- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

- Asian, Asian-American

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

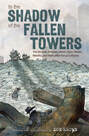

There are many reasons, and ways, to include graphic novels in the curriculum.

Graphics appeal to or are useful for readers not interested in, or engaged by, traditional prose texts; artistic readers; visual readers or learners; and ELLs. But all readers may enjoy graphic novels from time to time.

One of the most important reasons to include graphic novels is to teach visual literacy. Our students now—and as future adults —are constantly bombarded with images in the media, and it is imperative that they learn to interpret and analyze these visuals.

I would suggest first introducing a Whole-Class reading experience with a short graphic novel or even a comic book or comic page to explore the basics of graphics. Then teachers can include a graphic option in Book Club reading. Most, if not all of my topics under my Book Reviews include prose, verse, graphic, and, in many cases, multi-formatted choices for Book Clubs and/or for independent, self-selected reading. For example, if Book Clubs were all reading books on the topic of "Identity," one club might read a prose novel, one a memoir, one a verse novel, and one a graphic novel or memoir. At least when teachers offer the selections from which they will choose to form their book clubs, one of the books, if possible, would be a graphic text. [See "The 5 Steps of Facilitating a Book Club."]

Reading Workshop Focus Lessons (10-15 minute) can be presented on each graphic element:

Readers will learn to receive information through both words and images and analyze connections and relationships between the two. One example is when studying characterization and character traits. In prose text, readers consider how characters act, what they say, and what others say about the characters. In graphics, readers can read facial expressions and body language to further analyze character traits and how they influence the characters' decisions.

More graphic novels are being written, and more adaptations of prose novels, both classics and popular MG and YA literature, are being published. These are some I have read and *reviews of twelve of them—realistic fiction, historical fiction, sports fiction, memoir, Pride, classic, and fantasy—are below.

Graphics appeal to or are useful for readers not interested in, or engaged by, traditional prose texts; artistic readers; visual readers or learners; and ELLs. But all readers may enjoy graphic novels from time to time.

One of the most important reasons to include graphic novels is to teach visual literacy. Our students now—and as future adults —are constantly bombarded with images in the media, and it is imperative that they learn to interpret and analyze these visuals.

I would suggest first introducing a Whole-Class reading experience with a short graphic novel or even a comic book or comic page to explore the basics of graphics. Then teachers can include a graphic option in Book Club reading. Most, if not all of my topics under my Book Reviews include prose, verse, graphic, and, in many cases, multi-formatted choices for Book Clubs and/or for independent, self-selected reading. For example, if Book Clubs were all reading books on the topic of "Identity," one club might read a prose novel, one a memoir, one a verse novel, and one a graphic novel or memoir. At least when teachers offer the selections from which they will choose to form their book clubs, one of the books, if possible, would be a graphic text. [See "The 5 Steps of Facilitating a Book Club."]

Reading Workshop Focus Lessons (10-15 minute) can be presented on each graphic element:

- panels—size, shape, sequencing

- gutters

- speech balloons—fonts and size of type, punctuation, empty balloons, visual and punctuation clues to tone and mood (instead of taglines)

- under-panel narration

- layout

- artwork; use of color; composition; motion lines; etc.

Readers will learn to receive information through both words and images and analyze connections and relationships between the two. One example is when studying characterization and character traits. In prose text, readers consider how characters act, what they say, and what others say about the characters. In graphics, readers can read facial expressions and body language to further analyze character traits and how they influence the characters' decisions.

More graphic novels are being written, and more adaptations of prose novels, both classics and popular MG and YA literature, are being published. These are some I have read and *reviews of twelve of them—realistic fiction, historical fiction, sports fiction, memoir, Pride, classic, and fantasy—are below.

