- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

- Asian, Asian-American

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

Almost one out of four (23 percent) public school students in the United States came from an immigrant household in 2015. (Center for Immigration Studies) Immigrant-origin students accounted in 2018 for 5.3 million students, or 28% of all students, in higher education. FWD.us estimates that approximately 620,000 K-12 students in the United States are undocumented. In 2021, immigrants comprised 13.6 percent of the total U.S. population. Approximately 18 million U.S. children under age 18 lived with at least one immigrant parent in 2021. They accounted for 26 percent of the 69.7 million children under age 18 in the United States. Most of these children are native born; 12 percent (2.2 million) were born outside the United States. (Migration Policy Institute).

The key difference between immigrants and refugees is that an immigrant chooses to leave their country of origin. A refugee, on the other hand, is compelled to seek asylum in another country, fleeing persecution or conflict in her or his country of origin. More relevant immigration/refugee statistics are included in some of the book reviews below.

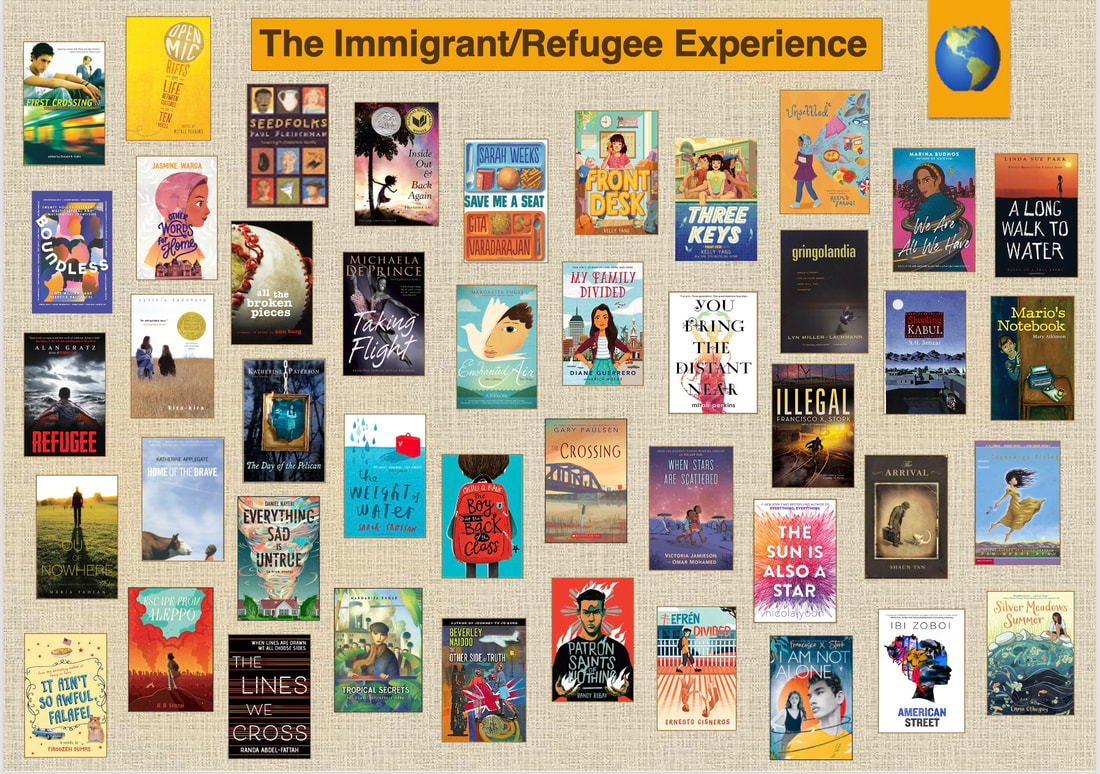

Pictured are 43 novels, memoirs, and anthologies that I have read and recommend to Upper Elementary, Middle Grade, and High School teachers and librarians to share the immigrant/refugee experience. Below I review 22 of my more recently-read texts.

The key difference between immigrants and refugees is that an immigrant chooses to leave their country of origin. A refugee, on the other hand, is compelled to seek asylum in another country, fleeing persecution or conflict in her or his country of origin. More relevant immigration/refugee statistics are included in some of the book reviews below.

Pictured are 43 novels, memoirs, and anthologies that I have read and recommend to Upper Elementary, Middle Grade, and High School teachers and librarians to share the immigrant/refugee experience. Below I review 22 of my more recently-read texts.

SHORT STORY ANTHOLOGIES: Boundless, First Crossing, Open Mic VERSE NOVELS: All the Broken Pieces, Home of the Brave Pieces, Inside Out & Back Again, Other Words for Home, The Weight of Water, Tropical Secrets: Holocaust Refugees in Cuba, Unsettled

MEMOIRS: Enchanted Air, Everything Sad is Untrue, My Family Divided, Taking Flight

Graphic: The Arrival, When Stars Are Scattered

PROSE NOVELS: A Long Walk to Water, American Street, Efren Divided, Esperanza Rising,

Front Desk and Three Keys, Gringolandia, I Am Not Alone, Illegal

It Ain’t So Awful, Falafel, Kira-Kira, Mario’s Notebook, Out of Nowhere, Patron Saints of Nothing, Refugee, Save Me a Seat, Seedfolks, Shooting Kabul, Silver Meadows Summer, The Boy at the Back of the Class, The Crossing, The Day of the Pelican, The Lines We Cross, The Other Side of Truth, The Sun is Also a Star, We Are All We Have, You Bring the Distant Near

BOUNDLESS: Twenty Voices Celebrating Multicultural and Multiracial Identities edited by Ismee Amiel Williams & Rebecca Barcarcel

The U.S. population is undergoing rapid racial and ethnic change. The multiracial population in the United States—those who identify with two or more races—is also increasing with the rise in interracial couples. The children of these interracial unions are forming a new generation that is much more likely to identify with multiple racial groups. By 2060, about 6 percent of the total population—and 11 percent of children under age 18—are projected to be multiracial. (Population Reference Bureau)

Most of us have felt, from time to time, that we don’t fit in—with our peers, our communities, our families, even our own skins—for a variety of reasons. These are twenty stories of adolescents who don’t feel they fit in or they are not “whole” because they are multiracial or multicultural. Boundless shares the multiracial and multicultural experience of contemporary adolescents.

Nina feels that she is not Asian enough to be a part of her extended family. “Sometimes I wonder of karaoke nights [with the family] would’ve felt different if I’d grown up where Dad did, around more people who looked like me. So many people in Hawaii are multiracial. It isn’t weird or different or ‘exotic’, like I’ve been called all my life.” (24)

Amalia Lipski is Hispanic-Jewish. “By trying to hold on to those two identities, I feel like I’m doing a disservice to both. Like, I’m trying to find the right balance, but I want to be more than fifty percent Judia and fifty percent Latina. I want to be two hundred percent everything. I want to be more than what everybody expects me to be. I want to be…perfect.” (42)

Tami is Japanese-Jewish. “I swore I wouldn’t…divide myself up. Not after I teacher called me half-and-half in elementary school…. Am I too much of something? Not enough of another? I know what I am not—whole.” (75)

Irene is Mexican-Irish, “EE-reh-neh to my mom’s side of the family (the Mexican side); Eye-reen to my dad’s side of the family (the Irish side)…. My goal in life is to keep my head down.” (85) “There is no way to divide myself and put the pieces into nice little boxes.” (96)

Eitan is Israeli-Mexican and feels invisible. “Was a person more defined by where they were born or where their parents were born? If some government or the other decided to take away either one of his nationalities, he would still be Eitan.” (124)

Madison Rabottini is Italian-Chinese. “There is nothing quite like doing a Zoom party with the Italian side of the family to realize how out of place my brother and I look in box after box of curly hair and hazel eyes. Then we flip to a Skype of my mom’s side, and suddenly Dad is the outsider.” (140)

Lydia is biracial, Indian-White. “There have been opposing forces within me for as long as I can remember. I am twins inhabiting the same body, two chemicals combined to form a unique reaction.” (277) “I am not Indian enough. Sometimes I don’t even feel American enough. I am not enough.” (280)

Simone is biracial; Sean is of Honduran decent, adopted by an Irish couple; Trevor is Black-Puerto Rican; Jerry is Filipino White; and, after his death, Hiba Ahmed visits her father’s homeland, Jordan. “I just want to know more about where he was from. About where I’m from.” “349

Here are stories for those who have not felt “enough” for any reason. As I wrote in my review for Black Enough, this is a book that invites some adolescents to see their lives and experiences reflected and invites others to experience the lives of their contemporaries.

