- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

- Asian, Asian-American

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

14. THE UBUNTU PROJECT

An editorial by Jim Carnes in Teaching Tolerance magazine introduced me to the concept of African concept “ubuntu.” Mr. Carnes explained “Ubuntu, from the Nguni language, is one of those well-loved, elemental words that defy simple translation. The closest English equivalent is ‘humaneness,’ or ‘the quality of being human.’ A proverb common across Africa expresses the ubuntu ideal: ‘A person is a person through other people.’” Carnes quotes from a justice of the Constitutional Court of South Africa who explained the concept as follows: "[Ubuntu] is a culture which places some emphasis on communality and on the interdependence of the members of a community. It recognizes a person's status as a human being, entitled to unconditional respect, dignity, value and acceptance from the members of the community such person happens to be part of. It also entails the converse, however. The person has a corresponding duty to give the same respect, dignity, value and acceptance to each member of that community." (Carnes, 1997).

Having just spent the year creating and teaching a Humanities curriculum based on the theme of tolerance and human rights (Social Justice), it seemed that an effective way to end our study was by focusing on respect.

I then asked my students to examine this notion and share their insights and interpretation of ubuntu. The result was our Ubuntu Project.

Having just spent the year creating and teaching a Humanities curriculum based on the theme of tolerance and human rights (Social Justice), it seemed that an effective way to end our study was by focusing on respect.

I then asked my students to examine this notion and share their insights and interpretation of ubuntu. The result was our Ubuntu Project.

Project Requirements:

Getting them started with Ideas:

- You may work individually or in pairs.

- Be prepared to present your project on the due date.

- Verbally introduce your project with an explanation of your interpretation of Ubuntu and your decision on the medium in which they are presenting.

- The work is to be accomplished outside of class, and you are to individually keep a journal of your thinking, your decisions, and your process.

- You are permitted to use any materials that we have in the classroom as well as any outside resources you might provide on your own.

Getting them started with Ideas:

That first year my students presented during class periods to their classmates. There were quite a variety of projects which surpassed my Suggestions and promoted a diversity of talent. We were all surprised by some of the aptitudes demonstrated. Students felt free to tap into their creativity for three reasons: no one else was dependent on the outcome; they had invested a year getting to know each other and seeing similarities and valuing diversity; and there was no right or wrong “answer;” The project was a matter of personal interpretation and choice. Some of the presentation formats were more conventional, but many were completely unexpected:

The class concluded the project as reflective thinkers:

- a quilt – each square had a symbol of Ubuntu explained in the oral narration;

- a photographic essay;

- trading cards of Ubuntu heroes that each contained an explanation of how the acts of heroism exhibited “ubuntu-ness”;

- a newspaper composed of articles and cartoons garnered from newspapers, each one followed by an explanation of why it was included;

- an original dance composition and performance;

- a skit;

- a materials and picture collage;

- a video essay;

- a song collage;

- a video collage;

- original artwork;

- an interactive exhibit;

- an original clay sculpture;

- an exhibit integrating cultural quotations; and an original poem:

- an original poem

The class concluded the project as reflective thinkers:

In the following years, the Ubuntu project featured evening presentations so that parents could attend. In addition to some of the formats used the prior year, such as collages and sculptures, we had some especially creative presentations:

The most-unique may have been papercutting. Bridgette used the Chinese art-form in which all the intricate cuts are made internally with a knife or small scissors. She designed and cut a tree formed from people. Her accompanying journal expressed a journey of emotional peaks and valleys as she led the reader through days of blisters and bleeding fingers, only to find the whole thing worthwhile when her mother and sister bought her a frame for her project. Many, many years later I still remember her journal entry about picturing her artwork over the fireplace of her “future first home.”

The Ubuntu project continued to spark more creative expressions in following years with paintings, plays, video games, drawings and an “Ubuntu Moem,” a movie poem.

The Ubuntu project was effective, not because of the project itself, but because the assignment required adolescents to think about respect and humaneness and to interpret those concepts in their own ways. More often we hear about “earning respect” rather than being owed respect just for being a human being, being only responsible for not losing that privilege.

Although this assignment fits well within a Humanities curriculum, it is also the type of year-end project that can be assigned as an interdisciplinary team endeavor. Some teams have Talent Shows or Academic Fairs; one based on respect as the topic could cross content area boundaries and share talent.

- a movie titled “What Makes Us Human?”

- two Ubuntu board games

- an original song—lyrics and music

- a candle sculpture

- A Perfect World, a picture book

The most-unique may have been papercutting. Bridgette used the Chinese art-form in which all the intricate cuts are made internally with a knife or small scissors. She designed and cut a tree formed from people. Her accompanying journal expressed a journey of emotional peaks and valleys as she led the reader through days of blisters and bleeding fingers, only to find the whole thing worthwhile when her mother and sister bought her a frame for her project. Many, many years later I still remember her journal entry about picturing her artwork over the fireplace of her “future first home.”

The Ubuntu project continued to spark more creative expressions in following years with paintings, plays, video games, drawings and an “Ubuntu Moem,” a movie poem.

The Ubuntu project was effective, not because of the project itself, but because the assignment required adolescents to think about respect and humaneness and to interpret those concepts in their own ways. More often we hear about “earning respect” rather than being owed respect just for being a human being, being only responsible for not losing that privilege.

Although this assignment fits well within a Humanities curriculum, it is also the type of year-end project that can be assigned as an interdisciplinary team endeavor. Some teams have Talent Shows or Academic Fairs; one based on respect as the topic could cross content area boundaries and share talent.

13. CREATING ORIGINAL PICTURE BOOKS FROM RESEARCH

This is a Reading-Writing-and possibly Speaking RESEARCH PROJECT that can be adapted to any topic in any discipline at any grade level.

Directions:

