- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

- Asian, Asian-American

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

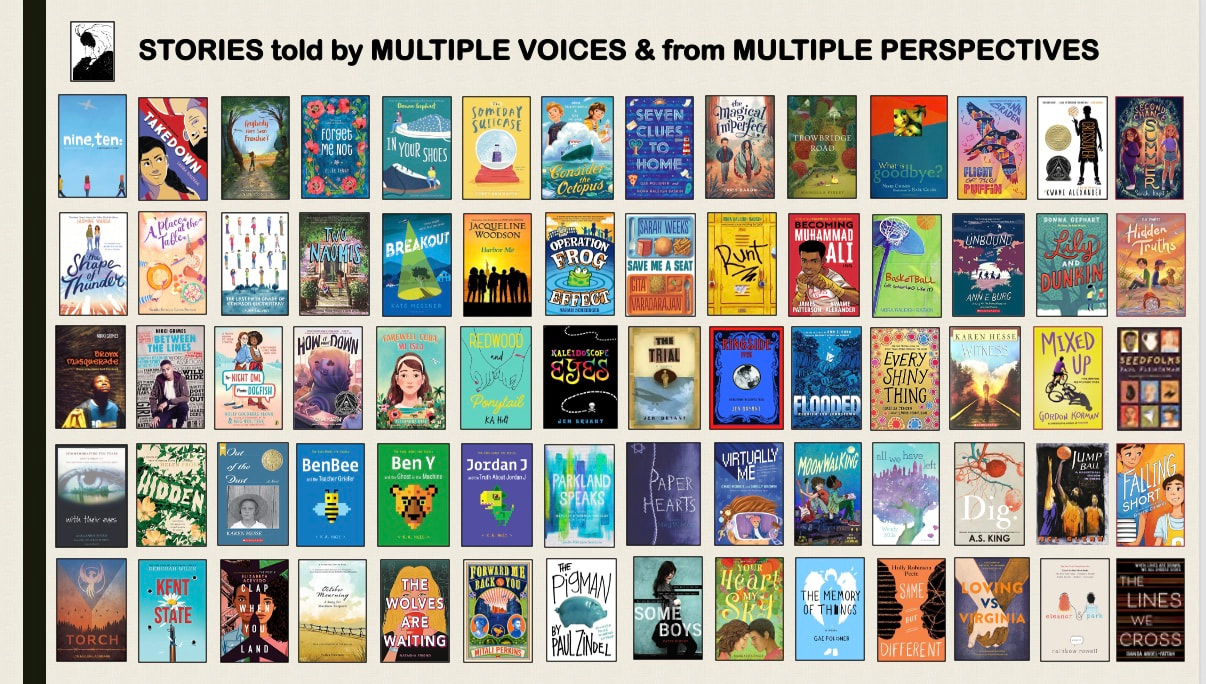

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

In most cases I only taught one whole-class novel each year. I began my year with short stories to teach/review literary elements and reading strategies and then we put it all together with a novel, following with 1-2 rounds of book clubs ad then independent self -selected reading, many times on a common topic or genre or format. When choosing a whole-class novel, I chose one that all my readers could read—with a little support from the class—and that would interest most readers. The most important criteria was that that book featured multiple main characters, ideally male and female, and diverse voices and perspectives.

The narrator controls the story we hear (or read); perspective determines what the listener is led to discover/encounter. Each person experiences events in different ways, and it is individual interpretations that are communicated.

Appreciating that every story may be seen from a variety of perspectives and lead to a variety of interpretations is an important step towards empathy, tolerance, and respect—crucial for our students to learn to broaden their limited points of view. It is vital that our students understand that there is never just one story; there are not even two sides to a story—a right side and a wrong side. There can be numerous versions of a story or multiple voices that need to tell each part of a story.

In literary works diverse voices relate a story from differing perspectives, presenting the same events with dissimilar perceptions; in other instances numerous narrators contribute to the movement of a story, one at a time. Multiple points of views show the reader what the various characters are thinking and feeling or how they individually view events and other characters.

For many years, my eighth graders read Paul Zindel’s The Pigman, considered one of the first “adolescent literature” novels. The novel was written for adolescents, featuring adolescents, and written from an adolescent point of view. In the novel sophomores John and Lorraine befriend a lonely elderly neighbor, Angelo Pignati, and take advantage of his many kindnesses. I think what captivated both my male and female readers was the way alternating chapters were narrated by John and Lorraine, allowing readers to not only become familiar with each character but to perceive their differing perspectives on situations.

Some of my favorite novels feature multiple, diverse voices many times alternating narrators. Some are written by two authors, each writing one voice,; some are written in dual formats, such as free verse for one character and prose for the other. And some stories are told through a multiplicity of voices. And some present two timelines.

My more recently-read are reviewed below.

The narrator controls the story we hear (or read); perspective determines what the listener is led to discover/encounter. Each person experiences events in different ways, and it is individual interpretations that are communicated.

Appreciating that every story may be seen from a variety of perspectives and lead to a variety of interpretations is an important step towards empathy, tolerance, and respect—crucial for our students to learn to broaden their limited points of view. It is vital that our students understand that there is never just one story; there are not even two sides to a story—a right side and a wrong side. There can be numerous versions of a story or multiple voices that need to tell each part of a story.

In literary works diverse voices relate a story from differing perspectives, presenting the same events with dissimilar perceptions; in other instances numerous narrators contribute to the movement of a story, one at a time. Multiple points of views show the reader what the various characters are thinking and feeling or how they individually view events and other characters.

For many years, my eighth graders read Paul Zindel’s The Pigman, considered one of the first “adolescent literature” novels. The novel was written for adolescents, featuring adolescents, and written from an adolescent point of view. In the novel sophomores John and Lorraine befriend a lonely elderly neighbor, Angelo Pignati, and take advantage of his many kindnesses. I think what captivated both my male and female readers was the way alternating chapters were narrated by John and Lorraine, allowing readers to not only become familiar with each character but to perceive their differing perspectives on situations.

Some of my favorite novels feature multiple, diverse voices many times alternating narrators. Some are written by two authors, each writing one voice,; some are written in dual formats, such as free verse for one character and prose for the other. And some stories are told through a multiplicity of voices. And some present two timelines.

My more recently-read are reviewed below.

Nine Ten: A September 11th Story; Takedown; Anybody Here See Frenchie?; Forget Me Not; In Your Shoes; The Someday Suitcase; Consider the Octopus; Seven Clues to Home; The Magical Imperfect; Trowbridge Road; What is Goodbye?; Flight of the Puffin; The Crossover; Second Chance Summer; The Shape of Thunder; A Place at the Table; The Last Fifth Grade of Emerson Elementary; Two Naomis; Breakout; Harbor Me; Operation Frog Effect; Save Me a Seat; Runt; Becoming Muhammed Ali; Basketball or Something Like It; Unbound; Lily and Dunkin; Hidden Truths; Bronx Masquerade; Between the Lines; From Night Owl to Dogfish; How It Went Down; Farewell Cuba, Mi Isla; Redwood and Ponytail; Kaleidoscope Eyes; The Trial; Ringside; Flooded; Every Shiny Thing; Witness; Mixed Up; Seedfolks; With Their Eyes; Hidden; Out of the Dust; BenBee and the Teacher Griefer; Ben Y and the Ghost in the Machine; Jordan J and the Truth about Jordan J; Parkland Speaks; Paper Hearts; Virtually Me; Moonwalking; All We Have Left; Dig; Jump Ball; Falling Short; Torch; Kent State; Clap When You Land; October Mourning; The Wolves Are Waiting; Forward Me Back to You; The Pigman; Some Boys; Your Heart-My Sky; The Memory of Things; Same But Different; Loving vs Virginia; Eleanor and Park; The Lines We Cross

Stories Told through Alternating Narrators

A Place at the Table by Saadia Faruqi and Laura Shovan

“Elizabeth turns again to look at me, her face slightly shocked. I don’t think I’ve ever said anything much in class before. She gives me a thumbs up. Raising my hand in class, making friends with Elizabeth and Micah; I’m very different from the girl I was at the start of sixth grade.” (211)

“I have to talk to you. About what happened at the mall.… Sara is my friend. You shouldn’t have spoken to her like that. And I heard what you said to Ahsan yesterday…. There’s a difference between being mean and being racist, Mads.” (223-224)

Sixth grade is challenging. Sara had to leave her small Muslim school and enter a large middle school where the kids know each other and there are very few Muslim students. And to make matters worse, her mother runs the cooking club, teaching them to cook South Asian food from her native Pakistan.