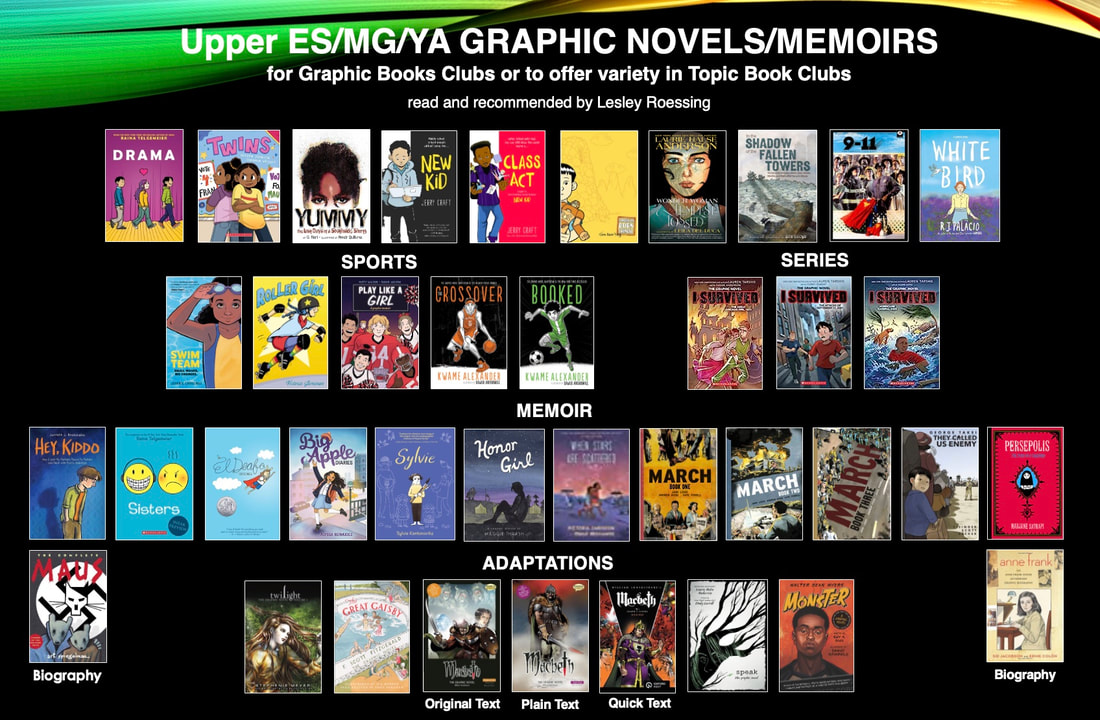

Drama; Twins; Yummy: The Last Days of a Southside Shorty*; New Kid*; Class Act*; American Born Chinese; Wonder Woman: Tempest Tossed*; In the Shadow of the Fallen Towers*; 9-11: The World's Finest Comic Book Writers and Artists Tell Stories To Remember*; White Bird; Swim Team*; Roller Girl; Play Like a Girl*; Crossover; Booked; I Survived series; Hey, Kiddo; Sisters; El Deafo; Big Apple Diaries*; Sylvie*; Honor Girl; When Stars Are Scattered*; March—Books One, Two, and Three; They Called Us Enemy; Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood; The Complete Maus (Maus I and II); Anne Frank; Twilight; The Great Gatsby; Macbeth (Original Text, Plain Text, and Quick Text versions available in all Shakespeare); Speak; Monster

9-11: The World's Finest Comic Book Writers and Artists Tell Stories To Remember by DC Comics

The creative talent of DC Comics donated their time and work for this volume which tells the stories and shares the images of September 11, 2001, through 39 graphic stories that reveal diverse perspectives. This volume is dedicated to the victims of the September 11th attacks, their families, and the heroes who supported and supplied aid. All profits are to be contributed to 9-11 charitable funds. The book is a celebration of heroes and a memorial to victims.

Story contributors include writers and artists who will be well-known to comic fans and graphic readers, such as Will Eisner, one of the pioneers of American comic books and graphic novels; Stan Lee, primary creative leader of Marvel Comics; and Neil Gaiman, New York Times bestselling author of more than twenty books.

Divided into five sections: “Nightmares,” “Heroes,” “Recollections,” “Unity,” and “Dreams,” the diversity of stories and artwork will appeal to a variety of YA readers. There are integration of the DC heroes throughout. Readers can select the stories and artwork that speak to them. As with most anthologies, the quality and appeal of the stories and the work vary. Many are well executed and moving, others are weaker; some portray complicated emotions, and others lack depth; some may be triggering, others may not connect the reader to the events. Some are may come across as more political than others.

One of the first graphics, “Wake Up,” relates the story of a young boy who dreams of his mother, a NYC police officer who lost her life. He wakes up, “doing what Mom said, standing tall because I want the bad guys to know…I’m not broken. My heart is unbreakable.” (23)

In the Unity section, in the story “For Art’s Sake” a comic book artist struggles with the value of his profession after witnessing the fall of the Trade Center. He tells his father, also an illustrator, “Don’t you feel a little guilty? Because we’re sitting here telling meaningless stories about imaginary heroes while out there, hundreds of real heroes are dead.…All comic books, all art for that matter! Painting, movies, tv…it all seems so frivolous, you know?”” (121-2) His father counsels him, “Listen, I’m not saying artists are near as brave as the men or women who ran into those buildings. We’re not. But we do have a role to play. We answered a calling just like they did.…We help our country cope with tragedies like this one. We make people think, we help them laugh again, or maybe we just give ‘em a place to escape for a little while.” (124)

I would recommend this book to readers who are engaged by graphics, are open to a range of interpretations of events, and already have some knowledge of the events of 9/11.