The U.S. population is undergoing rapid racial and ethnic change. The multiracial population in the United States—those who identify with two or more races—is also increasing with the rise in interracial couples. The children of these interracial unions are forming a new generation that is much more likely to identify with multiple racial groups. By 2060, about 6 percent of the total population—and 11 percent of children under age 18—are projected to be multiracial. (Population Reference Bureau)

Most of us have felt, from time to time, that we don’t fit in—with our peers, our communities, our families, even our own skins—for a variety of reasons. These are twenty stories of adolescents who don’t feel they fit in or they are not “whole” because they are multiracial or multicultural. Boundless shares the multiracial and multicultural experience of contemporary adolescents.

Nina feels that she is not Asian enough to be a part of her extended family. “Sometimes I wonder of karaoke nights [with the family] would’ve felt different if I’d grown up where Dad did, around more people who looked like me. So many people in Hawaii are multiracial. It isn’t weird or different or ‘exotic’, like I’ve been called all my life.” (24)

Amalia Lipski is Hispanic-Jewish. “By trying to hold on to those two identities, I feel like I’m doing a disservice to both. Like, I’m trying to find the right balance, but I want to be more than fifty percent Judia and fifty percent Latina. I want to be two hundred percent everything. I want to be more than what everybody expects me to be. I want to be…perfect.” (42)

Tami is Japanese-Jewish. “I swore I wouldn’t…divide myself up. Not after I teacher called me half-and-half in elementary school…. Am I too much of something? Not enough of another? I know what I am not—whole.” (75)

Irene is Mexican-Irish, “EE-reh-neh to my mom’s side of the family (the Mexican side); Eye-reen to my dad’s side of the family (the Irish side)…. My goal in life is to keep my head down.” (85) “There is no way to divide myself and put the pieces into nice little boxes.” (96)

Eitan is Israeli-Mexican and feels invisible. “Was a person more defined by where they were born or where their parents were born? If some government or the other decided to take away either one of his nationalities, he would still be Eitan.” (124)

Madison Rabottini is Italian-Chinese. “There is nothing quite like doing a Zoom party with the Italian side of the family to realize how out of place my brother and I look in box after box of curly hair and hazel eyes. Then we flip to a Skype of my mom’s side, and suddenly Dad is the outsider.” (140)

Lydia is biracial, Indian-White. “There have been opposing forces within me for as long as I can remember. I am twins inhabiting the same body, two chemicals combined to form a unique reaction.” (277) “I am not Indian enough. Sometimes I don’t even feel American enough. I am not enough.” (280)

Simone is biracial; Sean is of Honduran decent, adopted by an Irish couple; Trevor is Black-Puerto Rican; Jerry is Filipino White; and, after his death, Hiba Ahmed visits her father’s homeland, Jordan. “I just want to know more about where he was from. About where I’m from.” “349

Here are stories for those who have not felt “enough” for any reason. As I wrote in my review for Black Enough, this is a book that invites some adolescents to see their lives and experiences reflected and invites others to experience the lives of their contemporaries.

OPEN MIC: Riffs on Life between Cultures in Ten Voices edited by Mitali Perkins

Growing up different in the neighborhood, in the school, in the dominant local culture—that is something I can relate to. Singing Christmas songs in assemblies, humming during the J word; decorating my house with dreidels as my neighbors turned on their lighted trees; hiding my matzoh sandwiches in the school cafeteria; sitting on my porch on Sundays while all the neighbor kids went to church. This is what the authors share in Open Mic—the ten stories, or “riffs on life,” of being culturally different.

Open Mic should be in every MS/HS classroom library, preferably a copy for every student to read, a collection of stories that will generate important conversations about race and culture and fitting in.

Written in a variety of styles—graphic stories, free verse, and prose—and perspectives—first person and third, memoir and fiction (or maybe fictionalized versions of memoir) by ten different authors, many who will be recognized by adolescent readers, there are stories that will appeal to all readers and are necessary for many adolescents.

They are all short, which will appeal to our "reluctant"readers and about a wide variety of cultures, which may welcome our ELL students. Many are hilarious; editor and author Mitali Perkins explains that humor is “the best way to ease…conversations about race” (Introduction), and all are enlightening. Truly, this is a collection of stories that will serve as mirrors, maps, and windows.

Growing up different in the neighborhood, in the school, in the dominant local culture—that is something I can relate to. Singing Christmas songs in assemblies, humming during the J word; decorating my house with dreidels as my neighbors turned on their lighted trees; hiding my matzoh sandwiches in the school cafeteria; sitting on my porch on Sundays while all the neighbor kids went to church. This is what the authors share in Open Mic—the ten stories, or “riffs on life,” of being culturally different.

Open Mic should be in every MS/HS classroom library, preferably a copy for every student to read, a collection of stories that will generate important conversations about race and culture and fitting in.

Written in a variety of styles—graphic stories, free verse, and prose—and perspectives—first person and third, memoir and fiction (or maybe fictionalized versions of memoir) by ten different authors, many who will be recognized by adolescent readers, there are stories that will appeal to all readers and are necessary for many adolescents.

They are all short, which will appeal to our "reluctant"readers and about a wide variety of cultures, which may welcome our ELL students. Many are hilarious; editor and author Mitali Perkins explains that humor is “the best way to ease…conversations about race” (Introduction), and all are enlightening. Truly, this is a collection of stories that will serve as mirrors, maps, and windows.

OTHER WORDS FOR HOME by Jasmine Warga (verse novel)

What happens when you have to leave your home to leave far away within another culture? How does that place become “home”?

When trouble spreads to Jude’s small city on the sea, a city formerly filled with tourists, and her older brother joins the revolution, seventh-grader Jude and her pregnant mother immigrate to America, leaving behind her Baba, his store, and her best friend to move in with her uncle, his American wife and their daughter. Life in Cincinnati is very different; Jude’s English is not as good as she had hoped and her popular seventh-grade cousin Sarah is afraid she will seem “weird,” like her new friend Layla whose parents came from Lebanon and wears a hajab.

Jude tries to assimilate but

“I am no longer/a girl./I am a Middle Eastern girl./A Syrian girl./A Muslim girl.

Americans love labels./They help them know what to expect./Sometimes, though,/I think labels stop them from/thinking.” (92)

As she learns more English, practicing slang with the four members of her ESL class, and becomes friends with Layla and Miles, a boy from her math class fascinated with stars and the galaxy, Jude misses Baba, Fatima, and Auntie Amal, and worries about Issa; however, she becomes closer to her aunt, speaks Arabic with her uncle, and starts thinking of the old house as home. Becoming a young woman, she begins wearing her scarves, although she has to convince her aunt that this is her choice.

Jude discovers that belonging is complicated. Layla tells her she is “lucky” that she comes from somewhere rather than being a Middle Eastern girl in America who, if she moved to Jordan, would be an American girl in the Middle East. “Lucky. I am learning how to say it/over and over again in English./I am learning how it tastes—/sweet with promise/and bitter with responsibility.” (168) Even the very American teen Sarah seems to want to embrace her other culture; she asks to learn Arabic and points out that, as cousins, they look much alike.

When Jude follows her brother’s wish that she be brave, she tries out for the school musical, even though Layla says, “Jude, those parts aren’t for girls like us.… We’re not girls who/glow in the spotlight.” “’But I want to be,” I say.’ (206)

Jude talks to her brother and although his life is full of danger, they are both “doing It” and “We are okay with learning our lines/because we are liking the script—/maybe, just maybe, we have both finally found roles/that make sense to us./Roles where we feel seen/as we truly are.” (324)

Jasmine Warga’s verse novel celebrates cultures and a strong, resilient, brave young adolescent who bridges them.

What happens when you have to leave your home to leave far away within another culture? How does that place become “home”?