The year becomes equally challenging for Elizabeth. She is the child of a British mother who has been depressed since her own mother’s death and a Jewish American father who travels all the time for his job. “Why can’t I have normal parents? A mom who remembers things like cookies for synagogue. A dad who’s home and can remind her.” (165) And her best friend Maddy becomes friends with Stephanie and begins spouting her parents’ racist remarks at Sara.

When Sara and Elizabeth become cooking partners and then friends, they both undergo change. Sara learns she doesn’t have to stay invisible, and Elizabeth learns to stand up for what she feels is right, especially for friends. “If we’re going to be real friends, not just cooking partners, that means we stick up for each other.” (149) Sara and Elizabeth may come from different cultures but they have much in common, such as mothers who are both studying to take their citizenship test. Children of immigrants in neighborhoods where the Christmas lights cover houses, they both feel different from those in their community, other than Micah, their Jewish half-Latino friend.

Through cooking and combining cultures for a cooking contest recipe, they discover friendship and that others, such as Maddy and Stephanie, are not always what they assumed.

Written in alternating chapters by two authors who mirror their characters, Sara and Elizabeth will help readers build conversations about friendships, prejudice, and following passions.

----------

“Elizabeth turns again to look at me, her face slightly shocked. I don’t think I’ve ever said anything much in class before. She gives me a thumbs up. Raising my hand in class, making friends with Elizabeth and Micah; I’m very different from the girl I was at the start of sixth grade.” (211)

“I have to talk to you. About what happened at the mall.… Sara is my friend. You shouldn’t have spoken to her like that. And I heard what you said to Ahsan yesterday…. There’s a difference between being mean and being racist, Mads.” (223-224)

Sixth grade is challenging. Sara had to leave her small Muslim school and enter a large middle school where the kids know each other and there are very few Muslim students. And to make matters worse, her mother runs the cooking club, teaching them to cook South Asian food from her native Pakistan.

The year becomes equally challenging for Elizabeth. She is the child of a British mother who has been depressed since her own mother’s death and a Jewish American father who travels all the time for his job. “Why can’t I have normal parents? A mom who remembers things like cookies for synagogue. A dad who’s home and can remind her.” (165) And her best friend Maddy becomes friends with Stephanie and begins spouting her parents’ racist remarks at Sara.

When Sara and Elizabeth become cooking partners and then friends, they both undergo change. Sara learns she doesn’t have to stay invisible, and Elizabeth learns to stand up for what she feels is right, especially for friends. “If we’re going to be real friends, not just cooking partners, that means we stick up for each other.” (149) Sara and Elizabeth may come from different cultures but they have much in common, such as mothers who are both studying to take their citizenship test. Children of immigrants in neighborhoods where the Christmas lights cover houses, they both feel different from those in their community, other than Micah, their Jewish half-Latino friend.

Through cooking and combining cultures for a cooking contest recipe, they discover friendship and that others, such as Maddy and Stephanie, are not always what they assumed.

Written in alternating chapters by two authors who mirror their characters, Sara and Elizabeth will help readers build conversations about friendships, prejudice, and following passions.

----------

All We Have Left by Wendy Mills

Before and After. But there also was a Then or That Day and an After.

All We Have Left was so compelling that I read from dawn to dusk and did not put the book down until I finished. The novel intertwines two stories, that of 18-year-old Travis and sixteen-year-old Alia who were in the Towers as they fell and the story of Travis’ sister, Jesse, who, fifteen years later, is part of a dysfunctional family whose lives are still overwhelmingly affected by That Day and Travis’ death.

Seventeen year old Jesse is not sure who she is, who she should be, who she should hate, and who she can love. Her life is overshadowed by 9/11, her mother’s mourning, and her father’s hate.

But both Alia in 2001, and Jesse in 2016, learn that “Faith and strength aren’t something that you wear like some sort of costume; they come from inside you” (p.329) as does love. And Jesse realizes that she has to work on “treasuring right here, right now, because that’s important.” As one character says but all the characters learn, “You can fill that void inside you with anger, or you can fill it with the love for the ones who remain beside you, with hope for the future.”

What I appreciated about this novel is that is shows yet another side of how 9/11 affected people, especially adolescents, those adolescents who populate American schools everywhere. I strongly feel that students should not only be learning about the events and effects of 9/11, but that, through novels, readers learn more about how events affect people and especially children their ages.

Before and After. But there also was a Then or That Day and an After.

All We Have Left was so compelling that I read from dawn to dusk and did not put the book down until I finished. The novel intertwines two stories, that of 18-year-old Travis and sixteen-year-old Alia who were in the Towers as they fell and the story of Travis’ sister, Jesse, who, fifteen years later, is part of a dysfunctional family whose lives are still overwhelmingly affected by That Day and Travis’ death.

Seventeen year old Jesse is not sure who she is, who she should be, who she should hate, and who she can love. Her life is overshadowed by 9/11, her mother’s mourning, and her father’s hate.

But both Alia in 2001, and Jesse in 2016, learn that “Faith and strength aren’t something that you wear like some sort of costume; they come from inside you” (p.329) as does love. And Jesse realizes that she has to work on “treasuring right here, right now, because that’s important.” As one character says but all the characters learn, “You can fill that void inside you with anger, or you can fill it with the love for the ones who remain beside you, with hope for the future.”

What I appreciated about this novel is that is shows yet another side of how 9/11 affected people, especially adolescents, those adolescents who populate American schools everywhere. I strongly feel that students should not only be learning about the events and effects of 9/11, but that, through novels, readers learn more about how events affect people and especially children their ages.

Becoming Muhammed Ali by James Patterson and Kwame Alexander

Becoming Muhammed Ali relates the story of boxer Cassius Clay from the time he began training as an amateur boxer at age 12 until he won the Chicago Golden Gloves on March 25, 1959—with glimpses forward to his 1960 Olympic gold medal and his transformation to Muhammad Ali.

The novel is creatively co-written by two authors in the voices of two narrator-characters: James Patterson writes as Cassius’ childhood best friend Lucius “Lucky” in prose and Kwame Alexander writes in verse, sometimes rhyming, most times not, as Cassius Clay. Dawud Anyabwile drew the wonderful illustrations.

Cassius Clay’s grandaddy always advised him, “Know who you are, Cassius. And whose you are. Know where you going and where you from.” (25) and he did. From Louisville, Kentucky, from Bird and Clay, and (in his own “I Am From” poem) from “slavery to freedom,…from the unfulfilled dreams of my father to the hallelujah hopes of my momma.” (28-29)

Readers learn WHY Cassius Cassius fought,

“for my name

for my life

for Papa Cash

and Momma Bird

for my grandaddy

and his grandaddy…

for America

for my chance

for my children

for their children

for a chance

at something better

at something way

greater.” (296-297)

As Lucky tells the reader, “He was loud. He was proud. He called himself the Greatest. Even when he wasn’t. Yet. But deep down, where it mattered, he could be very humble. It was another part of him that he didn’t let most people see.” (231) “He was also a true and loyal friend.” (305)

Throughout the novel, readers also learn boxing moves, information about famous boxers, such as Joe Louis and Rocky Marciano, and matches, and even more about the person who was Cassius Clay and became Muhammad Ali.

----------

Becoming Muhammed Ali relates the story of boxer Cassius Clay from the time he began training as an amateur boxer at age 12 until he won the Chicago Golden Gloves on March 25, 1959—with glimpses forward to his 1960 Olympic gold medal and his transformation to Muhammad Ali.

The novel is creatively co-written by two authors in the voices of two narrator-characters: James Patterson writes as Cassius’ childhood best friend Lucius “Lucky” in prose and Kwame Alexander writes in verse, sometimes rhyming, most times not, as Cassius Clay. Dawud Anyabwile drew the wonderful illustrations.