----------

The creative talent of DC Comics donated their time and work for this volume which tells the stories and shares the images of September 11, 2001, through 39 graphic stories that reveal diverse perspectives. This volume is dedicated to the victims of the September 11th attacks, their families, and the heroes who supported and supplied aid. All profits are to be contributed to 9-11 charitable funds. The book is a celebration of heroes and a memorial to victims.

Story contributors include writers and artists who will be well-known to comic fans and graphic readers, such as Will Eisner, one of the pioneers of American comic books and graphic novels; Stan Lee, primary creative leader of Marvel Comics; and Neil Gaiman, New York Times bestselling author of more than twenty books.

Divided into five sections: “Nightmares,” “Heroes,” “Recollections,” “Unity,” and “Dreams,” the diversity of stories and artwork will appeal to a variety of YA readers. There are integration of the DC heroes throughout. Readers can select the stories and artwork that speak to them. As with most anthologies, the quality and appeal of the stories and the work vary. Many are well executed and moving, others are weaker; some portray complicated emotions, and others lack depth; some may be triggering, others may not connect the reader to the events. Some are may come across as more political than others.

One of the first graphics, “Wake Up,” relates the story of a young boy who dreams of his mother, a NYC police officer who lost her life. He wakes up, “doing what Mom said, standing tall because I want the bad guys to know…I’m not broken. My heart is unbreakable.” (23)

In the Unity section, in the story “For Art’s Sake” a comic book artist struggles with the value of his profession after witnessing the fall of the Trade Center. He tells his father, also an illustrator, “Don’t you feel a little guilty? Because we’re sitting here telling meaningless stories about imaginary heroes while out there, hundreds of real heroes are dead.…All comic books, all art for that matter! Painting, movies, tv…it all seems so frivolous, you know?”” (121-2) His father counsels him, “Listen, I’m not saying artists are near as brave as the men or women who ran into those buildings. We’re not. But we do have a role to play. We answered a calling just like they did.…We help our country cope with tragedies like this one. We make people think, we help them laugh again, or maybe we just give ‘em a place to escape for a little while.” (124)

I would recommend this book to readers who are engaged by graphics, are open to a range of interpretations of events, and already have some knowledge of the events of 9/11.

----------

Big Apple Diaries (memoir) by Alyssa Bermudez

Big Apple Diaries is based on the author’s actual journals which she has illustrated as a graphic diary memoir encompassing the time from September 2000 to June 2002.

Alyssa Bermudez was the child of divorced parents, dividing her time between her Puerto Rican father who lived in Manhattan and her Italian-British mother who lived in Queens. This diary begins in 7th grade where “It seems that suddenly every grade you get and everything you do matters…. Now our friends are obsessed with who has a crush on who. And who is the coolest. There is all of this pressure to be popular and smart or face a dim future being a weirdo with no job.” (10)

Alyssa is not particularly popular, but not particularly unpopular either, has a much older half-brother and two best friends, Lucy and Carmen, and is an artist who wants to become a shoe designer. In this 7th grade year, she experiences her first crush—Alejandro from Columbia. Her diary takes us through the typical middle school year familiar to most of our adolescent readers. “Yesterday I did something very stupid. I knew it was stupid at the time and I still did it anyway. It’s like the drive to be popular makes me see things through stupid lenses.” (83) Typical preteen, she does many “stupid things”: shave her eyebrows, accidently dye her hair orange, cut school.

Two months before her thirteenth birthday, the attacks of September 11th occur. Alyssa’s mother worked in a building that faced the Twin Towers. She escaped and caught the last train to Queens. Her father did work in the World Trade Center but was meeting a client in Jersey City that morning (and bought skates to skate the 19.5 miles back to his Manhattan home). Overcome with emotion, Alyssa writes no entries for that day and the following few.

After that time Alyssa recognizes, “I sort of feel like I have no control over anything. I want to come back to the normal life I knew and the Twin Towers that I visited with Dad all the time.”(195) She finds herself changing, maturing: “When things can change in an instant, it’s hard to accept it. I want to make the right decisions and prove my worth. I want to be brave.” (211)

On her thirteenth birthday she begins to wonder “Who am I?” and begins thinking about her character and how she may want to change. Her diary takes the reader through graduation to a future where “Some things I’ll take with me and other things I will leave behind.” (274)

Big Apple Diaries, a graphic memoir of an NYC adolescent who experienced 9/11 as part of her middle grade years adds yet another perspective or dimension to the other novels in this 9/11 book collection.

