- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

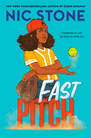

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

- Asian, Asian-American

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

December is Universal Human Rights Month. Suggestion: End the year—or begin the new year— with a study of social justice and human rights.

For years I taught an 8th grade Humanities class centering on the theme of “Human Rights and Issues of Intolerance.” We began with a study of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and read novels about human right issues and violations, including those about the Holocaust, Apartheid, Native rights, rights of citizens with disabilities, free speech, etc., through whole-class, book clubs, and individual self-selected readings, fiction and nonfiction. Novels such as these can be read in Social Studies/History classes with each book club reading a different novel about the same issue (Apartheid) or with each book club reading a novel about a different Human Rights issue.

For years I taught an 8th grade Humanities class centering on the theme of “Human Rights and Issues of Intolerance.” We began with a study of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and read novels about human right issues and violations, including those about the Holocaust, Apartheid, Native rights, rights of citizens with disabilities, free speech, etc., through whole-class, book clubs, and individual self-selected readings, fiction and nonfiction. Novels such as these can be read in Social Studies/History classes with each book club reading a different novel about the same issue (Apartheid) or with each book club reading a novel about a different Human Rights issue.

March 1, 2, and 3; Monster; Yummy: The Last Days of a Southside Shorty; Wings in the Wild*; House Arrest; Loving vs Virginia*; Kent State*; Long Way Down*; Your Heart-My Sky*; Concrete Rose; X, a Novel*; How It Went Down*; The Hate U Give; Allegedly*; Autobiography of My Dead Brother; Illegal*; All American Boys; Hoops; Patron Saints of Nothing*; On the Hook*; Take Me There; Turning 15 on the Road to Freedom; Shooter; The Outsiders; Dear Justyce; Dear Martin*; Durango Street; Moonwalking*; Attack of the Black Rectangles*; We Were the Fire—Birmingham 1963*; Thirst*; Fast Pitch*; Born Behind Bars*; A Good Kind of Trouble; All Rise for the Honorable Perry T. Cook; From the Desk of Zoe Washington*; Front Desk*; Three Keys*; Blended*; Amal Unbound*; Omar Rising*; Ghost Boys*; You Don't Know Everything, Jilly P!*; I Can Make This Promise* *novels reviewed

March 1, 2, and 3; Monster; Yummy: The Last Days of a Southside Shorty; Wings in the Wild*; House Arrest; Loving vs Virginia*; Kent State*; Long Way Down*; Your Heart-My Sky*; Concrete Rose; X, a Novel*; How It Went Down*; The Hate U Give; Allegedly*; Autobiography of My Dead Brother; Illegal*; All American Boys; Hoops; Patron Saints of Nothing*; On the Hook*; Take Me There; Turning 15 on the Road to Freedom; Shooter; The Outsiders; Dear Justyce; Dear Martin*; Durango Street; Moonwalking*; Attack of the Black Rectangles*; We Were the Fire—Birmingham 1963*; Thirst*; Fast Pitch*; Born Behind Bars*; A Good Kind of Trouble; All Rise for the Honorable Perry T. Cook; From the Desk of Zoe Washington*; Front Desk*; Three Keys*; Blended*; Amal Unbound*; Omar Rising*; Ghost Boys*; You Don't Know Everything, Jilly P!*; I Can Make This Promise* *novels reviewed

The 47 novels pictured, 27 of which—my more-recent readings— that are reviewed, reflect our current society and social justice issues and moral dilemmas.

---------------

---------------

Allegedly by Tiffany D. Jackson

This is the story of Mary B. Addison, a 9-year-old who allegedly killed a baby whom her Momma was babysitting. She was sent to baby prison for six years and when readers meet her, she has served her time and is trying to put her life back together. She lives in danger in a group home and, pregnant with a boyfriend, she now wants to clear her name. Can she trust her Momma to help her? And is she guilty?

A novel I couldn’t put down, I read it over one night. Crafted perfectly with narration interrupted with reports, articles, and interviews—from the past and then from the present. The story illustrates our need for connection and for a parent's love

I would recommend for a high school psychology or pre-law class.

---------------

This is the story of Mary B. Addison, a 9-year-old who allegedly killed a baby whom her Momma was babysitting. She was sent to baby prison for six years and when readers meet her, she has served her time and is trying to put her life back together. She lives in danger in a group home and, pregnant with a boyfriend, she now wants to clear her name. Can she trust her Momma to help her? And is she guilty?

A novel I couldn’t put down, I read it over one night. Crafted perfectly with narration interrupted with reports, articles, and interviews—from the past and then from the present. The story illustrates our need for connection and for a parent's love

I would recommend for a high school psychology or pre-law class.

---------------

Amal Unbound by Aisha Saeed

Twelve-year-old Amal lives in a rural Pakistani village where she is the eldest daughter of a small landowner, who like everyone else owes money to the greedy, corrupt landlord. She goes to school and dreams of becoming a teacher. After a run-in with the landlord’s son, she is required to work on the Khan estate to repay her father’s debt, an impossible feat since the servants are charged for lodging and food. As she becomes part of the household, connects with the other servants, and learns more about the unlawful Khan family, she has to decide how much to risk to save the villages, her friends, and her future. She is counseled by her new teacher, “You always have a choice. Making choices even when they scare you because you know it’s the right thing to do —that’s bravery.” (210)

As author Aisha Saeed wrote in her Author’s Note, “Amal is a fictional character, but she represents countless other girls in Pakistan and around the world who take a stand against inequality and fight for justice in often unrecognized but important ways.” In this way novels and characters can function as maps to help our young readers navigate the challenges and ethics of adolescent life.

---------------

Twelve-year-old Amal lives in a rural Pakistani village where she is the eldest daughter of a small landowner, who like everyone else owes money to the greedy, corrupt landlord. She goes to school and dreams of becoming a teacher. After a run-in with the landlord’s son, she is required to work on the Khan estate to repay her father’s debt, an impossible feat since the servants are charged for lodging and food. As she becomes part of the household, connects with the other servants, and learns more about the unlawful Khan family, she has to decide how much to risk to save the villages, her friends, and her future. She is counseled by her new teacher, “You always have a choice. Making choices even when they scare you because you know it’s the right thing to do —that’s bravery.” (210)

As author Aisha Saeed wrote in her Author’s Note, “Amal is a fictional character, but she represents countless other girls in Pakistan and around the world who take a stand against inequality and fight for justice in often unrecognized but important ways.” In this way novels and characters can function as maps to help our young readers navigate the challenges and ethics of adolescent life.

---------------

Attack of the Black Rectangles by Amy Sarig King

“Between the crazy rules around here, my dad being, well, my dad, , and now this [Ms. Sett admonishing Mac to “keep what you learn at home out of my lessons”] I’m done hoping adults do the right thing. I’m done thinking they have our best interests at heart.” (97)

Mac and his family and friends live in the perfect town: No accidents. No crime. No Halloween. No junk food. No “bad” words. No skipping church. And a curfew. It is a town governed by rules made by adults. “These adults join Ms. Sett in letter writing, sitting on the town council and committees, and making rule after rule after rule. They seem to believe that rules equal safety‑by making more rules, they are keeping us all safe and keeping the town’s reputation spotless.” (2)

Mac, a sixth grader; his mother, a hospice worker; and his grandfather, a Vietnam War veteran and meditator, ignore the rules. Mac’s father doesn’t follow the rules, any rules, because he no longer lives with them and he sclaims he is an alien sent to study people and that granddad’s car, when fixed, will be his spaceship. But actually all it will be is stolen by Mac’s dad.

When Mac, his best friend Denis, and his friend/crush Marci are assigned Ms. Sett as their English teacher, they are ambivalent. She seems to be a cool teacher—book club choice reading, writing what you want, and little homework, but she also is the same lady who writes those letters to the paper upholding the town’s rules and not teaching truths, like the truths about Columbus. Also, when Mac, Denis, Marci, Aaron, and Hannah (Hoa) choose Jane Yolen’s The Devil’s Arithmetic, a story about the Holocaust, for book club, they notice black triangles drawn over some of the words.