Cassius Clay’s grandaddy always advised him, “Know who you are, Cassius. And whose you are. Know where you going and where you from.” (25) and he did. From Louisville, Kentucky, from Bird and Clay, and (in his own “I Am From” poem) from “slavery to freedom,…from the unfulfilled dreams of my father to the hallelujah hopes of my momma.” (28-29)

Readers learn WHY Cassius Cassius fought,

“for my name

for my life

for Papa Cash

and Momma Bird

for my grandaddy

and his grandaddy…

for America

for my chance

for my children

for their children

for a chance

at something better

at something way

greater.” (296-297)

As Lucky tells the reader, “He was loud. He was proud. He called himself the Greatest. Even when he wasn’t. Yet. But deep down, where it mattered, he could be very humble. It was another part of him that he didn’t let most people see.” (231) “He was also a true and loyal friend.” (305)

Throughout the novel, readers also learn boxing moves, information about famous boxers, such as Joe Louis and Rocky Marciano, and matches, and even more about the person who was Cassius Clay and became Muhammad Ali.

----------

Clap When You Land (verse novel) by Elizabeth Acevedo

One plane crash. One father’s death. Two families’ loss.

“Papi boards the same flight every year.” (18) This year when her father leaves for his annual 3 months in his homeland, Yahaira knows the secret he has kept for 17 years. But she is unaware of who else knows. Not Camino, the other daughter who is practically Yahaira’s twin. Camino only knows she has a Papi who lives and works in New York City nine months a year to support her and the aunt who has raised her since her mother died.

When Papi’s plane crashes on its way from New York to the Dominican Republic, all passengers lose their lives and many families are left grieving. But none are more affected than the two daughters who loved their Papi, the two daughters whose mothers he had married.

Sixteen year old Yahaira lives in NYC, a high school chess champion until she discovered her father’s secret second marriage certificate and stopped speaking to him and stopped competing, and has a girlfriend who is an environmentalist and a deep sense of what’s right. “This girl felt about me/how I felt about her.” (77) Growing up in NYC, Yahaira was raised Dominican.

Sixteen year old Camino’s mother died quite suddenly when she was young, and she and her aunt, the community spiritual healer, are dependent on the money her father sends. Not wealthy by any means, they are the considered well-off in the barrio where Papi was raised; Camino goes to a private school and her father pays the local sex trafficker to leave her alone. And then the plane crash occurs.

Camino’s goal has always been to move to New York, live with her father, and study to become a doctor at Columbia University. Finding out about her father’s family in New York, she makes a plan with her share of the insurance money from the airlines. But Yahaira has her own plan—to go to her father’s Dominican burial despite the wishes of her mother, meet this sister, and explore her culture.

When they all show up, readers see just how powerfully a family can form.

An article about Flight AA587: https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2011/11/remembering-americas-second-deadliest-plane-crash/248313/

----------

One plane crash. One father’s death. Two families’ loss.

“Papi boards the same flight every year.” (18) This year when her father leaves for his annual 3 months in his homeland, Yahaira knows the secret he has kept for 17 years. But she is unaware of who else knows. Not Camino, the other daughter who is practically Yahaira’s twin. Camino only knows she has a Papi who lives and works in New York City nine months a year to support her and the aunt who has raised her since her mother died.

When Papi’s plane crashes on its way from New York to the Dominican Republic, all passengers lose their lives and many families are left grieving. But none are more affected than the two daughters who loved their Papi, the two daughters whose mothers he had married.

Sixteen year old Yahaira lives in NYC, a high school chess champion until she discovered her father’s secret second marriage certificate and stopped speaking to him and stopped competing, and has a girlfriend who is an environmentalist and a deep sense of what’s right. “This girl felt about me/how I felt about her.” (77) Growing up in NYC, Yahaira was raised Dominican.

Sixteen year old Camino’s mother died quite suddenly when she was young, and she and her aunt, the community spiritual healer, are dependent on the money her father sends. Not wealthy by any means, they are the considered well-off in the barrio where Papi was raised; Camino goes to a private school and her father pays the local sex trafficker to leave her alone. And then the plane crash occurs.

Camino’s goal has always been to move to New York, live with her father, and study to become a doctor at Columbia University. Finding out about her father’s family in New York, she makes a plan with her share of the insurance money from the airlines. But Yahaira has her own plan—to go to her father’s Dominican burial despite the wishes of her mother, meet this sister, and explore her culture.

When they all show up, readers see just how powerfully a family can form.

An article about Flight AA587: https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2011/11/remembering-americas-second-deadliest-plane-crash/248313/

----------

Consider the Octopus by Nora Raleigh Baskin and Gae Polisner

“Consider the octopus, dude, duh,” I say out loud to myself because sometimes it helps to talk to someone. “That part is the important part. The octopus.” (88)

And the pink octopus avatar starts the chain of events which lead 12-year-old Sydney Miller (not marine biologist Dr. Sydney Miller of the Monterey Bay Aquarium) and her goldfish Rachel Carson to Oceana II, a ship researching the Great PGP.

When seventh-grader Jeremy JB Barnes, under the custody of his recently-divorced mother, chief scientist of the Oceana II, finds himself accompanying her on her mission “to sweep and vacuum up approximately eighty-eight thousand tons of garbage” called the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, he was less than enthusiastic. “I like the ocean plenty from the beach.”

Until the high school SEAmester students arrive, he is the only adolescent on board. But tasked with the job of inviting well-known scientists to the join them, JB inadvertently sends the invitation to the wrong Sydney Miller who jumps at the chance, looking for something to do this summer now that her best and only friend has moved away. Sydney and her grandmother agree, “It’s synchronicity” (91), the simultaneous occurrence of events which appear significantly related but have no discernible causal connection. “What psychologist Carl Jung called ‘meaningful coincidences’…” (228) However, “These signs we see all the time, the universe, these coincidences that we give meaning? They only work if we want them to…” (12)

And Sydney and Jeremy want these signs to work. Hiding Sydney on the ship, sometimes in plain sight with the help of two of the SEAmster girls, Sydney and JB hatch a plan to bring about the publicity the mission needs to retains its grant. “Maybe we’re here because we’re supposed to be here. Maybe the two of us are supposed to do something really important.” (144)

When you put two of my favorite authors together, what do readers get? A fun, important adventure with engaging characters who present two voices, representing two perspectives, and who show that, according to news reporter Damian Jacks, “Mark my words: kids and our youth. That’s who’s going to really help change things..… Kids, not adults, are the future of our planet.” (171)

And there is a lot of science and information about the polluting of the oceans. “It’s amazing how many people still don’t know how much waste—garbage,” she corrects herself, “is floating in the middle of the Pacific.” (226)

Readers learn about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and its importance to our environment. Besides the garbage that is killing sea life—birds and fish, this affects all of us.

“Because every drop of water we have, all of it, circles around, evaporates into the sky, and comes back down as rain, or mist, or snow. It sinks into the ground and fills rivers, ponds, lakes, reservoirs, and the well in my backyard.

Water I shower with. Cook with.

And drink.

No new water is ever made.

This is all we’ve got.” (167)

An important read, this novel could be included in an environmental impacts study in ELA or science classes, leading to more research on the topic.

“Consider the octopus, dude, duh,” I say out loud to myself because sometimes it helps to talk to someone. “That part is the important part. The octopus.” (88)

And the pink octopus avatar starts the chain of events which lead 12-year-old Sydney Miller (not marine biologist Dr. Sydney Miller of the Monterey Bay Aquarium) and her goldfish Rachel Carson to Oceana II, a ship researching the Great PGP.

When seventh-grader Jeremy JB Barnes, under the custody of his recently-divorced mother, chief scientist of the Oceana II, finds himself accompanying her on her mission “to sweep and vacuum up approximately eighty-eight thousand tons of garbage” called the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, he was less than enthusiastic. “I like the ocean plenty from the beach.”

