- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

- Asian, Asian-American

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

24. WRITING FOLDERS

To store student-writers' writings, I had a milk crate in a different color for each class.

My students each had a hanging writing folder in their class crate. Files were placed alphabetically. In each student's hanging folder were three manilla folders: SEEDS, SEEDLINGS, and PLANTS.

*1-2 students (usually the first in the room) would distribute the freewrite notebooks at the beginning of each class. To thank them I would give them a raffle ticket on which they wrote their name and placed in a small jar for their class period. At the end of the month I chose one ticket for a prize from the dollar store. The prize didn't really matter; they just liked winning.

Students also had Reader Response Notebooks (Writing -to-Learn notebooks) that I collected one a weekly basis (See #19 at https://www.literacywithlesley.com/reading-strategies.html).

My students each had a hanging writing folder in their class crate. Files were placed alphabetically. In each student's hanging folder were three manilla folders: SEEDS, SEEDLINGS, and PLANTS.

- In their SEEDS folder was their daily freewrite journal* (see Strategy #1), any brainstorming worksheets (such as those for memoir writing included in Bridging the Gap, and anything—pictures, words, etc.—they wanted to keep as a seed for a future writing;

- In SEEDLINGS were the draft they were working on as well as any other writings that writers only took to the draft stage (not all writings need to be taken to final publication to teach a writing style or format);

- PLANTS held their finished (published), assessed writings and that folder served as their Portfolio of writings which they could access to analyze and reflect on their progress at various times during the year. At the end of the year, they also could choose one piece to pass on to the next teacher and/or to submit to a class anthology.

*1-2 students (usually the first in the room) would distribute the freewrite notebooks at the beginning of each class. To thank them I would give them a raffle ticket on which they wrote their name and placed in a small jar for their class period. At the end of the month I chose one ticket for a prize from the dollar store. The prize didn't really matter; they just liked winning.

Students also had Reader Response Notebooks (Writing -to-Learn notebooks) that I collected one a weekly basis (See #19 at https://www.literacywithlesley.com/reading-strategies.html).

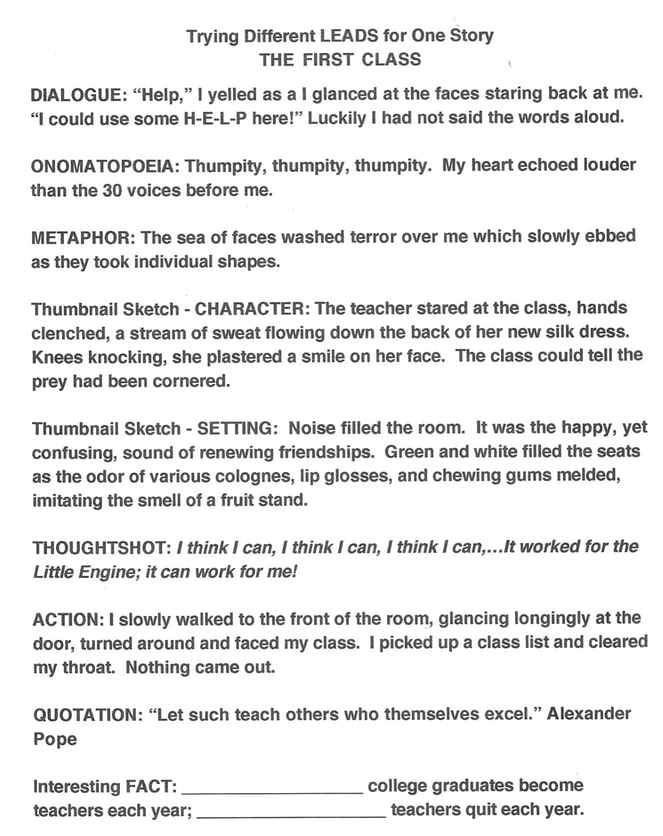

23. LEADS—a Writing Workshop Focus Lesson

Step 1: Use a MENTOR TEXT – a text with a good LEAD; it may be something that you already read in class.

Step 2: Give INSTRUCTION and RATIONALE for using the strategy:

A LEAD is the opening sentence(s) of your text. An effective lead draws readers in and makes them want more. The LEAD should capture the reader’s interest, introduce the topic, establish voice, and move smoothly into the text. A LEAD is critical because it

Step 3: Have students look at picture books, novels, short stories, etc. and RATE the LEADS according to the Step 2 criteria.

What makes the lead effective or not?

Step 4: Introduce TYPES of LEADS (for narrative writing). I would suggest teaching 1-2 types/writing, building writers' toolboxes

Step 5: Teacher Model: .

Step 1: Use a MENTOR TEXT – a text with a good LEAD; it may be something that you already read in class.

Step 2: Give INSTRUCTION and RATIONALE for using the strategy:

A LEAD is the opening sentence(s) of your text. An effective lead draws readers in and makes them want more. The LEAD should capture the reader’s interest, introduce the topic, establish voice, and move smoothly into the text. A LEAD is critical because it

- sets the TONE

- determines the CONTENT of the piece

- determines the DIRECTION of the piece

- establishes VOICE

- fuels the WRITING

- attracts and entices the READER

Step 3: Have students look at picture books, novels, short stories, etc. and RATE the LEADS according to the Step 2 criteria.

What makes the lead effective or not?

Step 4: Introduce TYPES of LEADS (for narrative writing). I would suggest teaching 1-2 types/writing, building writers' toolboxes

- DIALOGUE or THOUGHTS (INTERNAL MONOLOGUE)

- ONOMATOPOEIA (SOUND)

- METAPHOR

- CHARACTER SKETCH

- DESCRIPTION (SNAPSHOT) or IMAGE DETAIL

- ACTION

- INTRIGUING QUOTATION

- INTERESTING or STARTLING FACT

- ANECDOTE

Step 5: Teacher Model: .

Step 6: Guided practice: Give writers a short piece to, in pairs or triads, add a Lead

Step 7: Independent Application: Add a Lead to their draft

√ In other lessons for an Informational Writing, follow same steps for NONFICTION LEADS

Step 7: Independent Application: Add a Lead to their draft

√ In other lessons for an Informational Writing, follow same steps for NONFICTION LEADS

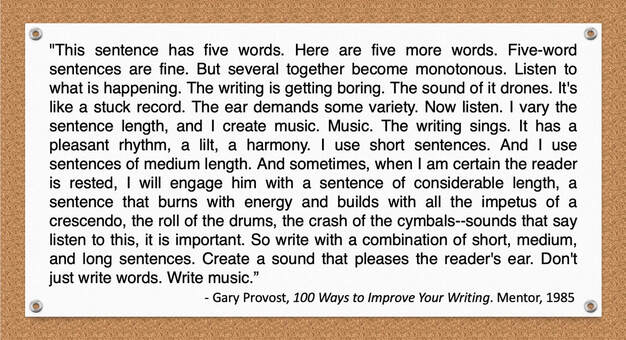

22. SENTENCE FLUENCY—BUILDING BETTER SENTENCES

Sentence Fluency is the rhythm and flow of the language, the sound of word patterns, the way in which the writing plays to the ear, not just to the eye. Sentences should be well crafted: varying in length, beginnings, structure, and style.

Sentence Fluency is the rhythm and flow of the language, the sound of word patterns, the way in which the writing plays to the ear, not just to the eye. Sentences should be well crafted: varying in length, beginnings, structure, and style.

SENTENCE FLUENCY TRAITS (6 Traits of Writing)

- Well-crafted sentences

- Variation in sentence types – simple, compound, complex, compound-complex,

- Variation in sentence lengths – compound subjects, compound predicates, phrases, clauses

- Variations in sentence beginnings

- Smooth and rhythmic “flow”

- Purposeful rule breaking for effect, i.e., fragments

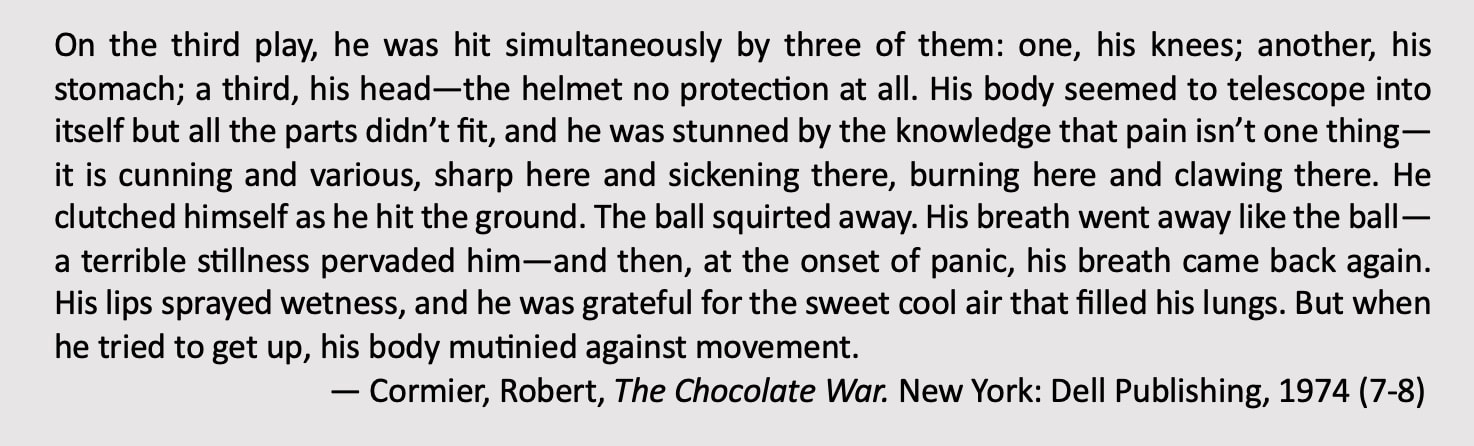

SENTENCE FLUENCY MENTOR TEXTS: use any well-written picture book or free-verse poem (read aloud to choose). I have used Robert Burleigh’s picture book, Home Run, and, with adolescent writers, an excerpt from The Chocolate Wars by Robert Cromier:

SENTENCE FLUENCY PROBLEMS

SENTENCE FLUENCY SOLUTIONS

COMBINING SENTENCES:

2. Using appositives to combine sentences: An appositive is a noun, noun phrase, or noun clause which follows a noun or pronoun and renames or describes the noun or pronoun.

Examples:

Jake is my dog. He likes to eat carrots. We give him carrots as a treat

Example: My dog Jake likes to eat carrots which we give him as a treat.

VARYING SENTENCE STRUCTURES

VARY SENTENCE BEGINNINGS. If too many sentences begin in the same way, the writing will be choppy and boring to read.

VARY SENTENCE LENGTHS

IMITATING SENTENCES: While imitating sentence patterns, students become aware of structure, which supports their understanding of punctuation and promotes style awareness: word order, varied sentence lengths and parallel structure, for example.

- Sentences begin the same way

- Sentences are the same length

- Sentences are short and choppy

- Run-on sentences or rambling sentences

SENTENCE FLUENCY SOLUTIONS

- COMBINING SENTENCES: Combine two or three short sentences into one.

- VARYING SENTENCE STRUCTURES: Change beginnings and sentence lengths.

- IMITATING SENTENCES: Examine good writing, and mimic the writer's style.

- Auditory trait: Have writers read writings aloud.

COMBINING SENTENCES:

- Combine multiple sentences into one:

- I have some homework. It is very difficult. Example: I have some difficult homework.

- I walked home from school. I passed two construction sites and a big crack in the sidewalk. It was pretty dangerous. Example: My walk home was pretty dangerous because I passed two construction sites and a big crack in the sidewalk.

- We went to the movies. We sat in the first row of the balcony. We ate a lot of popcorn. The movie was good. Example: We went to a movie and, sitting in the first balcony row, we ate popcorn while watching the movie which was very good.

2. Using appositives to combine sentences: An appositive is a noun, noun phrase, or noun clause which follows a noun or pronoun and renames or describes the noun or pronoun.

Examples:

- Mrs. Roessing, the ELA teacher, discussed the novel the class was reading.

- One of the students, Patty Finch, brought up some interesting questions about the characters.

- Another student, who had read the novel previously, was able to add his insights on the main character, Will Anderson.

Jake is my dog. He likes to eat carrots. We give him carrots as a treat

Example: My dog Jake likes to eat carrots which we give him as a treat.