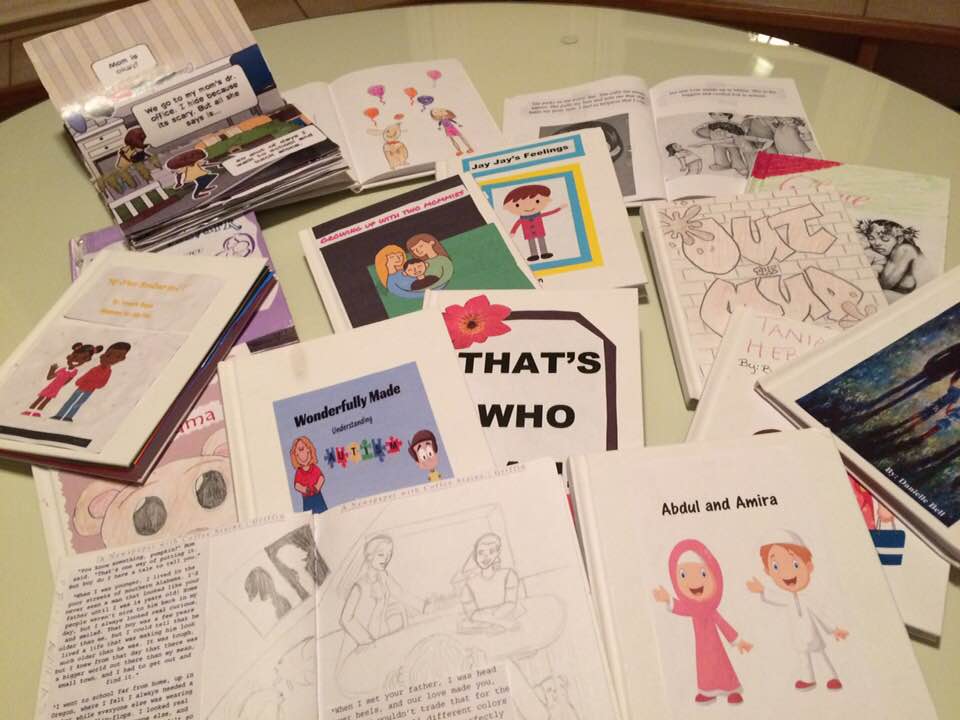

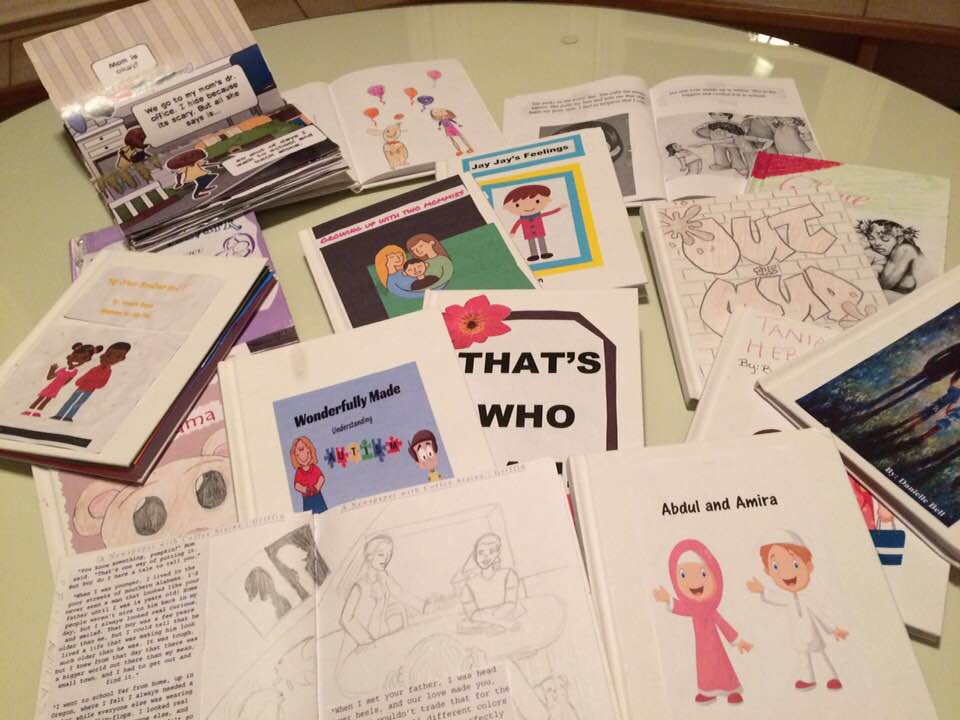

SAMPLE: My university Bibliotherapy students (many of whom were pre-service teachers) turned their research on challenges affecting children and teens into picture books to read with children and teens. Students found this assignment to more relevant and useful than a research paper. There was even one graphic book, and one student’s 8-year-old was her illustrator. Research projects were on such topics as bullying, facing loss, peer relationships, mental illness, identity, LBGT parents, siblings, immigration, interracial relationships, abuse, racism, homelessness, autism...

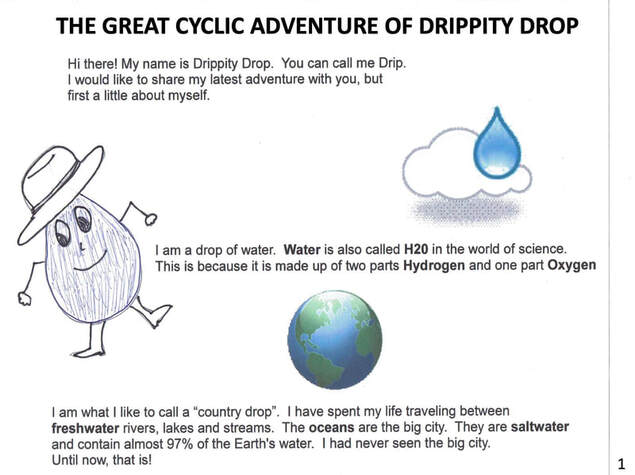

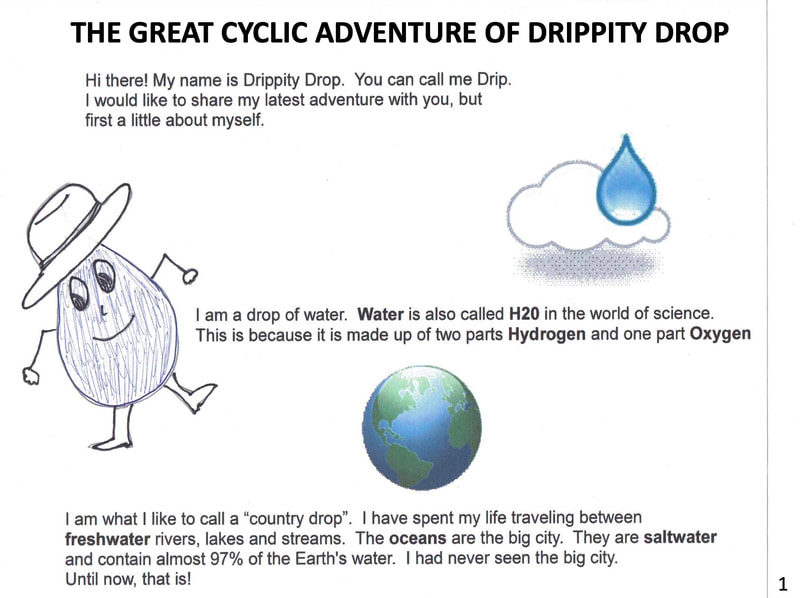

and a Science student wrote a storybook about the Water Cycle:

Directions:

- Students each or in pairs conduct research on a topic pertinent to the class unit or curriculum.

- Research is based on 3+ credible sources, included as a separate MLA or APA bibliography [whichever is being taught].

- Independently or in pairs, students create an Original Picture Book based on the research conducted and books read or discussed on the assigned research topic

- The book can be written for either for a younger child (or class) to read or for their peers. Writers must Adapt Word Choice and sentence complexity to their anticipated audiences.

- The books will be 20--8.5”x5.5” pages plus Title Page, Glossary, and Bibliography, but can be formatted as half pages of text with half pages of pictures or author can alternate text pages with picture pages.

- Books will include in-text citations [if appropriate to grade level].

- Completed books will be presented in class on _____________.

SAMPLE: My university Bibliotherapy students (many of whom were pre-service teachers) turned their research on challenges affecting children and teens into picture books to read with children and teens. Students found this assignment to more relevant and useful than a research paper. There was even one graphic book, and one student’s 8-year-old was her illustrator. Research projects were on such topics as bullying, facing loss, peer relationships, mental illness, identity, LBGT parents, siblings, immigration, interracial relationships, abuse, racism, homelessness, autism...

and a Science student wrote a storybook about the Water Cycle:

See also #6 below: HOLOCAUST RESEARCH & BOOK-WRITING PROJECT

12. COLLABORATIVE INFORMATIONAL WRITING: The Novel/Text Newspaper Project

In groups of 4 students will create a newspaper based on a novel (in ELA) or text (in Disciplinary Content Classes)

In groups of 4 students will create a newspaper based on a novel (in ELA) or text (in Disciplinary Content Classes)

Teaching:

1. Using newspapers as mentor texts, the teacher teaches the content different types of ARTICLES in a newspaper, such as

2. Using newspapers as a mentor texts, Students study the layout of newspapers and of articles and such elements as placement of articles, by-lines, photo credits, etc.

For the project,

1. Students divide themselves into News Staffs (4/Staff)

2. Each Staff of responsible for a 2-page newspaper

• containing at least 4 different types of articles

• based on the world of the novel or disciplinary unit, plus any research conducted

Guidelines/Directions:

The newspaper is assessed on

• format of newspaper and individual articles

• content - amount and accuracy of novel/text facts

• organization of individual articles and layout

• creativity

• conventions

50% of the grade earned is individual and based on the student's article and 50% of the grade is based from a group grade.

Benefits of Project:

1. Using newspapers as mentor texts, the teacher teaches the content different types of ARTICLES in a newspaper, such as

- National News articles

- Local News articles

- Feature/Human Interest stories

- Police Reports

- Advice Columns

- Obituaries

- Editorials or Commentaries

- Classified Ads

- Political Cartoons

- Sports News articles

2. Using newspapers as a mentor texts, Students study the layout of newspapers and of articles and such elements as placement of articles, by-lines, photo credits, etc.