Until the high school SEAmester students arrive, he is the only adolescent on board. But tasked with the job of inviting well-known scientists to the join them, JB inadvertently sends the invitation to the wrong Sydney Miller who jumps at the chance, looking for something to do this summer now that her best and only friend has moved away. Sydney and her grandmother agree, “It’s synchronicity” (91), the simultaneous occurrence of events which appear significantly related but have no discernible causal connection. “What psychologist Carl Jung called ‘meaningful coincidences’…” (228) However, “These signs we see all the time, the universe, these coincidences that we give meaning? They only work if we want them to…” (12)

And Sydney and Jeremy want these signs to work. Hiding Sydney on the ship, sometimes in plain sight with the help of two of the SEAmster girls, Sydney and JB hatch a plan to bring about the publicity the mission needs to retains its grant. “Maybe we’re here because we’re supposed to be here. Maybe the two of us are supposed to do something really important.” (144)

When you put two of my favorite authors together, what do readers get? A fun, important adventure with engaging characters who present two voices, representing two perspectives, and who show that, according to news reporter Damian Jacks, “Mark my words: kids and our youth. That’s who’s going to really help change things..… Kids, not adults, are the future of our planet.” (171)

And there is a lot of science and information about the polluting of the oceans. “It’s amazing how many people still don’t know how much waste—garbage,” she corrects herself, “is floating in the middle of the Pacific.” (226)

Readers learn about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and its importance to our environment. Besides the garbage that is killing sea life—birds and fish, this affects all of us.

“Because every drop of water we have, all of it, circles around, evaporates into the sky, and comes back down as rain, or mist, or snow. It sinks into the ground and fills rivers, ponds, lakes, reservoirs, and the well in my backyard.

Water I shower with. Cook with.

And drink.

No new water is ever made.

This is all we’ve got.” (167)

An important read, this novel could be included in an environmental impacts study in ELA or science classes, leading to more research on the topic.

Every Shiny Thing (prose-verse) by Cordelia Jensen and Laurie Morrison

In Cordelia Jensen and Laurie Morrison’s new MG novel Every Shiny Thing readers follow the journey of two new friends from different types of lives as they discover themselves and how they can navigate their lives.

Lauren is a wealthy teen who goes to a Quaker school. She is very close to her brother Ryan but when he is sent to a boarding school for teens on the autism spectrum, Lauren is sure that he isn’t happy, that the school is not meeting his needs, and that her parents sent him away. She then realizes that all teens who need it can’t afford the help Ryan is getting and she designs a scheme to raise money, selling the “shiny things” that she feels her affluent family and friends don’t really need. Her scheme spirals out of control as she begins stealing items from stores, family, and friends, selling them on line, and the thrill of stealing takes over. She even involves her new friend Sierra.

Sierra’s father, a drug addict, is in jail; her mother, an alcoholic, who Sierra has cared for for years in a life of poverty, is also in jail. What she wants is her family; what she needs is a stable loving family—and a friend, but not a friend who gets her involved with her own addiction.

Sierra moves in next door to Lauren with her foster parents Carl and Anne, an interracial Quaker couple who are surviving the trauma of losing their own child. She pushes them away, anxious to get back to her old life, but “In the end, he [Carl] had me find the proof/ before the statement./ A new way to think.” (p 235) Sierra and Lauren’s friendship guides them in finding a new way of thinking. Sierra realizes she can love her mother but she can’t help her, and she can let Carl and Anne help her. “I know I can’t be your mom, Sierra,/ but I can be your Anne.” (p. 333) Lauren realizes that she can stop worrying about Ryan who is happy in his new environment and she can’t save the world, but “I do know this: I’m not going to forget about Hailey or zone out when I walk past someone asking for money on the street. I won’t. Because someday, maybe, I’ll be able to do something more.” (p. 353)

Lauren’s and Sierra’s narrations are written by each of the authors in their own unique style: Lauren’s narratives in prose and Sierra’s in free verse, styles which fit their lives and personalities. Their lives are populated by culturally diverse friends and their families as they traverse the Philadelphia I know so well.

----------

In Cordelia Jensen and Laurie Morrison’s new MG novel Every Shiny Thing readers follow the journey of two new friends from different types of lives as they discover themselves and how they can navigate their lives.

Lauren is a wealthy teen who goes to a Quaker school. She is very close to her brother Ryan but when he is sent to a boarding school for teens on the autism spectrum, Lauren is sure that he isn’t happy, that the school is not meeting his needs, and that her parents sent him away. She then realizes that all teens who need it can’t afford the help Ryan is getting and she designs a scheme to raise money, selling the “shiny things” that she feels her affluent family and friends don’t really need. Her scheme spirals out of control as she begins stealing items from stores, family, and friends, selling them on line, and the thrill of stealing takes over. She even involves her new friend Sierra.

Sierra’s father, a drug addict, is in jail; her mother, an alcoholic, who Sierra has cared for for years in a life of poverty, is also in jail. What she wants is her family; what she needs is a stable loving family—and a friend, but not a friend who gets her involved with her own addiction.

Sierra moves in next door to Lauren with her foster parents Carl and Anne, an interracial Quaker couple who are surviving the trauma of losing their own child. She pushes them away, anxious to get back to her old life, but “In the end, he [Carl] had me find the proof/ before the statement./ A new way to think.” (p 235) Sierra and Lauren’s friendship guides them in finding a new way of thinking. Sierra realizes she can love her mother but she can’t help her, and she can let Carl and Anne help her. “I know I can’t be your mom, Sierra,/ but I can be your Anne.” (p. 333) Lauren realizes that she can stop worrying about Ryan who is happy in his new environment and she can’t save the world, but “I do know this: I’m not going to forget about Hailey or zone out when I walk past someone asking for money on the street. I won’t. Because someday, maybe, I’ll be able to do something more.” (p. 353)

Lauren’s and Sierra’s narrations are written by each of the authors in their own unique style: Lauren’s narratives in prose and Sierra’s in free verse, styles which fit their lives and personalities. Their lives are populated by culturally diverse friends and their families as they traverse the Philadelphia I know so well.

----------

Falling Short by Ernesto Cisneros

“I’m not sure everyone has a best friend like I do. No, not the average “bestie” you pretty much only see and talk to at school. I’m talking best friends who know you inside and out. Friends you feel comfortable enough to cry or change in front of, friends so close that they feel more like a brother or sister.

That’s what I’ve got in Isaac.

And I would do anything for him. Just like he’d do for me.” (180)

Sixth graders Isaac and Marco are best friends not only because they are very, very good friends but because they each want the best for the other. Isaac is athletically gifted and a star of the basketball team but has problems with school work; Marco is academically gifted but wants to become an athlete to win the approval of his father who left home for a new girlfriend and her son. Isaac’s father also left home but because his drinking problem has gotten the best of him. “Drinking had pretty much become more important than either Ama or me.” (92)

When the very short Marco learns of 5’3” NBA player Muggsy Bogues, he decides to try out for the school basketball team and, with the determination he applies to everything, studies YouTube videos and practices nonstop. Isaac becomes his coach and even figures out how he can change his plays to help Marco be successful. “That’s probably the one thing that separates [Isaac] from every other kid I’ve ever met. He never judges me. Never makes me feel stupid.” (154) And when Isaac helps Marco with his schoolwork (in a strange turn of events), he learns that he is smarter than he thought.

Told in alternating narratives by Isaac and Marco, this is a story of true friendship, broken families, bullying, sports (I learned a lot of basketball terms!), teamwork and collaboration, featuring Latinx and Jewish characters. It is story of what is takes to not fall short.

----------

“I’m not sure everyone has a best friend like I do. No, not the average “bestie” you pretty much only see and talk to at school. I’m talking best friends who know you inside and out. Friends you feel comfortable enough to cry or change in front of, friends so close that they feel more like a brother or sister.

That’s what I’ve got in Isaac.

And I would do anything for him. Just like he’d do for me.” (180)

Sixth graders Isaac and Marco are best friends not only because they are very, very good friends but because they each want the best for the other. Isaac is athletically gifted and a star of the basketball team but has problems with school work; Marco is academically gifted but wants to become an athlete to win the approval of his father who left home for a new girlfriend and her son. Isaac’s father also left home but because his drinking problem has gotten the best of him. “Drinking had pretty much become more important than either Ama or me.” (92)

When the very short Marco learns of 5’3” NBA player Muggsy Bogues, he decides to try out for the school basketball team and, with the determination he applies to everything, studies YouTube videos and practices nonstop. Isaac becomes his coach and even figures out how he can change his plays to help Marco be successful. “That’s probably the one thing that separates [Isaac] from every other kid I’ve ever met. He never judges me. Never makes me feel stupid.” (154) And when Isaac helps Marco with his schoolwork (in a strange turn of events), he learns that he is smarter than he thought.