----------

Big Apple Diaries is based on the author’s actual journals which she has illustrated as a graphic diary memoir encompassing the time from September 2000 to June 2002.

Alyssa Bermudez was the child of divorced parents, dividing her time between her Puerto Rican father who lived in Manhattan and her Italian-British mother who lived in Queens. This diary begins in 7th grade where “It seems that suddenly every grade you get and everything you do matters…. Now our friends are obsessed with who has a crush on who. And who is the coolest. There is all of this pressure to be popular and smart or face a dim future being a weirdo with no job.” (10)

Alyssa is not particularly popular, but not particularly unpopular either, has a much older half-brother and two best friends, Lucy and Carmen, and is an artist who wants to become a shoe designer. In this 7th grade year, she experiences her first crush—Alejandro from Columbia. Her diary takes us through the typical middle school year familiar to most of our adolescent readers. “Yesterday I did something very stupid. I knew it was stupid at the time and I still did it anyway. It’s like the drive to be popular makes me see things through stupid lenses.” (83) Typical preteen, she does many “stupid things”: shave her eyebrows, accidently dye her hair orange, cut school.

Two months before her thirteenth birthday, the attacks of September 11th occur. Alyssa’s mother worked in a building that faced the Twin Towers. She escaped and caught the last train to Queens. Her father did work in the World Trade Center but was meeting a client in Jersey City that morning (and bought skates to skate the 19.5 miles back to his Manhattan home). Overcome with emotion, Alyssa writes no entries for that day and the following few.

After that time Alyssa recognizes, “I sort of feel like I have no control over anything. I want to come back to the normal life I knew and the Twin Towers that I visited with Dad all the time.”(195) She finds herself changing, maturing: “When things can change in an instant, it’s hard to accept it. I want to make the right decisions and prove my worth. I want to be brave.” (211)

On her thirteenth birthday she begins to wonder “Who am I?” and begins thinking about her character and how she may want to change. Her diary takes the reader through graduation to a future where “Some things I’ll take with me and other things I will leave behind.” (274)

Big Apple Diaries, a graphic memoir of an NYC adolescent who experienced 9/11 as part of her middle grade years adds yet another perspective or dimension to the other novels in this 9/11 book collection.

----------

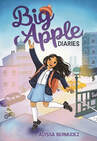

Class Act by Jerry Craft

“Getting As in all my classes is SO much easier than all the personal stuff. I wish friendship came with a textbook.… School would be so much easier without all the non-school stuff.” (Drew, 169)

In the sequel to New Kid, seventh grade friends Jordan, Liam, and Drew have to learn to navigate a new year in their prestigious private school. But eighth grade becomes much more complicated.

Jordan, who is struggling with being younger, smaller, and more physically immature than the other eighth grade boys, has to keep the peace between his best friends when Drew visits the mansion where Liam lives, judging him for how his parents’ lifestyle. Liam, whose parents ignore him, knows that wealth is not the secret to happiness.

As the boys visit each other’s neighborhoods and meet kids from another school which RAD wants to adopt as a “sister school” to promote diversity, they begin to notice microaggressions, racism, and classism all around them. Their “ever-learning and ever-evolving” school creates an Office of Diversity and Inclusion and also a Students of Color Konnect club, and things become worse. “No one is happy just being who they are. It’s like we all have the way we want people to think we are…and then we have our real selves.” (177)

When Jordan’s parents get involved in day of food and sports, all three boys become exposed to new experiences. And they—especially Drew—realize, “We should probably try to stop being so hard on each other.…And on ourselves.” (244)

Jordan the aspiring cartoonist continues to share his life through black and white drawings within each chapter.

----------

“Getting As in all my classes is SO much easier than all the personal stuff. I wish friendship came with a textbook.… School would be so much easier without all the non-school stuff.” (Drew, 169)

In the sequel to New Kid, seventh grade friends Jordan, Liam, and Drew have to learn to navigate a new year in their prestigious private school. But eighth grade becomes much more complicated.

Jordan, who is struggling with being younger, smaller, and more physically immature than the other eighth grade boys, has to keep the peace between his best friends when Drew visits the mansion where Liam lives, judging him for how his parents’ lifestyle. Liam, whose parents ignore him, knows that wealth is not the secret to happiness.

As the boys visit each other’s neighborhoods and meet kids from another school which RAD wants to adopt as a “sister school” to promote diversity, they begin to notice microaggressions, racism, and classism all around them. Their “ever-learning and ever-evolving” school creates an Office of Diversity and Inclusion and also a Students of Color Konnect club, and things become worse. “No one is happy just being who they are. It’s like we all have the way we want people to think we are…and then we have our real selves.” (177)

When Jordan’s parents get involved in day of food and sports, all three boys become exposed to new experiences. And they—especially Drew—realize, “We should probably try to stop being so hard on each other.…And on ourselves.” (244)

Jordan the aspiring cartoonist continues to share his life through black and white drawings within each chapter.