When trouble spreads to Jude’s small city on the sea, a city formerly filled with tourists, and her older brother joins the revolution, seventh-grader Jude and her pregnant mother immigrate to America, leaving behind her Baba, his store, and her best friend to move in with her uncle, his American wife and their daughter. Life in Cincinnati is very different; Jude’s English is not as good as she had hoped and her popular seventh-grade cousin Sarah is afraid she will seem “weird,” like her new friend Layla whose parents came from Lebanon and wears a hajab.

Jude tries to assimilate but

“I am no longer/a girl./I am a Middle Eastern girl./A Syrian girl./A Muslim girl.

Americans love labels./They help them know what to expect./Sometimes, though,/I think labels stop them from/thinking.” (92)

As she learns more English, practicing slang with the four members of her ESL class, and becomes friends with Layla and Miles, a boy from her math class fascinated with stars and the galaxy, Jude misses Baba, Fatima, and Auntie Amal, and worries about Issa; however, she becomes closer to her aunt, speaks Arabic with her uncle, and starts thinking of the old house as home. Becoming a young woman, she begins wearing her scarves, although she has to convince her aunt that this is her choice.

Jude discovers that belonging is complicated. Layla tells her she is “lucky” that she comes from somewhere rather than being a Middle Eastern girl in America who, if she moved to Jordan, would be an American girl in the Middle East. “Lucky. I am learning how to say it/over and over again in English./I am learning how it tastes—/sweet with promise/and bitter with responsibility.” (168) Even the very American teen Sarah seems to want to embrace her other culture; she asks to learn Arabic and points out that, as cousins, they look much alike.

When Jude follows her brother’s wish that she be brave, she tries out for the school musical, even though Layla says, “Jude, those parts aren’t for girls like us.… We’re not girls who/glow in the spotlight.” “’But I want to be,” I say.’ (206)

Jude talks to her brother and although his life is full of danger, they are both “doing It” and “We are okay with learning our lines/because we are liking the script—/maybe, just maybe, we have both finally found roles/that make sense to us./Roles where we feel seen/as we truly are.” (324)

Jasmine Warga’s verse novel celebrates cultures and a strong, resilient, brave young adolescent who bridges them.

UNSETTLED by Reem Faruqi (verse novel)

In my last school,

I always knew

where to sit

and with who.

In my last school,

my name was known.

In my last school,

my voice was loud.

In this school,

I am mute.

In this school,

I am invisible. (91-92)

Nurah, her older brother Owais and their parents move from Karachi, Pakistan, to Peachtree, Georgia, for better schools and job security, leaving behind her three grandparents and her best friend Asna. The transition is not easy. In America they live in a hotel; Nurah’s mother seems to be fading, and her brother begins rebelling. When Nurah and Owais find a swimming pool at the Rec Center, they regain a bit of home. But Owais is an expert swimmer, appearing to fit in more effortlessly.

It is important to note

that my skin is

dark

like the heel of oatmeal bread

while Owais’s skin is

light

like the center of oatmeal bread.

We do not look alike

are not recognized

as brother and sister. (225)

The water is Nurah’s only friend, until

“Do you want to eat lunch with me?”

8 words that change my life. (110)

Nurah’s new friend Stahr also wears long sleeves, but not from Muslim modesty, and her secret bring the two girls and their mothers together.

And one day when Stahr is not at school at lunchtime, and Naurah is being bullied,

“I’m Destiny.

You can eat with us…” (216)

And then Owais is beat up by two of the boys on the swim team, jealous of his success, and Nurah feels guilty for not warning him to not go into the locker room. After his hospitalization, he gives up swimming.

he is

always in his room

lately,

because he is safer

on land

than in water (265)

And Nurah discovers another type of bullying when the boy she likes and his friends make fun of her visiting grandmother whose “mind becomes so tangled.”

I remember when my tongue

Betrayed me.

I remember

I need to

say something.

I go back in

to their laughter.

I find my voice

and

spit it out

“It’s not funny.”

The store gets

Very Quiet

and I feel

light again.

I grab Dadi’s ice cream.

I remember what hope

tastes like… (273)

When Nurah decides to begin wearing her hijab,

In the beginning

the looks of others spear me

but the more I wear it

the easier it becomes.

the more I wear it

the looks seem to

soften. (284)

Finally, at the masjid with Owais and his new friend Junaid

Today I wear my hijab

,

Tightly wrapped,

shimmery light blue,…

today when I look

in the mirror,

I think--

“Not bad.”

I feel prettier than I have

In a long time

And exactly where

I’m supposed to

be. (305)

A story of transition, new beginnings, the importance of friendship, and finding one’s voice and our “something unexpected,” Reem Faruqi’s verse novel is based on her childhood experiences as an immigrant living in Georgia.

In my last school,

I always knew

where to sit

and with who.

In my last school,

my name was known.

In my last school,

my voice was loud.

In this school,

I am mute.

In this school,

I am invisible. (91-92)

Nurah, her older brother Owais and their parents move from Karachi, Pakistan, to Peachtree, Georgia, for better schools and job security, leaving behind her three grandparents and her best friend Asna. The transition is not easy. In America they live in a hotel; Nurah’s mother seems to be fading, and her brother begins rebelling. When Nurah and Owais find a swimming pool at the Rec Center, they regain a bit of home. But Owais is an expert swimmer, appearing to fit in more effortlessly.

It is important to note

that my skin is

dark

like the heel of oatmeal bread

while Owais’s skin is

light

like the center of oatmeal bread.

We do not look alike

are not recognized

as brother and sister. (225)

The water is Nurah’s only friend, until

“Do you want to eat lunch with me?”

8 words that change my life. (110)

Nurah’s new friend Stahr also wears long sleeves, but not from Muslim modesty, and her secret bring the two girls and their mothers together.

And one day when Stahr is not at school at lunchtime, and Naurah is being bullied,

“I’m Destiny.

You can eat with us…” (216)

And then Owais is beat up by two of the boys on the swim team, jealous of his success, and Nurah feels guilty for not warning him to not go into the locker room. After his hospitalization, he gives up swimming.

he is

always in his room

lately,

because he is safer

on land

than in water (265)

And Nurah discovers another type of bullying when the boy she likes and his friends make fun of her visiting grandmother whose “mind becomes so tangled.”

I remember when my tongue

Betrayed me.

I remember

I need to

say something.

I go back in

to their laughter.

I find my voice

and

spit it out

“It’s not funny.”

The store gets

Very Quiet

and I feel

light again.

I grab Dadi’s ice cream.

I remember what hope

tastes like… (273)

When Nurah decides to begin wearing her hijab,

In the beginning

the looks of others spear me

but the more I wear it

the easier it becomes.

the more I wear it

the looks seem to

soften. (284)

Finally, at the masjid with Owais and his new friend Junaid

Today I wear my hijab

,

Tightly wrapped,

shimmery light blue,…

today when I look

in the mirror,

I think--

“Not bad.”

I feel prettier than I have

In a long time

And exactly where

I’m supposed to

be. (305)

A story of transition, new beginnings, the importance of friendship, and finding one’s voice and our “something unexpected,” Reem Faruqi’s verse novel is based on her childhood experiences as an immigrant living in Georgia.

EVERYTHING SAD IS UNTRUE by Daniel Nayeri (memoir)

Years ago I heard Tim O’Brien, author of The Things They Carried, tell an audience, “You don’t have to tell a true story to tell the truth.” When I facilitate memoir workshops, I advise writers that memoir is how the memoirist remembers and interprets events.

EVERYTHING SAD IS UNTRUE is the story of Khosrou Nayeri on his way to becoming Daniel Nayeri. It is the stories of his childhood in Iran, in Dubai, in a refugee “camp” in Italy, in his relocation home in Oklahoma; it is also the stories of the Persian and Iranian people and history. It is a recounting that flits from time to time and person to person and place to place, inviting readers to participate as we form a relationship with the storyteller.

This is a collection of stories reminiscent of 1001 Arabian Nights. In fact, Daniel frequently compares himself to Scheherazade, telling readers, “Every story is the sound of a storyteller begging to stay alive.” (59) The author further explains that, in his case, “You don’t get to choose what you remember. A patchwork memory is the shame of a refugee.” (49) and later explains, “Memories are just stories we tell ourselves, after all. (349)

Everything Sad is Untrue reminds me of my favorite children’s book Haroun and the Sea of Stories in which Salman Rushdie proves “the use of stories that aren’t even true,” a novel that likewise blends Eastern and Western cultures.