Told in alternating narratives by Isaac and Marco, this is a story of true friendship, broken families, bullying, sports (I learned a lot of basketball terms!), teamwork and collaboration, featuring Latinx and Jewish characters. It is story of what is takes to not fall short.

----------

Farewell Cuba, Mi Isla by Alexandra Diaz

“Look outside your window, children,” Mami said as they took their seats. “You may never see your country again.” (ARC, 36)

Victoria had a wonderful life in Cuba where she lived with her mother, father, and younger sister and brother. Also in the same duplex lived her cousin Jackie, her aunt, her uncle, and her baby cousin/godson. Even though they were very different and attended different schools in Havana, 12-year-old Victoria and Jackie were best friends, and they both spent time at their Papalfonso and Mamlara’s finca where Victoria rode her horse and swam with her cousin, a ranch that Victoria would inherit.

October 1960: With Fidel Castro in power and protestors arrested, news restricted, and professionals prohibited from leaving the country, Victoria’s family makes the decision to go to Miami, expecting their exile to “only last a few weeks, until the U.S. presidential election.” (14)

Alternating chapters focus on Victoria and Jackie and permit readers to learn what is happening in Cuba and about the Cuban community in Miami. Here Victoria lives in poverty (her father’s engineering degree of no use as he labors for minimum wage), and she tries to take charge of feeding her family. When Jackie arrives in Miami through the Peter Pan Project (reminiscent of the Holocaust Kindertransport), readers see how being apart from her immediate family affects her and her relationship with Victoria.

I often have read and reviewed novels (and memoirs) by Margarita Engle and noted that I learned quite a lot of Cuban history, a history missing from my education. Diaz’s novel, inspired by the experiences of her mother and family who came to the

United States from Cuba in 1960, spans October 1960 to June 1961 and teaches readers even more about Castro and his effect on Cuba and the Cuban citizens and the role the U.S. government played. This novel should be included in every American history course. This is also a story of prejudice, as experienced by Katya, Victoria’s Russian school friend, and of resilience and family. The Author’s Note further expands on the historical facts and includes a glossary of Cuban terms.

“Look outside your window, children,” Mami said as they took their seats. “You may never see your country again.” (ARC, 36)

Victoria had a wonderful life in Cuba where she lived with her mother, father, and younger sister and brother. Also in the same duplex lived her cousin Jackie, her aunt, her uncle, and her baby cousin/godson. Even though they were very different and attended different schools in Havana, 12-year-old Victoria and Jackie were best friends, and they both spent time at their Papalfonso and Mamlara’s finca where Victoria rode her horse and swam with her cousin, a ranch that Victoria would inherit.

October 1960: With Fidel Castro in power and protestors arrested, news restricted, and professionals prohibited from leaving the country, Victoria’s family makes the decision to go to Miami, expecting their exile to “only last a few weeks, until the U.S. presidential election.” (14)

Alternating chapters focus on Victoria and Jackie and permit readers to learn what is happening in Cuba and about the Cuban community in Miami. Here Victoria lives in poverty (her father’s engineering degree of no use as he labors for minimum wage), and she tries to take charge of feeding her family. When Jackie arrives in Miami through the Peter Pan Project (reminiscent of the Holocaust Kindertransport), readers see how being apart from her immediate family affects her and her relationship with Victoria.

I often have read and reviewed novels (and memoirs) by Margarita Engle and noted that I learned quite a lot of Cuban history, a history missing from my education. Diaz’s novel, inspired by the experiences of her mother and family who came to the

United States from Cuba in 1960, spans October 1960 to June 1961 and teaches readers even more about Castro and his effect on Cuba and the Cuban citizens and the role the U.S. government played. This novel should be included in every American history course. This is also a story of prejudice, as experienced by Katya, Victoria’s Russian school friend, and of resilience and family. The Author’s Note further expands on the historical facts and includes a glossary of Cuban terms.

Forget Me Not (prose-verse) by Ellie Terry

Seventh grade is hard to navigate, even when you are not different.

Jinsong is the president of student body, and even though he has faced prejudice in his past, he is now one of the popular seventh graders. When Calliope June moves in next door, with her weird clothing and tics, he immediately likes her. But does he like her enough to risk his standing with his "friends," who are bullying Callie and some of whom have turned on him in the past?

Callie has moved ten times during her life—every time her mother finds and breaks up with a new boyfriend. Diagnosed with Tourette syndrome, it is hard enough to fit in and make friends, especially since her doctor told her it would be better not to tell anyone.

So Callie dresses to draw attention to her clothes and tries to hide her Tourette's (which only backfires) as she desperately tries to make friends—until she meets Jinsong and Ms. Baumgartner, the school counselor. Callie moves for an 11th time, leaving a legacy of tolerance and acceptance, at least between Beatriz and Jinsong—and ready to share her whole self with her new friends. "Because wouldn't/ talking/ about something/ make it better understood?"

The reader learns about Callie, her past, her present, her future dreams, through her free-verse chapters and about Jinsong through his short prose. This is a perfect novel for reluctant readers as it is very short but leaves much to discuss (and contains both a male and female main character). Author Ellie Askeroth Terry's shares her own experience in this debut novel.

----------

Seventh grade is hard to navigate, even when you are not different.

Jinsong is the president of student body, and even though he has faced prejudice in his past, he is now one of the popular seventh graders. When Calliope June moves in next door, with her weird clothing and tics, he immediately likes her. But does he like her enough to risk his standing with his "friends," who are bullying Callie and some of whom have turned on him in the past?

Callie has moved ten times during her life—every time her mother finds and breaks up with a new boyfriend. Diagnosed with Tourette syndrome, it is hard enough to fit in and make friends, especially since her doctor told her it would be better not to tell anyone.

So Callie dresses to draw attention to her clothes and tries to hide her Tourette's (which only backfires) as she desperately tries to make friends—until she meets Jinsong and Ms. Baumgartner, the school counselor. Callie moves for an 11th time, leaving a legacy of tolerance and acceptance, at least between Beatriz and Jinsong—and ready to share her whole self with her new friends. "Because wouldn't/ talking/ about something/ make it better understood?"

The reader learns about Callie, her past, her present, her future dreams, through her free-verse chapters and about Jinsong through his short prose. This is a perfect novel for reluctant readers as it is very short but leaves much to discuss (and contains both a male and female main character). Author Ellie Askeroth Terry's shares her own experience in this debut novel.

----------

Forward Me Back to You by Mitali Perkins

When 16-year-old Katina is assaulted in the stairwell by the popular star basketball player, her jujitsu skills let her defend herself. But when she reports the attack, it is she who is made so uncomfortable she has to leave school. Her confidence shattered, she wonders if she will ever be able to trust men again.

Robin was born in Kolkata, abandoned by his mother, and adopted by loving, wealthy, supportive American parents at age three, but he has never stopped thinking about his first mother and his life seems to have no direction.

When Kat is sent to Boston to be homeschooled by a family friend’s aunt, Grandma Vee, she becomes a part of a teen church group. When Pastor Gregory takes Robin, Katina, and Gracie to Kolkata to work with female human trafficking survivors, with the help of her new support system and some of the young survivors themselves, Katina learns to trust again; Robin, now Ravi, finds purpose in his life; and Gracie, who was the major support system for both of them, finally gets Ravi to realize his love for her.

Told through very short chapters that alternate between Kat and Robin and simply written, Mitali Perkins’ novel is a valuable read that is accessible to, and appropriate for, all adolescent readers.

----------

When 16-year-old Katina is assaulted in the stairwell by the popular star basketball player, her jujitsu skills let her defend herself. But when she reports the attack, it is she who is made so uncomfortable she has to leave school. Her confidence shattered, she wonders if she will ever be able to trust men again.

Robin was born in Kolkata, abandoned by his mother, and adopted by loving, wealthy, supportive American parents at age three, but he has never stopped thinking about his first mother and his life seems to have no direction.

When Kat is sent to Boston to be homeschooled by a family friend’s aunt, Grandma Vee, she becomes a part of a teen church group. When Pastor Gregory takes Robin, Katina, and Gracie to Kolkata to work with female human trafficking survivors, with the help of her new support system and some of the young survivors themselves, Katina learns to trust again; Robin, now Ravi, finds purpose in his life; and Gracie, who was the major support system for both of them, finally gets Ravi to realize his love for her.