Puzzled, Mac, Denis, and Marci go to the local bookstore to look at an uncensored copy of the novel. “They crossed out the word ‘breasts’—as if we don’t know what breasts are.” “What grade are you guys in again?” Greg asks. “Sixth,” Marci answers. “Old enough to have actual breasts, so I don’t understand the problem.” (43)

The three friends meet with the principal to report and find out who censored the books. But she doesn’t appear to see a problem. “I should have been born in a time when adults didn’t pretend something is okay when it’s not. I don’t know if that time ever existed.” (77)

Mac writes to author Jane Yolen about the censorship of her book, also sharing some problems about his dad; he keep the communication a secret from his friends. Next the three take the problem to the School Board and with the help of Mac’s grandfather, stage protests on Saturdays in town, speaking with some of the passing citizens. They find more censored books in Ms. Sett’s closet and stage a sit-down protest in the school hallway.

When their proposal is scheduled for the emergency School Board meeting, they find more community support than imagined and some surprising adults advocating on their behalf: Marci’s dad, an attorney; Mac’s mother; Aaron’s dad, who may believe the earth is flat but speaks emotionally about freedom of speech; and one surprise supporter.

After all these meetings, protests, rule changings—and a school dance, Mac has learned two things: No one is ever just one thing. And not everyone is telling the truth. (4)

Amy Sarig King's powerful story for middle-grade readers is about censorship, rules, relationships, truths, and the power of words.

---------------

“Between the crazy rules around here, my dad being, well, my dad, , and now this [Ms. Sett admonishing Mac to “keep what you learn at home out of my lessons”] I’m done hoping adults do the right thing. I’m done thinking they have our best interests at heart.” (97)

Mac and his family and friends live in the perfect town: No accidents. No crime. No Halloween. No junk food. No “bad” words. No skipping church. And a curfew. It is a town governed by rules made by adults. “These adults join Ms. Sett in letter writing, sitting on the town council and committees, and making rule after rule after rule. They seem to believe that rules equal safety‑by making more rules, they are keeping us all safe and keeping the town’s reputation spotless.” (2)

Mac, a sixth grader; his mother, a hospice worker; and his grandfather, a Vietnam War veteran and meditator, ignore the rules. Mac’s father doesn’t follow the rules, any rules, because he no longer lives with them and he sclaims he is an alien sent to study people and that granddad’s car, when fixed, will be his spaceship. But actually all it will be is stolen by Mac’s dad.

When Mac, his best friend Denis, and his friend/crush Marci are assigned Ms. Sett as their English teacher, they are ambivalent. She seems to be a cool teacher—book club choice reading, writing what you want, and little homework, but she also is the same lady who writes those letters to the paper upholding the town’s rules and not teaching truths, like the truths about Columbus. Also, when Mac, Denis, Marci, Aaron, and Hannah (Hoa) choose Jane Yolen’s The Devil’s Arithmetic, a story about the Holocaust, for book club, they notice black triangles drawn over some of the words.

Puzzled, Mac, Denis, and Marci go to the local bookstore to look at an uncensored copy of the novel. “They crossed out the word ‘breasts’—as if we don’t know what breasts are.” “What grade are you guys in again?” Greg asks. “Sixth,” Marci answers. “Old enough to have actual breasts, so I don’t understand the problem.” (43)

The three friends meet with the principal to report and find out who censored the books. But she doesn’t appear to see a problem. “I should have been born in a time when adults didn’t pretend something is okay when it’s not. I don’t know if that time ever existed.” (77)

Mac writes to author Jane Yolen about the censorship of her book, also sharing some problems about his dad; he keep the communication a secret from his friends. Next the three take the problem to the School Board and with the help of Mac’s grandfather, stage protests on Saturdays in town, speaking with some of the passing citizens. They find more censored books in Ms. Sett’s closet and stage a sit-down protest in the school hallway.

When their proposal is scheduled for the emergency School Board meeting, they find more community support than imagined and some surprising adults advocating on their behalf: Marci’s dad, an attorney; Mac’s mother; Aaron’s dad, who may believe the earth is flat but speaks emotionally about freedom of speech; and one surprise supporter.

After all these meetings, protests, rule changings—and a school dance, Mac has learned two things: No one is ever just one thing. And not everyone is telling the truth. (4)

Amy Sarig King's powerful story for middle-grade readers is about censorship, rules, relationships, truths, and the power of words.

---------------

Blended by Sharon M. Draper

“I never stop being amazed that these eighty-eight slices of ivory and ebony can combine to create harmonies.” (51)

Sixth grader Isabella Badia Thornton is a gifted pianist. She also is the daughter of a mother who is white and a father who is Black, a mother and father who are divorced. Izzy spends one week at each house: her mother’s small house where she grew up and where they live with her mother’s boyfriend John Mark and her father’s mansion where they live with his girlfriend Anastasia and Darren, her “totally cool” teenage son. On Sundays Isabella is exchanged between parents at the mall, never a pleasant experience. “Is normal living week to week at different houses? Is normal never being sure of what normal really is?” (161)

Izzy’s dad introduces the idea of racism when he explains why he always dresses well. “The world looks at Black people differently. It’s not fair, but it’s true.…the world can’t see inside of a person, What the world can see is color.” (39)

In school her social studies class studies Civil Rights and the students learn about contemporary racism when a peer’s action is directed at her best friend Imani who is Black. After the incident Isabella asks her father, “Do you think people think I am Black or white when they see me? Am I Black? Or white?” “Yes,” is his reply. “Yes.” (90)

Mr. Kazilly, the language arts/social studies teacher who loves to teach sophisticated vocabulary words helps the students unpack the incident but Izzy learns that sometimes it is those who think they are not racist who also make racist remarks.

The effects of racial profiling become all too real when Darren and Izzy stop for ice cream on the way to her piano recital and on the way back to the car are confronted by the police who are looking for a bank robber. Darren is pushed to the ground and 11-year-old Izzy is shot in the arm.

Sharon Draper’s Blended is a novel about growing up in a racially-diverse and blended family but is also a book about how we are viewed by others, racism, and identity. The short chapters are organized under the titles “Mom’s Week,” “Dad’s Week,” and “Exchange Day.”

---------------

“I never stop being amazed that these eighty-eight slices of ivory and ebony can combine to create harmonies.” (51)

Sixth grader Isabella Badia Thornton is a gifted pianist. She also is the daughter of a mother who is white and a father who is Black, a mother and father who are divorced. Izzy spends one week at each house: her mother’s small house where she grew up and where they live with her mother’s boyfriend John Mark and her father’s mansion where they live with his girlfriend Anastasia and Darren, her “totally cool” teenage son. On Sundays Isabella is exchanged between parents at the mall, never a pleasant experience. “Is normal living week to week at different houses? Is normal never being sure of what normal really is?” (161)

Izzy’s dad introduces the idea of racism when he explains why he always dresses well. “The world looks at Black people differently. It’s not fair, but it’s true.…the world can’t see inside of a person, What the world can see is color.” (39)

In school her social studies class studies Civil Rights and the students learn about contemporary racism when a peer’s action is directed at her best friend Imani who is Black. After the incident Isabella asks her father, “Do you think people think I am Black or white when they see me? Am I Black? Or white?” “Yes,” is his reply. “Yes.” (90)

Mr. Kazilly, the language arts/social studies teacher who loves to teach sophisticated vocabulary words helps the students unpack the incident but Izzy learns that sometimes it is those who think they are not racist who also make racist remarks.

The effects of racial profiling become all too real when Darren and Izzy stop for ice cream on the way to her piano recital and on the way back to the car are confronted by the police who are looking for a bank robber. Darren is pushed to the ground and 11-year-old Izzy is shot in the arm.

Sharon Draper’s Blended is a novel about growing up in a racially-diverse and blended family but is also a book about how we are viewed by others, racism, and identity. The short chapters are organized under the titles “Mom’s Week,” “Dad’s Week,” and “Exchange Day.”