VARYING SENTENCE STRUCTURES

VARY SENTENCE BEGINNINGS. If too many sentences begin in the same way, the writing will be choppy and boring to read.

- Begin a sentence with a prepositional phrase: Across the street construction was beginning on a new house.

- Add a second prepositional phrase at the beginning of the sentence: Across the street near the playground, construction was beginning on a new house.

- Even add a third prepositional phrase at the beginning of the sentence: Across the street near the playground of the school, construction was beginning on a new house.

- A mentor example: On the pleasant shore of the French Riviera, about halfway between Marseilles and the Italian border, stands a large, proud, rose-colored hotel.--F. Scott Fitzgerald, Tender Is the Night

VARY SENTENCE LENGTHS

- Include short sentences, mid-length sentences, and long, complex sentences

- Mentor Example: It wasn’t as if I didn’t want to work. I did. I had even gone to the social security office the month before to get my social security number. I needed money. The Catholic high school cost a lot, and Papa said nobody went to public school unless you wanted to turn out bad. —Sandra Cisneros, The House on Mango Street

- See Provost "Make music" quote at the beginning.

IMITATING SENTENCES: While imitating sentence patterns, students become aware of structure, which supports their understanding of punctuation and promotes style awareness: word order, varied sentence lengths and parallel structure, for example.

PURPOSEFUL RULE BREAKING: Break "rules" for effect, i.e., fragments. Conventions exist to aid comprehension of the writers' words and sometimes writers break them to convey their meaning.

Note: I always asked writers to mark (PF = purposeful fragment) so I knew that they knew they had written a fragment and did it for a reason.

Mentor Text Examples from Spinelli, Eileen. Someday. New York: Dial Books, 2007.

Someday I will be invited to the White House to have lunch with the President. He will want my ideas on world peace. I will wear white gloves and a hat with a new rose pinned to it. I will bring the President a box of golf balls. The White House waiter will pour tea. I will eat my salad carefully. No spills on the rug.

Today I am off to help my dad pain the shed. Green. [See the difference if it was written "Today I am off to help my dad pain the shed green.]

Note: I always asked writers to mark (PF = purposeful fragment) so I knew that they knew they had written a fragment and did it for a reason.

Mentor Text Examples from Spinelli, Eileen. Someday. New York: Dial Books, 2007.

Someday I will be invited to the White House to have lunch with the President. He will want my ideas on world peace. I will wear white gloves and a hat with a new rose pinned to it. I will bring the President a box of golf balls. The White House waiter will pour tea. I will eat my salad carefully. No spills on the rug.

Today I am off to help my dad pain the shed. Green. [See the difference if it was written "Today I am off to help my dad pain the shed green.]

--------------------------------------------

PUTTING STRATEGIES INTO PRACTICE: DRAFT REVISION

• READING ASSIGNMENT—Guided Practice:

• WRITING ASSIGNMENT—Guided Practice:

In pairs, rewrite the following passage varying the sentence structure.

Example: Janet went swimming. The pool was down the street. All of her friends were there. It was a hot afternoon. Janet did not know how to swim. She stayed in the shallow end. Sally and Debby felt sorry for Janet. They played in the shallow end with her. They were best friends. Some people called them “The Three Musketeers.”

• WRITING ASSIGNMENT—Independent Application:

Ask writers to return to the draft s they are revising and analyze at their sentences. Are they varied in length, in beginnings,

in structure?

Have them revise some of the sentences to provide more fluency. [Show your Teacher Model as an example]

They may want to read their drafts aloud (to themselves).

Note: Teach through the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model: one "solution" for each writing draft, build strategies and options. By the second draft writers will have two strategies/options, after the third, they will have three, etc.

PUTTING STRATEGIES INTO PRACTICE: DRAFT REVISION

• READING ASSIGNMENT—Guided Practice:

- In pairs look at the sentences in Owl Moon (or another well-written picture book).

- Look at sentence beginnings. Are they varied? In what ways? [

- Are the sentence structures varied? In what ways? Even if writers haven't learned the terms for "compound," "complex," or "compound-complex," they can describe how sentences are different and provide a musical effect.]

- simple

- simple with compound features (subjects; verbs)

- simple with prepositional or participial phrases

- compound

- complex

- compound-complex

• WRITING ASSIGNMENT—Guided Practice:

In pairs, rewrite the following passage varying the sentence structure.

Example: Janet went swimming. The pool was down the street. All of her friends were there. It was a hot afternoon. Janet did not know how to swim. She stayed in the shallow end. Sally and Debby felt sorry for Janet. They played in the shallow end with her. They were best friends. Some people called them “The Three Musketeers.”

• WRITING ASSIGNMENT—Independent Application:

Ask writers to return to the draft s they are revising and analyze at their sentences. Are they varied in length, in beginnings,

in structure?

Have them revise some of the sentences to provide more fluency. [Show your Teacher Model as an example]

They may want to read their drafts aloud (to themselves).

Note: Teach through the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model: one "solution" for each writing draft, build strategies and options. By the second draft writers will have two strategies/options, after the third, they will have three, etc.

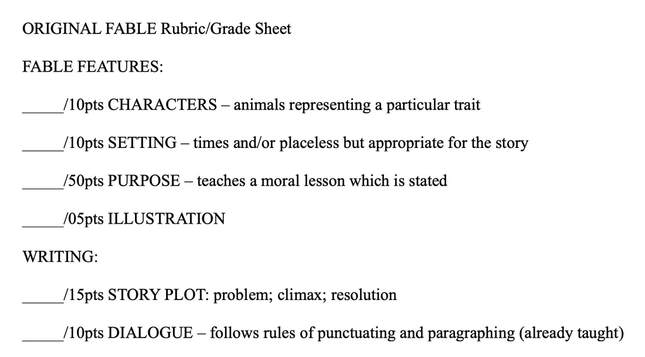

21. WRITING FABLES

FABLES are short stories that teach a moral lesson. Fables often feature characters that are animals, chosen to represent a particular character trait, i.e. a fox = cunning; pig = gluttony; ant = industriousness; coyote = prankster

The Lesson:

- I introduce students to Aesop, a writer who lived about 600 B.C. and wrote fables as political and social criticism.

- Teacher Model: I read or retell a well-known fable, such as "The tortoise and the Hare" and analyze the story elements and the characters and discuss what I think would be the moral/lesson and why (text evidence)

- Guided Practice: In pairs or triads the students read 1-2 fables and discern and discuss the moral lesson and how the story led readers to that moral.

- I read a more contemporary fable from James Thurber's Fables for Our Times (Harper Collins, 1983), and we analyze. I have found some modern fables: "A February Fable" in Writing! magazine (February 1988) and "Uncle Mike's Fables" in Literary Cavalcade (May 1988).

- Individually the students write a fable. The rubric* contains the fable elements we discussed and story elements we had already learned. For less proficient or confident writers, I provide a list of "morals" or quotes that contain moral lessons, and writer can choose one and write their fable to match.

A.J., one of my creative students wrote his fable in the form of a rhyming poem:

There once was a frog

Who lived in a bog

Just outside of Paradise City.

A place where you'd go

To hear the wind blow

Because even the wind sounded pretty.

This frog's name was Ted,

And I think someone said,

"That guy is really f-a-t!"

Once he woke up screaming

Because he'd been dreaming

He squashed his mother when he sat!

Other guys would get wise

And talk about Ted's size

And say, "Why are you so fat?"

Ted replied, "My life is for ME,

Not a sight for you to see.

Now, go away before I make you all FLAT!"

MORAL: "My life is for itself and not for a spectacle." --Ralph Waldo Emerson

20. COLLABORATIVE INFORMATIONAL WRITING: The Novel/Text Newspaper

PROJECT: In groups of 4 students will create a newspaper based on a novel (in ELA) or text (in Disciplinary Content Classes)

Teaching:

1. Using newspapers as mentor texts, the teacher teaches the content different types of ARTICLES in a newspaper, such as

1. Using newspapers as mentor texts, the teacher teaches the content different types of ARTICLES in a newspaper, such as

- National News articles

- Local News articles

- Feature/Human Interest stories

- Police Reports

- Advice Columns

- Obituaries

- Editorials or Commentaries

- Classified Ads

- Political Cartoons

- Sports News articles

2. Using newspapers as a mentor texts, Students study the layout of newspapers and of articles and such elements as placement of articles, by-lines, photo credits, etc.

For the project,

1. Students divide themselves into News Staffs (4/Staff)

2. Each Staff of responsible for a 2-page newspaper

• containing at least 4 different types of articles

• based on the world of the novel or disciplinary unit, plus any research conducted

1. Students divide themselves into News Staffs (4/Staff)

2. Each Staff of responsible for a 2-page newspaper

• containing at least 4 different types of articles

• based on the world of the novel or disciplinary unit, plus any research conducted

Guidelines/Directions:

- No novel/text facts may be altered or ignored. In the case of writing about a novel, Readers/Writers can make up anything not covered that is consistent with the novel. Anything added to a content area unit must be factual and based on research.

- Each article must follow the format of a particular type of article as modeled in an actual newspaper—students are to check their handouts and notes—and contain the by-line of the writer.

- Each Staff member is responsible for drafting one article; all articles are to be different types. At least 3 of the articles must be “factual” (local news, national news, human interest, police report, and/or obituary) and at least 1 must be an “opinion” article (“political” cartoon, advice column, book/text chapter review, people poll based on a thoughtful question presented to real people, editorial commentary, and/or a set of 3 classified ads).

*Any article that is research-based will earn extra credit; sources must be cited. Teacher can discuss topics that would be appropriate for your novel or unit. - Proofreading, revising, editing, fact checking, and layout are accomplished with the collaborative assistance of all Staff members.

- Any other jobs and decisions or extra articles or segments are divided among the Staff or accomplished collaboratively.

- The newspaper must be word-processed and properly formatted as a front page and second page, in 2 justified columns, completely filled in (no “white space” except 1/2” margins and a center margin).

Assessment:

The newspaper is assessed on

• format of newspaper and individual articles

• content - amount and accuracy of novel/text facts

• organization of individual articles and layout

• creativity

• conventions

50% of the grade earned is individual and based on the student's article and 50% of the grade is based from a group grade.

The newspaper is assessed on

• format of newspaper and individual articles

• content - amount and accuracy of novel/text facts

• organization of individual articles and layout

• creativity

• conventions

50% of the grade earned is individual and based on the student's article and 50% of the grade is based from a group grade.

Benefits of Project:

- Readers return to the text for more synthesis. See "The Benefits of After-Reading Response.)

- Students become more-critical readers of newspapers.

- Journalism writing.

- Group work provides instant and increased feedback and a sense of audience - elements often missing from the writing experience.

- The reactions of their peers help student writers understand they are writing for a community of readers, not only for a teacher.

- It reflects real-world writing situations where professionals often collaborate on presentations, reports, and projects.

- The project has both independent and interdependent components and meets multiple reading and writing standards.

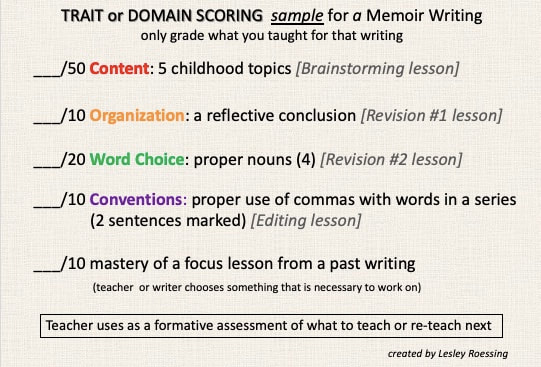

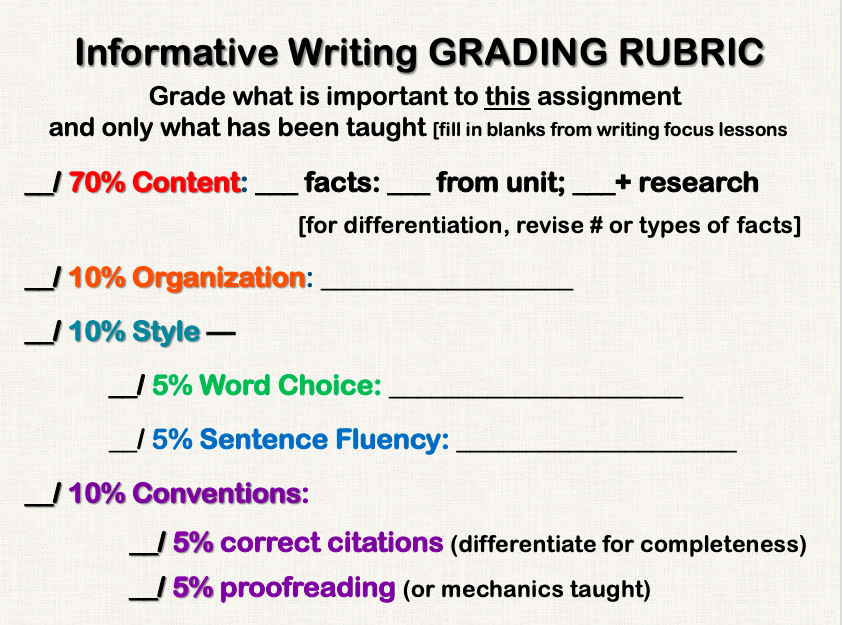

19. ASSESSING WRITING with Domain/Trait Rubrics

WRITING ASSESSMENT—RUBRICS that lead to improved writing:

For each writing—narrative, memoir, informative, argument, I taught 4 Focus Lessons (1 Trait or Domain per Writing Workshop):

see Strategy #15 below.