For the project,

1. Students divide themselves into News Staffs (4/Staff)

2. Each Staff of responsible for a 2-page newspaper

• containing at least 4 different types of articles

• based on the world of the novel or disciplinary unit, plus any research conducted

Guidelines/Directions:

- No novel/text facts may be altered or ignored. In the case of writing about a novel, Readers/Writers can make up anything not covered that is consistent with the novel. Anything added to a content area unit must be factual and based on research.

- Each article must follow the format of a particular type of article as modeled in an actual newspaper—students are to check their handouts and notes—and contain the by-line of the writer.

- Each Staff member is responsible for drafting one article; all articles are to be different types. At least 3 of the articles must be “factual” (local news, national news, human interest, police report, and/or obituary) and at least 1 must be an “opinion” article (“political” cartoon, advice column, book/text chapter review, people poll based on a thoughtful question presented to real people, editorial commentary, and/or a set of 3 classified ads).

*Any article that is research-based will earn extra credit; sources must be cited. Teacher can discuss topics that would be appropriate for your novel or unit. - Proofreading, revising, editing, fact checking, and layout are accomplished with the collaborative assistance of all Staff members.

- Any other jobs and decisions or extra articles or segments are divided among the Staff or accomplished collaboratively.

- The newspaper must be word-processed and properly formatted as a front page and second page, in 2 justified columns, completely filled in (no “white space” except 1/2” margins and a center margin).

The newspaper is assessed on

• format of newspaper and individual articles

• content - amount and accuracy of novel/text facts

• organization of individual articles and layout

• creativity

• conventions

50% of the grade earned is individual and based on the student's article and 50% of the grade is based from a group grade.

Benefits of Project:

- Readers return to the text for more synthesis. See "The Benefits of After-Reading Response.)

- Students become more-critical readers of newspapers.

- Journalism writing.

- Group work provides instant and increased feedback and a sense of audience - elements often missing from the writing experience.

- The reactions of their peers help student writers understand they are writing for a community of readers, not only for a teacher.

- It reflects real-world writing situations where professionals often collaborate on presentations, reports, and projects.

- The project has both independent and interdependent components and meets multiple reading and writing standards.

11. WAYS TO MAKE RESEARCH MATTER

To be engaging research has to matter to the researcher, and to be effective it has to matter to their peers. In this article, I share two sample, adaptable research projects that benefit, not only the researchers, but also their classmates. (Roessing, L. English Journal, Vol. 96, No. 4, pp. 50-55. (Published by National Council of Teachers of English)

10. INTERDISCIPLINARY FOLKTALE PROJECTS

- ELA-SCIENCE COLLABORATIVE PROJECT

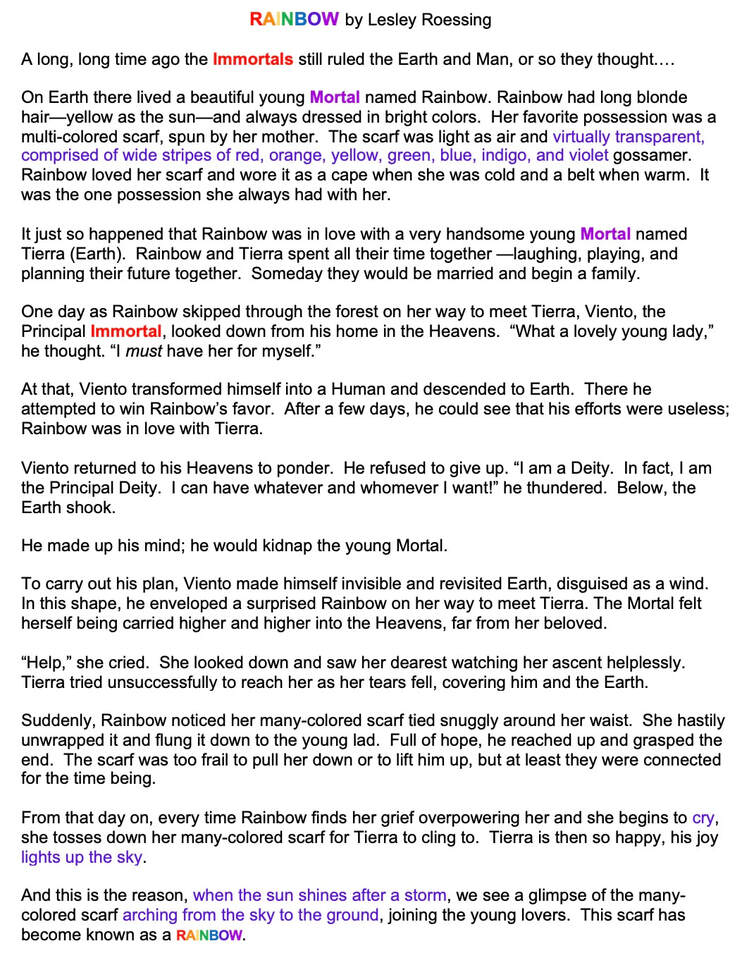

- In ELA students study MYTHS, ancient traditional stories which explained natural, scientific phenomena. The characters are deities (immortals) and heroic mortals, and as a folktale, they reflect the beliefs, traditions, and environment of a culture.

- In groups of 4-5, each group chooses a SCIENTIFIC PHENOMENON that they are learning about, or to learn about, in science class.

- Group members research everything they can learn about the phenomena, using at least 2 sources (or 1/student). At this point teachers or librarians can teach a focus lesson on research and making note cards with citations, depending on the grade level.

- Group members collaboratively write a myth, a story explaining the scientific phenomena, including as many researched facts as they can (adding in-text citations) and including the elements of a myth they have learned.

- Each group turns their story into a play or puppet show and presents the myth and then the real (as of the current year) belief about the science, explaining the phenomenon to an audience.

- Students are assessed on written myths.

- number of facts and sources

- elements of a myth (see #1)

- story elements: characters, setting, and plot—conflict and resolution

- ELA-SOCIAL STUDIES COLLABORATIVE PROJECT

- In ELA students study LEGENDS, ancient traditional stories which (1) memorialize (2) a real human who (3)performed an extraordinary or heroic deed. Legends take place in the (4) relatively (compared to myths) recent past in (5) an actual environment. Legends are based on facts but greatly (6) exaggerated [I always say that a good legend is 50%-50%]. As a folktale, legends reflect the beliefs, traditions, and environment of a culture.

- In groups of 4-5, students choose a person whom they are learning about, or will learn about, in social studies.

- Individually group members research the person and their extraordinary deed.

- Collaboratively, each group writes a legend, a story memorializing the important deed of the person, including the six elements of legends (see #1).

- Groups turn their story into a play or puppet show and present the legend and then share the real facts known about the person and deed.

Note: For distance learning, groups can chose or be assigned a person and then collaborate on their legend and research; they could divide the planning of the legend and conducting research, based on their interests, skills, talents, and intelligences. For their presentation they can prepare a digital graphic rendition. Two students could work on the legend—author and illustrator, and two could work on the factual—explanation and illustrations or a news story with pictures.

9. WRITING A COLLABORATIVE STORY: A (Visual) Reading-Writing-Speaking Activity

(also posted as Writing Strategy #4)

(also posted as Writing Strategy #4)

Directions:

- Divide students into groups of three.

- Each group chooses a picture.

