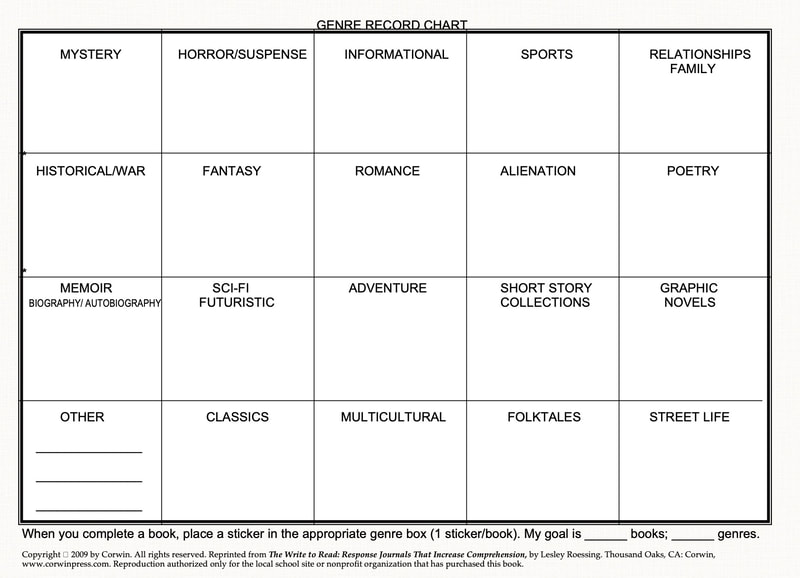

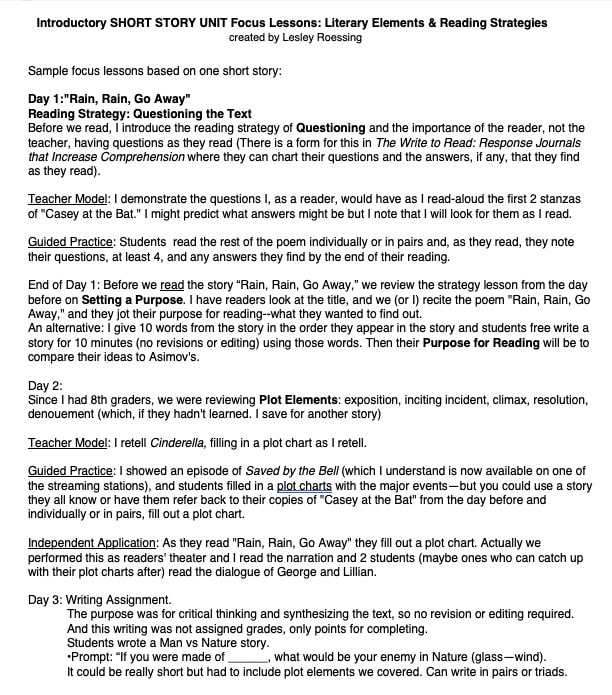

5. GENRE RECORD CHART to ENCOURAGE WIDE READING

I designed this chart for students' Reading Journals to encourage readers to try different GENRES.

1.After readers finished a book—whether a whole-class, book club, or independent self-selected reading, they placed a star sticker in the appropriate square.

2. Whenever readers accumulated 3 stars in one genre, they were encouraged to try another genre. It was not necessary to acquire 3 stars in every block but to at least try 1 book in as many as possible.

Of course, teachers can include any genres, or even formats—prose, verse, graphic, multi-formatted, they wish; this chart represents how our classroom library was designated.

There was no prize or grade for number of stars or number of squares; the chart provided a visual record of their reading for readers and for me and one basis of self-reflection of themselves as readers. I did overhear 8th graders make such comments to each other as, “I see you have been reading quite a lot of genres. How did you like …” or, about themselves, “I never thought I would like reading ….”

In its blank format, this is one of the many reproducible forms for readers’ journals from THE WRITE TO READ: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension.

1.After readers finished a book—whether a whole-class, book club, or independent self-selected reading, they placed a star sticker in the appropriate square.

2. Whenever readers accumulated 3 stars in one genre, they were encouraged to try another genre. It was not necessary to acquire 3 stars in every block but to at least try 1 book in as many as possible.

Of course, teachers can include any genres, or even formats—prose, verse, graphic, multi-formatted, they wish; this chart represents how our classroom library was designated.

There was no prize or grade for number of stars or number of squares; the chart provided a visual record of their reading for readers and for me and one basis of self-reflection of themselves as readers. I did overhear 8th graders make such comments to each other as, “I see you have been reading quite a lot of genres. How did you like …” or, about themselves, “I never thought I would like reading ….”

In its blank format, this is one of the many reproducible forms for readers’ journals from THE WRITE TO READ: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension.