Then I only graded for what I had taught.

Writers had a copy of the rubric in advance with the blanks (shown on the Informational Writing and Memoir Writing rubrics pictured) filled in with the actual sub-Trait lesson. For example our Organization lesson for that writing could be a Surprising-Fact Lead or a Summary Conclusion or 4 transition words (highlighted) to connect ideas.

For each writing—narrative, memoir, informative, argument, I taught 4 Focus Lessons (1 Trait or Domain per Writing Workshop):

see Strategy #15 below.

Then I only graded for what I had taught.

Writers had a copy of the rubric in advance with the blanks (shown on the Informational Writing and Memoir Writing rubrics pictured) filled in with the actual sub-Trait lesson. For example our Organization lesson for that writing could be a Surprising-Fact Lead or a Summary Conclusion or 4 transition words (highlighted) to connect ideas.

Pictured are examples. Points could change and Trait-lessons did change for each writing.

After the beginning of the year, I added the 10 points for working on a past lesson that was not mastered [see sample Memoir Rubric] further into the year.

•When the students received their papers back and the rubric assessment, they were invited to use my feedback to rewrite for a new grade. I did not write on their papers, only on the rubric.

•This rubric also provided me with feedback about what lessons I needed to re-teach—to the entire class, to a small group, or individually during conferencing

•Contrast with the "typical" 4 or 5-pt rubric which is somewhat vague, using words like "adequate …," "attempts …," "some evidence of…," "writing lacks variety in …." My writers didn’t find these effective in helping to improve their writing.

Since we wrote a lot of short writings, writers added a lot of tools to their "toolbelts,” one writing at a time.

After the beginning of the year, I added the 10 points for working on a past lesson that was not mastered [see sample Memoir Rubric] further into the year.

•When the students received their papers back and the rubric assessment, they were invited to use my feedback to rewrite for a new grade. I did not write on their papers, only on the rubric.

•This rubric also provided me with feedback about what lessons I needed to re-teach—to the entire class, to a small group, or individually during conferencing

•Contrast with the "typical" 4 or 5-pt rubric which is somewhat vague, using words like "adequate …," "attempts …," "some evidence of…," "writing lacks variety in …." My writers didn’t find these effective in helping to improve their writing.

Since we wrote a lot of short writings, writers added a lot of tools to their "toolbelts,” one writing at a time.

18. FORMATTING INFORMATIVE WRITING: A-B-C BOOKS

Informative writing need not be written as an essay. Information can be formatted in diverse ways, as it is in the real world where information is shared through brochures, pamphlets, magazine and news articles, reports, a guide book, instructional manual, nonfiction books, etc. Each requires a different type of writing and formatting.

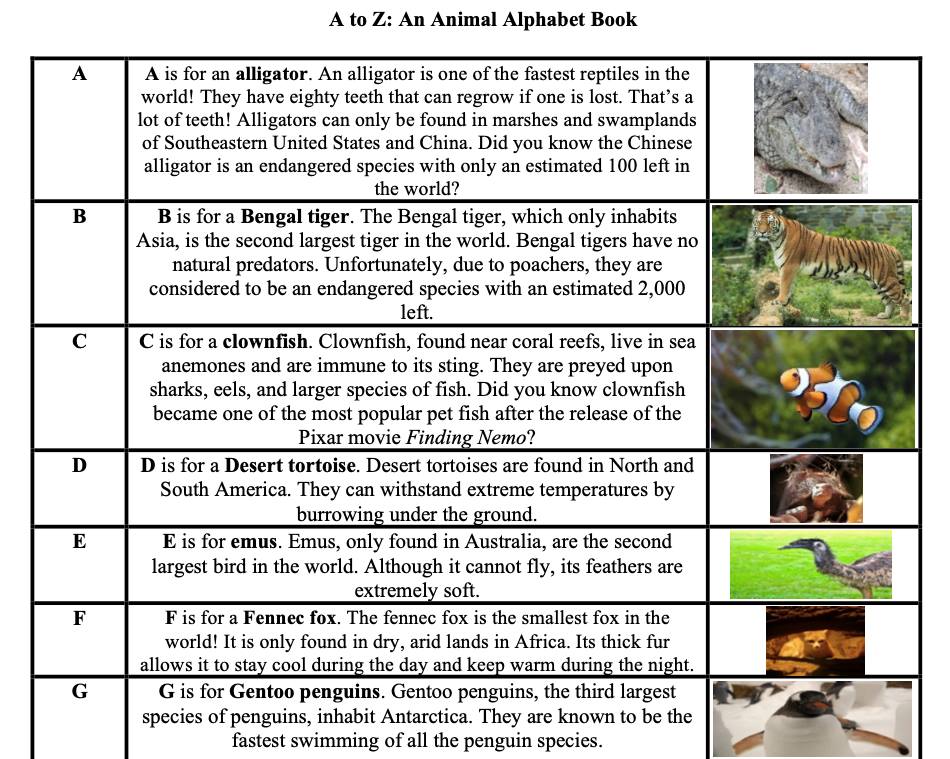

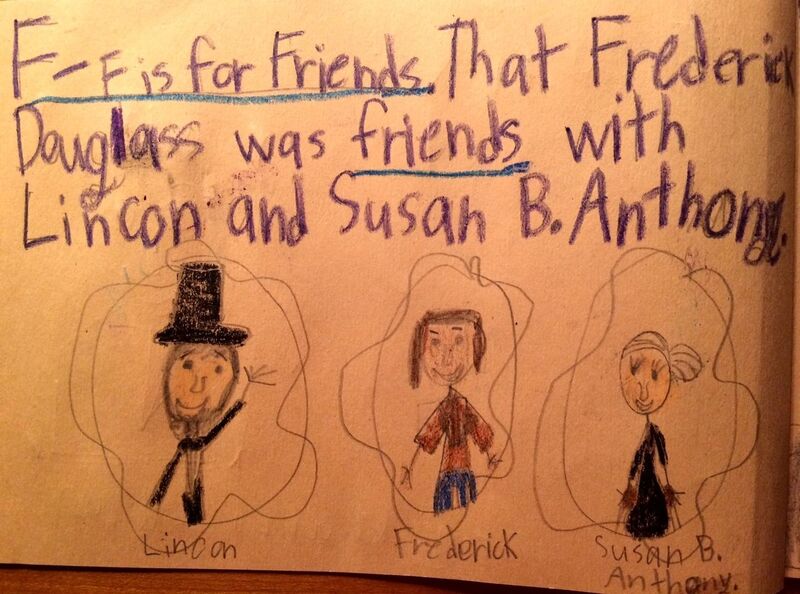

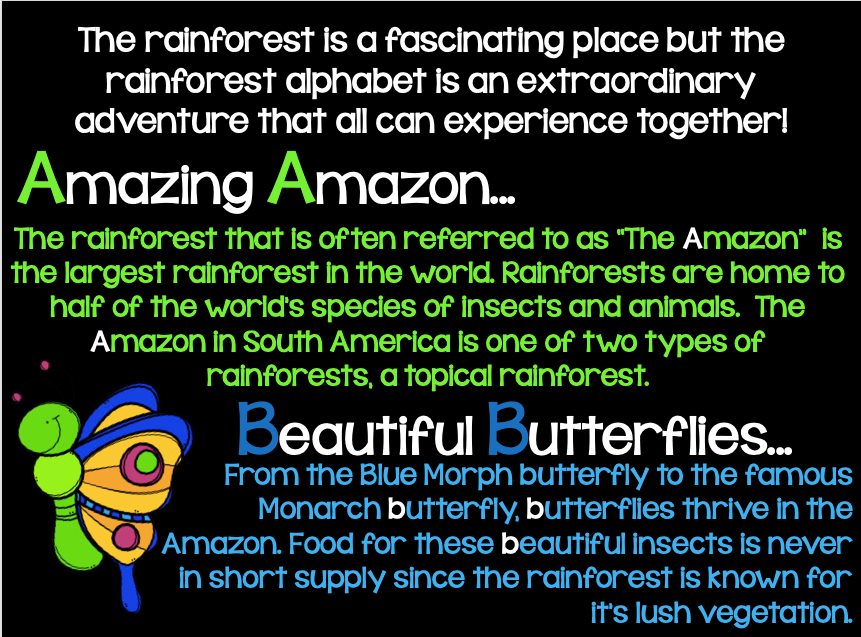

Here is one way to stretch research skills and write for an intended, authentic audience, such as classmates who need background information for a unit or before reading a novel or for a class of possibly younger students—creating an A-B-C book or chart.

Informative writing need not be written as an essay. Information can be formatted in diverse ways, as it is in the real world where information is shared through brochures, pamphlets, magazine and news articles, reports, a guide book, instructional manual, nonfiction books, etc. Each requires a different type of writing and formatting.

Here is one way to stretch research skills and write for an intended, authentic audience, such as classmates who need background information for a unit or before reading a novel or for a class of possibly younger students—creating an A-B-C book or chart.

- Begin with reading mentor texts written in the format (Sleeping Bear Press has A-B-C books on every topic):

- Individually or in pairs or small groups, students can write an A-B-C book for their peers or younger or less knowledgeable readers. More advanced students wrote A though Z based on their readings and research, others divided the alphabet among their small groups (A-H, I-P, and Q-Z), and a 3rd grade classroom wrote using the letters of their subject's name, reading 2-3 short biographical source books. When students collaborate in small groups, they can serve as peer editors for each other.

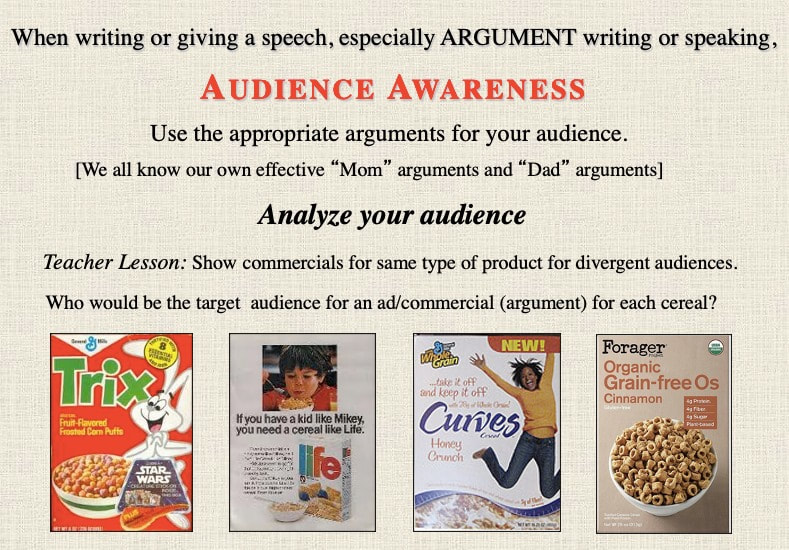

17. AUDIENCE AWARENESS FOR ARGUMENTATION

Audience awareness is a crucial strategy for writing and speeches, especially in argumentation and debate. Writers need to learn to analyze their expected audience and employ the techniques and evidence that will appeal to the specific audiences they are addressing.