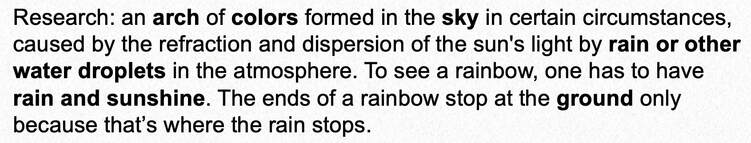

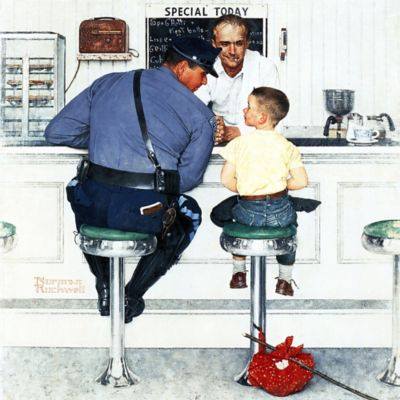

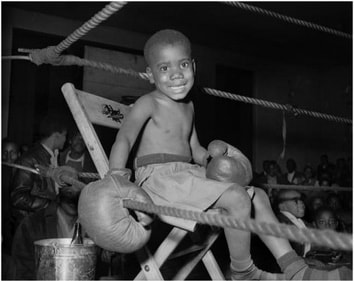

- Groups are to collaboratively draft a SHORT STORY (characters, plot/problem, setting) with dialogue. Note: It is difficult NOT to create a story with a Rockwell picture or a Teenie Harris photograph.

- Each group can then present their story in READERS' THEATER format with a narrator.

- Idea: In Science or Social Studies classes or as an interdisciplinary writing, provide pictures that include characters but also an event or setting from the content being studied.

- Adding a short RESEARCH component: Students can research the artist or photographer and the time period of the work (text).

FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT at the beginning of a fiction/narrative writing unit:

Even though participants are not being graded on their writing (or at all),I have found that participants do want their story to sound good when they share it, so they find themselves working on WORD CHOICE and SENTENCE FLUENCY to make it sound good.

This also will be an informal assessment of what your students know about SETTING, CHARACTER MOTIVATION and PLOT STRUCTURE; teachers can refer back to the stories when teaching or discussing LITERARY ELEMENTS in later reading lessons.

It will also assess what writers already know about including and developing DETAILS and ORGANIZATION—transitions, pacing, introductions, conclusions so teachers learn what they need to teach during the year.

When students are presenting, teachers can jot on a list of + and -. I required students to submit their "scripts" but told them that I was not looking at mechanics or neatness and not grading (

Teachers can offer participation points but I found that, with engaging pictures, they all participated).

Even though participants are not being graded on their writing (or at all),I have found that participants do want their story to sound good when they share it, so they find themselves working on WORD CHOICE and SENTENCE FLUENCY to make it sound good.

This also will be an informal assessment of what your students know about SETTING, CHARACTER MOTIVATION and PLOT STRUCTURE; teachers can refer back to the stories when teaching or discussing LITERARY ELEMENTS in later reading lessons.

It will also assess what writers already know about including and developing DETAILS and ORGANIZATION—transitions, pacing, introductions, conclusions so teachers learn what they need to teach during the year.

When students are presenting, teachers can jot on a list of + and -. I required students to submit their "scripts" but told them that I was not looking at mechanics or neatness and not grading (

Teachers can offer participation points but I found that, with engaging pictures, they all participated).

Benefits of COLLABORATIVE WRITING:

- Group work provides instant and increased feedback and a sense of audience - elements often missing from the writing experience.

- The reactions of their peers help student writers understand they are writing for a community of readers.

- The activity reflects real-world writing situations where professionals often collaborate on presentations, reports, and projects.

8. RESEARCHING AND WRITING A (SCHOOL) COMMUNITY BOOK

Students interview school staff and create an OUR SCHOOL COMMUNITY writing project. This is an effective way for students to get to know the school staff and collaborate in small writing groups for a whole-grade project.

In poet-author's Raven Howell picture book MY COMMUNITY, the narrator takes readers through her day and the people in her community, such as Mailman Juan. Each community member is described in a short, rhyming poem.

After a read-aloud of the book, the 76 first graders I worked with were inspired to create their own book about their school community. In small groups, the students asked interview questions of staff members, such as teachers, administrators, the chef, nurse, and custodian. Based on the information obtained, each group collaborated on a 6-line rhyming poem.

I served as facilitator (and scribe) for each group as they went through the brainstorming and writing process.

This project can be adapted to any grade level (with more in-depth interviews and more sophisticated writing) covering any Community: school, classroom, neighborhood, town/city, government, local hospital, local businesses,…or even "communities" of persons studied in content area classes, i.e., The Civil War Community, A Community of Scientists, The 20th Century Art Community.

If written in poetry, this would be an effective project for National Poetry Month and a way to study poetic elements, especially with older grade levels.

In poet-author's Raven Howell picture book MY COMMUNITY, the narrator takes readers through her day and the people in her community, such as Mailman Juan. Each community member is described in a short, rhyming poem.

After a read-aloud of the book, the 76 first graders I worked with were inspired to create their own book about their school community. In small groups, the students asked interview questions of staff members, such as teachers, administrators, the chef, nurse, and custodian. Based on the information obtained, each group collaborated on a 6-line rhyming poem.

I served as facilitator (and scribe) for each group as they went through the brainstorming and writing process.

- First, they made a list of facts about the community member. In many cases the children added information that their interview had not supplied, but they knew from their classes.

- Then they composed a line, and if it ended in a word that was difficult to rhyme, they revised the word order or found a synonym that worked. Students chanted rhyming words until they arrived at one that made sense and described the staff member.

- As they included information from the list in their poem, they checked each fact off the list.

- Each member of the 4-person groups contributed lines, words, and rhymes to their group poem. Some words came directly from the interviewees' interviews.

- Last, the writers became illustrators, drawing illustrations to accompany their poetry.

- When completed, I scanned and designed as a Powerpoint pdf so that our book could be emailed to parents, in color, w/o being printed (free publishing). Families could print the entire book or only print their child's pages. The book introduced parents to the school.

This project can be adapted to any grade level (with more in-depth interviews and more sophisticated writing) covering any Community: school, classroom, neighborhood, town/city, government, local hospital, local businesses,…or even "communities" of persons studied in content area classes, i.e., The Civil War Community, A Community of Scientists, The 20th Century Art Community.

If written in poetry, this would be an effective project for National Poetry Month and a way to study poetic elements, especially with older grade levels.