But the most important feature of this wonderful novel is the author’s voice which comes through on every page. As our storyteller discloses, “The point of Nights is that if you spend time with each other—if we really listen in the parlors of our minds and look at each other as we were meant to be seen—then we would fall in love.…The stories aren’t the thing. The thing is the story of the story. The spending of the time. The falling in love.” (301) And that is why I am not recounting a summary of this story as in many of my reviews. I fell in love with the telling of the story.

A book certainly deserving its 2021 Michael L. Printz award, an award which annually honors the best book written for teens, based entirely on its literary merit.

.

Years ago I heard Tim O’Brien, author of The Things They Carried, tell an audience, “You don’t have to tell a true story to tell the truth.” When I facilitate memoir workshops, I advise writers that memoir is how the memoirist remembers and interprets events.

EVERYTHING SAD IS UNTRUE is the story of Khosrou Nayeri on his way to becoming Daniel Nayeri. It is the stories of his childhood in Iran, in Dubai, in a refugee “camp” in Italy, in his relocation home in Oklahoma; it is also the stories of the Persian and Iranian people and history. It is a recounting that flits from time to time and person to person and place to place, inviting readers to participate as we form a relationship with the storyteller.

This is a collection of stories reminiscent of 1001 Arabian Nights. In fact, Daniel frequently compares himself to Scheherazade, telling readers, “Every story is the sound of a storyteller begging to stay alive.” (59) The author further explains that, in his case, “You don’t get to choose what you remember. A patchwork memory is the shame of a refugee.” (49) and later explains, “Memories are just stories we tell ourselves, after all. (349)

Everything Sad is Untrue reminds me of my favorite children’s book Haroun and the Sea of Stories in which Salman Rushdie proves “the use of stories that aren’t even true,” a novel that likewise blends Eastern and Western cultures.

But the most important feature of this wonderful novel is the author’s voice which comes through on every page. As our storyteller discloses, “The point of Nights is that if you spend time with each other—if we really listen in the parlors of our minds and look at each other as we were meant to be seen—then we would fall in love.…The stories aren’t the thing. The thing is the story of the story. The spending of the time. The falling in love.” (301) And that is why I am not recounting a summary of this story as in many of my reviews. I fell in love with the telling of the story.

A book certainly deserving its 2021 Michael L. Printz award, an award which annually honors the best book written for teens, based entirely on its literary merit.

.

MY FAMILY DIVIDED: One Girl's Journey of Home, Loss & Hope by Diane Guerrero (memoir)

"Suddenly we saw a white police van pull up. Seconds later, two guards herded some inmates out onto the curb. My mother was among them.." (124)

When Diane Guerrero was 14 years old, her undocumented immigrant parents were deported to Colombia. Her older step-brother having previously moved away, this left Diane, an American citizen, on her own in Boston, dependent on the charity of family friends. "Neither ICE nor the Massachusetts Department of Children and Families had contacted me. This meant that at fourteen, I'd been left on my own. Literally. The same authorities who deported my parents hadn't bothered to check whether I, a fourteen-year-old citizen of this country, would be left without family adult supervision, or even a home." (115)

An adaptation of her adult memoir, co-authored by Erica Moroz, describes the life of the television actress Before and After Deportation as she struggles with ambivalent feelings towards her parents, poverty, and depression. "[At my senior recital] I ended with a jazz standard called 'Poor Butterfly.' It's about this Japanese woman enchanted by an American man who never returns to be with her. I'd chosen it because it struck a powerful chord in me. The abandonment. The hoping and waiting and yearning for something that doesn't happen." (153)

But this is also the story of the 11.4 million unauthorized US immigrants (2018), 500,00 of whom were deported (2019), others who are living under the constant threat of deportation and a family divided.

"Suddenly we saw a white police van pull up. Seconds later, two guards herded some inmates out onto the curb. My mother was among them.." (124)

When Diane Guerrero was 14 years old, her undocumented immigrant parents were deported to Colombia. Her older step-brother having previously moved away, this left Diane, an American citizen, on her own in Boston, dependent on the charity of family friends. "Neither ICE nor the Massachusetts Department of Children and Families had contacted me. This meant that at fourteen, I'd been left on my own. Literally. The same authorities who deported my parents hadn't bothered to check whether I, a fourteen-year-old citizen of this country, would be left without family adult supervision, or even a home." (115)

An adaptation of her adult memoir, co-authored by Erica Moroz, describes the life of the television actress Before and After Deportation as she struggles with ambivalent feelings towards her parents, poverty, and depression. "[At my senior recital] I ended with a jazz standard called 'Poor Butterfly.' It's about this Japanese woman enchanted by an American man who never returns to be with her. I'd chosen it because it struck a powerful chord in me. The abandonment. The hoping and waiting and yearning for something that doesn't happen." (153)

But this is also the story of the 11.4 million unauthorized US immigrants (2018), 500,00 of whom were deported (2019), others who are living under the constant threat of deportation and a family divided.

WHEN STARS ARE SCATTERED by Victoria Jamieson and Omar Mohamed (graphic)

“No one chooses to be a refugee. To leave their homes, family, and country.” (Omar Mohamed’s Author’s Note) At least 79.5 million people around the world have been forced to flee their homes. Among them are nearly 26 million refugees, half of whom are under the age of 18. (UNHCR.org)

Omar and his younger brother Hassan spent 15 years in Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya, leaving their home in Somalia when Omar was 4 years old. Their father had been killed and mother left, not returning before the villagers were compelled to flee the violence, taking the boys with them. This is Omar and Hassan’s story, beginning after 7 years living in the camp with Fatuma, their appointed foster mother, also a refugee.

It is the story of Omar who was encouraged to begin school at age ten and found hope in education. Though it was challenging to take care of Hassan, chores, and studying, he earned his way into middle school and then high school.

It is the story of his brother Hassan who had seizures and did not speak but was kind to children and animals and watched over by the camp community.

It is the story of the girls of the camp, especially Nimo and Maryam, and the restrictions and expectations placed on girls by their society.

It is the story of the camp refugees and constant hunger, deprivation, and despair but also the joyful celebrations of holidays and traditions and the hope for reunification with family and resettlement in a safe country. And dreams.

“None of us ask to be born where we are, or how we are. The challenge of life is to make the most out of what you’ve been given. And despite all the things I don’t have…I have been given something very important. The love of others is a gift from God, and it shouldn’t be taken for granted.” (212)

Omar’s story, co-written and illustrated by Victoria Jamieson, is a graphic memoir that comes alive through the drawings. It includes an Afterword that takes readers from the story’s ending in 2009 to Omar and Hassan’s life today. This novel will be an important introduction to many readers to a life their peers may have experienced. Hopefully it is a story which will lead to understanding, compassion, and respect. As Omar’s middle school English teacher tells them, “Throughout your life, people may shout ugly words at you like, ‘Go home, refugee!’ or ‘You have no right to be here!’ When you meet these people, tell them to look at the stars, and how they move across the sky. No one tells a star to go home.” (120)

“No one chooses to be a refugee. To leave their homes, family, and country.” (Omar Mohamed’s Author’s Note) At least 79.5 million people around the world have been forced to flee their homes. Among them are nearly 26 million refugees, half of whom are under the age of 18. (UNHCR.org)

Omar and his younger brother Hassan spent 15 years in Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya, leaving their home in Somalia when Omar was 4 years old. Their father had been killed and mother left, not returning before the villagers were compelled to flee the violence, taking the boys with them. This is Omar and Hassan’s story, beginning after 7 years living in the camp with Fatuma, their appointed foster mother, also a refugee.

It is the story of Omar who was encouraged to begin school at age ten and found hope in education. Though it was challenging to take care of Hassan, chores, and studying, he earned his way into middle school and then high school.

It is the story of his brother Hassan who had seizures and did not speak but was kind to children and animals and watched over by the camp community.

It is the story of the girls of the camp, especially Nimo and Maryam, and the restrictions and expectations placed on girls by their society.