Told through very short chapters that alternate between Kat and Robin and simply written, Mitali Perkins’ novel is a valuable read that is accessible to, and appropriate for, all adolescent readers.

----------

Hidden (verse) by Helen Frost

Confusing feelings, complex relationships, and speculative blame develop from a simple plot in Hidden—even though both girls were there.

When she was eight, a man ran from a botched burglary and stole Wren’s mother’s car. Wren was in the back, hidden. West didn’t know she was there until he hid the car in his garage and heard on the news that a child who was in a stolen car was missing. West’s wife and daughter, although threatened and hit by West, tried to find her, and eight-year old Darra leaves food in the garage just in case the girl is there. Wren escapes, and West is caught and sentenced to a jail term, and Darra grows up with ambivalent feelings for the girl who took her “Dad” away.

Six years later the two girls meet at camp. They aren’t sure how they feel about each other, but they agree to avoid each other and not discuss the incident. Until one day they are placed together for a life-saving class event and finally realize that they are the only ones that can discuss the past, and they begin to listen to each other’s side of the story “and put the pieces into place” (124). Darra reflects, “Does she think you can’t love a dad who yells at you and even hits you?”(120). When Wren reveals that she wasn’t the one who turned West in, Darra thinks, “Everything is turning upside down.” And reassures Wren “None of what happened was your fault” (124). Together, they become “stronger than we knew.” (138)

Hidden is written in different styles of free verse. Wren recount her past and present stories in the more traditional style of short lines and meaningful line breaks in combination with meaning word and line spacing. Darra’s narration is crafted in a unique style of long lines and shorter lines, the words at the end of each long line, read vertically, tell Darra’s past memories of her father and explain her love for him. I am glad I happened to read the author’s “Notes on Form” at the end of the story that explained the format or I might have missed the effectiveness of this creative format, although the reader could return to the text for the message.

----------

Confusing feelings, complex relationships, and speculative blame develop from a simple plot in Hidden—even though both girls were there.

When she was eight, a man ran from a botched burglary and stole Wren’s mother’s car. Wren was in the back, hidden. West didn’t know she was there until he hid the car in his garage and heard on the news that a child who was in a stolen car was missing. West’s wife and daughter, although threatened and hit by West, tried to find her, and eight-year old Darra leaves food in the garage just in case the girl is there. Wren escapes, and West is caught and sentenced to a jail term, and Darra grows up with ambivalent feelings for the girl who took her “Dad” away.

Six years later the two girls meet at camp. They aren’t sure how they feel about each other, but they agree to avoid each other and not discuss the incident. Until one day they are placed together for a life-saving class event and finally realize that they are the only ones that can discuss the past, and they begin to listen to each other’s side of the story “and put the pieces into place” (124). Darra reflects, “Does she think you can’t love a dad who yells at you and even hits you?”(120). When Wren reveals that she wasn’t the one who turned West in, Darra thinks, “Everything is turning upside down.” And reassures Wren “None of what happened was your fault” (124). Together, they become “stronger than we knew.” (138)

Hidden is written in different styles of free verse. Wren recount her past and present stories in the more traditional style of short lines and meaningful line breaks in combination with meaning word and line spacing. Darra’s narration is crafted in a unique style of long lines and shorter lines, the words at the end of each long line, read vertically, tell Darra’s past memories of her father and explain her love for him. I am glad I happened to read the author’s “Notes on Form” at the end of the story that explained the format or I might have missed the effectiveness of this creative format, although the reader could return to the text for the message.

----------

Hidden Truths by Elly Swartz

“You may not get to choose what sport you play or when you get to play it, but you get to choose who you are. And in the end, that’s what matters most.” (ARC, 194)

When Dani makes the all-boy baseball team, she is sure she has reached her goal. But when she goes on a camping trip with her best friend Eric and the camper explodes, trapping her inside, events seem to be keeping her from achieving her dream. Dani sustains injuries that, no matter how determined she is, will keep her from pitching this year.

And Eric, even though he went into the burning camper and rescued Dani, is afraid that, characteristically forgetful as he is, he left on the stove burner the night before and caused the fire. When he tells Dani, she can’t forgive him and allows her new friend, the popular Meadow, to call him a loser in front of the other kids in the school. Since she always has had his back, Eric is shocked, especially when they find out that he was not responsible for the incident and the bullying continues.

Eric finds out that the actual cause of the fire was a defective remote-control toy, and with his new crush Rachel and the help of a podcaster, takes the necessary steps to ensure the public is aware and that the manufacturer is stopped from producing the toy and made to recall those on the market. Eric has turned his ADD and ability to see things from different angles into his superpower.

Meanwhile Dani is not sure she likes the person she is becoming, especially when she finds out that her new friend has been telling lies.

My brain spins. Meadow’s not the person I thought she was. She’s the person Eric knew she was.

My eyes sting.

I miss my old life.

Tears hit my lap.

I miss me. (ARC, 206)

Told in alternating narratives by Dani and Eric, HIDDEN TRUTHS is a story of having a dream and changing that dream without changing yourself. It is a story of loss and what constitutes friendship and standing up to make a difference. Dani and Eric’s story can teach preteen readers many things about themselves, how to treat their peers, how to be part of a team, and how to see the person behind the person. It is a story about baseball, superheroes, and doughnuts—of love, forgiveness, and identity. It is a story that will resonate with readers and provide a map for those who are navigating the hidden truths of middle school.

Elly Swartz’s new novel can be grouped with a variety of other novels for Book Club Reading:

“You may not get to choose what sport you play or when you get to play it, but you get to choose who you are. And in the end, that’s what matters most.” (ARC, 194)

When Dani makes the all-boy baseball team, she is sure she has reached her goal. But when she goes on a camping trip with her best friend Eric and the camper explodes, trapping her inside, events seem to be keeping her from achieving her dream. Dani sustains injuries that, no matter how determined she is, will keep her from pitching this year.

And Eric, even though he went into the burning camper and rescued Dani, is afraid that, characteristically forgetful as he is, he left on the stove burner the night before and caused the fire. When he tells Dani, she can’t forgive him and allows her new friend, the popular Meadow, to call him a loser in front of the other kids in the school. Since she always has had his back, Eric is shocked, especially when they find out that he was not responsible for the incident and the bullying continues.

Eric finds out that the actual cause of the fire was a defective remote-control toy, and with his new crush Rachel and the help of a podcaster, takes the necessary steps to ensure the public is aware and that the manufacturer is stopped from producing the toy and made to recall those on the market. Eric has turned his ADD and ability to see things from different angles into his superpower.

Meanwhile Dani is not sure she likes the person she is becoming, especially when she finds out that her new friend has been telling lies.

My brain spins. Meadow’s not the person I thought she was. She’s the person Eric knew she was.

My eyes sting.

I miss my old life.

Tears hit my lap.

I miss me. (ARC, 206)

Told in alternating narratives by Dani and Eric, HIDDEN TRUTHS is a story of having a dream and changing that dream without changing yourself. It is a story of loss and what constitutes friendship and standing up to make a difference. Dani and Eric’s story can teach preteen readers many things about themselves, how to treat their peers, how to be part of a team, and how to see the person behind the person. It is a story about baseball, superheroes, and doughnuts—of love, forgiveness, and identity. It is a story that will resonate with readers and provide a map for those who are navigating the hidden truths of middle school.

Elly Swartz’s new novel can be grouped with a variety of other novels for Book Club Reading:

- Other stories told through Multiple Voices & Perspectives, https://www.literacywithlesley.com/multiple-voices--multiple-perspectives.html

- Other novels about Identity and Self-Discovery, https://www.literacywithlesley.com/identity--self-discovery.html

- Other “Books to Begin Conversations about Bullying,” https://www.literacywithlesley.com/bullying.html

- And to group Eric with other Justice & Change Seekers, https://www.literacywithlesley.com/justice--change-seekers.html

Loving vs. Virginia (verse) by Patricia Hruby Powell

Loving vs Virgina is the story behind the unanimous landmark decision of June 1967. Told in free verse through alternating narrations by Richard and Mildred, the story begins in Fall 1952 when 13-year old Mildred notices that her desk in the colored school is “ sad excuse for a desk” and her reader “reeks of grime and mildew and has been in the hands of many boys,” but she also relates also the closeness of family and friends in her summer vacation essay. This closeness is also expressed in the family’s Saturday dinner where “folks drop by,” one of them being the boy who catches Mildred’s ball during the kickball game and “Because of him I don’t get home.” That boy is her neighbor, nineteen-year-old Richard Loving, and that phrase becomes truer than Mildred could have guessed.