---------------

Born Behind Bars by Padma Venkatraman

Kabir Khan, the son of a Muslim father and Hindu mother, was born behind bars in a prison in Chennai, his mother wrongly accused of a theft before he was born. He has lived his life in deplorable conditions—little food, no privacy, intermittent water availability, and no freedom. His only happiness is being with his Amma and his teacher at the prison school.

But at age 9 his life becomes even more uncertain when, too old to live in prison, he is to be released into the streets. “I tell myself I’m free. I’m outside where I dreamed of going, but I feel like a fish in a net being lifted out of the water I’ve lived in all my life.”(59)

Claimed by a man who says he is his uncle, he faces his first dangerous situation. “My ‘uncle’ is selling me.” (72)

Kabir escapes and navigates the streets with the help of a new friend, the resilient Rana, an adolescent girl who has lived on the streets —and in the trees— and killing her own food—squirrel and crow stews—since her Kurava (Roma) family was attacked, her father killed. She teaches Kabir how to survive street life. He has two goals: to find his father and find a lawyer to release his mother from prison. “I can just imagine Amma walking out of that gray building—me holding one of her hands and my father holding the other.” (93) His command of both Kannada and Tamil languages are an asset and when following his Amma’s wishes to be good, he returns a lady’s lost earring, he and Rana and rewarded with tickets to Bengaluru to find his father’s parents.

In Bengaluru Kabir and Rana learn to trust and find new lives that allow them to both have hope again.

Filled with memorable characters, this emotional story will bring empathy and cultural awareness to upper elementary/middle-grade readers; its short chapters will provide a good read-aloud for teachers, librarians, and parents.

---------------

Kabir Khan, the son of a Muslim father and Hindu mother, was born behind bars in a prison in Chennai, his mother wrongly accused of a theft before he was born. He has lived his life in deplorable conditions—little food, no privacy, intermittent water availability, and no freedom. His only happiness is being with his Amma and his teacher at the prison school.

But at age 9 his life becomes even more uncertain when, too old to live in prison, he is to be released into the streets. “I tell myself I’m free. I’m outside where I dreamed of going, but I feel like a fish in a net being lifted out of the water I’ve lived in all my life.”(59)

Claimed by a man who says he is his uncle, he faces his first dangerous situation. “My ‘uncle’ is selling me.” (72)

Kabir escapes and navigates the streets with the help of a new friend, the resilient Rana, an adolescent girl who has lived on the streets —and in the trees— and killing her own food—squirrel and crow stews—since her Kurava (Roma) family was attacked, her father killed. She teaches Kabir how to survive street life. He has two goals: to find his father and find a lawyer to release his mother from prison. “I can just imagine Amma walking out of that gray building—me holding one of her hands and my father holding the other.” (93) His command of both Kannada and Tamil languages are an asset and when following his Amma’s wishes to be good, he returns a lady’s lost earring, he and Rana and rewarded with tickets to Bengaluru to find his father’s parents.

In Bengaluru Kabir and Rana learn to trust and find new lives that allow them to both have hope again.

Filled with memorable characters, this emotional story will bring empathy and cultural awareness to upper elementary/middle-grade readers; its short chapters will provide a good read-aloud for teachers, librarians, and parents.

---------------

Dear Martin by Nic Stone

Justyce always thought that if he studied hard and stayed out of trouble, he, a black teen from a marginal neighborhood, would do fine and be treated equally. Justyce is a full-scholarship senior at a college preparatory boarding school, captain of the debate team, and has received his acceptance to Yale. Then, helping a drunk ex-girlfriend, who is bi-racial with very light skin, into the back of a car, a white cop slams him around, cuffs him, and takes him to jail. This experience completely challenges his concept of racial equality in America, and Justyce begins writing letters to Martin Luther King, trying to figure out what Martin would do.

When students debate equality in class, Justyce learns that his cousin Manny’s rich white school friends insist that there is equality even as they disrespect him and challenge his college acceptance as affirmative action. Taking his side is his Jewish debate partner, Sara Jane, and Justyce realizes that they have some things in common and falls for her even though he knows his mother will never accept an interracial relationship.

Things escalate, and Justyce loses his sense of where he stands in the world. “Every time I turn on the news and see another black person gunned down, I’m reminded that people look at me and see a threat instead of a human being” (p.95). Manny and Justyce are gunned down by a white, off-duty police officer, and after the trial, Justyce is left even more hopeless “Martin…it never ends, does it?” (p.201), but he does admit, “And maybe that’s my problem. I haven’t really figured out who I am or what I believe yet…, but knowing you [Martin] were my age [when he wrote to the editor of the Atlanta Constitution] gives me hope that maybe I’ve got some time to figure things out”” (p.202).

Jared’s character could have been more developed to make the ending more powerful, but it is certainly another novel that will generate important conversations among readers.

---------------

Justyce always thought that if he studied hard and stayed out of trouble, he, a black teen from a marginal neighborhood, would do fine and be treated equally. Justyce is a full-scholarship senior at a college preparatory boarding school, captain of the debate team, and has received his acceptance to Yale. Then, helping a drunk ex-girlfriend, who is bi-racial with very light skin, into the back of a car, a white cop slams him around, cuffs him, and takes him to jail. This experience completely challenges his concept of racial equality in America, and Justyce begins writing letters to Martin Luther King, trying to figure out what Martin would do.

When students debate equality in class, Justyce learns that his cousin Manny’s rich white school friends insist that there is equality even as they disrespect him and challenge his college acceptance as affirmative action. Taking his side is his Jewish debate partner, Sara Jane, and Justyce realizes that they have some things in common and falls for her even though he knows his mother will never accept an interracial relationship.

Things escalate, and Justyce loses his sense of where he stands in the world. “Every time I turn on the news and see another black person gunned down, I’m reminded that people look at me and see a threat instead of a human being” (p.95). Manny and Justyce are gunned down by a white, off-duty police officer, and after the trial, Justyce is left even more hopeless “Martin…it never ends, does it?” (p.201), but he does admit, “And maybe that’s my problem. I haven’t really figured out who I am or what I believe yet…, but knowing you [Martin] were my age [when he wrote to the editor of the Atlanta Constitution] gives me hope that maybe I’ve got some time to figure things out”” (p.202).

Jared’s character could have been more developed to make the ending more powerful, but it is certainly another novel that will generate important conversations among readers.

---------------

Fast Pitch by Nic Stone

Twelve-year-old Shanice Lockwood is captain of a softball team, the Firebirds, the only all-Black softball team in the Dixie Youth Softball Association. She comes from a long line of batball players—her father, her grandfather PopPop, her great-grandfather. Her one goal is for her team to win the state championship.

But her goal shifts when she meets her Great-Great Uncle Jack, her Great-Grampy JonJon’s brother.

Shanice’s father had to quit baseball when he blew out his knee, his father had to stop playing to support his family, but why did JonJon quit when he was successfully playing for the Negro American League and was one of the first Black players recruited to the MLB? When Shanice is taken to Peachtree Hills Place to meet her sometimes-senile uncle, he tells her that JonJon “didn’t do what they said he did…He was framed.” (46) “My brother ain’t no thief. He didn’t do it…But I know who did.” (47)

And Shanice is off on a quest to research the incident that caused her great grandfather to leave baseball and to see if she, with Jack’s information and JonJon’s leather journal, can clear his name while still trying to lead her softball team to victory.

Fast Pitch is a fun new novel by Nic Stone, full of batball, adventure, a little mystery, peer and family relationships, Negro League history, prejudice, and maybe a first crush.

---------------

Twelve-year-old Shanice Lockwood is captain of a softball team, the Firebirds, the only all-Black softball team in the Dixie Youth Softball Association. She comes from a long line of batball players—her father, her grandfather PopPop, her great-grandfather. Her one goal is for her team to win the state championship.

But her goal shifts when she meets her Great-Great Uncle Jack, her Great-Grampy JonJon’s brother.