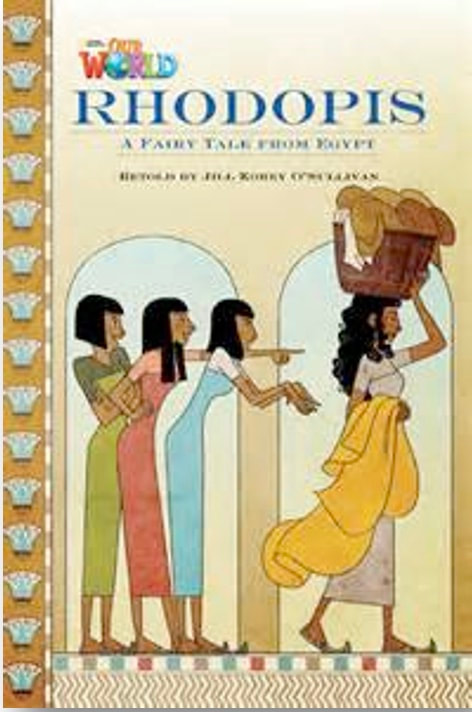

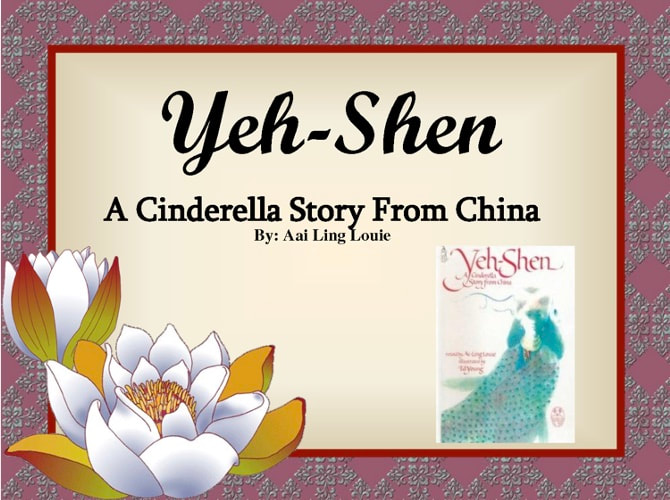

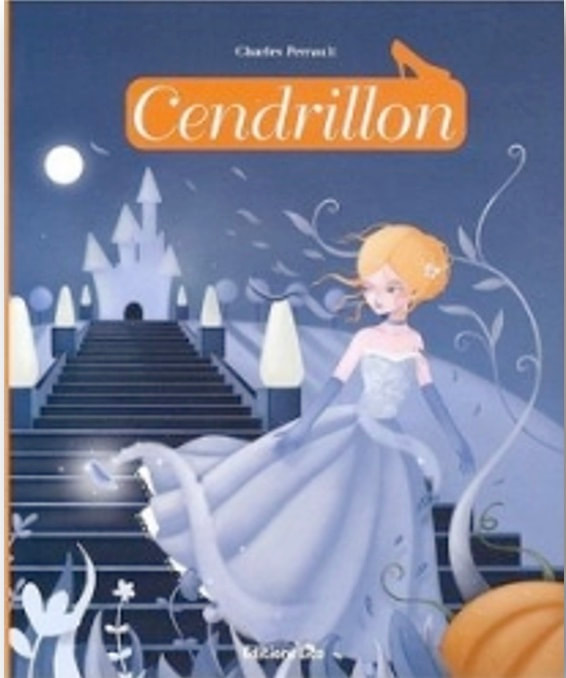

7. THE CINDERELLA CULTURAL DIVERSITY PROJECT

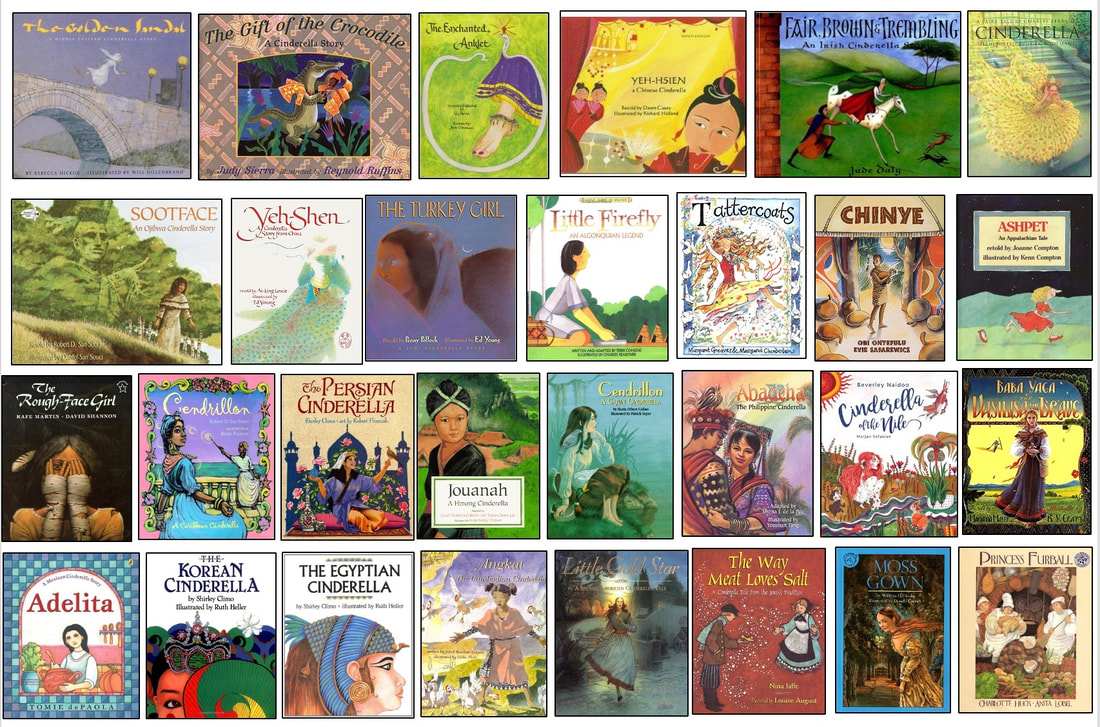

There are thousands of variants of the CINDERELLA folktale from all over the world. The first recorded story featuring a Cinderella figure dates to Greece in the 6th century BCE, and the Chinese Yeh-Shen dates from the 9th century. The Cinderella tale most familiar is the French variant Cendrillon, written down by Charles Perrault in 1697 (and adapted by Disney). Cinderella fairy tales have been discovered in Europe, Asia, Africa, North America, in almost every culture. There are certain motifs which categorize these tales as Cinderella tales. Other than Disney’s version, the Cinderella character is a strong, resilient young woman (or in some cases, young man) who, with the magical help of her mother’s spirit, is reclaiming her rightful position in society, a story of justice.

These tales, available in many formats—picture books, folktale anthologies and collections, and the more authentic versions— are effective for teaching about diverse traditional cultures to all grade levels. Folktales are important as reflections of the beliefs, traditions, and environment of cultures.

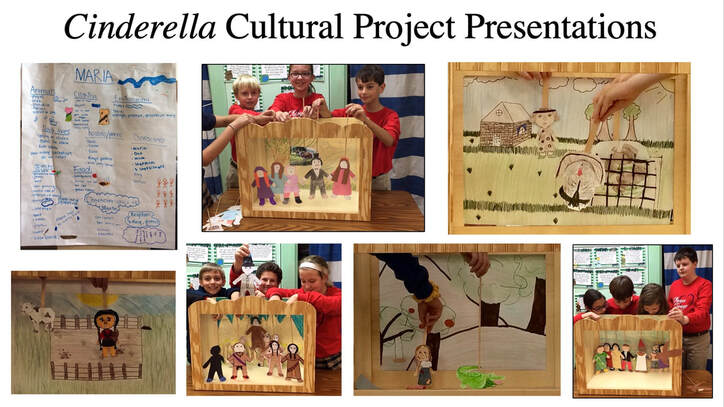

Students can learn the motifs of a Cinderella, read variants in Folktale Book Clubs [for more info on different types of Book Clubs, see TALKING TEXTS: A Teachers’ Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum], conduct some research on the culture from the tale and from other sources, and write a play based on their tale, performing as a puppet show, designing puppets and scenery which reflect the clothing and hairstyles, physical attributes of the characters, the physical environment of the culture, etc.

Students can then compare the different variants and cultures. See Cinderellas in Two Voices (Figures 3 and 4) in my AMLE article: https://www.amle.org/after-reading-response-poetry-in.../

This could be included as a cross-curricular project for English-Language Arts, World History or Ancient Civilizations, and Art—meeting multiple reading, writing, speaking, research, and disciplinary standards—in any grade level as Cinderella stories exist in picture book, short tale, and longer original versions with more complex vocabulary.

Lesson plans and reproducible forms for this Cultural-Comparison unit, as well as a bibliography of variants and suggestions for alternate final projects are included in NO MORE "US" AND "THEM": Classroom Lessons & Activities that Promote Peer Respect.