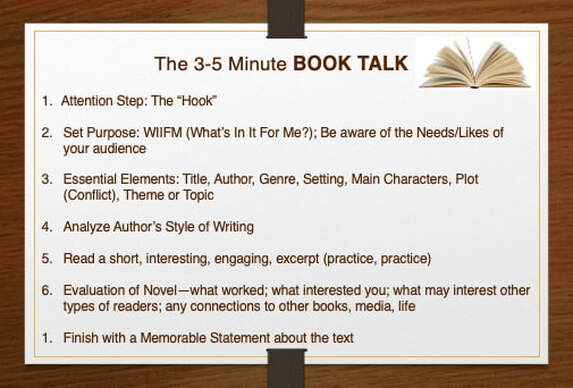

4. BOOK TALK GUIDELINES

A BOOK TALK is an oral presentation by a teacher, librarian, or student-reader who tells about a book to stimulate other readers’ interest and encourage and motivate them to read a text – an “AD” for a book.

1. Besides teacher and librarian Book Talks, to introduce readers to more texts, invite student-readers to sign up in advance for extra-credit Book Talks. Teachers/Librarians will then know when to plan for 5 minutes at the end of an upcoming class.

2. Teachers need to teach effective Public Speaking Techniques first: volume, enunciation, pacing, eye contact, posture.

3. In order to present and earn extra credit, the presentation needs to be practiced and fit the time limit.

4. Presenters are to have a copy of the book or be able to project a picture of the front cover.

1. Besides teacher and librarian Book Talks, to introduce readers to more texts, invite student-readers to sign up in advance for extra-credit Book Talks. Teachers/Librarians will then know when to plan for 5 minutes at the end of an upcoming class.

2. Teachers need to teach effective Public Speaking Techniques first: volume, enunciation, pacing, eye contact, posture.

3. In order to present and earn extra credit, the presentation needs to be practiced and fit the time limit.

4. Presenters are to have a copy of the book or be able to project a picture of the front cover.

3. PRE-READING FREE-WRITE ACTIVITY to Set a Purpose for Reading

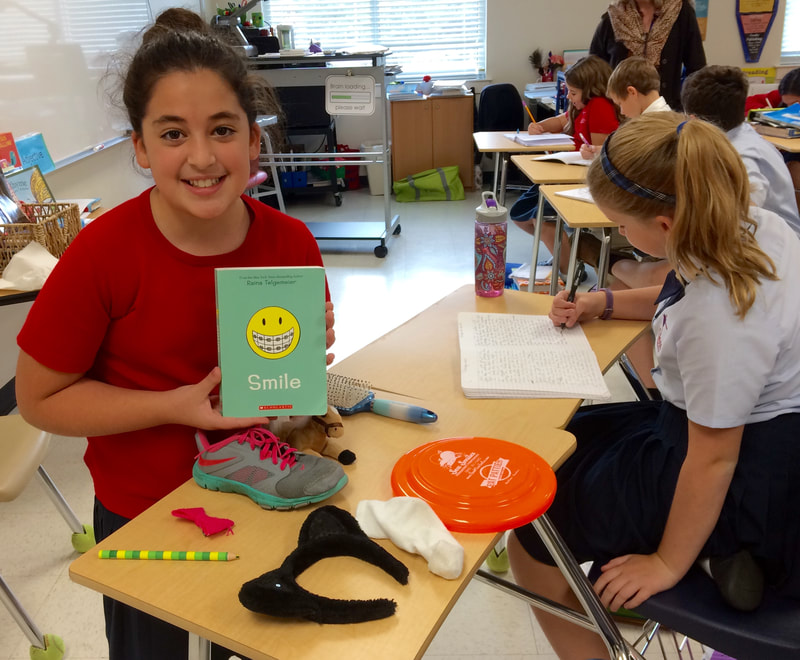

OBJECTS STORY, a PRE-READING ACTIVITY: Students draft a story based on 10 objects from a text they will read.

1. Writers begin their individual stories. Sometimes I started writers off with the opening sentence from the text to be read or a sentence that would set the mood.

2. After students have drafted a sentence or two, I pull 10 objects from a box or bag; pulling out one object every minute.

3. As I pull and announce an object, writers have to include the object within their next sentence or two, until they have included all 10 objects and a final sentence. Writers are not to worry about mechanics.

3. When we finish, writers can share their stories.

These are not finished writings; they may not even make much sense. As with our daily free-writes (see Strategy Short below), the focus is Writing Fluency (and making writing fun). When I tell writers that the author has used these same items in their story, the student writings lead to anticipation about the text; readers cannot wait to read and find out how these objects fit in the story (purpose for reading).

I have used this strategy/activity with Langston Hughes' "Thank You, Ma'am," but it would work with any story or novel.

Visiting a classroom where a teacher from one of my workshops introduced this activity to her students, I watched a student employ it as part of a Book Talk for her class, asking students to write a story as she pulled objects from her novel. After 2-3 students shared their drafts, Brianna presented her Book Talk on Smile.

[Pictures used with students, parents, and teacher permission].

1. Writers begin their individual stories. Sometimes I started writers off with the opening sentence from the text to be read or a sentence that would set the mood.

2. After students have drafted a sentence or two, I pull 10 objects from a box or bag; pulling out one object every minute.

3. As I pull and announce an object, writers have to include the object within their next sentence or two, until they have included all 10 objects and a final sentence. Writers are not to worry about mechanics.