It is the story of the camp refugees and constant hunger, deprivation, and despair but also the joyful celebrations of holidays and traditions and the hope for reunification with family and resettlement in a safe country. And dreams.

“None of us ask to be born where we are, or how we are. The challenge of life is to make the most out of what you’ve been given. And despite all the things I don’t have…I have been given something very important. The love of others is a gift from God, and it shouldn’t be taken for granted.” (212)

Omar’s story, co-written and illustrated by Victoria Jamieson, is a graphic memoir that comes alive through the drawings. It includes an Afterword that takes readers from the story’s ending in 2009 to Omar and Hassan’s life today. This novel will be an important introduction to many readers to a life their peers may have experienced. Hopefully it is a story which will lead to understanding, compassion, and respect. As Omar’s middle school English teacher tells them, “Throughout your life, people may shout ugly words at you like, ‘Go home, refugee!’ or ‘You have no right to be here!’ When you meet these people, tell them to look at the stars, and how they move across the sky. No one tells a star to go home.” (120)

EFREN DIVIDED by Ernesto Cisneros

In the United States today, more than 16.7 million people share a home with at least one family member, often a parent, who is undocumented. Roughly six million of these people are children under the age of 18. As of 2018, 4.4 million children under the age of 18 who are United States citizens lived with at least one undocumented parent. Consequently, immigration enforcement actions—and the ever-present threat of enforcement action—have significant physical, emotional, developmental, and economic repercussions for millions of children across the country. Deportations of parents and other family members have serious consequences that affect children—including U.S.-citizen children—and extend to entire communities and the country as a whole. (American Immigration Council, “U.S. Citizen Children Impacted by Immigrant Enforcement Fact Sheet,” June 2021)

-------------

Efren Nava lived with his young twin siblings and two undocumented parents. Poor and hardworking, living in a 1-room apartment, they were proud and quite happy. Ama was Efren’s Soperwoman, making delicious meals out of almost nothing. The entire community was living under the threat of ICE raids.

Meanwhile, Efren navigated middle school and friends. David, his best friend and the only white kid at school (“You taught me that the color of my skin doesn’t matter” [246]), decides to run for Student Council President with Efren helping him on his campaign even though Efren know that his opponent, the serious, intelligent Jennifer Huerta, would be a better choice than David.

And then Ama is deported. Apa begins working two jobs to try to earn enough money to hire a coyote to bring her back, and Efren has to take care of the twins, get food (resorting a stealing food from the cafeteria trash cans), make meals, and try to keep up with his school work, as well as keep their family’s secret.

“Efren missed the old days, back when his neighborhood block made up his entire world, back when all he worried about was whether to play it safe with a game of marbles or brave a match of chicken fights along the monkey bars.” (75)

When Jennifer’s mother is deported and Jennifer goes to Mexico with her, Efren decides to run in the election to help further her ideas about immigration awareness; he keeps his reasons secret from his best friend and loses David’s friendship.

When Efren accompanies his father to the border and, as a U.S.-born citizen, crosses the border to meet his mother and give her the money she needs to be brought back, he meets Lalo, a taxi driver who was taken from his family and deported many years ago. Lalo keeps Efren safe under he meets Ama and he arranges for help that can be trusted. Efren returns home to await his mother’s return but the short trip has given him his other culture.

“A strange mix of sadness and pride overtook him., and for the first time in his entire life, he finally felt connected to his Mexican side. Everywhere he’d been, Efren had witnessed signs of courage, people no different from himself refusing to give up.…he’d been born Mexican American. Only he’d forgotten about the Mexican part.” (208)

Navigating the difficulties of living with undocumented parents and poverty, Efren also experiences many acts of kindness from a variety of people—teachers, peers, friends, neighbors, in this story which will represent and bring to notice challenges that many of our students or their peers in other communities are experiencing.

In the United States today, more than 16.7 million people share a home with at least one family member, often a parent, who is undocumented. Roughly six million of these people are children under the age of 18. As of 2018, 4.4 million children under the age of 18 who are United States citizens lived with at least one undocumented parent. Consequently, immigration enforcement actions—and the ever-present threat of enforcement action—have significant physical, emotional, developmental, and economic repercussions for millions of children across the country. Deportations of parents and other family members have serious consequences that affect children—including U.S.-citizen children—and extend to entire communities and the country as a whole. (American Immigration Council, “U.S. Citizen Children Impacted by Immigrant Enforcement Fact Sheet,” June 2021)

-------------

Efren Nava lived with his young twin siblings and two undocumented parents. Poor and hardworking, living in a 1-room apartment, they were proud and quite happy. Ama was Efren’s Soperwoman, making delicious meals out of almost nothing. The entire community was living under the threat of ICE raids.

Meanwhile, Efren navigated middle school and friends. David, his best friend and the only white kid at school (“You taught me that the color of my skin doesn’t matter” [246]), decides to run for Student Council President with Efren helping him on his campaign even though Efren know that his opponent, the serious, intelligent Jennifer Huerta, would be a better choice than David.

And then Ama is deported. Apa begins working two jobs to try to earn enough money to hire a coyote to bring her back, and Efren has to take care of the twins, get food (resorting a stealing food from the cafeteria trash cans), make meals, and try to keep up with his school work, as well as keep their family’s secret.

“Efren missed the old days, back when his neighborhood block made up his entire world, back when all he worried about was whether to play it safe with a game of marbles or brave a match of chicken fights along the monkey bars.” (75)

When Jennifer’s mother is deported and Jennifer goes to Mexico with her, Efren decides to run in the election to help further her ideas about immigration awareness; he keeps his reasons secret from his best friend and loses David’s friendship.

When Efren accompanies his father to the border and, as a U.S.-born citizen, crosses the border to meet his mother and give her the money she needs to be brought back, he meets Lalo, a taxi driver who was taken from his family and deported many years ago. Lalo keeps Efren safe under he meets Ama and he arranges for help that can be trusted. Efren returns home to await his mother’s return but the short trip has given him his other culture.

“A strange mix of sadness and pride overtook him., and for the first time in his entire life, he finally felt connected to his Mexican side. Everywhere he’d been, Efren had witnessed signs of courage, people no different from himself refusing to give up.…he’d been born Mexican American. Only he’d forgotten about the Mexican part.” (208)

Navigating the difficulties of living with undocumented parents and poverty, Efren also experiences many acts of kindness from a variety of people—teachers, peers, friends, neighbors, in this story which will represent and bring to notice challenges that many of our students or their peers in other communities are experiencing.

FRONT DESK by Kelly Yang

Front Desk’s ten-year-old Mia moves to the head of my “Strong Girls in MG/YA Lit” list as she becomes an activist and champion of those who cannot, or will not, stand up for themselves [“You don’t get it, kid. I’ve been fighting my whole life. I’m done. It’s no use fighting—people are gonna be the way they’re gonna be” (105)], teaches others the wrongs of prejudice and injustice, and forms a community from her neighbors, patrons, and fellow immigrants.

Mia and her parents emigrated from China to the United States for a more “free” life. In China her parents were professionals; in America they feel lucky to find a job managing a motel. But the owner, Mr. Yao, is unkind, unjust, cheap, and prejudiced. He reduces their salaries until they are working for lodging and a life of poverty. And while this is a novel about Mia who manages the front desk and helps her parents temporarily hide other Chinese immigrants who have been mistreated, it is really a novel of culture, prejudice, bullying, community, and, most of all, the power of writing. “It was the most incredible feeling ever, knowing that something I wrote actually changed someone’s life.” (218)

In America there are two roller coasters, and people are born to a life on one or the other, but Mia and her friend Lupe, whose family came from Mexico, have decided to break that cycle. Although bullied in school and warned by her mother that she will never be a “native” English writer, Mia develops her writing skills to help Hank gain employment after a wrongful arrest, free “Uncle” Zhang whose ID and passport were being held by his employer, share her story with her teacher and classmates, and finally persuade friends and strangers to take a chance on her family.

Mia is a representative of the “nearly twenty million immigrant children currently living in the United States, 30 percent of whom are living at or below poverty.” (Author’s Note). As such, this book will serve as a mirror for many readers, a map for others looking for ways to navigate young adolescent life, especially in a new culture, and as a window for those who will learn empathy for others they may see as different. Author Kelly Yang also shares the autobiographical elements of the novel in her Author’s Note.