6. HOLOCAUST RESEARCH & BOOK-WRITING PROJECT

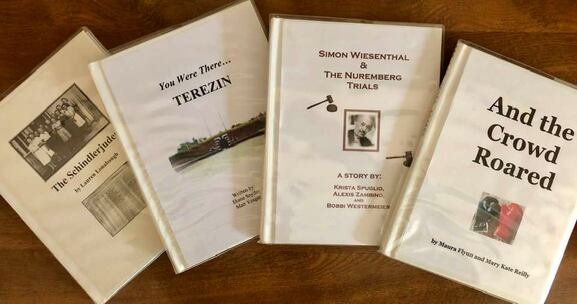

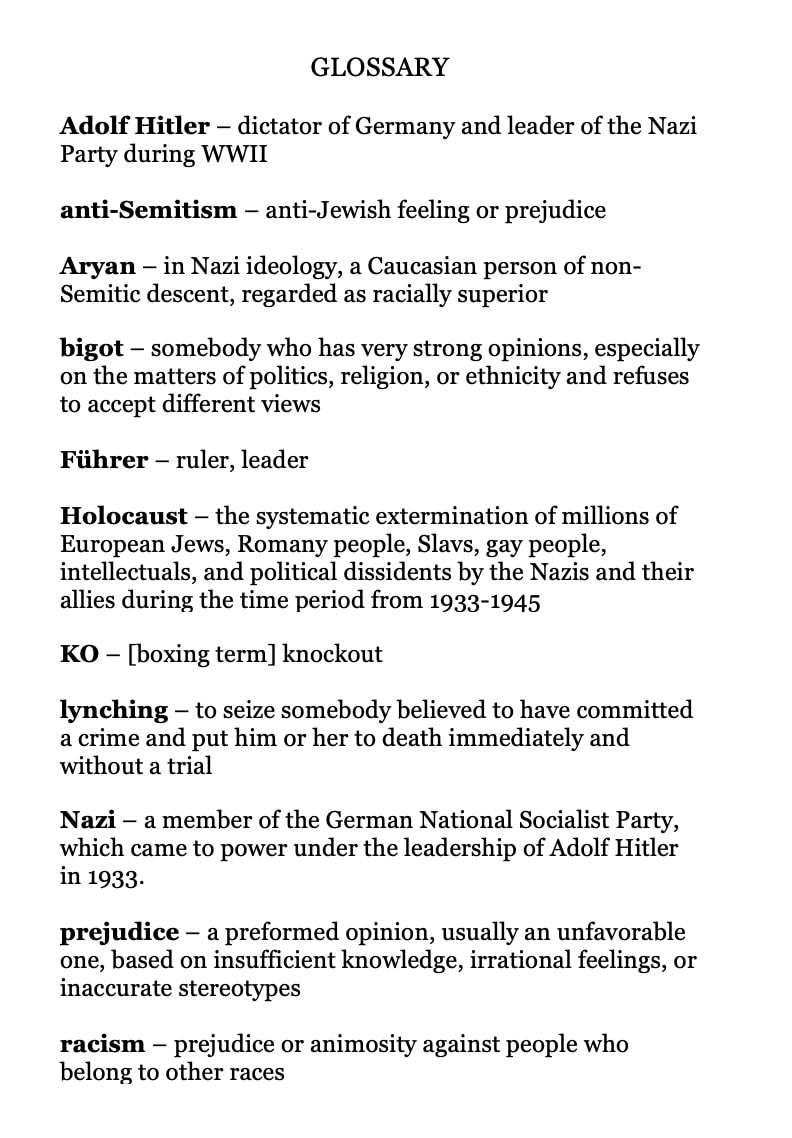

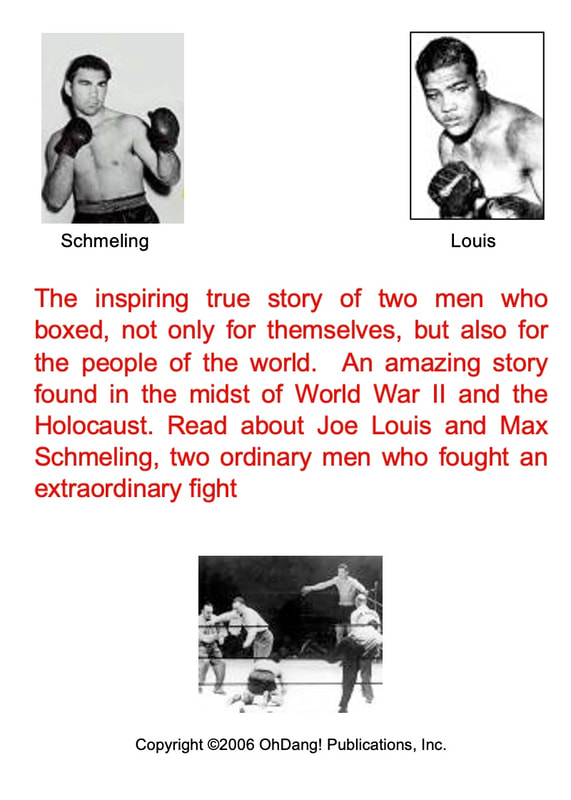

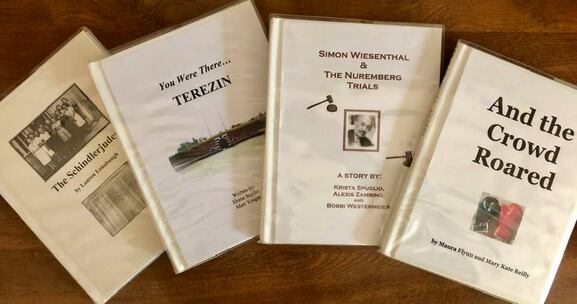

Students who are studying the Holocaust or reading Holocaust literature can conduct research for a purpose—to create an original story to share with current and future readers.

During our Holocaust unit, readers-writers researched topics of interest and created "You Were There" books for our Historical Fiction bookshelf and for future English-Language Arts and Social Studies students studying this unit. This was also a way to insert style and voice into research writing.

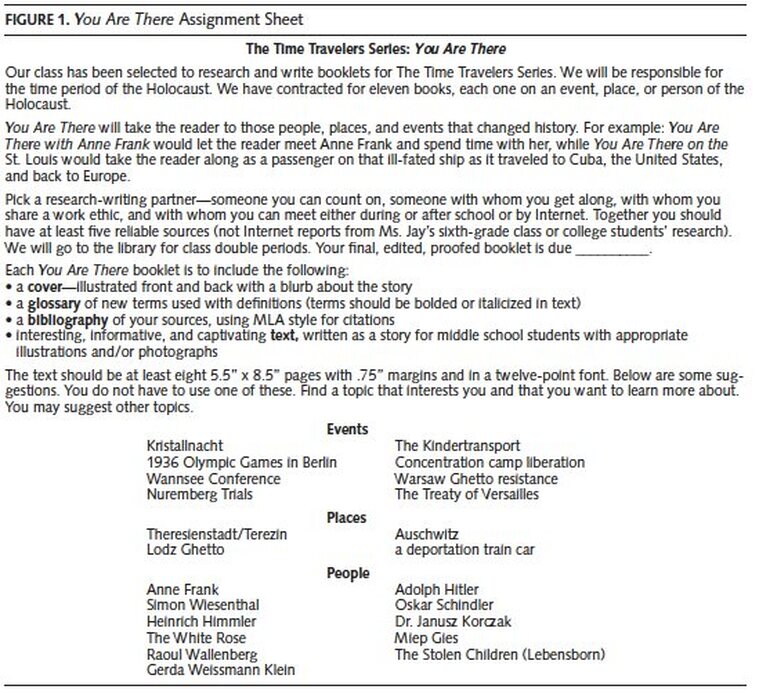

I created and distributed the assignment sheet [see below]. These were my directions for the project; students could choose topics that were not on the list since choice is a critical part of motivation and engagement.

During our Holocaust unit, readers-writers researched topics of interest and created "You Were There" books for our Historical Fiction bookshelf and for future English-Language Arts and Social Studies students studying this unit. This was also a way to insert style and voice into research writing.

I created and distributed the assignment sheet [see below]. These were my directions for the project; students could choose topics that were not on the list since choice is a critical part of motivation and engagement.

In pairs the students were to write stories using the forbidden second person. Every you that had been stricken from expository texts was called into play. I felt that, if the goal were to place the reader into the research, the writers would be compelled to use more details. They would be forced to think about what a person would see, hear, feel. This would appear to solve another predicament—looking at past events through 21st century eyes, seeing them though a contemporary value system and knowledge of the Holocaust. One challenge writers of historical fiction have is reporting the action through narrators or characters who lived through those times; my authors would not be burdened with that issue.