3. When we finish, writers can share their stories.

These are not finished writings; they may not even make much sense. As with our daily free-writes (see Strategy Short below), the focus is Writing Fluency (and making writing fun). When I tell writers that the author has used these same items in their story, the student writings lead to anticipation about the text; readers cannot wait to read and find out how these objects fit in the story (purpose for reading).

I have used this strategy/activity with Langston Hughes' "Thank You, Ma'am," but it would work with any story or novel.

Visiting a classroom where a teacher from one of my workshops introduced this activity to her students, I watched a student employ it as part of a Book Talk for her class, asking students to write a story as she pulled objects from her novel. After 2-3 students shared their drafts, Brianna presented her Book Talk on Smile.

[Pictures used with students, parents, and teacher permission].

|

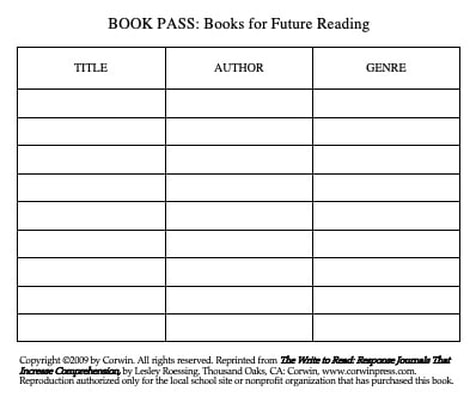

2. A BOOK PASS |

|

Directions:

Adaptation:

Purpose: to put books in the hands of readers.

In 10-15 minutes, students are exposed to 10-15 books which they can add to their "Book Pass: Books for Future Reading" chart in their reading journals, one of the reproducible forms from The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension (Corwin Press).

- Place a different book on each student's desk.

- Students have 1 minute to look at the front and back covers and read part of the first page (to see if they like the author's writing style and if they think the reading will be at their comfort level).

- After 1 minute on the timer, together they pass the book to the next student.

- Students write any titles that interest them for future reading on their Reading Journal chart [pictured above].

- If a student finds a novel they want to read and is ready for their next read, they take the novel out of circulation, replacing it with one from a pile placed on a nearby desk.

Adaptation:

- Put 5-6 desks in a circle.

- Place novels of a particular genre in the middle of each circle, i.e., Fantasy Novel circle, Romance Novel circle, Sports Fiction circle, Dystopian Lit circle, Graphic Novel circle.

- Students sit in the circle that most interest them, at least for their future reading.

- Book Pass proceeds within each circle as decribed above.

Purpose: to put books in the hands of readers.

In 10-15 minutes, students are exposed to 10-15 books which they can add to their "Book Pass: Books for Future Reading" chart in their reading journals, one of the reproducible forms from The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension (Corwin Press).

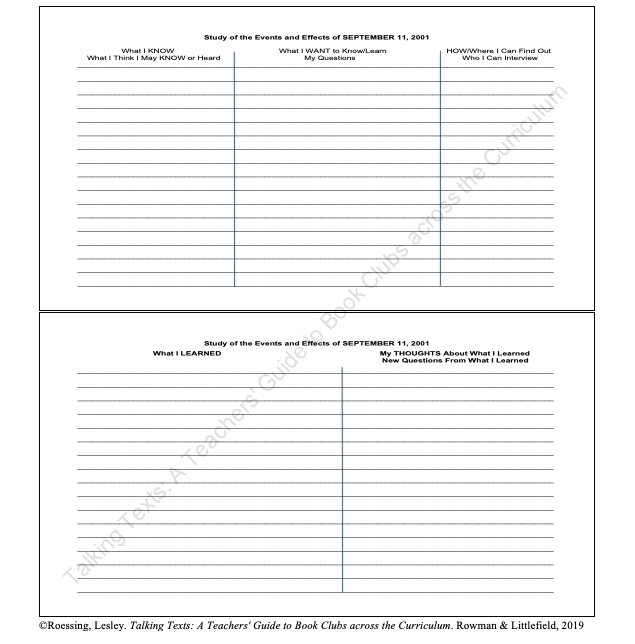

1. THE K-W-H-L-R CHART to Activate Prior Knowledge & Set Purpose for Reading

Beginning a new topic? See what your students already KNOW (activating background knowledge) and guide them to what they WANT/need to know and HOW and where they can find out. Then they notice what they LEARNED to finally promote REFLECTION to synthesize learning.

This is how I adapted the customary K-W-L chart to begin many of my units, especially in my Humanities class which covered Holocaust and Apartheid studies and Shakespeare.

This form is from my 9/11 Book Club unit in Chapter 10 TALKING TEXTS: A Teacher's Guide to Book Club across the Curriculum (Rowman & Littlefield) and can be used in all content areas

This is how I adapted the customary K-W-L chart to begin many of my units, especially in my Humanities class which covered Holocaust and Apartheid studies and Shakespeare.

This form is from my 9/11 Book Club unit in Chapter 10 TALKING TEXTS: A Teacher's Guide to Book Club across the Curriculum (Rowman & Littlefield) and can be used in all content areas

Proudly powered by Weebly