----------

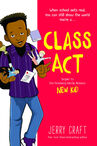

In The Shadow of The Fallen Towers by Don Brown

This graphic recounts events following the 9/11 Attacks on the Towers and the Pentagon from the moment of the “jetliner slamming into the North Tower of the World Trade Center” to the one-year anniversary ceremonies at the Pentagon; in Shanksville, Pennsylvania; and at Ground Zero. It also covers the fighting of U.S. troops in Afghanistan and the capture and interrogation of prisoners from an al-Qaeda hideout in Pakistan.

The drawings allow readers to bear witness to the heroism of the first responders, firefighters, and police as they move from rescue to recovery over the ten months following the attacks and learn the stories of some of the survivors they saved. It is the story of the nameless “strangers [who] help[ed] one another, carrying the injured, offering water to the thirsty, and comforting the weeping.” (23)

We learn and view details that we may have not known, such as “Bullets start to fly when the flames and heat set off ammunition from fallen police officers’ firearms,” (11) the “Pentagon workers [who] plunge[d] into the smoke-filled building to restore water pressure made feeble by pipes broken in the attack,” (36) and former military who donned their old uniforms and “bluff[ed their way] past the roadblocks” to “sneak onto the Pile” to help. (50, 52)

For more mature readers, this book adds to the story of 9/11 in a more “graphic” way, and would supplement the novels, memoirs, and picture books to commemorate September 11th reviewed in my YA Wednesday guest blog "Novels, Memoirs, Graphics, and Picture Books to Commemorate 9/11."

----------

This graphic recounts events following the 9/11 Attacks on the Towers and the Pentagon from the moment of the “jetliner slamming into the North Tower of the World Trade Center” to the one-year anniversary ceremonies at the Pentagon; in Shanksville, Pennsylvania; and at Ground Zero. It also covers the fighting of U.S. troops in Afghanistan and the capture and interrogation of prisoners from an al-Qaeda hideout in Pakistan.

The drawings allow readers to bear witness to the heroism of the first responders, firefighters, and police as they move from rescue to recovery over the ten months following the attacks and learn the stories of some of the survivors they saved. It is the story of the nameless “strangers [who] help[ed] one another, carrying the injured, offering water to the thirsty, and comforting the weeping.” (23)

We learn and view details that we may have not known, such as “Bullets start to fly when the flames and heat set off ammunition from fallen police officers’ firearms,” (11) the “Pentagon workers [who] plunge[d] into the smoke-filled building to restore water pressure made feeble by pipes broken in the attack,” (36) and former military who donned their old uniforms and “bluff[ed their way] past the roadblocks” to “sneak onto the Pile” to help. (50, 52)

For more mature readers, this book adds to the story of 9/11 in a more “graphic” way, and would supplement the novels, memoirs, and picture books to commemorate September 11th reviewed in my YA Wednesday guest blog "Novels, Memoirs, Graphics, and Picture Books to Commemorate 9/11."

----------

New Kid by Jerry Craft

Jordan leaves his neighborhood each day to attend seventh grade at Riverdale Academy Day School (although he would rather go to an art school) which is not as diverse as he would like and he is not sure he will fit in. In fact he is beginning to not fit in with his neighborhood friends, who start calling him “Private School.”

As one of the new kids at school, he has a guide, Liam, who is white, lives in a mansion, wears salmon shirts, is a third-generation RAD student—the auditorium isnamed after his family, and constantly says, “Just don’t judge me.” As Jordan becomes friends with Liam and some of the other kids, he realizes that everyone—teachers and students alike—judges each other, expecting them to fit stereotypes—Alexandra, the Weird Girl; Ashley, the Gossip Girl; Drew, the Troublemaker; Andy, the Bully; Ramon, the Mexican (who is actually Nicaraguan). Even Jordan feels his art teacher is not a real artist because she paints abstract art until she explains “I choose to do it to free up my creativity…to break boundaries. (222)

Jordan is shocked when Liam admits, “I just don’t feel like there’s anyone who’s like me at this school. I always feel so different.” And then continues, “Well, it’s better now. You and Drew are regular people.” (151) As the school year ends, Jordan admits to his parents, “You know, I feel kinda like a new kid.” (245)

A graphic novel that will appeal to readers grades 5-9, the drawings add nuance to the story. And the reader gains another entry into Jordan’s life and thoughts through his black/white sketch book.