In pairs, students researched and wrote. Partnerships divided the work in diverse ways. Partner 1 researched; Partner 2 wrote. Partner 1 researched some sources; Partner 2 researched others; both wrote. After researching, one student outlined; the other wrote; the first then added dialogue. The permutations were endless. From overhearing conversation, I do know that the writing was recursive: research, draft, check facts, draft, revise….. The revisions consisted of adding, deleting, moving, verifying; in other words, real revision. Working in pairs (and one triad) meant students could each discover their strengths, and they had automatic peer reviewers and editors, ones who really cared about the final product. Endless conferencing went on. I saw and heard editing and publishing considerations that go on in professional publishing houses every day: 8-1/2”x 5-1/2” or 5-1/2”x8-1/2”? Photographs, clipart, or drawings? Title? Font? Chapters or subtitles? How to write the back-cover blurb to best “market” the book?

They called upon earlier mini-lessons on leads and endings, making transitions, writing dialogue, and including significant facts and details. They tried new techniques, such as altering perspective, using foreign words, and flashbacks.

In pairs, students researched and wrote. Partnerships divided the work in diverse ways. Partner 1 researched; Partner 2 wrote. Partner 1 researched some sources; Partner 2 researched others; both wrote. After researching, one student outlined; the other wrote; the first then added dialogue. The permutations were endless. From overhearing conversation, I do know that the writing was recursive: research, draft, check facts, draft, revise….. The revisions consisted of adding, deleting, moving, verifying; in other words, real revision. Working in pairs (and one triad) meant students could each discover their strengths, and they had automatic peer reviewers and editors, ones who really cared about the final product. Endless conferencing went on. I saw and heard editing and publishing considerations that go on in professional publishing houses every day: 8-1/2”x 5-1/2” or 5-1/2”x8-1/2”? Photographs, clipart, or drawings? Title? Font? Chapters or subtitles? How to write the back-cover blurb to best “market” the book?

They called upon earlier mini-lessons on leads and endings, making transitions, writing dialogue, and including significant facts and details. They tried new techniques, such as altering perspective, using foreign words, and flashbacks.

A student sample—And The Crowd Roared

This project is adaptable to any research topic.

>See additional details in the archived Roessing, L. “Making Research Matter.” English Journal, Vol. 96, No. 4 (Mar., 2007), pp. 50-55, published By: National Council of Teachers of English.

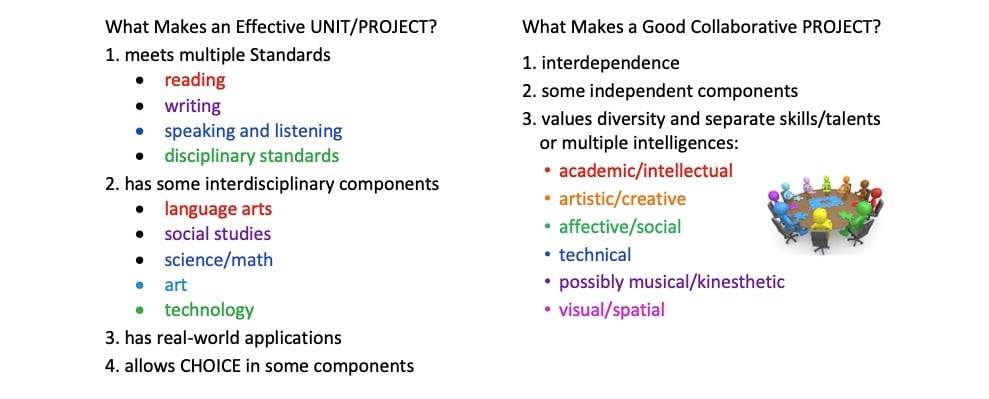

5. ELEMENTS OF EFFECTIVE & COLLABORATIVE PROJECTS

These are ideas to consider when designing a unit or project in English-Language Arts and any content area.

These are ideas to consider when designing a unit or project in English-Language Arts and any content area.

Information on the TOWN PROJECT, an ELA, science, math, S/S interdisciplinary Reading-Writing-Speaking collaborative project, was posted as Writing Strategy #14. READER'S THEATER: A Collaborative Reading-Writing-Speaking Activity is posted as Reading Strategy #16. The HOME FRONT FAIR: An Interactive Collaborative Interdisciplinary Action-Research Project is posted as Strategy #3 below. I will be posting other READING-WRITING-SPEAKING project lessons at this location in the future.

Lesson plans for projects that synthesize learning in all content areas and cause students to see similarities, value diversity, and reach cultural respect, are included in No More "Us" and "Them": Classroom Lessons and Activities to Promote Peer Respect.

Lesson plans for projects that synthesize learning in all content areas and cause students to see similarities, value diversity, and reach cultural respect, are included in No More "Us" and "Them": Classroom Lessons and Activities to Promote Peer Respect.

4. TEACHING ABOUT URLs

3. THE HOME FRONT FAIR: An Interactive Collaborative Interdisciplinary Action-Research Project

Students took a Multiple Intelligence "test" and were grouped by their dominant intelligences to work on one of three Discovery Centers:

Middle school parents and community visitors circled through the live-action exhibits, spending 20 minutes at each; the entire cycle took 1 hour (plus and introduction).

Students learned research skills and more about WWII and what the residents of their community may have experienced on the Home Front. One gentleman guest said, "I was overseas during the war and had no idea what was happening on the Home Front. I have learned a lot tonight."

The entire project is outlined in No More "Us" and "Them": Classroom Lessons & Activities to Promote Peer Respect. See a review by literacy expert Vicki Spandel.

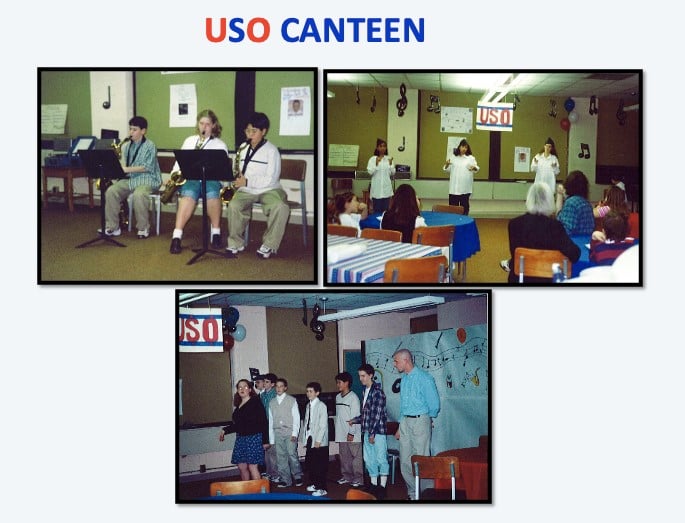

- USO CANTEEN (musical-rhythmic; kinesthetic),

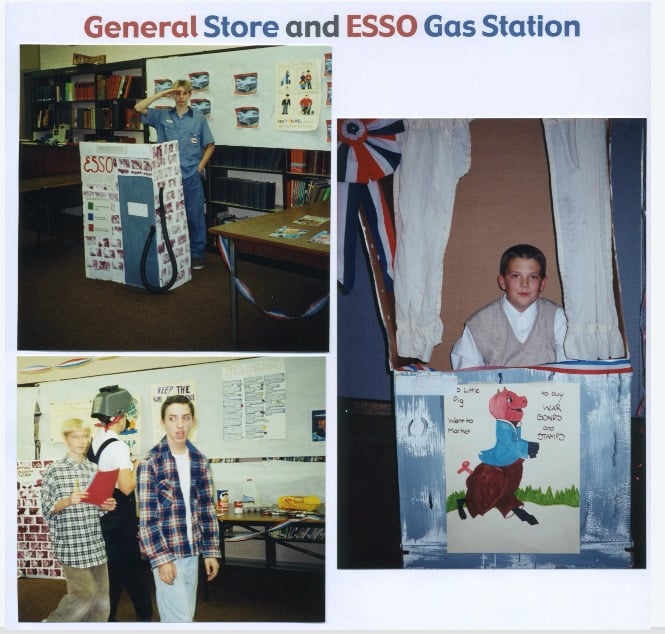

- GENERAL STORE (visual-spatial; logical-mathematical)

- RADIO NEWS SHOW (verbal-linguistic).