On June 2, 1958, Richard who is white and Mildred marry in Washington, D.C., and on July 11, 1958 they are arrested at her parents’ house in Virginia. The couple spends the next ten years living in D.C., sneaking into Virginia, and finally contacting the American Civil Liberties Union who brings their case through the courts to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The documentary novel brings the story behind the case alive, interspersed with quotes, news headlines and news reports, maps, timelines, and information on the various court cases, and the players involved, as the case made its way to the Supreme Court. Students can learn history from textbooks, from lectures, or more effectively and affectively, through the stories of the people involved. Novels are where readers learn empathy, vicariously living the lives of others.

----------

Loving vs Virgina is the story behind the unanimous landmark decision of June 1967. Told in free verse through alternating narrations by Richard and Mildred, the story begins in Fall 1952 when 13-year old Mildred notices that her desk in the colored school is “ sad excuse for a desk” and her reader “reeks of grime and mildew and has been in the hands of many boys,” but she also relates also the closeness of family and friends in her summer vacation essay. This closeness is also expressed in the family’s Saturday dinner where “folks drop by,” one of them being the boy who catches Mildred’s ball during the kickball game and “Because of him I don’t get home.” That boy is her neighbor, nineteen-year-old Richard Loving, and that phrase becomes truer than Mildred could have guessed.

On June 2, 1958, Richard who is white and Mildred marry in Washington, D.C., and on July 11, 1958 they are arrested at her parents’ house in Virginia. The couple spends the next ten years living in D.C., sneaking into Virginia, and finally contacting the American Civil Liberties Union who brings their case through the courts to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The documentary novel brings the story behind the case alive, interspersed with quotes, news headlines and news reports, maps, timelines, and information on the various court cases, and the players involved, as the case made its way to the Supreme Court. Students can learn history from textbooks, from lectures, or more effectively and affectively, through the stories of the people involved. Novels are where readers learn empathy, vicariously living the lives of others.

----------

Mixed Up by Gordon Korman

“Some things that happen are so big you’re never the same afterward.” (ARC 39)

Seventh grader Reef Moody is grieving the death of his mother a year ago. He has set himself off from his friends, especially Portia, the girl he likes. He is convinced that he contracted Covid from Portia at her party—a party he begged his mother to let him attend—and passed it to his mother who died a few weeks later, and he is riddled with guilt. He was taken in by his mother’s best friend, but her teen children are not happy with the situation, especially Declan who bullies Reef continually and even gets him into trouble with the school principal.

And strangely, Reef’s memories of his mother are growing dim; he can hardly remember her face and he doesn’t know why. But he does have vivid memories from a life that he knows is not his, a life with a yard and a garden and a rabbit named Jaws. And a few times he has executed karate moves.

Meanwhile, on the other side of town lives Theo Metzinger, a seventh grader who takes karate and grows vegetable and fights with his nemesis, a rabbit named Jaws. Theo is much of a loner to the disappointment of his father, who, as an adolescent, “ruled the school.” And lately Theo is having memories of a lady and feeling an unbearable sadness. When Theo, at his school, begins seeing a different school—different tiles, different walls, a different walkway, and a cupola, he begins investigating and locates Delgado Middle School on the other side of town where he meets Portia and eventually Reef. “At last [Theo] begins, ‘There are things I remember that I know for a fact never happened to me.’ ‘Me too!’ [Reef] jumps in breathlessly.” (ARC 94)

Reef is not happy to meet Theo who he feels is stealing his life, at least his past. “It hits me: If Theo has access to my memories. How can he remember what I can’t. The answer is so obvious: He’s not sharing my memories; he’s stealing them.” (ARC 97-98) But as the two boys lose more and more memories and have to rely on each other more and more, they realize they need to solve the mystery. Theo realizes that Reef has a lot to lose—his life with his mother. Discovering that they were born on the same day in the same hospital, they research the possible cause of this strange phenomenon and plan a dangerous experiment to reverse it, aided by, strangely enough, Declan.

Told in alternating narratives, this is a story of friendship, family, and the importance of memories. “Memory: the mental process of registering, storing, and retrieving information.” (ARC 102), but so much more.

----------

“Some things that happen are so big you’re never the same afterward.” (ARC 39)

Seventh grader Reef Moody is grieving the death of his mother a year ago. He has set himself off from his friends, especially Portia, the girl he likes. He is convinced that he contracted Covid from Portia at her party—a party he begged his mother to let him attend—and passed it to his mother who died a few weeks later, and he is riddled with guilt. He was taken in by his mother’s best friend, but her teen children are not happy with the situation, especially Declan who bullies Reef continually and even gets him into trouble with the school principal.

And strangely, Reef’s memories of his mother are growing dim; he can hardly remember her face and he doesn’t know why. But he does have vivid memories from a life that he knows is not his, a life with a yard and a garden and a rabbit named Jaws. And a few times he has executed karate moves.

Meanwhile, on the other side of town lives Theo Metzinger, a seventh grader who takes karate and grows vegetable and fights with his nemesis, a rabbit named Jaws. Theo is much of a loner to the disappointment of his father, who, as an adolescent, “ruled the school.” And lately Theo is having memories of a lady and feeling an unbearable sadness. When Theo, at his school, begins seeing a different school—different tiles, different walls, a different walkway, and a cupola, he begins investigating and locates Delgado Middle School on the other side of town where he meets Portia and eventually Reef. “At last [Theo] begins, ‘There are things I remember that I know for a fact never happened to me.’ ‘Me too!’ [Reef] jumps in breathlessly.” (ARC 94)

Reef is not happy to meet Theo who he feels is stealing his life, at least his past. “It hits me: If Theo has access to my memories. How can he remember what I can’t. The answer is so obvious: He’s not sharing my memories; he’s stealing them.” (ARC 97-98) But as the two boys lose more and more memories and have to rely on each other more and more, they realize they need to solve the mystery. Theo realizes that Reef has a lot to lose—his life with his mother. Discovering that they were born on the same day in the same hospital, they research the possible cause of this strange phenomenon and plan a dangerous experiment to reverse it, aided by, strangely enough, Declan.

Told in alternating narratives, this is a story of friendship, family, and the importance of memories. “Memory: the mental process of registering, storing, and retrieving information.” (ARC 102), but so much more.

----------

Moonwalking by Lyn Miller- Lachmann and Zetta Elliott

Solidarity means

we all belong together

we all work together

we’re like union brothers

and sisters

but my family is broken

and scattered

in Poland and in America

and I’m here alone.

Loner or Leader

Time to choose. (109)

Two adolescents in early 1980’s. Some similarities; major differences.

When JJ Pankoski’s father goes on strike and is fired and blacklisted, they lose their home and car and move into the Polish grandparent’s house in Brooklyn where possibly JJ won’t be bullied as he was in his former school. A musician, JJ saves is his Casio keyboard, Walkman headphones, and punk-rock cassettes. But one other thing he loses is his sister Alina who remains in Lynbrook with a secret.

Pie, or Pierre Velez, lives with his Puerto Rican mother who suffers from mental illness, and his younger half-sister Pilar, yearns to have known his African father. He also is an artist, tagging buildings and recommended for a prestigious art class at the museum.

what means

the most to me?

family always comes first

then

my culture

my friends

my girl

my ‘hood

my future

my dreams (96)

JJ desperately needs a friend,

maybe [Pi] can help me

because he likes to get answers right

and explain to kids

who

don’t

understand.

and maybe he’ll even

like me. (84)

and, for a short while, Pie is that friend, the two boys connected by their love of the arts.

But Pie lives with discrimination.