This is a short activity I used with writers. I also was able to tape some commercials for like products that were tailored to different audience, such as a commercial for visiting Boston for tourists highlighting the famous tourist sites and a 1-800 phone number versus a commercial for Philadelphia for locals featuring the Academy of Music and mid-week deals on restaurants and a local area code phone number for information. I also employed a commercial for coffee aimed at tea drinkers (a Queen Elizabeth look-alike and a grandfather clock chiming High Tea time) and a commercial for milk aimed at teens. Students analyzed the arguments and how they would appeal to and persuade the targeted audiences.

Audience awareness is a crucial strategy for writing and speeches, especially in argumentation and debate. Writers need to learn to analyze their expected audience and employ the techniques and evidence that will appeal to the specific audiences they are addressing.

This is a short activity I used with writers. I also was able to tape some commercials for like products that were tailored to different audience, such as a commercial for visiting Boston for tourists highlighting the famous tourist sites and a 1-800 phone number versus a commercial for Philadelphia for locals featuring the Academy of Music and mid-week deals on restaurants and a local area code phone number for information. I also employed a commercial for coffee aimed at tea drinkers (a Queen Elizabeth look-alike and a grandfather clock chiming High Tea time) and a commercial for milk aimed at teens. Students analyzed the arguments and how they would appeal to and persuade the targeted audiences.

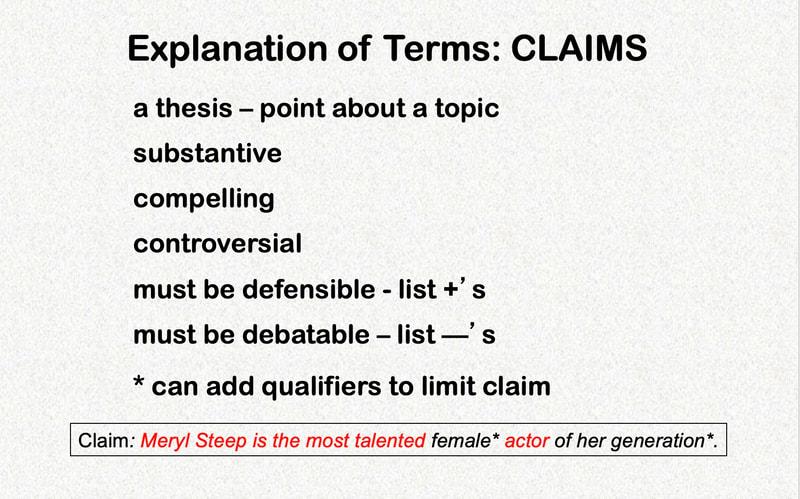

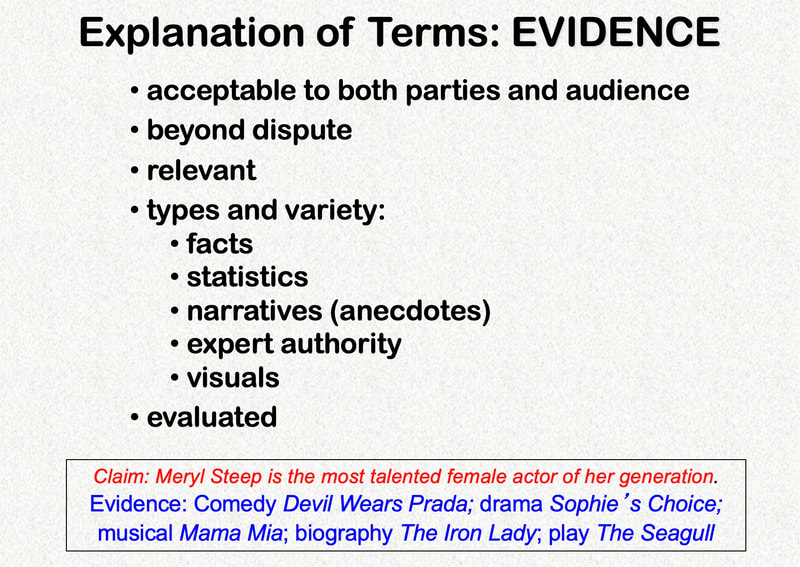

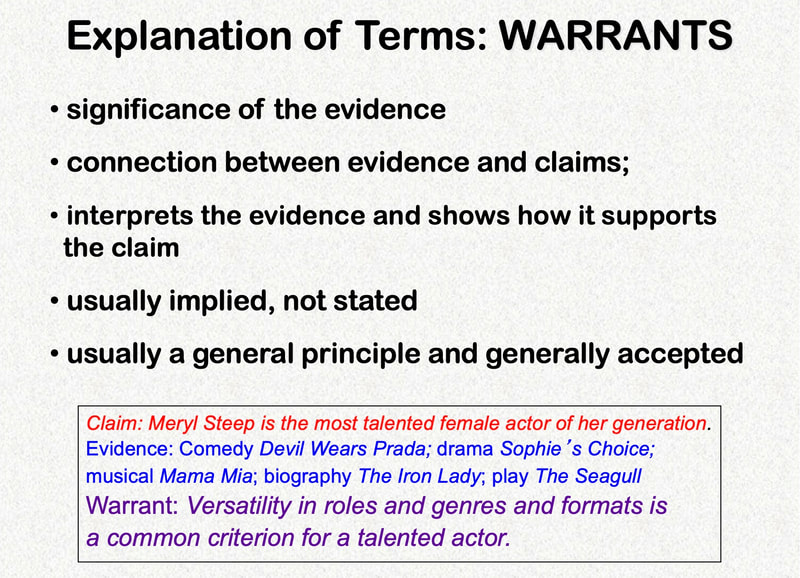

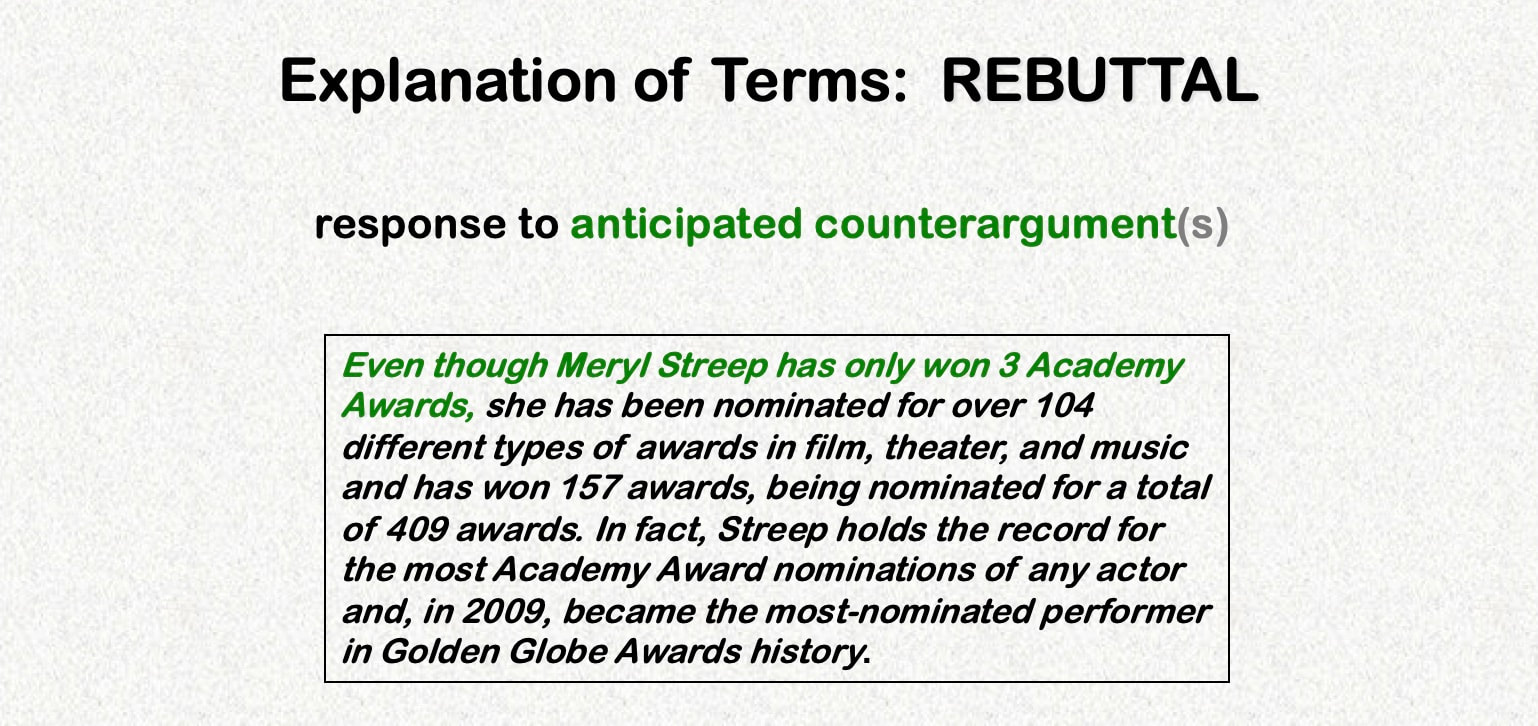

16. THE BASIC ELEMENTS OF ARGUMENT WRITING, explained

For students, I compare the WARRANT as when requesting a search warrant, it is the reason given to the judge to allow someone to collect evidence to support law enforcement's claim.

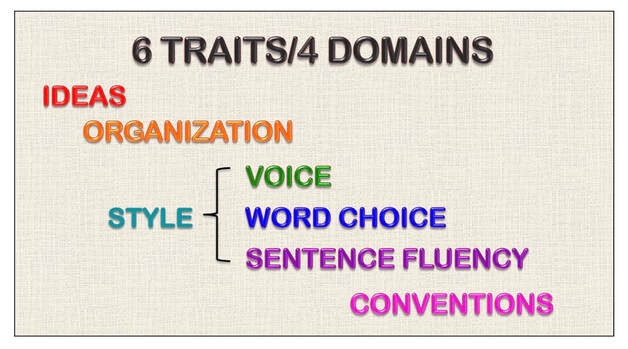

15. THE SIX TRAITS OF WRITING

The traits (or sometimes referred to as "domains") of writing provide the common vocabulary that writers use as they work to create interesting and well-written texts. Teaching through the 6 traits of writing provides focus lessons to help writers draft, revise, and edit their writings.

Each Trait Quality (and sub-qualities) provide individual lessons. As I wrote in my blog "The Steps & Strategies of Teaching a Writing," I teach one lesson (one element) for each writing domain or trait for each writing as students draft (Ideas), revise multiple times (Organization; 1 Style element), and finally edit (Conventions) before writing final publication (see Step #8).

Teach step-by-step through the writing process.

What are the TRAITS?

1. IDEAS are the main message, the content of the piece, the main theme, together with all the supporting details that enrich and develop that theme.

Trait Qualities:

2. ORGANIZATION is the internal structure of a piece of writing, the central meaning, the pattern and sequence.

Trait Qualities:

leads, introductions, and conclusions

transitions – words, phrases, sentences

pacing

patterns/structures:

THE STYLE TRAITS: VOICE, WORD CHOICE, and SENTENCE FLUENCY

3. VOICE is the writer's personal tone and "flavor," the sense that a real person is speaking to us and cares about the message.

Trait Qualities:

Trait Qualities:

Trait Qualities:

6. CONVENTIONS Trait is the mechanical correctness of the piece – accomplished through editing.

Conventions is the only trait with specific grade-level accommodations, and expectations should be based on grade level to include only those skills that have been taught.

Trait Qualities:

Each Trait Quality (and sub-qualities) provide individual lessons. As I wrote in my blog "The Steps & Strategies of Teaching a Writing," I teach one lesson (one element) for each writing domain or trait for each writing as students draft (Ideas), revise multiple times (Organization; 1 Style element), and finally edit (Conventions) before writing final publication (see Step #8).

Teach step-by-step through the writing process.

What are the TRAITS?

1. IDEAS are the main message, the content of the piece, the main theme, together with all the supporting details that enrich and develop that theme.

Trait Qualities:

- topic - main idea

- focus

- development

- details: quantity, quality, variety, accuracy, currency, reliability

2. ORGANIZATION is the internal structure of a piece of writing, the central meaning, the pattern and sequence.

Trait Qualities:

leads, introductions, and conclusions

transitions – words, phrases, sentences

pacing

patterns/structures:

- chronological or sequence

- description: spatial or importance

- compare/contrast

- problem/solution – question/answer

- cause/effect

THE STYLE TRAITS: VOICE, WORD CHOICE, and SENTENCE FLUENCY

3. VOICE is the writer's personal tone and "flavor," the sense that a real person is speaking to us and cares about the message.