Shanice’s father had to quit baseball when he blew out his knee, his father had to stop playing to support his family, but why did JonJon quit when he was successfully playing for the Negro American League and was one of the first Black players recruited to the MLB? When Shanice is taken to Peachtree Hills Place to meet her sometimes-senile uncle, he tells her that JonJon “didn’t do what they said he did…He was framed.” (46) “My brother ain’t no thief. He didn’t do it…But I know who did.” (47)

And Shanice is off on a quest to research the incident that caused her great grandfather to leave baseball and to see if she, with Jack’s information and JonJon’s leather journal, can clear his name while still trying to lead her softball team to victory.

Fast Pitch is a fun new novel by Nic Stone, full of batball, adventure, a little mystery, peer and family relationships, Negro League history, prejudice, and maybe a first crush.

---------------

From the Desk of Zoe Washington by Janae Marks

Statistics affecting our children:

“All the lying was wrong. But maybe it was okay to do something wrong if you were doing it for the right reason.”(180)

Zoe Washington, a rising 7th grader who loves baking and aspires to be the first Black winner of the “Kids Bake Challenge” and publish her own cookbook, is in a fight with her former best friend Trevor, and is not looking forward to a summer without him and her other best friends Jasmine and Maya. But her life changes when, on her 12th birthday, she receives a letter from Marcus, her biological father, a man who she has never met because he has been in prison from before her birth—for murder.

“For the longest time, I didn’t care whether or not I knew my birth father. I had my parents, and they were all I needed. But [Marcus’] letters were making me feel that a part of me was missing, like a chunk of my heart. I was finally filling in that hole.” (121)

Zoe decides to write back, and as she and Marcus exchange letters and music recommendations, she begins to suspect that he doesn’t seem like a murderer. He admits that he did not kill the victim and that there was an alibi witness whom his lawyer never contacted.

Since her mother has forbidden communication with Marcus (and has been confiscating his letters for years), Zoe confides in her grandmother who explains, “People look at someone like Marcus—a tall, strong, dark-skinned boy—and they make assumptions about him. Even if it isn’t right. The jury, the judge, the public, even his own lawyer‑they all assumed Marcus must be guilty because he’s Black. It’s all part of systemic racism.”(133)

Zoe researches the Innocence Project, and she and Trevor, friends again, go on a search for Marcus’ alibi witness in a plan to first prove to herself that Marcus is innocent and if so, to exonerate him.

This is a truly valuable story to begin important conversations about social justice and disparities.

---------------

Statistics affecting our children:

- The rate of wrongful convictions in the United States is estimated to be somewhere between 2 percent and 10 percent. When applied to an estimated prison population of 2.3 million, that means 46,000-230,000 innocent people are locked away. Once an innocent person is convicted, it is next to impossible to get the individual out of prison. Wrongful convictions happen for several reasons; one is bad lawyering by unprepared court-appointed defenders. (Chicago Tribune. March 14, 2018)

- African-American prisoners who are convicted of murder are about 50% more likely to be innocent than other convicted murderers. (National Registry of Exonerations, 2017)

- Currently, an estimated 2.7 million children—or 1 in 28 of those under the age of 18—have a biological mother or father who is incarcerated. According to the National Resource Center on Children and Families of the Incarcerated, approximately 10 million children have experienced parental incarceration at some point in their lives. (http://www.yawednesday.com/blog/resilience-readings-by-lesley-roessing)

“All the lying was wrong. But maybe it was okay to do something wrong if you were doing it for the right reason.”(180)

Zoe Washington, a rising 7th grader who loves baking and aspires to be the first Black winner of the “Kids Bake Challenge” and publish her own cookbook, is in a fight with her former best friend Trevor, and is not looking forward to a summer without him and her other best friends Jasmine and Maya. But her life changes when, on her 12th birthday, she receives a letter from Marcus, her biological father, a man who she has never met because he has been in prison from before her birth—for murder.

“For the longest time, I didn’t care whether or not I knew my birth father. I had my parents, and they were all I needed. But [Marcus’] letters were making me feel that a part of me was missing, like a chunk of my heart. I was finally filling in that hole.” (121)

Zoe decides to write back, and as she and Marcus exchange letters and music recommendations, she begins to suspect that he doesn’t seem like a murderer. He admits that he did not kill the victim and that there was an alibi witness whom his lawyer never contacted.

Since her mother has forbidden communication with Marcus (and has been confiscating his letters for years), Zoe confides in her grandmother who explains, “People look at someone like Marcus—a tall, strong, dark-skinned boy—and they make assumptions about him. Even if it isn’t right. The jury, the judge, the public, even his own lawyer‑they all assumed Marcus must be guilty because he’s Black. It’s all part of systemic racism.”(133)

Zoe researches the Innocence Project, and she and Trevor, friends again, go on a search for Marcus’ alibi witness in a plan to first prove to herself that Marcus is innocent and if so, to exonerate him.

This is a truly valuable story to begin important conversations about social justice and disparities.

---------------

Front Desk by Kelly Yang

Ten-year-old Mia becomes an activist and champion for those who cannot, or will not, stand up for themselves [“You don’t get it, kid. I’ve been fighting my whole life. I’m done. It’s no use fighting—people are gonna be the way they’re gonna be” (105)], teaches others the wrongs of prejudice and injustice, and forms a community from her neighbors, patrons, and fellow immigrants.

Mia and her parents emigrated from China to the United States for a more “free” life. In China her parents were professionals; in America they feel lucky to find a job managing a motel. But the owner, Mr. Yao, is unkind, unjust, cheap, and prejudiced. He reduces their salaries until they are working for lodging and a life of poverty. And while this is a novel about Mia who manages the front desk and helps her parents temporarily hide other Chinese immigrants who have been mistreated, it is really a novel of culture, prejudice, bullying, community, and, most of all, the power of writing. “It was the most incredible feeling ever, knowing that something I wrote actually changed someone’s life.” (218)

In America there are two roller coasters, and people are born to a life on one or the other, but Mia and her friend Lupe, whose family came from Mexico, have decided to break that cycle. Although bullied in school and warned by her mother that she will never be a “native” English writer, Mia develops her writing skills to help Hank gain employment after a wrongful arrest, free “Uncle” Zhang whose ID and passport were being held by his employer, share her story with her teacher and classmates, and finally persuade friends and strangers to take a chance on her family.

Mia is a representative of the “nearly twenty million immigrant children currently living in the United States, 30 percent of whom are living at or below poverty.” (Author’s Note). As such, this book will serve as a mirror for many readers, a map for others looking for ways to navigate young adolescent life, especially in a new culture, and as a window for those who will learn empathy for others they may see as different. Author Kelly Yang also shares the autobiographical elements of the novel in her Author’s Note.

Front Desk, with its very short chapters and challenging topics would be a meaningful and effective 10-minute read-aloud to begin Grade 4-7 daily reading workshop focus lessons. I would suggest projecting Mia’s letters since they show her revisions as she seeks to improve her language skills and word choices.

----------------

Ten-year-old Mia becomes an activist and champion for those who cannot, or will not, stand up for themselves [“You don’t get it, kid. I’ve been fighting my whole life. I’m done. It’s no use fighting—people are gonna be the way they’re gonna be” (105)], teaches others the wrongs of prejudice and injustice, and forms a community from her neighbors, patrons, and fellow immigrants.

Mia and her parents emigrated from China to the United States for a more “free” life. In China her parents were professionals; in America they feel lucky to find a job managing a motel. But the owner, Mr. Yao, is unkind, unjust, cheap, and prejudiced. He reduces their salaries until they are working for lodging and a life of poverty. And while this is a novel about Mia who manages the front desk and helps her parents temporarily hide other Chinese immigrants who have been mistreated, it is really a novel of culture, prejudice, bullying, community, and, most of all, the power of writing. “It was the most incredible feeling ever, knowing that something I wrote actually changed someone’s life.” (218)

In America there are two roller coasters, and people are born to a life on one or the other, but Mia and her friend Lupe, whose family came from Mexico, have decided to break that cycle. Although bullied in school and warned by her mother that she will never be a “native” English writer, Mia develops her writing skills to help Hank gain employment after a wrongful arrest, free “Uncle” Zhang whose ID and passport were being held by his employer, share her story with her teacher and classmates, and finally persuade friends and strangers to take a chance on her family.