…this is the one night

when anything goes—you can be anyone on Halloween

pretend you got special powers knowing full well that

the next day you’ll go back to being an ordinary kid

who hungers for heroes that Hollywood won’t create (104)

and when the class social studies project is assigned,

Now we got this project—we have to write

about a leader who changed the world and I don’t wanna write about

some dead white guy…even though I know that’s the only way

to get an A. (113)

But one night when they are tagging, Pie is arrested and JJ, as a white adolescent, is not only let go but driven home by the policeman (“Different Justice”). JJ is guilty for doing nothing.

Later, when he receives a much higher grade than Pie for a report on which Pie coached him, still was inferior to his friend’s

because Pie’s report

on Patrice Lumumba

was way better

than mine.

Pie told me to dig deeper

But he

dug

deepest

of all. (162-3)

JJ speaks out, but it is too little too late.

true friends

don’t leave you

hanging

true friends

always have

your back. (159)

Written in creatively-formatted free verse and co-authored by Zetta Elliott, who writes the voice of Pie, and Lyn Miller-Lachmann, who writes JJ’s narrative, Moonwalking is a work of history, prejudice and discrimination, poverty, mental illness, neuro-diversity, art, and friendship.

----------

Solidarity means

we all belong together

we all work together

we’re like union brothers

and sisters

but my family is broken

and scattered

in Poland and in America

and I’m here alone.

Loner or Leader

Time to choose. (109)

Two adolescents in early 1980’s. Some similarities; major differences.

When JJ Pankoski’s father goes on strike and is fired and blacklisted, they lose their home and car and move into the Polish grandparent’s house in Brooklyn where possibly JJ won’t be bullied as he was in his former school. A musician, JJ saves is his Casio keyboard, Walkman headphones, and punk-rock cassettes. But one other thing he loses is his sister Alina who remains in Lynbrook with a secret.

Pie, or Pierre Velez, lives with his Puerto Rican mother who suffers from mental illness, and his younger half-sister Pilar, yearns to have known his African father. He also is an artist, tagging buildings and recommended for a prestigious art class at the museum.

what means

the most to me?

family always comes first

then

my culture

my friends

my girl

my ‘hood

my future

my dreams (96)

JJ desperately needs a friend,

maybe [Pi] can help me

because he likes to get answers right

and explain to kids

who

don’t

understand.

and maybe he’ll even

like me. (84)

and, for a short while, Pie is that friend, the two boys connected by their love of the arts.

But Pie lives with discrimination.

…this is the one night

when anything goes—you can be anyone on Halloween

pretend you got special powers knowing full well that

the next day you’ll go back to being an ordinary kid

who hungers for heroes that Hollywood won’t create (104)

and when the class social studies project is assigned,

Now we got this project—we have to write

about a leader who changed the world and I don’t wanna write about

some dead white guy…even though I know that’s the only way

to get an A. (113)

But one night when they are tagging, Pie is arrested and JJ, as a white adolescent, is not only let go but driven home by the policeman (“Different Justice”). JJ is guilty for doing nothing.

Later, when he receives a much higher grade than Pie for a report on which Pie coached him, still was inferior to his friend’s

because Pie’s report

on Patrice Lumumba

was way better

than mine.

Pie told me to dig deeper

But he

dug

deepest

of all. (162-3)

JJ speaks out, but it is too little too late.

true friends

don’t leave you

hanging

true friends

always have

your back. (159)

Written in creatively-formatted free verse and co-authored by Zetta Elliott, who writes the voice of Pie, and Lyn Miller-Lachmann, who writes JJ’s narrative, Moonwalking is a work of history, prejudice and discrimination, poverty, mental illness, neuro-diversity, art, and friendship.

----------

Redwood and Ponytail (verse) by K.A. Holt

Tam (Redwood) and Kate (Ponytail) come from two different worlds.

Kate’s mom puts helicopter parents to shame. She has orchestrated Kate’s entire life so that in 7th grade she will become cheer captain and she will follow her mother’s life—unlike her much older sister who joined the Navy at 18. She lives in the perfect house, which is always being perfected, and her daughter certainly isn’t gay.

Tam’s mother is the opposite. Open and accepting and prone to trying out the adolescent lingo (and providing many of the laughs in reading this book). Tam is also looked after by neighbor Frankie and her wife. Frankie, it appears, is full of advice, based on experience trying to fit the stereotype. Tam is an athlete, tall as a redwood, ace volleyball player, who everyone high-five’s in the hallway, but she realizes she only has one good friend, Levy.

On the first day of school, Tam and Kate meet and, as they quickly, mysteriously, develop deep feelings for each other, they find each not only different from the stereotypes everyone assumes, but, opposite though they seem, opposite though their lives and families may be they each discover they may be a little different than they thought they were and more alike than they thought. Does Kate actually want to be cheer captain or would she rather run free in the team’s mascot’s costume? Does she really want to have lunch at her same old table or would she rather sit with Tam and Levy which is much more fun? Does Tam really want to beat Kate for the school presidency? Or is she punishing Kate for not being able to admit what their friendship may be?

----------

Tam (Redwood) and Kate (Ponytail) come from two different worlds.

Kate’s mom puts helicopter parents to shame. She has orchestrated Kate’s entire life so that in 7th grade she will become cheer captain and she will follow her mother’s life—unlike her much older sister who joined the Navy at 18. She lives in the perfect house, which is always being perfected, and her daughter certainly isn’t gay.

Tam’s mother is the opposite. Open and accepting and prone to trying out the adolescent lingo (and providing many of the laughs in reading this book). Tam is also looked after by neighbor Frankie and her wife. Frankie, it appears, is full of advice, based on experience trying to fit the stereotype. Tam is an athlete, tall as a redwood, ace volleyball player, who everyone high-five’s in the hallway, but she realizes she only has one good friend, Levy.

On the first day of school, Tam and Kate meet and, as they quickly, mysteriously, develop deep feelings for each other, they find each not only different from the stereotypes everyone assumes, but, opposite though they seem, opposite though their lives and families may be they each discover they may be a little different than they thought they were and more alike than they thought. Does Kate actually want to be cheer captain or would she rather run free in the team’s mascot’s costume? Does she really want to have lunch at her same old table or would she rather sit with Tam and Levy which is much more fun? Does Tam really want to beat Kate for the school presidency? Or is she punishing Kate for not being able to admit what their friendship may be?

----------

Same But Different by Holly Robinson Peete, Ryan Elizabeth Peete, & RJ Peete

New data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that autism affects one in 59 children.

Ryan Elizabeth Peete and RJ Peete’s novel Same But Different is based on their lives. Characters Charlie and Callie are twins; Charlie has autism, and Callie feels that she needs to be his guide, support, rule-maker, and the person who is always there to stand up for him against bullies and those who try to take advantage of his naiveté. This year Callie is starting tenth grade, and Charlie is repeating ninth, but she is still there for him.

In alternating chapters Charlie (RJ) and Callie (Ryan) discuss their lives on the “Autism Express.” Charlie takes us into his world where he “may have autism, but autism doesn’t have [him].” Ryan takes us into her world where it seems that autism may have her a little more than she wants. Ryan does focus on how Charlie affects her life and her relationships with family and peers. It is clear that she loves Charlie and willingly takes responsibility for helping him, but she does stress the negative aspects. I was left wishing that she felt more positive at times and found a few more advantages to having a brother with whom she is so close.

Although every child affected by autism is at a different point of the spectrum and is affected in different ways, a book explaining at least one family’s journey is a valuable addition to the classroom library, as a catalyst for generating important discussions among adolescents. Even though the characters are in high school, the book is appropriate for even young adolescents.

Parent-author Holly Robinson Peete provides an insightful introduction, “A Letter from Mom,” and conclusion, “A Mother’s Hope,” as well as a valuable Resource Guide. A very important point she makes is her worry how RJ's future may be affected as a man of color with autism, a person who doesn't necessarily read the signals of our world.

----------

New data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that autism affects one in 59 children.

Ryan Elizabeth Peete and RJ Peete’s novel Same But Different is based on their lives. Characters Charlie and Callie are twins; Charlie has autism, and Callie feels that she needs to be his guide, support, rule-maker, and the person who is always there to stand up for him against bullies and those who try to take advantage of his naiveté. This year Callie is starting tenth grade, and Charlie is repeating ninth, but she is still there for him.