----------

Jordan leaves his neighborhood each day to attend seventh grade at Riverdale Academy Day School (although he would rather go to an art school) which is not as diverse as he would like and he is not sure he will fit in. In fact he is beginning to not fit in with his neighborhood friends, who start calling him “Private School.”

As one of the new kids at school, he has a guide, Liam, who is white, lives in a mansion, wears salmon shirts, is a third-generation RAD student—the auditorium isnamed after his family, and constantly says, “Just don’t judge me.” As Jordan becomes friends with Liam and some of the other kids, he realizes that everyone—teachers and students alike—judges each other, expecting them to fit stereotypes—Alexandra, the Weird Girl; Ashley, the Gossip Girl; Drew, the Troublemaker; Andy, the Bully; Ramon, the Mexican (who is actually Nicaraguan). Even Jordan feels his art teacher is not a real artist because she paints abstract art until she explains “I choose to do it to free up my creativity…to break boundaries. (222)

Jordan is shocked when Liam admits, “I just don’t feel like there’s anyone who’s like me at this school. I always feel so different.” And then continues, “Well, it’s better now. You and Drew are regular people.” (151) As the school year ends, Jordan admits to his parents, “You know, I feel kinda like a new kid.” (245)

A graphic novel that will appeal to readers grades 5-9, the drawings add nuance to the story. And the reader gains another entry into Jordan’s life and thoughts through his black/white sketch book.

----------

Play Like a Girl (memoir) by Misty Wilson; illustrated by husband David Wilson

Even though friends were kind of confusing, at least football ALWAYS made sense.

Misty, a super-competitive athletic, was always challenging the boys in feats of strength and endurance. But, in the summer before seventh grade, she was surprised, when deciding to play for the town’s football league, that even her friends on the team did not support her decision. When Cole said, “‘Football really isn’t a sport for girls’…not a single one of them was sticking up for me.” (7)

Undeterred, Misty joins the team and talks her best friend Bree into joining also. But Bree quits and starts hanging around with the popular Mean Girl Ava, and when Misty tries to change to be more “girly” like the two (a hilarious try at makeup), they still make fun of her, and Misty realizes, with Bree gone, she has no friends.

She throws herself into football and, as she wins over many of her male team members, she is befriended by two of the cheerleaders who appear to accept her, and like her, just as she is. “Middle school was complicated. But I knew one thing for sure: I was done trying to be someone else.” (258)

Misty Wilson’s graphic memoir shares her story of football, family, middle-grade friends and frenenemies—and empowerment and identity.

This novel would be a choice in Sports Novels Book Clubs as well as Graphic Novels Book Clubs.

----------

Even though friends were kind of confusing, at least football ALWAYS made sense.

Misty, a super-competitive athletic, was always challenging the boys in feats of strength and endurance. But, in the summer before seventh grade, she was surprised, when deciding to play for the town’s football league, that even her friends on the team did not support her decision. When Cole said, “‘Football really isn’t a sport for girls’…not a single one of them was sticking up for me.” (7)

Undeterred, Misty joins the team and talks her best friend Bree into joining also. But Bree quits and starts hanging around with the popular Mean Girl Ava, and when Misty tries to change to be more “girly” like the two (a hilarious try at makeup), they still make fun of her, and Misty realizes, with Bree gone, she has no friends.

She throws herself into football and, as she wins over many of her male team members, she is befriended by two of the cheerleaders who appear to accept her, and like her, just as she is. “Middle school was complicated. But I knew one thing for sure: I was done trying to be someone else.” (258)

Misty Wilson’s graphic memoir shares her story of football, family, middle-grade friends and frenenemies—and empowerment and identity.

This novel would be a choice in Sports Novels Book Clubs as well as Graphic Novels Book Clubs.

----------

Swim Team by Johnnie Christmas

“But…Black people aren’t good at swimming.” (78)

When Bree and her father move from Brooklyn to Florida, she is excited about her first day of school. She has already made a friend, another 7th grader who lives in her apartment complex. Excited about joining the Math Team, Bree finds that the only elective that is still open is Swimming. And even though she tries to think about the things that make her happy—doing homework with her Dad, cooking, reading, and math—frequently “negative thoughts take over. And I think about the things that make me nervous and scared. I second-guess and doubt myself, even when I don’t want to.” (7) And some of the things that Bree doesn’t like are sports, pools, and she worries about not having friends. She is especially worried about Swimming class because she has never learned to swim.