Mia is a representative of the “nearly twenty million immigrant children currently living in the United States, 30 percent of whom are living at or below poverty.” (Author’s Note). As such, this book will serve as a mirror for many readers, a map for others looking for ways to navigate young adolescent life, especially in a new culture, and as a window for those who will learn empathy for others they may see as different. Author Kelly Yang also shares the autobiographical elements of the novel in her Author’s Note.

Front Desk, with its very short chapters and challenging topics would be a meaningful and effective 10-minute read-aloud to begin Grade 4-7 daily reading workshop focus lessons. I would suggest projecting Mia’s letters since they show her revisions as she seeks to improve her language skills and word choices.

----------------

Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhoads

Jerome, a black 12-year-old child who is bullied and has made his first friend was playing with a toy gun when a white policeman in a car shot him in the back and then offered no medical help. However, a 911 call misrepresented the 5’, 90-pound Jerome as a person with a gun, rather than a toy gun, and the policeman, against all evidence to the contrary, under oath swore, “I was in fear for my life.” And Jerome questions “when truth is a feeling, can it be both—true and untrue?” (132)

Jerome roams the world as a ghost, and when he and Officer Moore’s daughter Sarah become acquainted, he also meets the ghost of Emmett Till who shares his story. Jerome watches over this family and questions his new role —“Why haven’t I moved on?” (95), his relationship with Sarah, the relationships within Sarah’s family, and his relationships with the Ghost Boys, the hundreds of other black youth who have been killed. As he roams, he sees a Chicago filled with beauty and parks and flowers that was denied him as a child of color and poverty, and a recognition of injustice and tragedy is sparked. As Emmett says, “Someone decided they didn’t like us…. We were a threat, a danger. A menace.” (160) They are children.

I don’t advocate for employing many whole-class novels during the year, but this is a book that will generate important conversations about prejudice, discrimination, stereotyping, fear, and the historical span of racism in this country that need to be held. It also would be a valuable addition to a social studies class study of civil rights and social justice.

---------------

Jerome, a black 12-year-old child who is bullied and has made his first friend was playing with a toy gun when a white policeman in a car shot him in the back and then offered no medical help. However, a 911 call misrepresented the 5’, 90-pound Jerome as a person with a gun, rather than a toy gun, and the policeman, against all evidence to the contrary, under oath swore, “I was in fear for my life.” And Jerome questions “when truth is a feeling, can it be both—true and untrue?” (132)

Jerome roams the world as a ghost, and when he and Officer Moore’s daughter Sarah become acquainted, he also meets the ghost of Emmett Till who shares his story. Jerome watches over this family and questions his new role —“Why haven’t I moved on?” (95), his relationship with Sarah, the relationships within Sarah’s family, and his relationships with the Ghost Boys, the hundreds of other black youth who have been killed. As he roams, he sees a Chicago filled with beauty and parks and flowers that was denied him as a child of color and poverty, and a recognition of injustice and tragedy is sparked. As Emmett says, “Someone decided they didn’t like us…. We were a threat, a danger. A menace.” (160) They are children.

I don’t advocate for employing many whole-class novels during the year, but this is a book that will generate important conversations about prejudice, discrimination, stereotyping, fear, and the historical span of racism in this country that need to be held. It also would be a valuable addition to a social studies class study of civil rights and social justice.

---------------

How It Went Down by Kekla Magoon

I am not usually an advocate of whole class novels, but How It Went Down would be a perfect novel to discuss perspective, interpretation, news bias, and the unreliability of eye witness accounts.

What everyone can agree on was that Tariq Johnson, a black teen, was fatally shot by Jack Franklin, a white man. Was T holding a gun or a Snickers bar? Was he wearing gang colors or did have a red rag in his pocket? Was he being chased for stealing or was the clerk returning his change? It depends on who controls the narrative.

Since there are so many characters (each having a different agenda) sharing their accounts—about the shooting and about the victim—this book would work well with a larger group of readers. Since each account is very short, the book would entice reluctant readers.

This novel wasn't only the narrative of Tariq Johnson and the shooting; it was the collective stories of his community—Tyrell, Jannica, Will, Kimberly—and those who came in contact with T, before and after his death.

----------------

I am not usually an advocate of whole class novels, but How It Went Down would be a perfect novel to discuss perspective, interpretation, news bias, and the unreliability of eye witness accounts.

What everyone can agree on was that Tariq Johnson, a black teen, was fatally shot by Jack Franklin, a white man. Was T holding a gun or a Snickers bar? Was he wearing gang colors or did have a red rag in his pocket? Was he being chased for stealing or was the clerk returning his change? It depends on who controls the narrative.

Since there are so many characters (each having a different agenda) sharing their accounts—about the shooting and about the victim—this book would work well with a larger group of readers. Since each account is very short, the book would entice reluctant readers.

This novel wasn't only the narrative of Tariq Johnson and the shooting; it was the collective stories of his community—Tyrell, Jannica, Will, Kimberly—and those who came in contact with T, before and after his death.

----------------

I Can Make This Promise by Christine Day

“I think about Roger. He was the first person to ever say those words to me. ‘You look Native.’ And it didn’t feel presumptuous. It didn’t feel like a wild guess. It was like he recognized me. Like he saw something in me.” (24)

Twelve-year-old Edie Green knows she is half Native American and that her mother was adopted and raised by a white couple at a very young age. But that is all she knows about her heritage, and she has never thought to ask for whom she is named. She discovered that she was “different” on the first day of kindergarten, a day she remembers in great detail, a day when her teacher’s questions about “where she was from” panicked her. But this was something she and her mother never discussed.

The summer before seventh grade, Edie and her friends discover a box in her attic, a box with pictures and letter from a young woman named Edith who looks just like Edie. When she asks her mother about her name, her mother lies, and a few days later they have a fight when Edie wants to see a movie featuring a Native American character. Now Edie doesn’t know how her mother will react when she tells her she has found the box and has read Edith Graham’s letters. Even her mother’s older brother, Uncle Phil, won’t tell her the secret.

When Edie’s mother finally shares her past and the past of her birth family, “I didn’t picture this. I wasn’t ready for this horrific injustice.” (230)

I Can Make This Promise shares a time of intolerance and injustice in U.S. history, a time before the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 became a vital piece of legislation.

---------------

“I think about Roger. He was the first person to ever say those words to me. ‘You look Native.’ And it didn’t feel presumptuous. It didn’t feel like a wild guess. It was like he recognized me. Like he saw something in me.” (24)

Twelve-year-old Edie Green knows she is half Native American and that her mother was adopted and raised by a white couple at a very young age. But that is all she knows about her heritage, and she has never thought to ask for whom she is named. She discovered that she was “different” on the first day of kindergarten, a day she remembers in great detail, a day when her teacher’s questions about “where she was from” panicked her. But this was something she and her mother never discussed.

The summer before seventh grade, Edie and her friends discover a box in her attic, a box with pictures and letter from a young woman named Edith who looks just like Edie. When she asks her mother about her name, her mother lies, and a few days later they have a fight when Edie wants to see a movie featuring a Native American character. Now Edie doesn’t know how her mother will react when she tells her she has found the box and has read Edith Graham’s letters. Even her mother’s older brother, Uncle Phil, won’t tell her the secret.

When Edie’s mother finally shares her past and the past of her birth family, “I didn’t picture this. I wasn’t ready for this horrific injustice.” (230)

I Can Make This Promise shares a time of intolerance and injustice in U.S. history, a time before the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 became a vital piece of legislation.

---------------

Illegal by Francisco Stork

Francisco’s Stork’s 2017 novel Disappeared takes place in Juarez, Mexico, and depicts sex trafficking, the cartel, murder, poverty, betrayal, abandonment.