Trait Qualities:

- tone

- conveying purpose

- connection with audience

- taking risks

- point of view

- dialogue

Trait Qualities:

- striking words and phrase

- strong verbs

- descriptive adjectives (sparingly)

- specific and accurate words, i.e., proper nouns

- words that deepen meaning and make pictures

- disciplinary words

- lack of redundancy, wordiness, vagueness, clichés

- use modifiers sparingly – show, don’t tell about

Trait Qualities:

- Well-built sentences

- Variation in sentence types – simple, compound, complex, compound-complex,

- Variation in sentence lengths – compound subjects, compound predicates, phrases, clauses

- Variations in sentence beginnings

- Smooth and rhythmic “flow”

- Purposeful rule breaking for effect, i.e., fragments

6. CONVENTIONS Trait is the mechanical correctness of the piece – accomplished through editing.

Conventions is the only trait with specific grade-level accommodations, and expectations should be based on grade level to include only those skills that have been taught.

Trait Qualities:

- Punctuation

- Capitalization

- Spelling (proofreading)

- Applying grammar and usage rules

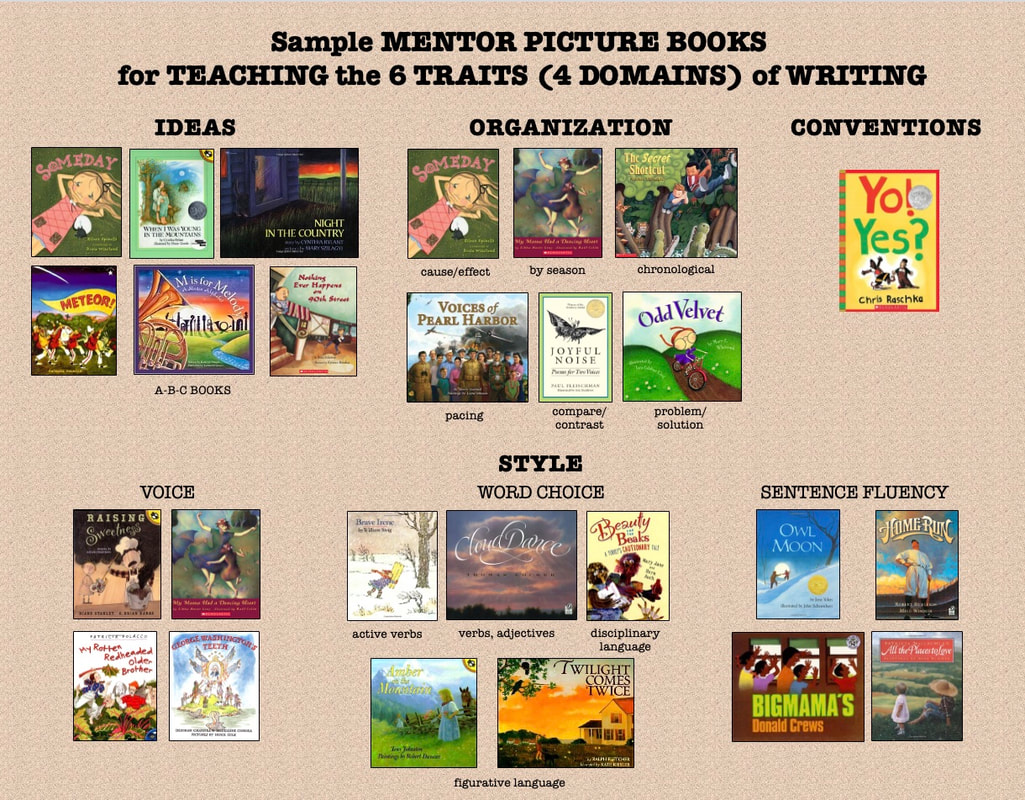

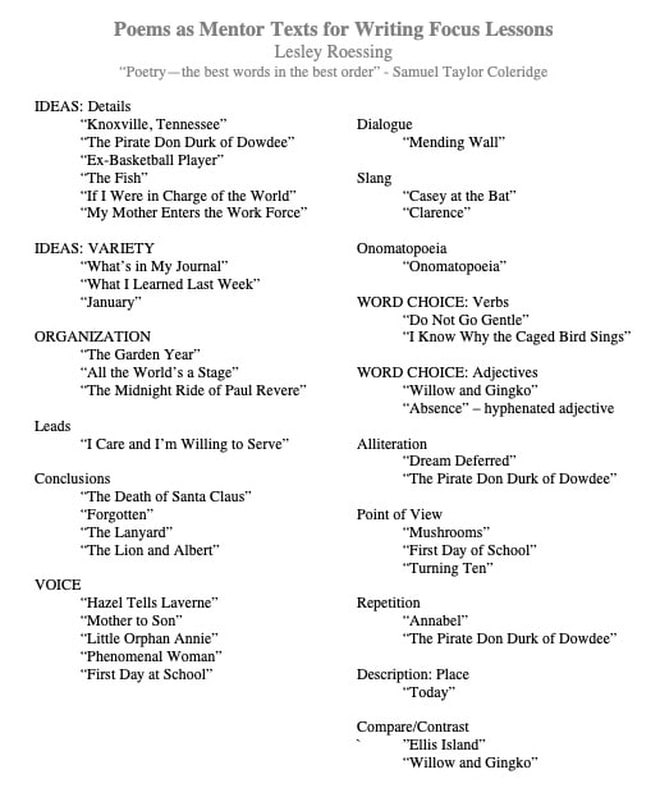

Using MENTOR TEXTS: especially picture books and poetry, novel excerpts, nonfiction excerpts, and articles.

Read multiple mentor texts to see how trait is handled, reading like a writer. Read for clues about the writer’s craft; every reading becomes a writing lesson. These are samples of picture books (above) and poems (below) that I have found effective for teaching a specific trait or, in some cases, multiple trait lessons.

My advice is to read through picture books (and poetry) and ask yourself

My advice is to read through picture books (and poetry) and ask yourself

- What do I notice about the writing

- What makes this writing work

- What makes this writing effective

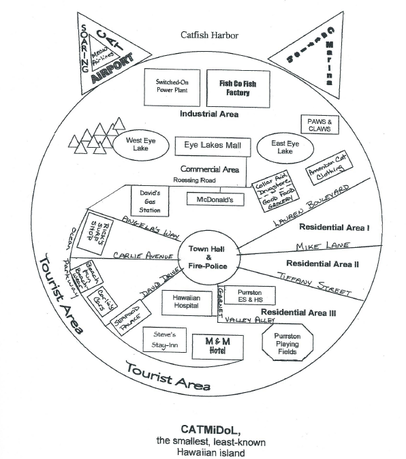

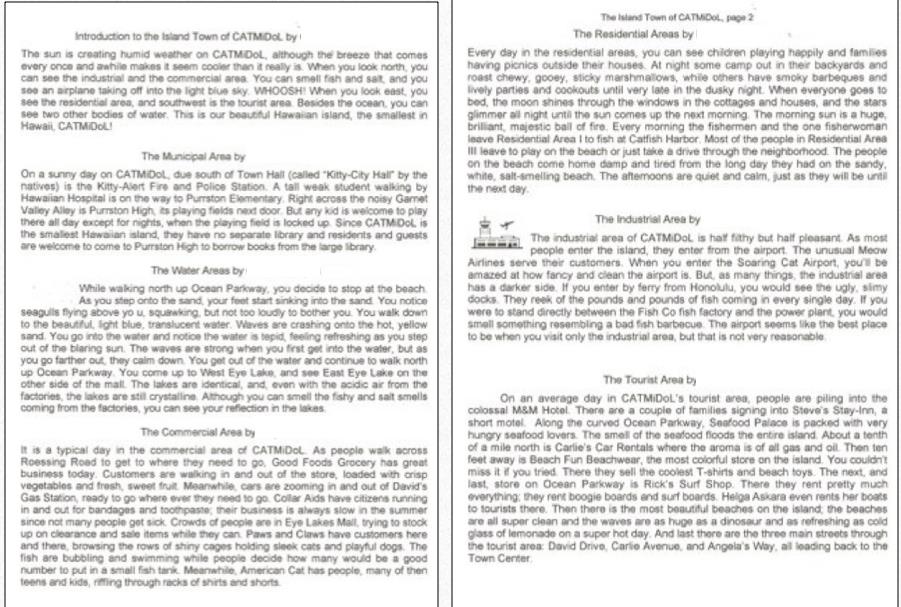

14. A COLLABORATIVE WRITING PROJECT THAT INCLUDES NARRATIVE, INFORMATIVE, AND PERSUASIVE WRITING

The Town Project combines narrative, informational, and persuasive (argument) writing, as well as collaboration, critical thinking, and interdisciplinary skills [and is the project my former students always mention when we reconnect]

The Town Project combines narrative, informational, and persuasive (argument) writing, as well as collaboration, critical thinking, and interdisciplinary skills [and is the project my former students always mention when we reconnect]

1. In small groups students collaboratively design a town with residential, commercial, and industrial areas and government agencies. (science/math/social studies/critical thinking)

2. Groups write short histories and descriptions of their towns (informational writing)

3. Groups create commercials or ads for their businesses (persuasive/argument writing)

4. Groups populate their towns brainstorming some of the more prominent residents

5. Individually, group members choose a citizen and write a short story featuring the character (narrative writing)

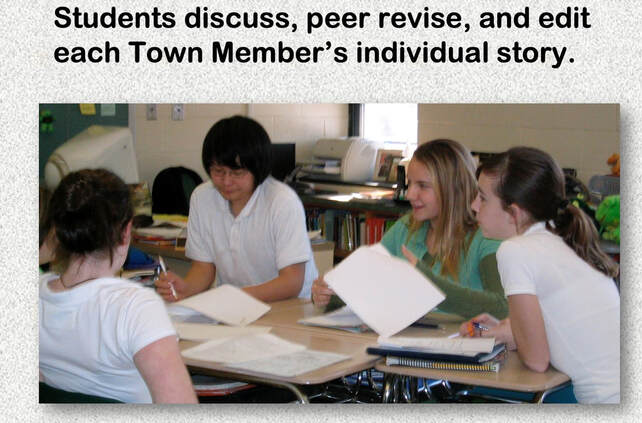

6. Students share their drafts with their Town for Peer Review (see Writing Strategy #10)

7.Revised, edited maps, Town Statistics, Histories and Descriptions, and stories are published in a class book, divided by Town for independent reading time.

2. Groups write short histories and descriptions of their towns (informational writing)

3. Groups create commercials or ads for their businesses (persuasive/argument writing)

4. Groups populate their towns brainstorming some of the more prominent residents

5. Individually, group members choose a citizen and write a short story featuring the character (narrative writing)

6. Students share their drafts with their Town for Peer Review (see Writing Strategy #10)

7.Revised, edited maps, Town Statistics, Histories and Descriptions, and stories are published in a class book, divided by Town for independent reading time.

The students who created CATMiDoL Island decided to combine their initials and then make their town an island in the shape of a cat's head. Listening to their brainstorming and decisions was fascinating. The right ear houses the fishing docks, as fishing and canning are the Town's industry; the left ear is the airport. They decided that the business district shouldn't take up the valuable beach property that could be used as for tourists, and they kept the tourists (and the wealthier homeowners in Residential Areas II and III) away from the smells of the fishing docks and the cannery. Lots of critical thinking and negotiating was going on. They decided that instead of one person writing the town description, they each would write about a section of their Town, and then they each wrote a short story about a Town citizen.