Middle school parents and community visitors circled through the live-action exhibits, spending 20 minutes at each; the entire cycle took 1 hour (plus and introduction).

- In the USO Canteen, guests listened to students sing and play on instruments "Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy" with a snack of donuts as were served in the Ridley USO Canteens and learned to swing dance.

- In the General Store, guests were given ration coupons and used them to buy groceries, based on the monthly income for their given profession, bought war bonds, and learned about the cars of the time period and gas rationing at TJ's gas station.

- The news crew presented a 20-minute radio news show complete with news stories, weather, and sports, as well war news.

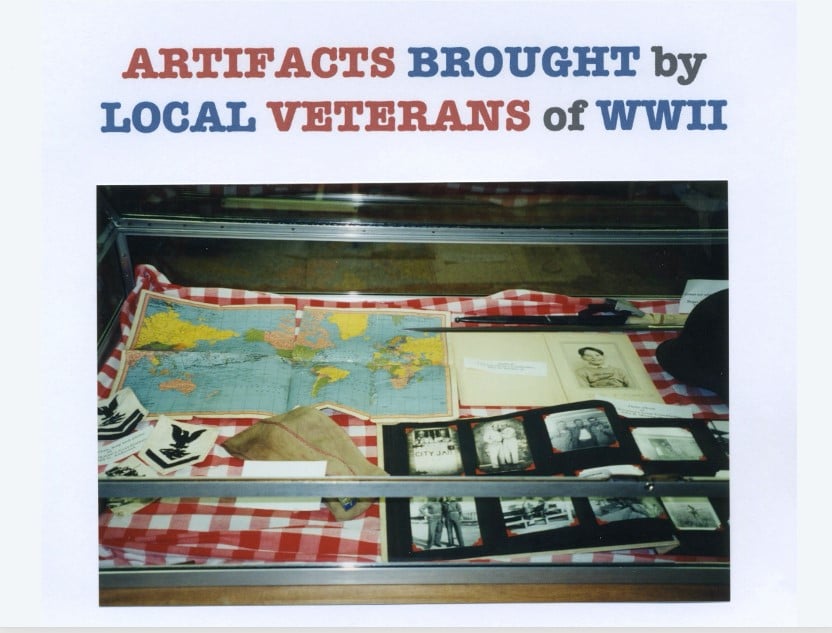

- Veterans were invited to bring mementos for a display.

Students learned research skills and more about WWII and what the residents of their community may have experienced on the Home Front. One gentleman guest said, "I was overseas during the war and had no idea what was happening on the Home Front. I have learned a lot tonight."

The entire project is outlined in No More "Us" and "Them": Classroom Lessons & Activities to Promote Peer Respect. See a review by literacy expert Vicki Spandel.

2. RESEARCH THAT IS PURPOSEFUL

My university students turned their research on challenges affecting children and teens into picture books to read with children and teens. Students found this assignment to more relevant and useful than a research paper. There was even a graphic book, and one student’s 8-year-old child was her illustrator. Research projects were conducted on such topics as bullying, facing loss, peer relationships, mental illness, identity, LGBTQ parents, siblings, immigration, interracial relationships, abuse, racism, homelessness, autism...and the books included in-text citations and a Bibliography (Photo 1).

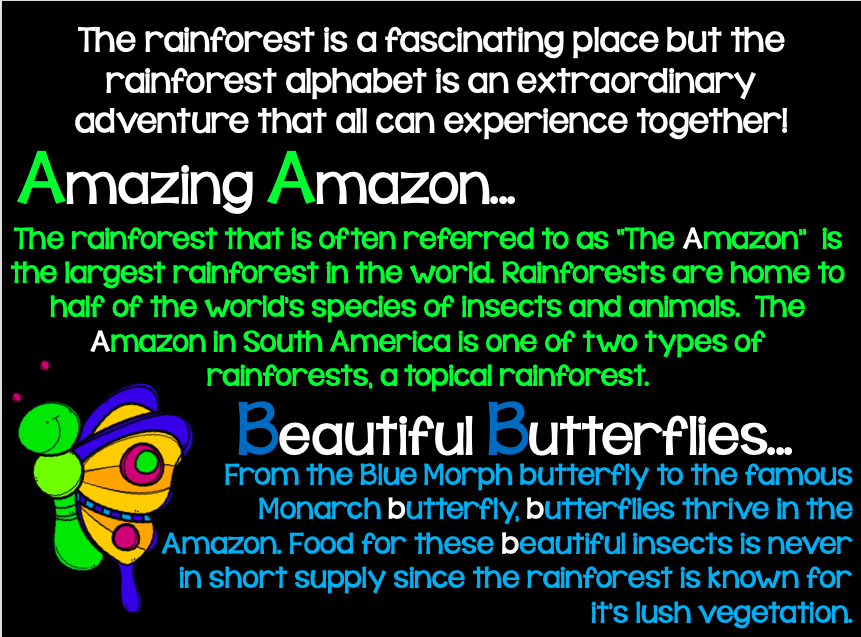

On other topics, such as the rainforest, students (grades 3 to university) created A-B-C books for reading audiences (Photo 2). And students can show and share what they have learned through their study and research in the content areas, such as a student book on the water cycle, starring Drippity Drop, a drop of water (Photo 3).

During our Holocaust unit, 8th grade readers-writers researched topics of interest and created You Were There books for our Historical Fiction bookshelf and for future students studying this SS-ELA unit. See details in the archived English Journal article "Making Research Matter." English Journal, Vol. 96, No. 4 (Mar., 2007), pp. 50-55.

On other topics, such as the rainforest, students (grades 3 to university) created A-B-C books for reading audiences (Photo 2). And students can show and share what they have learned through their study and research in the content areas, such as a student book on the water cycle, starring Drippity Drop, a drop of water (Photo 3).

During our Holocaust unit, 8th grade readers-writers researched topics of interest and created You Were There books for our Historical Fiction bookshelf and for future students studying this SS-ELA unit. See details in the archived English Journal article "Making Research Matter." English Journal, Vol. 96, No. 4 (Mar., 2007), pp. 50-55.

Elementary, middle grade, and high school students can research, create books on any topics, and read them to elementary students or even their peers. Also see my Strategies for Informative Writing & Research #6 and 7. And for additional ideas, see my article.

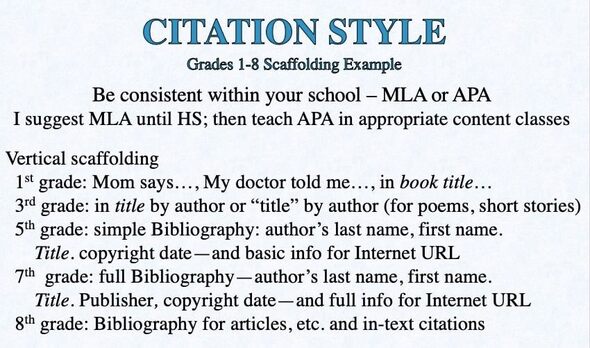

1. SCAFFOLDING TEACHING CITATIONS

A strategy for teaching citations—SCAFFOLDING through the grades; teaching the how, when, where, and why of citing

Pictured is my example of ways to scaffold:

A strategy for teaching citations—SCAFFOLDING through the grades; teaching the how, when, where, and why of citing

Pictured is my example of ways to scaffold:

- Start with terms that younger learners can understand and sources they can access but are "experts" or "authorities" on the topic being discussed or written. Writing/Drawing directions for making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich? Quote Mom who has been making them for over 20 years. Writing about feeding pets? Call the vet for a quote and refer to "our vet" or Dr. John, our dog's vet." Start with citing book titles (underlined in writing by 2nd grade; italics when typing).

- As students progress, add authors and then publishers and publication years to text sources and more expert authorities and a credential when citing people.

- By middle grades, students are citing information gleaned from Internet sources, full book citations, and other text materials.

- When students are ready, add speeches and other types of texts and more complicated Internet citations.

- In high school, students could use MLA for English and Social Studies research writings and APA for Sciences and Math.

Proudly powered by Weebly