Sara Zapata, a young reporter for a local paper, is committed to finding and saving the young women she learns are being kidnapped, including her best friend Linda, despite the warnings of her boss and the threats to herself and her family.

Sara’s younger brother Emiliano, whose life has been affected by his father’s abandonment—of the family and his native Mexico—is looking for a better life, for ways to make money to pay the family bills and win the love of his wealthy girlfriend.

The siblings find in following their consciences, helping others, and making moral choices, they need to do what is right—not what is easy or even safe, and must sacrifice, or revise, their personal goals. To save their lives, Sara and Emiliano escape to the United States to find a better life and to bring the cartel who is trafficking the women to justice. They cross the border and are attacked in the dessert.

Sara turns herself over to the authorities, certain that she meets the requirements for asylum but, as her time in the detention facility grows longer and she observes women being mistreated and deported for no reason, she questions her assumptions. “I imagined that all I had to do was show the authorities the evidence of actual persecution, of actual threats, such as people machine-gunning our house in Juarez.… I saw my case as fitting within the legal reasons for asylum under the law of the United States. Was I wrong about the United States?” (31) She finds, “The whole process of who gets asylum and who gets detained, who gets a bond and who gets released, who gets a visa and who gets deported. I mean, it’s not as rational as I imagined it would be.” (34)

Meanwhile Emiliano enters the country illegally and goes to Chicago with his father, planning to turn Linda’s evidence against the cartel over to the proper authorities. He also finds America to be less than welcoming. As he tells his new friend Aniela, “I think that in Mexico I feel like I belong all the time. I never feel not wanted like I do here sometimes. Here I’m always looking over my shoulder even when no one is there.…knowing that you belong and are wanted is major.” (251)

When Sara’s attorney is killed and she is placed in solitary confinement and Emiliano finds he can no longer trust his father, tensions escalate.

A study of government corruption and the asylum process, Illegal is a thriller that will hook the most reluctant adolescent reader. Enough background is given in Illegal that it may not be y necessary to read Disappeared first, but it would surely enhance the reading.

---------------

Francisco’s Stork’s 2017 novel Disappeared takes place in Juarez, Mexico, and depicts sex trafficking, the cartel, murder, poverty, betrayal, abandonment.

Sara Zapata, a young reporter for a local paper, is committed to finding and saving the young women she learns are being kidnapped, including her best friend Linda, despite the warnings of her boss and the threats to herself and her family.

Sara’s younger brother Emiliano, whose life has been affected by his father’s abandonment—of the family and his native Mexico—is looking for a better life, for ways to make money to pay the family bills and win the love of his wealthy girlfriend.

The siblings find in following their consciences, helping others, and making moral choices, they need to do what is right—not what is easy or even safe, and must sacrifice, or revise, their personal goals. To save their lives, Sara and Emiliano escape to the United States to find a better life and to bring the cartel who is trafficking the women to justice. They cross the border and are attacked in the dessert.

Sara turns herself over to the authorities, certain that she meets the requirements for asylum but, as her time in the detention facility grows longer and she observes women being mistreated and deported for no reason, she questions her assumptions. “I imagined that all I had to do was show the authorities the evidence of actual persecution, of actual threats, such as people machine-gunning our house in Juarez.… I saw my case as fitting within the legal reasons for asylum under the law of the United States. Was I wrong about the United States?” (31) She finds, “The whole process of who gets asylum and who gets detained, who gets a bond and who gets released, who gets a visa and who gets deported. I mean, it’s not as rational as I imagined it would be.” (34)

Meanwhile Emiliano enters the country illegally and goes to Chicago with his father, planning to turn Linda’s evidence against the cartel over to the proper authorities. He also finds America to be less than welcoming. As he tells his new friend Aniela, “I think that in Mexico I feel like I belong all the time. I never feel not wanted like I do here sometimes. Here I’m always looking over my shoulder even when no one is there.…knowing that you belong and are wanted is major.” (251)

When Sara’s attorney is killed and she is placed in solitary confinement and Emiliano finds he can no longer trust his father, tensions escalate.

A study of government corruption and the asylum process, Illegal is a thriller that will hook the most reluctant adolescent reader. Enough background is given in Illegal that it may not be y necessary to read Disappeared first, but it would surely enhance the reading.

---------------

Kent State by Deborah Wiles

“With any story, with any life, with any event whether joyous or tragic, there is so much more to know than the established, inadequate norm: There will be as many versions of the truth as there are persons who lived it.” (Author’s Note, 121)

Deborah Wiles’ historical verse novel Kent State does just that. It tells the story of the Vietnam War protest held on the campus of Kent State University and the students who were wounded and killed when the Ohio National Guard opened fire, students who may or may not have been actively involved in the demonstration. The novel chronicles the four days from Friday, May 1 to Monday, May 4, 1970.

But what is unique is that this is the story told by all the voices those involved, in whatever way—those readers may agree with, and those they may not. Author Salman Rushdie has told audiences that anyone who values freedom of expression should recognize that it must apply also to expression of which they disapprove. In Kent State we hear from protestors, faculty, and students, and friends of the four who were killed—Allison Krause, Jeffrey Miller, Sandy Scheuer, and Bill Schroeder. We also observe the perspectives of the National Guardsmen, the people of the community of Kent, Ohio; and the Black United Students at Kent State. The readers themselves are addressed at times.

---------------

“With any story, with any life, with any event whether joyous or tragic, there is so much more to know than the established, inadequate norm: There will be as many versions of the truth as there are persons who lived it.” (Author’s Note, 121)

Deborah Wiles’ historical verse novel Kent State does just that. It tells the story of the Vietnam War protest held on the campus of Kent State University and the students who were wounded and killed when the Ohio National Guard opened fire, students who may or may not have been actively involved in the demonstration. The novel chronicles the four days from Friday, May 1 to Monday, May 4, 1970.

But what is unique is that this is the story told by all the voices those involved, in whatever way—those readers may agree with, and those they may not. Author Salman Rushdie has told audiences that anyone who values freedom of expression should recognize that it must apply also to expression of which they disapprove. In Kent State we hear from protestors, faculty, and students, and friends of the four who were killed—Allison Krause, Jeffrey Miller, Sandy Scheuer, and Bill Schroeder. We also observe the perspectives of the National Guardsmen, the people of the community of Kent, Ohio; and the Black United Students at Kent State. The readers themselves are addressed at times.

---------------

Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds

Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote "Poetry: The best words in the best order."

This novel by Jason Reynolds, his first verse novel, proves that maybe more than any verse novel I have read. I have read quite a lot of verse novels (my favorite genre) and have read many great, lyrical verse with very effective line breaks. But in this novel, every single word, punctuation, and spacing counts. It is a perfect novel for reluctant readers because, even though the words are simple to read, the story generates inference, prediction, making connections re-reading, and employs all the reading strategies necessary to a good reader. It also brings up ideas of loss and retaliation and where, or if, we can break the chain of violence and who makes that decision for us.

This novel takes the reader a long way down—in the space of a minute.

---------------

Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote "Poetry: The best words in the best order."

This novel by Jason Reynolds, his first verse novel, proves that maybe more than any verse novel I have read. I have read quite a lot of verse novels (my favorite genre) and have read many great, lyrical verse with very effective line breaks. But in this novel, every single word, punctuation, and spacing counts. It is a perfect novel for reluctant readers because, even though the words are simple to read, the story generates inference, prediction, making connections re-reading, and employs all the reading strategies necessary to a good reader. It also brings up ideas of loss and retaliation and where, or if, we can break the chain of violence and who makes that decision for us.

This novel takes the reader a long way down—in the space of a minute.