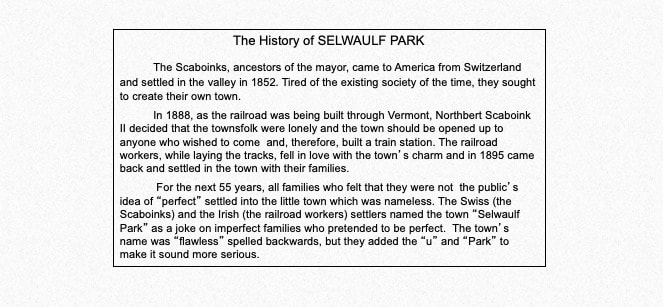

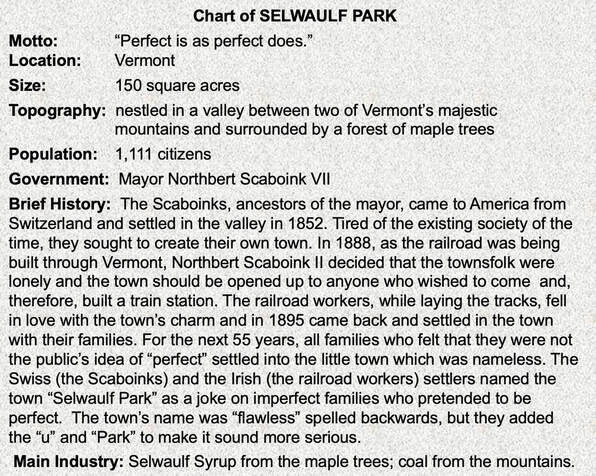

Sewaulf Park is another Town project described in No More "Us" and "Them." This was the 8th grade group's chart and history.

EXTENSION:

8. The students in each Town choose one of their Town stories to revise and turn into a script for a 20 minute radio show with sound effects and commercials to perform for the class.

------

See more details and expanded activities for the Town Project, such as the script writing to turn Town stories into a radio show, and meeting speaking standards, in No More "Us" and "Them": Classroom Lessons & Activities to Promote Peer Respect.

8. The students in each Town choose one of their Town stories to revise and turn into a script for a 20 minute radio show with sound effects and commercials to perform for the class.

------

See more details and expanded activities for the Town Project, such as the script writing to turn Town stories into a radio show, and meeting speaking standards, in No More "Us" and "Them": Classroom Lessons & Activities to Promote Peer Respect.

13. BRAINSTORMING SETTINGS FOR NARRATIVE WRITING

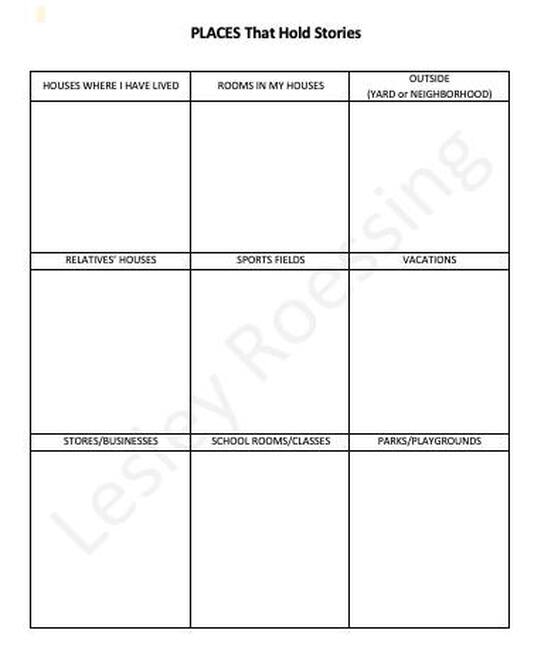

In keeping with "writing what we know," writers can brainstorm and gather ideas from places they have experienced to create settings and even plot ideas for narrative writings: fictional stories, personal narratives, memoirs, and descriptive writing (and, in some cases, informative writing) using a chart such as this. Writers can add to the chart throughout the year as ideas surface from texts read and class/group discussions about readings and other writings.

In keeping with "writing what we know," writers can brainstorm and gather ideas from places they have experienced to create settings and even plot ideas for narrative writings: fictional stories, personal narratives, memoirs, and descriptive writing (and, in some cases, informative writing) using a chart such as this. Writers can add to the chart throughout the year as ideas surface from texts read and class/group discussions about readings and other writings.

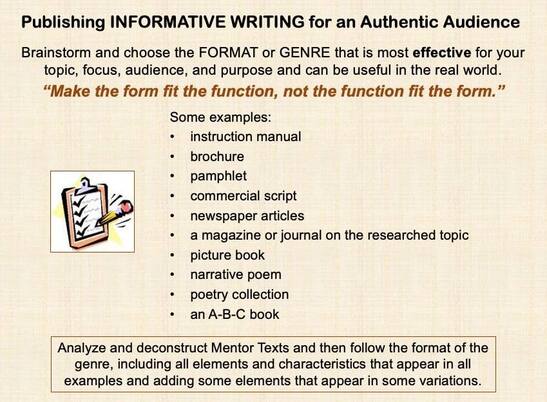

12. WRITING FOR AN AUTHENTIC AUDIENCE

When writers write for an authentic audience, I find that they tend to write better, research more, and acknowledge the importance of editing.

Suggestion: Follow the Steps for Informative Writing in Writing Strategies #6 and 7. Publishing is the final step to a formal writing. And see my Research Strategy #2 for examples of writing Informative Texts as picture books.

When choosing a format, students analyze mentor textss, not only for amount and type of content, but for format features such as font size, visuals—photos or drawings and percentage in relation to text; diagrams and charts; use of color; placement of facts; headings and subheadings; technical language; in brochures, # of columns; text structure; etc.

If they are writing for a younger audience (picture books), they need to think about word choice and vocabulary. If they are writing for an audience who is unfamiliar with topic, they need to make decisions about what explanations may be necessary.

Where I Get My Mentor Texts:

I gather brochures when at museums, historic venues, hotels, and even doctor offices and have found nutrition and exercise brochures at my gym.

I have employed pamphlets and instruction manuals from my purchased products and those I read when beginning a new sport.

News articles and topical journals and magazines such as Sports Illustrated and Tennis are easy to find.

Sleeping Bear Press has ABC books, as do other publishers.

I have used George Washington's Teeth as an example of an informative picture book and as a narrative informational poem.

I gathered commercial scripts from Garrison Keillor's Prairie Home Companion website, but students could viewcommercials and read ads from a variety of places to see how information is woven in.

Suggestion: Follow the Steps for Informative Writing in Writing Strategies #6 and 7. Publishing is the final step to a formal writing. And see my Research Strategy #2 for examples of writing Informative Texts as picture books.

When choosing a format, students analyze mentor textss, not only for amount and type of content, but for format features such as font size, visuals—photos or drawings and percentage in relation to text; diagrams and charts; use of color; placement of facts; headings and subheadings; technical language; in brochures, # of columns; text structure; etc.

If they are writing for a younger audience (picture books), they need to think about word choice and vocabulary. If they are writing for an audience who is unfamiliar with topic, they need to make decisions about what explanations may be necessary.

Where I Get My Mentor Texts:

I gather brochures when at museums, historic venues, hotels, and even doctor offices and have found nutrition and exercise brochures at my gym.

I have employed pamphlets and instruction manuals from my purchased products and those I read when beginning a new sport.

News articles and topical journals and magazines such as Sports Illustrated and Tennis are easy to find.

Sleeping Bear Press has ABC books, as do other publishers.

I have used George Washington's Teeth as an example of an informative picture book and as a narrative informational poem.

I gathered commercial scripts from Garrison Keillor's Prairie Home Companion website, but students could viewcommercials and read ads from a variety of places to see how information is woven in.

11. A GETTING-TO-KNOW-YOU "WRITING" ACTIVITY

This was my activity to help students (and teachers) to not only learn each others' names but to get to know each other (from No More "Us" & "Them": Classroom Lessons and Activities to Promote Peer Respect (review by writing expert Vicki Spandel)

Step 1: Brainstorm categories, i.e., favorite foods, books, sports, hobbies, pets, places, family, mementos,...

Step 2: Each student lists things they like in each category, something that tells about THEM.

Step 3: Students rough-sketch their letters—capital or small or mixture—into images that tell about them and their lives.

Step 4: They fold cardstock into a long tent, and draw letters and color.

Step 5: Students meet in small groups and, looking at each sign, discuss what they are learning about each other and what they all have in common.

For ELA classes, this activity also introduces the writing process: brainstorming, organizing, drafting, revising and editing.

After everyone knows each other, the signs can be kept in the classroom and brought out when substitutes or speakers are visiting the classroom. [Idea: In distance learning, could the camera focus on the name plate for those who wish not to appear on camera?]

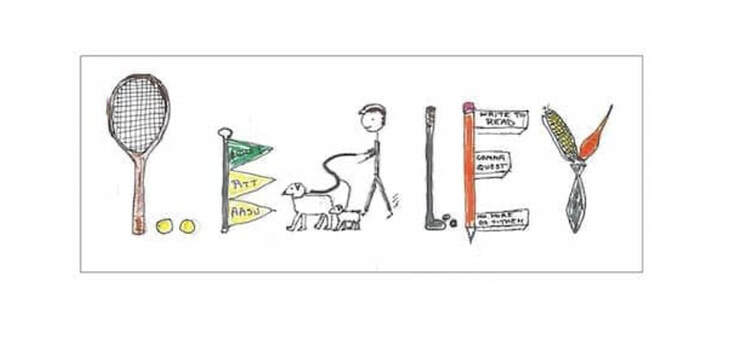

What do you learn about me from my name sign above? [I love tennis, schools attended and taught, my husband who runs with our 2 Aussies, I golf, the 3 books I wrote (at the time of the sign); I am a pescatarian.]

Note: An Informational writing-research assignment, my Names Project, is also included in No More "Us" and "Them." Students enjoyed researching their names and writing about them in different formats.

Step 1: Brainstorm categories, i.e., favorite foods, books, sports, hobbies, pets, places, family, mementos,...

Step 2: Each student lists things they like in each category, something that tells about THEM.

Step 3: Students rough-sketch their letters—capital or small or mixture—into images that tell about them and their lives.

Step 4: They fold cardstock into a long tent, and draw letters and color.

Step 5: Students meet in small groups and, looking at each sign, discuss what they are learning about each other and what they all have in common.

For ELA classes, this activity also introduces the writing process: brainstorming, organizing, drafting, revising and editing.

After everyone knows each other, the signs can be kept in the classroom and brought out when substitutes or speakers are visiting the classroom. [Idea: In distance learning, could the camera focus on the name plate for those who wish not to appear on camera?]

What do you learn about me from my name sign above? [I love tennis, schools attended and taught, my husband who runs with our 2 Aussies, I golf, the 3 books I wrote (at the time of the sign); I am a pescatarian.]

Note: An Informational writing-research assignment, my Names Project, is also included in No More "Us" and "Them." Students enjoyed researching their names and writing about them in different formats.

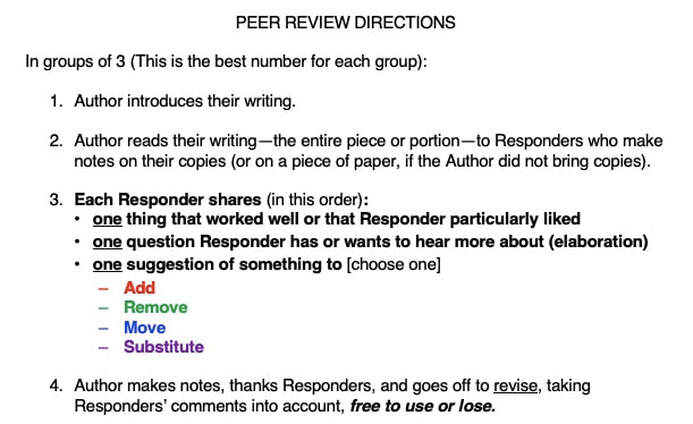

10. PEER REVIEW FOR REVISING A WRITING

An effective strategy for helping writers to revise their writings is feedback that "praises, prods, and polishes" by peer review. I have found the optimal number in a peer review group to be three—in each round is a writer and two reviewers—because the writer is not overwhelmed by too many suggestions.

An effective strategy for helping writers to revise their writings is feedback that "praises, prods, and polishes" by peer review. I have found the optimal number in a peer review group to be three—in each round is a writer and two reviewers—because the writer is not overwhelmed by too many suggestions.

Forming Peer Review (or "Peer Response") Groups:

I allowed my students to choose their groups for narrative and memoir writing which may be personal. For informative and argument writing I might form the groups, choosing students whose strengths and weakness as writers balance each other. By the time of the year that students are writing independent self-selected pieces (see my chart in Strategy #8 below), the peer review strategy has become so ingrained that a student might just ask, during Writing Workshop Independent Writing time, if there are two other students who are at the appropriate place in their writing process who can join for a peer review session.