Bree eludes the class, and, when she can no longer avoid it, Ms Etta, her neighbor and a former professional swimmer who happens to have swum on the team at Bree’s middle school back when the team almost won the championship, teaches Bree to swim. Ms Etta also explains the reasons that Bree assumes that Black people aren’t good at swimming. “From ancient Africa to modern Africa, from Chicago to Peru, in seas, rivers, lakes and pools, Black people have always swum and always will.” (80-81) But she also explains the history of segregation and discrimination that limited Blacks’ access to pools, Telling about Eugene Williams’ murder (1919), David Isom’s breaking of the color line (1958), and John Lewis’ protest (1962).

Bree becomes quite a good swimmer, and the coach of the school swim team tricks her into trying out. She joins the team with her new best friend Clara, and, with the help of Ms. Etta, the team makes it to the championship. But when a student, Mean-Girl Keisha, transfers from the rival private school and joins the team and the girls find out that Clara has won a swimming scholarship to the same private school for the next year, the team relay threatens to fall apart.

That is when they learn what happened to Ms. Etta’s team years ago that cost them the championship. Reuniting the former Swim Sisters reunites the present team as they learn about relationships. “A team is like a family. Sometimes family shows you how to do a flip turn. Or tells funny jokes—And is a little annoying. (215)

Johnnie Christmas’ new graphic novel tells the story of middle-grade friendships, socioeconomic prejudice and racial discrimination, and swimming through those negative thoughts that hold us back. In the classroom this novel could lead to some research on Black athletes in sports through history and discrimination.

Swim Team would be a choice in Sports Novels Book Clubs as well as Graphic Novels Book Clubs.

----------

“But…Black people aren’t good at swimming.” (78)

When Bree and her father move from Brooklyn to Florida, she is excited about her first day of school. She has already made a friend, another 7th grader who lives in her apartment complex. Excited about joining the Math Team, Bree finds that the only elective that is still open is Swimming. And even though she tries to think about the things that make her happy—doing homework with her Dad, cooking, reading, and math—frequently “negative thoughts take over. And I think about the things that make me nervous and scared. I second-guess and doubt myself, even when I don’t want to.” (7) And some of the things that Bree doesn’t like are sports, pools, and she worries about not having friends. She is especially worried about Swimming class because she has never learned to swim.

Bree eludes the class, and, when she can no longer avoid it, Ms Etta, her neighbor and a former professional swimmer who happens to have swum on the team at Bree’s middle school back when the team almost won the championship, teaches Bree to swim. Ms Etta also explains the reasons that Bree assumes that Black people aren’t good at swimming. “From ancient Africa to modern Africa, from Chicago to Peru, in seas, rivers, lakes and pools, Black people have always swum and always will.” (80-81) But she also explains the history of segregation and discrimination that limited Blacks’ access to pools, Telling about Eugene Williams’ murder (1919), David Isom’s breaking of the color line (1958), and John Lewis’ protest (1962).

Bree becomes quite a good swimmer, and the coach of the school swim team tricks her into trying out. She joins the team with her new best friend Clara, and, with the help of Ms. Etta, the team makes it to the championship. But when a student, Mean-Girl Keisha, transfers from the rival private school and joins the team and the girls find out that Clara has won a swimming scholarship to the same private school for the next year, the team relay threatens to fall apart.

That is when they learn what happened to Ms. Etta’s team years ago that cost them the championship. Reuniting the former Swim Sisters reunites the present team as they learn about relationships. “A team is like a family. Sometimes family shows you how to do a flip turn. Or tells funny jokes—And is a little annoying. (215)

Johnnie Christmas’ new graphic novel tells the story of middle-grade friendships, socioeconomic prejudice and racial discrimination, and swimming through those negative thoughts that hold us back. In the classroom this novel could lead to some research on Black athletes in sports through history and discrimination.

Swim Team would be a choice in Sports Novels Book Clubs as well as Graphic Novels Book Clubs.

----------

Sylvie (memoir) by Sylvie Kantorovitz

Christine: “I hate being different!”

Sylvie [thinking]: “Her too?”

Christine: “But really, we are ALL different! In one way or another. And some differences come from US! Like how you love to draw!” (177)

In Sylvie Kantorovitz’s graphic memoir, readers literally watch Sylvie grow up through the author’s own illustrations. The memoir begins in France where Sylvie, her brother, and her parents live in the school where her father is principal and continues through the birth of two more siblings and later a move during high school to Lyon.