Front Desk, with its very short chapters and challenging topics would be a meaningful and effective 10-minute read-aloud to begin Grade 4-7 daily reading workshop focus lessons. I would suggest projecting Mia’s letters since they show her revisions as she seeks to improve her language skills and word choices.

Front Desk’s ten-year-old Mia moves to the head of my “Strong Girls in MG/YA Lit” list as she becomes an activist and champion of those who cannot, or will not, stand up for themselves [“You don’t get it, kid. I’ve been fighting my whole life. I’m done. It’s no use fighting—people are gonna be the way they’re gonna be” (105)], teaches others the wrongs of prejudice and injustice, and forms a community from her neighbors, patrons, and fellow immigrants.

Mia and her parents emigrated from China to the United States for a more “free” life. In China her parents were professionals; in America they feel lucky to find a job managing a motel. But the owner, Mr. Yao, is unkind, unjust, cheap, and prejudiced. He reduces their salaries until they are working for lodging and a life of poverty. And while this is a novel about Mia who manages the front desk and helps her parents temporarily hide other Chinese immigrants who have been mistreated, it is really a novel of culture, prejudice, bullying, community, and, most of all, the power of writing. “It was the most incredible feeling ever, knowing that something I wrote actually changed someone’s life.” (218)

In America there are two roller coasters, and people are born to a life on one or the other, but Mia and her friend Lupe, whose family came from Mexico, have decided to break that cycle. Although bullied in school and warned by her mother that she will never be a “native” English writer, Mia develops her writing skills to help Hank gain employment after a wrongful arrest, free “Uncle” Zhang whose ID and passport were being held by his employer, share her story with her teacher and classmates, and finally persuade friends and strangers to take a chance on her family.

Mia is a representative of the “nearly twenty million immigrant children currently living in the United States, 30 percent of whom are living at or below poverty.” (Author’s Note). As such, this book will serve as a mirror for many readers, a map for others looking for ways to navigate young adolescent life, especially in a new culture, and as a window for those who will learn empathy for others they may see as different. Author Kelly Yang also shares the autobiographical elements of the novel in her Author’s Note.

Front Desk, with its very short chapters and challenging topics would be a meaningful and effective 10-minute read-aloud to begin Grade 4-7 daily reading workshop focus lessons. I would suggest projecting Mia’s letters since they show her revisions as she seeks to improve her language skills and word choices.

THREE KEYS (Front Desk #2) by Kelly Yang

“I thought about Lupe’s words for a long time, thinking of how different and similar the two of us were. We were both girls with big hopes and dreams. But because of one piece of paper, we were on two different sides of the law. I didn’t really understand before what that paper meant. But now, I was starting to realize, it meant the difference between living in freedom and living in fear.” (171)

Sixth grader Mia continues her crusade for social justice in this sequel to Front Desk (https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/2462532950). Mia and her parents are now owners of the Calivista Motel where, with the help of the weeklies, especially Hank, they rent rooms, hold “How to Navigate America” classes for immigrants, and try to earn enough to pay dividends to their investors and possibly someday ending Mia’s mother’s endless room cleaning.

Mia again sees racism and discrimination all around her, even among her classmates, and she forms Kids for Kids, a new club for those who also feel outside the mainstream. With Proposition 187* coming up for a vote in California, many of Mia’s undocumented friends, including her best friend Lupe, fear for their futures. And they become activists. “’That’s the worst.’ Jorge shook his head. ‘The people who just watch and don’t do anything.’” (80)

When Lupe’s mother goes back to Mexico for a family funeral and her father is imprisoned, the girls and the motel family gather forces to oppose Jose’s deportation, Prop 187, and racism. Mia fights in the way she knows—writing letters to the editor. But she recognizes that she has certain privileges as an immigrant with papers. “I realized something that I never thought of before: that the thing I had been relying on to voice my complaints and frustrations, my outlet and most powerful ammunition, wasn’t available to everyone. There were certain things you needed to write letters, besides just a pen.” (108)

As the Calivista community becomes even more inclusive with a “Welcome, Immigrants” sign and bunk beds for cheaper rates and Mia and Lupe gain a few converts—Mrs. Welch, their teacher; Jason Yao, former enemy, and finally even his father, they have hope for the future.

This is an important novel for middle grade students who need to see their lives and lives of those they may encounter in person or on the news reflected in story and to see the strength and power they can have and the difference they can make.

*Proposition 187 sought, among other things, to require police, health care professionals and teachers to verify and report the immigration status of all individuals, including children. The stated purpose was to make immigrants residing in the country without legal permission ineligible for public social services, public health care services, and public education at elementary, secondary, and post-secondary levels. Shortly after the law was passed in November 1994, a permanent injunction was issued against its implementation; Prop 187 was formally voided on July 29, 1999.

“I thought about Lupe’s words for a long time, thinking of how different and similar the two of us were. We were both girls with big hopes and dreams. But because of one piece of paper, we were on two different sides of the law. I didn’t really understand before what that paper meant. But now, I was starting to realize, it meant the difference between living in freedom and living in fear.” (171)

Sixth grader Mia continues her crusade for social justice in this sequel to Front Desk (https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/2462532950). Mia and her parents are now owners of the Calivista Motel where, with the help of the weeklies, especially Hank, they rent rooms, hold “How to Navigate America” classes for immigrants, and try to earn enough to pay dividends to their investors and possibly someday ending Mia’s mother’s endless room cleaning.

Mia again sees racism and discrimination all around her, even among her classmates, and she forms Kids for Kids, a new club for those who also feel outside the mainstream. With Proposition 187* coming up for a vote in California, many of Mia’s undocumented friends, including her best friend Lupe, fear for their futures. And they become activists. “’That’s the worst.’ Jorge shook his head. ‘The people who just watch and don’t do anything.’” (80)

When Lupe’s mother goes back to Mexico for a family funeral and her father is imprisoned, the girls and the motel family gather forces to oppose Jose’s deportation, Prop 187, and racism. Mia fights in the way she knows—writing letters to the editor. But she recognizes that she has certain privileges as an immigrant with papers. “I realized something that I never thought of before: that the thing I had been relying on to voice my complaints and frustrations, my outlet and most powerful ammunition, wasn’t available to everyone. There were certain things you needed to write letters, besides just a pen.” (108)

As the Calivista community becomes even more inclusive with a “Welcome, Immigrants” sign and bunk beds for cheaper rates and Mia and Lupe gain a few converts—Mrs. Welch, their teacher; Jason Yao, former enemy, and finally even his father, they have hope for the future.

This is an important novel for middle grade students who need to see their lives and lives of those they may encounter in person or on the news reflected in story and to see the strength and power they can have and the difference they can make.

*Proposition 187 sought, among other things, to require police, health care professionals and teachers to verify and report the immigration status of all individuals, including children. The stated purpose was to make immigrants residing in the country without legal permission ineligible for public social services, public health care services, and public education at elementary, secondary, and post-secondary levels. Shortly after the law was passed in November 1994, a permanent injunction was issued against its implementation; Prop 187 was formally voided on July 29, 1999.

GRINGOLANDIA by Lyn Miller-Lachmann

"The bigger the issue, the smaller you write."- Richard Price.

We read for many reasons but one essential purpose is to learn about our world, including its history, and develop empathy for others. I found that, by teaching a social justice course through novels, my 8th graders learned about the effects of history on others, even others their age.

Gringolandia shares the story of high school student Daniel, a refugee from Chile's Pinochet regime, his activist "gringo" girlfriend Courtney, and Daniel's father who has just been released from years of torture in a Chilean prison and joins his family in Gringolandia.

Spanning 1980-1991 this novel would be a valuable addition to a Social Justice or Social Studies curriculum or in my personal case, a good read to learn a history generally not covered in curriculum.

"The bigger the issue, the smaller you write."- Richard Price.

We read for many reasons but one essential purpose is to learn about our world, including its history, and develop empathy for others. I found that, by teaching a social justice course through novels, my 8th graders learned about the effects of history on others, even others their age.