I allowed my students to choose their groups for narrative and memoir writing which may be personal. For informative and argument writing I might form the groups, choosing students whose strengths and weakness as writers balance each other. By the time of the year that students are writing independent self-selected pieces (see my chart in Strategy #8 below), the peer review strategy has become so ingrained that a student might just ask, during Writing Workshop Independent Writing time, if there are two other students who are at the appropriate place in their writing process who can join for a peer review session.

Tips for Successful Reviews:

I have had students of all ages, from elementary to college writers, volunteer that peer review—done in this matter—was helpful and did not feel like they or their writing was being criticized. They especially liked that the writer could choose to use the suggestions or not but found that they usually did.

- Make sure that the peer writers review in the listed order.

- Praising what the writer does well is important because it leads to writers doing more of whatever worked well (and knowing what not to delete or change when revising)

- The writer does not respond to the reviewers. In Step #2 the reviewer is merely giving insight into how a reader may react. The writer simply notes the two readers' (listeners') comments and then can decide if they want to employ those suggestions or not. It is still the writer's writing.

- When introducing peer review, the teacher can read a short draft and fishbowl with two colleagues or two students. It is only necessary to show them responding to the teacher's writing; it is not necessary—for demonstration purposes—to read and respond to all three writings.

- During Student Peer Review, everyone takes a turn reading their writing and giving responses.

- Make sure reviews are specific:

- I liked your use of the senses when you wrote how the backyard in your new house, not only looked, but smelled "like cut grass" and sounded "like the birds constantly chirping at each other".

- As a reader I would like to know if this was the first time you had a big yard.

- I would suggest that you try moving your first paragraph further down in the writing because it would be interesting to see the yard before the reader hears about the neighborhood kids playing games. It would set the scene.

I have had students of all ages, from elementary to college writers, volunteer that peer review—done in this matter—was helpful and did not feel like they or their writing was being criticized. They especially liked that the writer could choose to use the suggestions or not but found that they usually did.

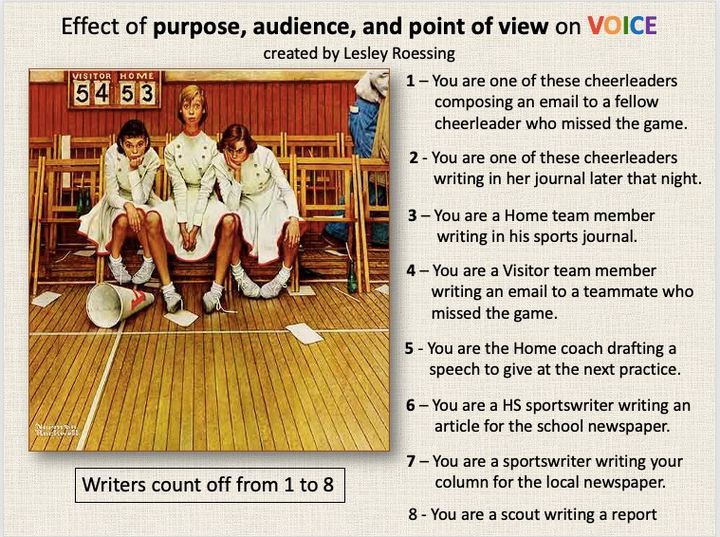

9. TEACHING VOICE IN WRITING

VOICE: one trait that elevates writing—and my strategy for teaching it.

VOICE: one trait that elevates writing—and my strategy for teaching it.

When writers share their drafts, they hear the different voices and can discuss how the audience, the format, and the writers' diverse perspectives and purposes influenced voice.

Rockwell, Norman. "Cheerleaders (Losing the Game)." Saturday Evening Post cover, Feb 16, 1952

Rockwell, Norman. "Cheerleaders (Losing the Game)." Saturday Evening Post cover, Feb 16, 1952

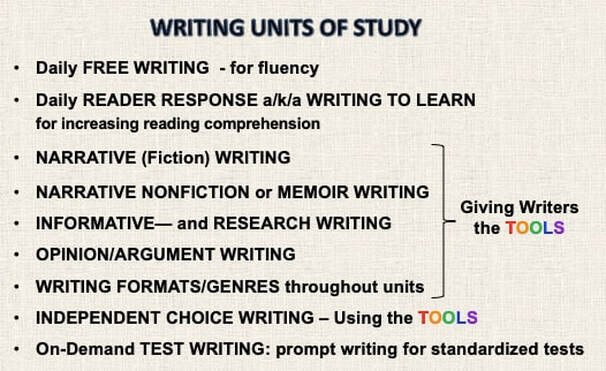

8. WRITING THROUGH THE YEAR

Teaching through the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model, moving from what writers know and/or what is familiar to what is new or more complex. This is how I scaffolded WRITING THROUGH THE YEAR.

Teaching through the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model, moving from what writers know and/or what is familiar to what is new or more complex. This is how I scaffolded WRITING THROUGH THE YEAR.

Free Writes (see Writing Strategy #1) were held every day (or teachers with shorter class periods can alternate days with Vocabulary), and Test Writing format (On-Demand Writing) was taught/reviewed one Friday/month (my Test Prep Days).

Daily Reader Response Writing a/k/a Writing to Learn was taught within Reading lessons, scaffolded through the year (see "The Importance of Reader Response").

Modes or types of writing were taught in order of complexity: Narrative > Memoir or Narrative Nonfiction > Informative Writing, adding Research > Opinion or Argument Writing, depending on the grade level. Within each mode of writing, Writing Workshop Focus Lessons are employed to teach the use of Trait or Domain qualities for that mode (i.e., Informative writing leads), and different formats can be taught within each mode, such as essays, stories, graphics, and a variety of types of poetry, all of which build the writer's toolbox. For an example with Informative Writing, see Writing Strategies #6-7.

At the end of the year (the last 4-9 weeks), writers were given the choice of topic, mode, and/or format in order to have a chance to use the tools to build writings. An analogy: first we teach builders how to use a saw and let them practice; then we teach them how to use a screwdriver and let them practice, and so on. Then they may decide for a project whether to use a saw or screwdriver or both. At some point we need to give them the independence to plan an entire building project and to select which tools they feel will be most effective and useful for that project—and at what point.

Note: Writings can be short and not all writings need to need to be taken to final publication.

Daily Reader Response Writing a/k/a Writing to Learn was taught within Reading lessons, scaffolded through the year (see "The Importance of Reader Response").

Modes or types of writing were taught in order of complexity: Narrative > Memoir or Narrative Nonfiction > Informative Writing, adding Research > Opinion or Argument Writing, depending on the grade level. Within each mode of writing, Writing Workshop Focus Lessons are employed to teach the use of Trait or Domain qualities for that mode (i.e., Informative writing leads), and different formats can be taught within each mode, such as essays, stories, graphics, and a variety of types of poetry, all of which build the writer's toolbox. For an example with Informative Writing, see Writing Strategies #6-7.

At the end of the year (the last 4-9 weeks), writers were given the choice of topic, mode, and/or format in order to have a chance to use the tools to build writings. An analogy: first we teach builders how to use a saw and let them practice; then we teach them how to use a screwdriver and let them practice, and so on. Then they may decide for a project whether to use a saw or screwdriver or both. At some point we need to give them the independence to plan an entire building project and to select which tools they feel will be most effective and useful for that project—and at what point.

Note: Writings can be short and not all writings need to need to be taken to final publication.

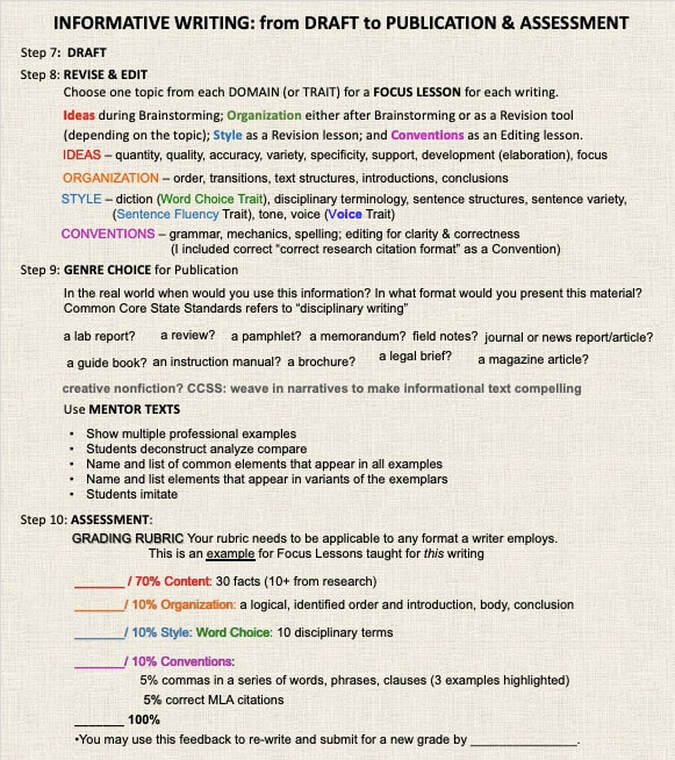

7. INFORMATIVE WRITING: From Draft to Publication & Assessment

Part 2 shares the last 4 steps and strategies for INFORMATIVE WRITING.

(For Steps 1-6, see Writing Strategy #6)

7. Students use their brainstorming and prewriting activities to DRAFT an informative essay.

8. For the REVISION and EDITING steps, the teacher chooses one lesson from each Domain or Writing Trait for a daily FOCUS LESSON.

10. Last, the teacher designs a RUBRIC that would equally ASSESS writings in any format, assessing only what was taught for that writing.

(For Steps 1-6, see Writing Strategy #6)

7. Students use their brainstorming and prewriting activities to DRAFT an informative essay.

8. For the REVISION and EDITING steps, the teacher chooses one lesson from each Domain or Writing Trait for a daily FOCUS LESSON.

- Lessons on IDEAS can be taught during prewriting;

- ORGANIZATION qualities that focus on the actual order or pacing of the writing can also provide a focus lesson during prewriting as writers organize their brainstorming.

- Other ORGANIZATION lessons, such as leads,conclusions, and transitions, can be taught in a revision lesson.

- One STYLE lesson, either WORD CHOICE, SENTENCE FLUENCY, or VOICE, is taught as a revision lesson.

- A CONVENTION lesson is taught during the editing stage.

10. Last, the teacher designs a RUBRIC that would equally ASSESS writings in any format, assessing only what was taught for that writing.

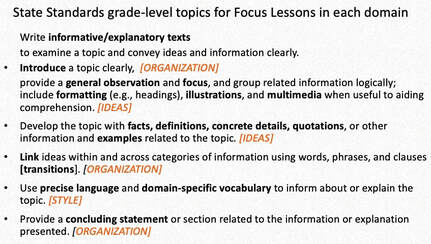

Typical State Standards to be met by Informative Writing and the domain lessons that address those standards:

Watch for my upcoming December BLOG on the "Steps & Strategies for Teaching Writing" in which I will take readers through a piece of writing through the writing process from mentor text to final publication, applicable to all writings.

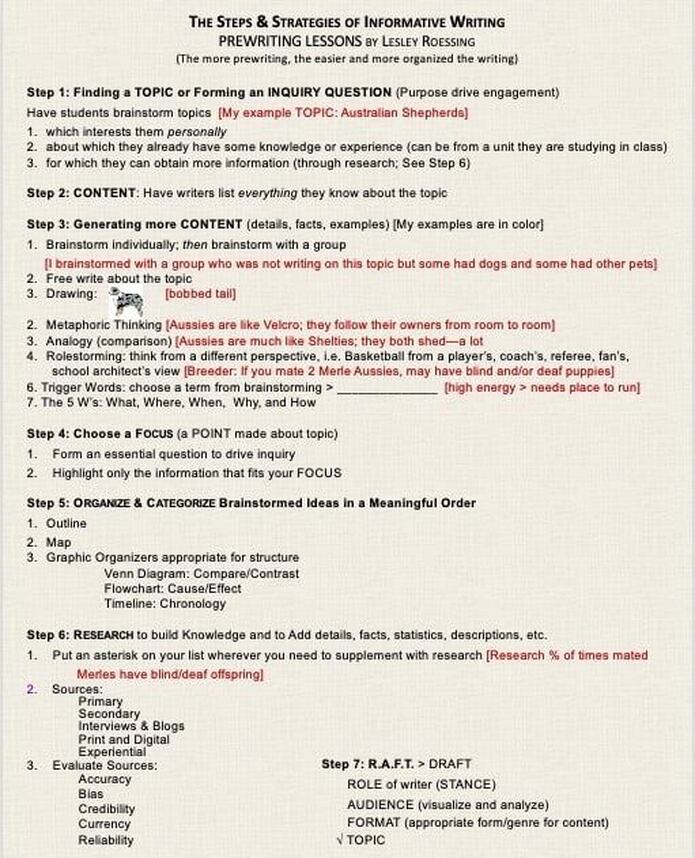

6. INFORMATIVE WRITING: PREWRITING STEPS & STRATEGIES

These are my first 6 steps and strategies for INFORMATIVE WRITING. I have found that the more time spent prewriting, the easier and more organized is the writing (and the faster the writing and revision go). I agree wholeheartedly (and my classroom experiences bear out) with writing expert Donald Graves. “Donald Graves discovered that the best writers rehearsed what they were going to write before they began."— Donald M. Murray, Pulitzer prize-winning journalist, in Writing to Deadline.