---------------

Loving vs. Virginia: A Documentary Novel of the Landmark Civil Rights Case by Patricia Hruby Powell

Loving vs Virgina is the story behind the unanimous landmark decision of June 1967. Told in free verse through alternating narrations by Richard and Mildred, the events begin in Fall 1952 when 13-year old Mildred notices that her desk in the colored school is “ sad excuse for a desk” and her reader “reeks of grime and mildew and has been in the hands of many boys,” but she also relates the closeness of family and friends in her summer vacation essay. This closeness is also expressed in the family’s Saturday dinner where “folks drop by,” one of them being the boy who catches Mildred’s ball during the kickball game and “Because of him I don’t get home.” That boy is her neighbor, nineteen-year-old Richard Loving, and that phrase becomes truer than Mildred could have guessed.

On June 2, 1958, Richard, who is white, and Mildred marry in Washington, D.C., and on July 11, 1958 they are arrested at her parents’ house in Virginia. The couple spends the next ten years living in D.C., sneaking into Virginia, and finally contacting the American Civil Liberties Union who brings their case through the courts to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The documentary novel brings the story behind the case alive, interspersed with quotes, news headlines and news reports, maps, timelines, and information on the various court cases, and the players involved, as the case made its way to the Supreme Court.

---------------

Loving vs Virgina is the story behind the unanimous landmark decision of June 1967. Told in free verse through alternating narrations by Richard and Mildred, the events begin in Fall 1952 when 13-year old Mildred notices that her desk in the colored school is “ sad excuse for a desk” and her reader “reeks of grime and mildew and has been in the hands of many boys,” but she also relates the closeness of family and friends in her summer vacation essay. This closeness is also expressed in the family’s Saturday dinner where “folks drop by,” one of them being the boy who catches Mildred’s ball during the kickball game and “Because of him I don’t get home.” That boy is her neighbor, nineteen-year-old Richard Loving, and that phrase becomes truer than Mildred could have guessed.

On June 2, 1958, Richard, who is white, and Mildred marry in Washington, D.C., and on July 11, 1958 they are arrested at her parents’ house in Virginia. The couple spends the next ten years living in D.C., sneaking into Virginia, and finally contacting the American Civil Liberties Union who brings their case through the courts to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The documentary novel brings the story behind the case alive, interspersed with quotes, news headlines and news reports, maps, timelines, and information on the various court cases, and the players involved, as the case made its way to the Supreme Court.

---------------

Moonwalking by Zetta Elliott and Lyn Miller-Lachmann

Solidarity means

we all belong together

we all work together

we’re like union brothers

and sisters

but my family is broken

and scattered

in Poland and in America

and I’m here alone.

Loner or Leader

Time to choose. (109)

Two adolescents in early 1980’s. Some similarities; major differences.

When JJ Pankoski’s father goes on strike and is fired and blacklisted, they lose their home and car and move into the Polish grandparent’s house in Brooklyn where possibly JJ won’t be bullied as he was in his former school. A musician, JJ saves is his Casio keyboard, Walkman headphones, and punk-rock cassettes. But one other thing he loses is his sister Alina who remains in Lynbrook with a secret.

Pie, or Pierre Velez, lives with his Puerto Rican mother who suffers from mental illness, and his younger half-sister Pilar, yearns to have known his African father. He also is an artist, tagging buildings and recommended for a prestigious art class at the museum.

“what means

the most to me?

family always comes first

then

my culture

my friends

my girl

my ‘hood

my future

my dreams” (96)

JJ desperately needs a friend,

“maybe [Pi] can help me

because he likes to get answers right

and explain to kids

who

don’t

understand.

and maybe he’ll even

like me.” (84)

and, for a short while, Pie is that friend, the two boys connected by their love of the arts.

But Pie lives with discrimination.

“…this is the one night

when anything goes—you can be anyone on Halloween

pretend you got special powers knowing full well that

the next day you’ll go back to being an ordinary kid

who hungers for heroes that Hollywood won’t create” (104)

and when the class social studies project is assigned,

“Now we got this project—we have to write

about a leader who changed the world and I don’t wanna write about

some dead white guy…even though I know that’s the only way

to get an A.” (113)

But one night when they are tagging, Pie is arrested and JJ, as a white adolescent, is not only let go but driven home by the policeman (“Different Justice”). JJ is guilty for doing nothing.

Later, when he receives a much higher grade than Pie for a report on which Pie coached him, still was inferior to his friend’s

“because Pie’s report

on Patrice Lumumba

was way better

than mine.

Pie told me to dig deeper

But he

dug

deepest

of all.” (162-3)

JJ speaks out, but it is too little too late.

“true friends

don’t leave you

hanging

true friends

always have

your back.” (159)

Written in creatively-formatted free verse and co-authored by Zetta Elliott, who writes the voice of Pie, and Lyn Miller-Lachmann, who writes JJ’s narrative, Moonwalking is a work of history, laws, prejudice and discrimination, poverty, mental illness, neuro-diversity, art, and friendship.

---------------

Solidarity means

we all belong together

we all work together

we’re like union brothers

and sisters

but my family is broken

and scattered

in Poland and in America

and I’m here alone.

Loner or Leader

Time to choose. (109)

Two adolescents in early 1980’s. Some similarities; major differences.

When JJ Pankoski’s father goes on strike and is fired and blacklisted, they lose their home and car and move into the Polish grandparent’s house in Brooklyn where possibly JJ won’t be bullied as he was in his former school. A musician, JJ saves is his Casio keyboard, Walkman headphones, and punk-rock cassettes. But one other thing he loses is his sister Alina who remains in Lynbrook with a secret.

Pie, or Pierre Velez, lives with his Puerto Rican mother who suffers from mental illness, and his younger half-sister Pilar, yearns to have known his African father. He also is an artist, tagging buildings and recommended for a prestigious art class at the museum.

“what means

the most to me?

family always comes first

then

my culture

my friends

my girl

my ‘hood

my future

my dreams” (96)

JJ desperately needs a friend,

“maybe [Pi] can help me

because he likes to get answers right

and explain to kids

who

don’t

understand.

and maybe he’ll even

like me.” (84)

and, for a short while, Pie is that friend, the two boys connected by their love of the arts.

But Pie lives with discrimination.

“…this is the one night

when anything goes—you can be anyone on Halloween

pretend you got special powers knowing full well that

the next day you’ll go back to being an ordinary kid

who hungers for heroes that Hollywood won’t create” (104)

and when the class social studies project is assigned,

“Now we got this project—we have to write

about a leader who changed the world and I don’t wanna write about

some dead white guy…even though I know that’s the only way

to get an A.” (113)

But one night when they are tagging, Pie is arrested and JJ, as a white adolescent, is not only let go but driven home by the policeman (“Different Justice”). JJ is guilty for doing nothing.

Later, when he receives a much higher grade than Pie for a report on which Pie coached him, still was inferior to his friend’s

“because Pie’s report

on Patrice Lumumba

was way better

than mine.

Pie told me to dig deeper

But he

dug

deepest

of all.” (162-3)

JJ speaks out, but it is too little too late.

“true friends

don’t leave you

hanging

true friends

always have

your back.” (159)

Written in creatively-formatted free verse and co-authored by Zetta Elliott, who writes the voice of Pie, and Lyn Miller-Lachmann, who writes JJ’s narrative, Moonwalking is a work of history, laws, prejudice and discrimination, poverty, mental illness, neuro-diversity, art, and friendship.

---------------

On the Hook by Francisco Stork

“Respect and disrespect. Killing and revenge and cowardice. Stupid, meaningless words, all of them. None of them worth dying for.” (270)

Hector and his family were still grieving the loss of his father to cancer, his brother dealing with it through drinking. But Hector was a good, smart kid on his way to a better life. Then things were finally looking up; Fili was drinking less, in love, and planning to buy a house to move the family out of the projects where Chavo, the drug dealer, and his brother Joey ran things. What would induce Hector, a chess team champion, writing contest winner with college aspirations, who worked a grocery job to help his mother pay the bills, to confess to a crime in order to end up in reform school.