Gringolandia shares the story of high school student Daniel, a refugee from Chile's Pinochet regime, his activist "gringo" girlfriend Courtney, and Daniel's father who has just been released from years of torture in a Chilean prison and joins his family in Gringolandia.

Spanning 1980-1991 this novel would be a valuable addition to a Social Justice or Social Studies curriculum or in my personal case, a good read to learn a history generally not covered in curriculum.

I AM NOT ALONE by Francisco Stork

Usually when I finish a novel, my book is full of stickies marking quotes I want to use in my review. However, halfway through I Am Not Alone, I realized that I hadn’t marked any passages, too intent in following Alberto and Grace’s journeys to justice, maybe even salvation, and possibly each other—and solving a mystery.

Alberto is an undocumented teen immigrant from Mexico who lives with his sister and her baby. He works very hard to keep Lupe recovered from her drug addiction and tries to convince her to leave Wayne, her abusive boyfriend who is the married father of her baby, the owner of their apartment, and Alberto’s boss. He also has quit high school to work many hours to send most of his $7/hour paycheck to his mother and sisters in Mexico. Adding to his challenges, Alberto is struggling with the onset of schizophrenia and hears a voice in his head, which he refers to as “Captain America,” that prescribes his actions and constantly gives him critical thoughts about himself.

I first met Alberto and Captain America in Stork's 2018 short story “Captain, My Captain” in UNBROKEN: Stories Starring Disabled Teens, a story limited to Alberto’s perspective.

In this novel, readers are also introduced to Grace, a high school senior. Grace is a high achiever and thinks she has her life plan figured out: boyfriend Michael, high school valedictorian, Princeton college, and then medical school to become a pyschiatrist like her father. Still reeling from her father leaving and her parents’ divorce, Alberto comes to clean her windows after a paint job, and Grace’s world falls apart as she begins to question her goals and even the meaning of love.

Readers also meet Grace’s supportive mother, her paternal grandfather and young cousin Benny, and Alberto’s house painting co-workers Jimbo and the drug-dealing Lucas.

Then the elderly resident of the apartment that Alberto, Jimbo, and Lucas were painting is murdered, and the evidence points to Alberto who is afraid that Captain America made him kill the woman. As Alberto looks for clues and Grace separately tries to prove his innocence, involving her grandfather, Benny, and their rabbi, and even the police detective, Alberto—and Grace—learn the meaning of friendship and community and believing in oneself and others.

This is an important novel about mental illness, the role religion can play, and unrestricted friendship for those teens who may just need this story to accept themselves or their peers. It also highlights the challenges faced by undocumented youth.

Usually when I finish a novel, my book is full of stickies marking quotes I want to use in my review. However, halfway through I Am Not Alone, I realized that I hadn’t marked any passages, too intent in following Alberto and Grace’s journeys to justice, maybe even salvation, and possibly each other—and solving a mystery.

Alberto is an undocumented teen immigrant from Mexico who lives with his sister and her baby. He works very hard to keep Lupe recovered from her drug addiction and tries to convince her to leave Wayne, her abusive boyfriend who is the married father of her baby, the owner of their apartment, and Alberto’s boss. He also has quit high school to work many hours to send most of his $7/hour paycheck to his mother and sisters in Mexico. Adding to his challenges, Alberto is struggling with the onset of schizophrenia and hears a voice in his head, which he refers to as “Captain America,” that prescribes his actions and constantly gives him critical thoughts about himself.

I first met Alberto and Captain America in Stork's 2018 short story “Captain, My Captain” in UNBROKEN: Stories Starring Disabled Teens, a story limited to Alberto’s perspective.

In this novel, readers are also introduced to Grace, a high school senior. Grace is a high achiever and thinks she has her life plan figured out: boyfriend Michael, high school valedictorian, Princeton college, and then medical school to become a pyschiatrist like her father. Still reeling from her father leaving and her parents’ divorce, Alberto comes to clean her windows after a paint job, and Grace’s world falls apart as she begins to question her goals and even the meaning of love.

Readers also meet Grace’s supportive mother, her paternal grandfather and young cousin Benny, and Alberto’s house painting co-workers Jimbo and the drug-dealing Lucas.

Then the elderly resident of the apartment that Alberto, Jimbo, and Lucas were painting is murdered, and the evidence points to Alberto who is afraid that Captain America made him kill the woman. As Alberto looks for clues and Grace separately tries to prove his innocence, involving her grandfather, Benny, and their rabbi, and even the police detective, Alberto—and Grace—learn the meaning of friendship and community and believing in oneself and others.

This is an important novel about mental illness, the role religion can play, and unrestricted friendship for those teens who may just need this story to accept themselves or their peers. It also highlights the challenges faced by undocumented youth.

ILLEGAL by Francisco Stork

Francisco’s Stork’s 2017 novel Disappeared takes place in Juarez, Mexico, and depicts sex trafficking, the cartel, murder, poverty, betrayal, abandonment.

Sara Zapata, a young reporter for a local paper, is committed to finding and saving the young women she learns are being kidnapped, including her best friend Linda, despite the warnings of her boss and the threats to herself and her family.

Sara’s younger brother Emiliano, whose life has been affected by his father’s abandonment—of the family and his native Mexico—is looking for a better life, for ways to make money to pay the family bills and win the love of his wealthy girlfriend.

The siblings find in following their consciences, helping others, and making moral choices, they need to do what is right—not what is easy or even safe, and must sacrifice, or revise, their personal goals. To save their lives, Sara and Emiliano escape to the United States to find a better life and to bring the cartel who is trafficking the women to justice. They cross the border and are attacked in the dessert.

Sara turns herself over to the authorities, certain that she meets the requirements for asylum but, as her time in the detention facility grows longer and she observes women being mistreated and deported for no reason, she questions her assumptions. “I imagined that all I had to do was show the authorities the evidence of actual persecution, of actual threats, such as people machine-gunning our house in Juarez.… I saw my case as fitting within the legal reasons for asylum under the law of the United States. Was I wrong about the United States?” (31) She finds, “The whole process of who gets asylum and who gets detained, who gets a bond and who gets released, who gets a visa and who gets deported. I mean, it’s not as rational as I imagined it would be.” (34)

Meanwhile Emiliano enters the country illegally and goes to Chicago with his father, planning to turn Linda’s evidence against the cartel over to the proper authorities. He also finds America to be less than welcoming. As he tells his new friend Aniela, “I think that in Mexico I feel like I belong all the time. I never feel not wanted like I do here sometimes. Here I’m always looking over my shoulder even when no one is there.…knowing that you belong and are wanted is major.” (251)

When Sara’s attorney is killed and she is placed in solitary confinement and Emiliano finds he can no longer trust his father, tensions escalate. A study of government corruption and the asylum process, this sequel to Disappeared is a thriller that will hook the most reluctant adolescent reader. Enough background is given in Illegal that it may not be completely necessary to read Disappeared first but it would surely enhance the reading.

Francisco’s Stork’s 2017 novel Disappeared takes place in Juarez, Mexico, and depicts sex trafficking, the cartel, murder, poverty, betrayal, abandonment.

Sara Zapata, a young reporter for a local paper, is committed to finding and saving the young women she learns are being kidnapped, including her best friend Linda, despite the warnings of her boss and the threats to herself and her family.

Sara’s younger brother Emiliano, whose life has been affected by his father’s abandonment—of the family and his native Mexico—is looking for a better life, for ways to make money to pay the family bills and win the love of his wealthy girlfriend.

The siblings find in following their consciences, helping others, and making moral choices, they need to do what is right—not what is easy or even safe, and must sacrifice, or revise, their personal goals. To save their lives, Sara and Emiliano escape to the United States to find a better life and to bring the cartel who is trafficking the women to justice. They cross the border and are attacked in the dessert.