My first steps are for each student to brainstorm and discover a topic in which they have an interest and some prior knowledge or experience. generate as much content from what they already know, and use research techniques to verify and add to that knowledge. I then use each informative writing (which can be of any length and published in any format) to teach new writing and research skills, adding throughout the year.

My first steps are for each student to brainstorm and discover a topic in which they have an interest and some prior knowledge or experience. generate as much content from what they already know, and use research techniques to verify and add to that knowledge. I then use each informative writing (which can be of any length and published in any format) to teach new writing and research skills, adding throughout the year.

My next Writing Strategy post will add the next steps, beginning with Step #7 RAFT—determining the ROLE (or stance) of the writer, the target AUDIENCE, the FORMAT of the final piece, and the TOPIC of the writing which is many cases has been narrowed or expanded—moving to DRAFTing.

Watch for my next BLOG on the "Steps & Strategies for Teaching Writing" in which I will take readers through a piece of writing through the writing process from mentor text to final publication, applicable to all writings.

Watch for my next BLOG on the "Steps & Strategies for Teaching Writing" in which I will take readers through a piece of writing through the writing process from mentor text to final publication, applicable to all writings.

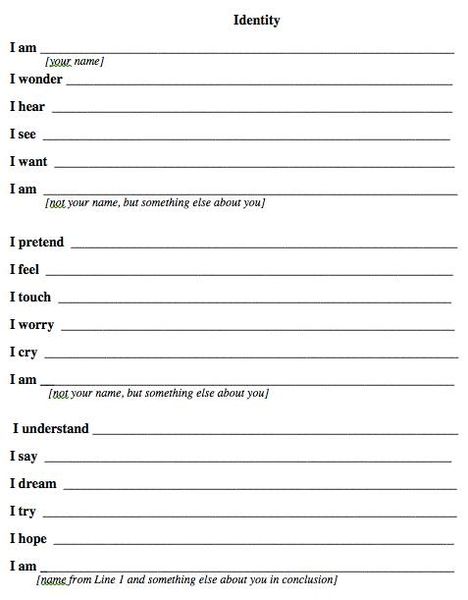

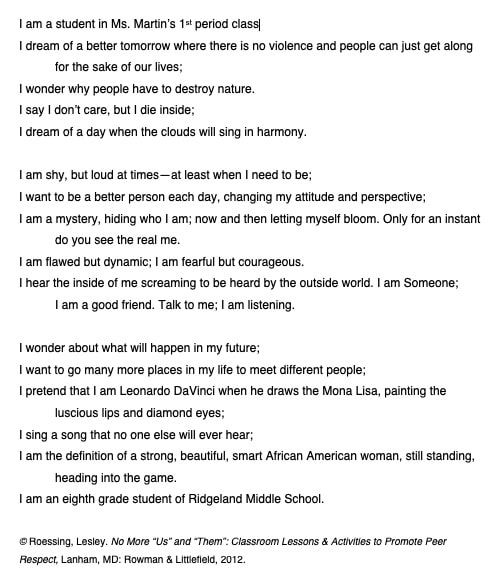

5. THE CLASS "WE ARE" POEM

- As an Identity poem, students write an I Am poem using the form to assist them with the format, including details and images and whatever poetic devices they have learned. Students may change verbs to one(s) they find more appropriate to describe themselves.

- Writers then each choose their favorite line of their poems and mark with an asterisk.

- Students stand in a circle around the room and, beginning with "We are Mr/Ms _______'s ____ period Language Arts class," each student then reads their favorite line. Verbs can be repeated by multiple class members.

- The class together ends with "I am an ____ grade student of _________ School."

4. WRITING A COLLABORATIVE STORY: A (Visual) Reading-Writing-Speaking Activity

- Divide students into groups of three.

- Each group chooses a picture.

- Writing Groups are to collaboratively draft a short story (characters, plot/problem, setting) with dialogue. Note: It is difficult NOT to create a story with a Rockwell picture or a Teenie Harris photograph (even for teacher-writers; see photo below).

- Each group can then present their story in Readers' Theater format with a narrator

Benefits of COLLABORATIVE WRITING:

- Group work provides instant and increased feedback and a sense of audience - elements often missing from the writing experience.

- The reactions of their peers help student writers understand they are writing for a community of readers.

- The activity reflects real-world writing situations where professionals often collaborate on presentations, reports, and projects.

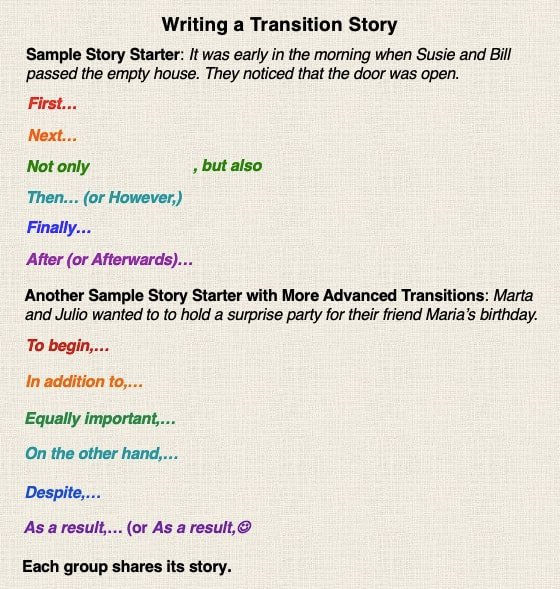

3. USING TRANSITION WORDS & PHRASES

In small groups, students write a Transition Story, all groups beginning with the same sentence and using a list of transition words. They can write multiple sentences between the transitions.

This activity has writers not just learning the effectiveness of transitions but using them for organization in writing).

At different grade levels, include different transitions or transitional phrases (and a more sophisticated starter).

In small groups, students write a Transition Story, all groups beginning with the same sentence and using a list of transition words. They can write multiple sentences between the transitions.

This activity has writers not just learning the effectiveness of transitions but using them for organization in writing).

At different grade levels, include different transitions or transitional phrases (and a more sophisticated starter).

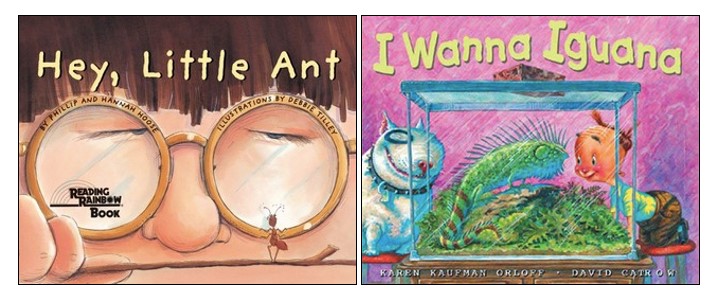

2. INTRODUCING ARGUMENT WRITING

I introduced my ARGUMENT WRITING unit with reading the picture books Hey, Little Ant and I Wanna Iguana.

Students analyzed each of the arguments to identify and evaluate the effectiveness of

1) the claims

2) the counterclaims

3) the evidence (some of which was in the illustrations)

4) the warrants (a general principle that explains why the evidence is relevant to the claim)

or, if missing, students can design warrants to fit the claims and evidence

5) the order of the arguments

6) and to identify ethos, logos, and pathos (especially in Hey, Little Ant).

Teachers can start with #1, 2, and 3 and then add elements to analyze for each argument writing

Students analyzed each of the arguments to identify and evaluate the effectiveness of

1) the claims

2) the counterclaims

3) the evidence (some of which was in the illustrations)

4) the warrants (a general principle that explains why the evidence is relevant to the claim)

or, if missing, students can design warrants to fit the claims and evidence

5) the order of the arguments

6) and to identify ethos, logos, and pathos (especially in Hey, Little Ant).

Teachers can start with #1, 2, and 3 and then add elements to analyze for each argument writing

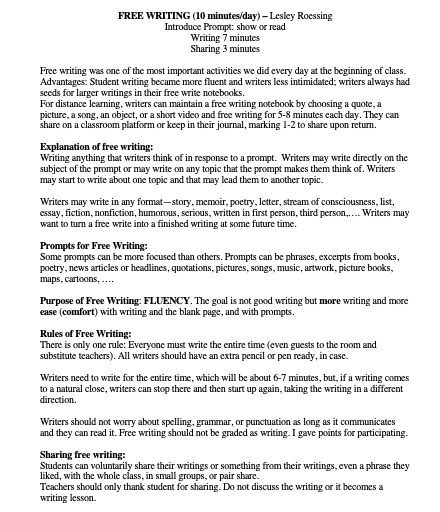

1. FREE WRITING:

One of the most important activities we did every day at the beginning of class for 6-8 minutes (and 2 minute sharing).

ADVANTAGES:

There is only one rule in Free Writing: WRITE.

I always wrote while my writers wrote; I walked around with my journal on a clipboard, writing, encouraging anyone who had stopped with a nod or a pat on the shoulder.

Free Writing was not graded; writers were given points for just writing—freely.

Note: I found as the year progressed, more writers shared their writings or part of their writings (once they realized they no one, even mine, were much better than theirs and that it was not turning into a lesson about what they should or could do)—especially if they tried a different format, such as a poem.

One of the most important activities we did every day at the beginning of class for 6-8 minutes (and 2 minute sharing).

ADVANTAGES:

- Student writing became more fluent.

- Writers were less intimidated by a blank sheet or a test prompt.

- Writers were introduced to new formats as students and teachers share their free writings.

- Writers always had seeds for writings in their free write notebooks.

There is only one rule in Free Writing: WRITE.

I always wrote while my writers wrote; I walked around with my journal on a clipboard, writing, encouraging anyone who had stopped with a nod or a pat on the shoulder.

Free Writing was not graded; writers were given points for just writing—freely.

Note: I found as the year progressed, more writers shared their writings or part of their writings (once they realized they no one, even mine, were much better than theirs and that it was not turning into a lesson about what they should or could do)—especially if they tried a different format, such as a poem.

TEACHER RESPONSE TO FREE WRITING

It is very difficult for us as teachers not to provide feedback, especially supportive feedback, or make something into a lesson.

We have to remember the PURPOSE of an activity. Purpose of free writing is FLUENCY, not good writing but more writing and more ease (comfort) with writing. In response to a writer-shared free writing, teachers should only say “Thank you for sharing.”

If we point out or make comments about what we like:

We have to keep twriters free to write for fluency

However, teachers can refer to good writing in free writes during a writing lesson: “Remember Steph’s writing about the stream? She used verbs such as .…”

It is very difficult for us as teachers not to provide feedback, especially supportive feedback, or make something into a lesson.

We have to remember the PURPOSE of an activity. Purpose of free writing is FLUENCY, not good writing but more writing and more ease (comfort) with writing. In response to a writer-shared free writing, teachers should only say “Thank you for sharing.”

If we point out or make comments about what we like:

- Writers will try to please us – "Steph had good verbs; I will try for good verbs."

- Writers will slow down or stop and revise and worry about word choice/

- Writers will begin reading just to teacher, not to share with fellow writers.

- Writers will notice who you say more to (count words or “weigh” praises). "The teacher said 'Excellent writing' to Sara and only said, 'Good share' to me."

- Writers won't share their writing because they are afraid it’s not good and teachers seem to be looking for "good" if we say what is "good." They don’t realize their writing is not good until teacher points out specifics (Stephanie’s verbs)

We have to keep twriters free to write for fluency

However, teachers can refer to good writing in free writes during a writing lesson: “Remember Steph’s writing about the stream? She used verbs such as .…”

Proudly powered by Weebly