At school and home in the projects, Joey threatens to kill Hector, carving a “C” in Hector’s chest, and Hector becomes consumed with the shame of his own cowardice. When Joey kills Fili, he and Hector are sent to the same reform school, where Hector has to decide how to make things “balance[d]” as decreed by the apparition of his father. Should he humiliate Joey in the boxing ring and then kill him? Will those acts make him less of a coward? Or does he listen to his many mentors?

“X-Man went suddenly quiet. He looked as if he was remembering something painful. ‘Dude, you gotta find a way to move on. When your flashlight’s stuck like that, you’re not seeing, like Mr. Diaz says. And seeing’s the only way to free yourself.’” (214)

Francisco Stork’s newest novel is filled with 3-dimensional characters who jump off the page into the reader’s heart. I felt protective of Hector, wanting to cheer him on and shake him and counsel him. I grieved for Fili and his lost future as if I had known him. Even Joey, the villain, came alive as his story validates the idea that everyone has a back story and their own demons.

Maybe the balance Hector needs to create is in himself.

---------------

“Respect and disrespect. Killing and revenge and cowardice. Stupid, meaningless words, all of them. None of them worth dying for.” (270)

Hector and his family were still grieving the loss of his father to cancer, his brother dealing with it through drinking. But Hector was a good, smart kid on his way to a better life. Then things were finally looking up; Fili was drinking less, in love, and planning to buy a house to move the family out of the projects where Chavo, the drug dealer, and his brother Joey ran things. What would induce Hector, a chess team champion, writing contest winner with college aspirations, who worked a grocery job to help his mother pay the bills, to confess to a crime in order to end up in reform school.

At school and home in the projects, Joey threatens to kill Hector, carving a “C” in Hector’s chest, and Hector becomes consumed with the shame of his own cowardice. When Joey kills Fili, he and Hector are sent to the same reform school, where Hector has to decide how to make things “balance[d]” as decreed by the apparition of his father. Should he humiliate Joey in the boxing ring and then kill him? Will those acts make him less of a coward? Or does he listen to his many mentors?

“X-Man went suddenly quiet. He looked as if he was remembering something painful. ‘Dude, you gotta find a way to move on. When your flashlight’s stuck like that, you’re not seeing, like Mr. Diaz says. And seeing’s the only way to free yourself.’” (214)

Francisco Stork’s newest novel is filled with 3-dimensional characters who jump off the page into the reader’s heart. I felt protective of Hector, wanting to cheer him on and shake him and counsel him. I grieved for Fili and his lost future as if I had known him. Even Joey, the villain, came alive as his story validates the idea that everyone has a back story and their own demons.

Maybe the balance Hector needs to create is in himself.

---------------

Omar Rising by Aisha Saaed

“What about the boys on the other side of the wall? Picking whatever activities they’d like because they were born into families who can pay their tuition. [The headmaster] is right. I’m lucky. But it’s hard to feel that way right now.”

Omar lives in a one-room hut with his mother, a servant for the family of Omar’s best friend Amal. When Omar is accepted to the prestigious Ghalib Academy for Boys as a scholarship student, his whole town celebrates. He is aware that his future opportunities have widened, but he is particularly excited about the extracurricular activities, especially the astronomy club since he has always wanted to be an astronomer.

At school Omar immediately makes friends—Marwan and Jabril from Orientation; Kareem, his roommate and one of the scholarship kids along with Naveed, and soon others, especially when they observe Omar’s soccer skills. The only unfriendly person appears to be their neighbor Aiden. And Headmaster Moiz, the English teacher for the scholarship students or, as he says, “kids like you,” who appears to take an instant dislike to Omar. Despite having the academics to be accepted, the scholarship kids find the studies difficult, no matter how hard they study.

And then they find out that Scholar Boys are not permitted to join any activities or sports; instead they have to do hours of chores.

“Back home, everyone was proud of me.

Back home, everyone was jostling for me to be part of their team.

But I’m not home now.” (ARC, 56)

“I’m the kid doing chores. Who can’t do any of the fun after-school activities. Struggling to keep up with my classes.” (ARC, 153)

Omar and Naveed and the others fulfill their work hours, mainly in the kitchen with the chef Shauib and his son Basem where Omar finds he has some talent and where they can keep their secret from the other students (who think they are just nerds, studying all the time). “Marwan acts like we think being stuck in a room on a Friday night instead of out having fun is what we want to do. He doesn’t get it. Because he can’t.” (ARC, 109)

But the boys find out that the system is rigged. Most of the Scholar Boys are not expected to stay beyond the first year. Studying together with the other scholarship boys, night and day, Omar does well in science and math but continues to do poorly in English until he asks the Headmaster to tutor him.. “Finding out how hard it was to actually stay at this school, I’d started pushing away my dreams, afraid it would hurt more if it all crashed down. But maybe holding onto your dreams is how you make your way through.” (ARC, 117) He raises his grades but it is not enough; SBs are to maintain an A+.

For his art class final project, Omar studies Shehzil Maik, a local artist who works in many mediums to promote justice, equality, and resistance. With her influence, he designs his own collage, “Stubbornly Optimistic.” During his presentation Omar shares the injustice he and the other Scholar Boys are facing. “We might go to the same school, but the rules are completely different for us.… We might be in the same classes but we are from different classes.” (ARC, 176)

However, when the school unites to fight the discrimination, he finds that art can be a catalyst for change. This is a story of a young boy who is not only strong and resilient but one who is willing to make a difference for himself and future boys.

Note: This novel is a companion novel to Aisha Saeed’s Amal Unbound; even though a sequel in time, it can be read independently.

---------------

“What about the boys on the other side of the wall? Picking whatever activities they’d like because they were born into families who can pay their tuition. [The headmaster] is right. I’m lucky. But it’s hard to feel that way right now.”

Omar lives in a one-room hut with his mother, a servant for the family of Omar’s best friend Amal. When Omar is accepted to the prestigious Ghalib Academy for Boys as a scholarship student, his whole town celebrates. He is aware that his future opportunities have widened, but he is particularly excited about the extracurricular activities, especially the astronomy club since he has always wanted to be an astronomer.

At school Omar immediately makes friends—Marwan and Jabril from Orientation; Kareem, his roommate and one of the scholarship kids along with Naveed, and soon others, especially when they observe Omar’s soccer skills. The only unfriendly person appears to be their neighbor Aiden. And Headmaster Moiz, the English teacher for the scholarship students or, as he says, “kids like you,” who appears to take an instant dislike to Omar. Despite having the academics to be accepted, the scholarship kids find the studies difficult, no matter how hard they study.

And then they find out that Scholar Boys are not permitted to join any activities or sports; instead they have to do hours of chores.

“Back home, everyone was proud of me.

Back home, everyone was jostling for me to be part of their team.

But I’m not home now.” (ARC, 56)

“I’m the kid doing chores. Who can’t do any of the fun after-school activities. Struggling to keep up with my classes.” (ARC, 153)

Omar and Naveed and the others fulfill their work hours, mainly in the kitchen with the chef Shauib and his son Basem where Omar finds he has some talent and where they can keep their secret from the other students (who think they are just nerds, studying all the time). “Marwan acts like we think being stuck in a room on a Friday night instead of out having fun is what we want to do. He doesn’t get it. Because he can’t.” (ARC, 109)

But the boys find out that the system is rigged. Most of the Scholar Boys are not expected to stay beyond the first year. Studying together with the other scholarship boys, night and day, Omar does well in science and math but continues to do poorly in English until he asks the Headmaster to tutor him.. “Finding out how hard it was to actually stay at this school, I’d started pushing away my dreams, afraid it would hurt more if it all crashed down. But maybe holding onto your dreams is how you make your way through.” (ARC, 117) He raises his grades but it is not enough; SBs are to maintain an A+.

For his art class final project, Omar studies Shehzil Maik, a local artist who works in many mediums to promote justice, equality, and resistance. With her influence, he designs his own collage, “Stubbornly Optimistic.” During his presentation Omar shares the injustice he and the other Scholar Boys are facing. “We might go to the same school, but the rules are completely different for us.… We might be in the same classes but we are from different classes.” (ARC, 176)