Sara turns herself over to the authorities, certain that she meets the requirements for asylum but, as her time in the detention facility grows longer and she observes women being mistreated and deported for no reason, she questions her assumptions. “I imagined that all I had to do was show the authorities the evidence of actual persecution, of actual threats, such as people machine-gunning our house in Juarez.… I saw my case as fitting within the legal reasons for asylum under the law of the United States. Was I wrong about the United States?” (31) She finds, “The whole process of who gets asylum and who gets detained, who gets a bond and who gets released, who gets a visa and who gets deported. I mean, it’s not as rational as I imagined it would be.” (34)

Meanwhile Emiliano enters the country illegally and goes to Chicago with his father, planning to turn Linda’s evidence against the cartel over to the proper authorities. He also finds America to be less than welcoming. As he tells his new friend Aniela, “I think that in Mexico I feel like I belong all the time. I never feel not wanted like I do here sometimes. Here I’m always looking over my shoulder even when no one is there.…knowing that you belong and are wanted is major.” (251)

When Sara’s attorney is killed and she is placed in solitary confinement and Emiliano finds he can no longer trust his father, tensions escalate. A study of government corruption and the asylum process, this sequel to Disappeared is a thriller that will hook the most reluctant adolescent reader. Enough background is given in Illegal that it may not be completely necessary to read Disappeared first but it would surely enhance the reading.

MARIO'S NOTEBOOK by Mary Atkinson

Traditionally, the United States has long been the global leader in resettling refugees, strictly defined as people forced to flee their home country to escape war, persecution or violence. (https://www.smithsonianmag.com) The number of refugee children has increased over the past decade. With approximately 350 refugee resettlement agencies spread throughout nearly all 50 states, refugee children can be found in classrooms throughout the country. Together with immigrants, these newcomer children make up one in five children in the U.S. (https://brycs.org) Many children look around their classrooms and wonder, Who are these kids and why are they here? Some parrot opinions heard from the adults in their lives—both positive and negative.

Mario, a survivor of the Salvadoran Civil War of the 1980s, was one of those newcomers. Mario witnessed his father, a journalist, being taken away from their home. “All I can do is watch. Watch as the soldiers blindfold Papa. Watch as they shove him out the door. Watch as Mama collapses to the floor.” (21) He later learns of the death of his father, killed by the soldiers.

Mario with his mother and younger brother are smuggled to the United States where they are given an apartment, food, clothes, and toys, and Mario wonders, “Will anything in my life ever feel right?” (44) Mario is enrolled in fifth grade where all the children accept him, especially twins William and LaShaunda, except for the class bully Randall. When discussing an article on deportation in social studies class, Randall has no trouble sharing his opinions. “My father says people like this should go back to their own countries. We didn’t ask them to come here.” (83)

And after a small incident in his father’s store, Randall threatens Mario and his family. “My father could get you kicked out of the country, you know.” (79)

Mario struggles with feelings of betrayal by his father’s political articles, actions which led to their current situation. When he finally has the courage to read the notebook his father left him—and the article his father signaled him to pull from the typewriter the night he was taken—he reaches understanding of his father’s heroism and the importance of letting the world know of the war, persecution, and violence occurring in his country.

Mary Atkinson’s short novel is not only a good story with engaging, well-developed characters, can serve as an effective tool for generating important conversations about refugee admissions and resettlement and the importance of opening our hearts (and our borders).

Traditionally, the United States has long been the global leader in resettling refugees, strictly defined as people forced to flee their home country to escape war, persecution or violence. (https://www.smithsonianmag.com) The number of refugee children has increased over the past decade. With approximately 350 refugee resettlement agencies spread throughout nearly all 50 states, refugee children can be found in classrooms throughout the country. Together with immigrants, these newcomer children make up one in five children in the U.S. (https://brycs.org) Many children look around their classrooms and wonder, Who are these kids and why are they here? Some parrot opinions heard from the adults in their lives—both positive and negative.

Mario, a survivor of the Salvadoran Civil War of the 1980s, was one of those newcomers. Mario witnessed his father, a journalist, being taken away from their home. “All I can do is watch. Watch as the soldiers blindfold Papa. Watch as they shove him out the door. Watch as Mama collapses to the floor.” (21) He later learns of the death of his father, killed by the soldiers.

Mario with his mother and younger brother are smuggled to the United States where they are given an apartment, food, clothes, and toys, and Mario wonders, “Will anything in my life ever feel right?” (44) Mario is enrolled in fifth grade where all the children accept him, especially twins William and LaShaunda, except for the class bully Randall. When discussing an article on deportation in social studies class, Randall has no trouble sharing his opinions. “My father says people like this should go back to their own countries. We didn’t ask them to come here.” (83)

And after a small incident in his father’s store, Randall threatens Mario and his family. “My father could get you kicked out of the country, you know.” (79)

Mario struggles with feelings of betrayal by his father’s political articles, actions which led to their current situation. When he finally has the courage to read the notebook his father left him—and the article his father signaled him to pull from the typewriter the night he was taken—he reaches understanding of his father’s heroism and the importance of letting the world know of the war, persecution, and violence occurring in his country.

Mary Atkinson’s short novel is not only a good story with engaging, well-developed characters, can serve as an effective tool for generating important conversations about refugee admissions and resettlement and the importance of opening our hearts (and our borders).

OUT OF NOWHERE by Maria Padian

“Things get a little more complicated when you know somebody’s story.…It’s hard to fear someone, or be cruel to them, when you know their story.”

The majority of the 21.3 million refugees worldwide in 2016 were from Syria, Afghanistan and Somalia. The United States resettled 84,994 refugees. Together with immigrants, refugee children make up one in five children in the U.S. More than half the Syrian refugees who were resettled in the U.S. between October 2010 and November 2015 are under the age of 20.

.

In Out of Nowhere, narrator Tom Bouchard is a high school senior. He is a soccer player, top of his class academically, and well-liked. He lives in Maine in a town that has become a secondary migration location for Somali refugees. These Somali students are trying to navigate high school without many benefits, including the English language. They face hostility from many of their fellow classmates and the townspeople, including the mayor; one teacher, at the request of students, permits only English to be spoken in her classroom. When four Somali boys join the soccer team, turning it into a winning team, and when he is forced to complete volunteer hours at the K Street Center where he tutors a young Somali boy and works with a female Somali classmate, Tom learns at least a part of their stories.

Tom fights bigotry, especially that of his girlfriend—now ex-girlfriend, but he still doesn’t comprehend the complexity of the beliefs, customs, and traditions of his new friends and his actions have negative consequences for all involved. While trying to defend the truth, Tom learns a valuable lesson, “Truth is a difficult word. One person’s truth is another person’s falsehood. People believe what appears to be true and what they feel is true.”

I was teaching a unit on 9/11 a few years ago, and one of the students said, “Why do we have to read about this? It is history; it’s over.” One continuing and even escalating consequence of the events of 9/11, especially on young people, is Islamophobia. A 2015 report by the California chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations found 50 percent of Muslim students surveyed were subjected to mean comments or rumors because of their religion. Students need to read novels, such as Out of Nowhere, Bifocal, The Lines We Cross, Watched, and Amina’s Voice, to know the stories of many refugees, adolescent Muslim refugees in particular. Two thousand seven hundred seventy-five Somali refugees arrived in the United States between October 1 and December 7 of 2016.

“Things get a little more complicated when you know somebody’s story.…It’s hard to fear someone, or be cruel to them, when you know their story.”

The majority of the 21.3 million refugees worldwide in 2016 were from Syria, Afghanistan and Somalia. The United States resettled 84,994 refugees. Together with immigrants, refugee children make up one in five children in the U.S. More than half the Syrian refugees who were resettled in the U.S. between October 2010 and November 2015 are under the age of 20.

.

In Out of Nowhere, narrator Tom Bouchard is a high school senior. He is a soccer player, top of his class academically, and well-liked. He lives in Maine in a town that has become a secondary migration location for Somali refugees. These Somali students are trying to navigate high school without many benefits, including the English language. They face hostility from many of their fellow classmates and the townspeople, including the mayor; one teacher, at the request of students, permits only English to be spoken in her classroom. When four Somali boys join the soccer team, turning it into a winning team, and when he is forced to complete volunteer hours at the K Street Center where he tutors a young Somali boy and works with a female Somali classmate, Tom learns at least a part of their stories.

Tom fights bigotry, especially that of his girlfriend—now ex-girlfriend, but he still doesn’t comprehend the complexity of the beliefs, customs, and traditions of his new friends and his actions have negative consequences for all involved. While trying to defend the truth, Tom learns a valuable lesson, “Truth is a difficult word. One person’s truth is another person’s falsehood. People believe what appears to be true and what they feel is true.”