Sylvie has many worries in common with many of her readers. She doesn’t want to be different. She was born in Morocco, so some of her classmates say she is not “French.” “Oh, how I wish I was born in France like all the others!” (73) She and her younger brother Alibert are the only Jewish children in their school. “Whenever possible I let people assume I was like them.” ((74)

Sylvie also has a complicated family life. Her parents are always fighting. While she father is kind and supportive, her mother is very hard on her. “[An A] doesn’t count if the others also got As.” (6) Her mother’s values are very different from Sylvie’s. “Being ‘feminine’ was important to Mom. It didn’t feel that important to me.” (110-111) Her mother always seems to be angry, and when Alibert does not do well in school, he is sent away to a boarding school. Sylvie just doesn’t understand her mother. “Could Alibert be right? Could someone actually LIKE being angry?” (135) “Was I allowed to feel so conflicted about my own mother? Could I feel shame and anger and still love her?” (131)

In school when the teacher asks the students if anyone knows what they want to be when they grow up, to Sylvie’s surprise, everyone else does. “I was the only one without a plan for the future. Was something wrong with me?” (38)

In her last year of high school Sylvie has a boyfriend, Pierre, and hearing about his family’s troubles—his mother is depressed and sometimes stays in bed all day, “I wondered if every family had an ongoing drama, hidden from the outside world.” (239) Maybe her family is not so different.

Through it all from a young age, Sylvie realizes that “drawing was what I really loved to do.” (10) but because of her mother’s disdain, she didn’t see it as a profession. Finally, with her father’s support and the courage to confront her mother, Sylvie has come up with a long-term plan for independence.

A memoir is an account of one's personal life and experiences built on the memory of the writer and formed by the present reflection on the past. This memoir is enhanced by its visual quality.

But what I would find most important to adolescent readers is the realization that while we all are different, at the same time we are all very much alike.

----------

Christine: “I hate being different!”

Sylvie [thinking]: “Her too?”

Christine: “But really, we are ALL different! In one way or another. And some differences come from US! Like how you love to draw!” (177)

In Sylvie Kantorovitz’s graphic memoir, readers literally watch Sylvie grow up through the author’s own illustrations. The memoir begins in France where Sylvie, her brother, and her parents live in the school where her father is principal and continues through the birth of two more siblings and later a move during high school to Lyon.

Sylvie has many worries in common with many of her readers. She doesn’t want to be different. She was born in Morocco, so some of her classmates say she is not “French.” “Oh, how I wish I was born in France like all the others!” (73) She and her younger brother Alibert are the only Jewish children in their school. “Whenever possible I let people assume I was like them.” ((74)

Sylvie also has a complicated family life. Her parents are always fighting. While she father is kind and supportive, her mother is very hard on her. “[An A] doesn’t count if the others also got As.” (6) Her mother’s values are very different from Sylvie’s. “Being ‘feminine’ was important to Mom. It didn’t feel that important to me.” (110-111) Her mother always seems to be angry, and when Alibert does not do well in school, he is sent away to a boarding school. Sylvie just doesn’t understand her mother. “Could Alibert be right? Could someone actually LIKE being angry?” (135) “Was I allowed to feel so conflicted about my own mother? Could I feel shame and anger and still love her?” (131)

In school when the teacher asks the students if anyone knows what they want to be when they grow up, to Sylvie’s surprise, everyone else does. “I was the only one without a plan for the future. Was something wrong with me?” (38)

In her last year of high school Sylvie has a boyfriend, Pierre, and hearing about his family’s troubles—his mother is depressed and sometimes stays in bed all day, “I wondered if every family had an ongoing drama, hidden from the outside world.” (239) Maybe her family is not so different.

Through it all from a young age, Sylvie realizes that “drawing was what I really loved to do.” (10) but because of her mother’s disdain, she didn’t see it as a profession. Finally, with her father’s support and the courage to confront her mother, Sylvie has come up with a long-term plan for independence.

A memoir is an account of one's personal life and experiences built on the memory of the writer and formed by the present reflection on the past. This memoir is enhanced by its visual quality.

But what I would find most important to adolescent readers is the realization that while we all are different, at the same time we are all very much alike.

----------

Twins by Varian Johnson; illustrated by Shannon Wright

“Many twins struggle to cultivate their own identities while being so similar to one another. And that struggle lasts a lifetime” (Smithsonian Magazine, Jan 24, 2014)) While most people can take solace in the fact that they are unique and one of a kind, twins do not have that. Because twin DNA is practically identical when they are born, each must take on a journey of self-discovery to forge their own identity, which is different than those who are not twins. (Scientific America, March 15, 2011)

Maureen and Francine Carter are identical twins, but, as they enter middle school, differences emerge. Fran is more outgoing (“the “talker”); Maureen is a better academic student (“the “thinker”). Francine (“Fran”) is more open to the idea of forming their own identities, even requesting that they be placed in different classes and choose different clubs. Maureen is more resistant and, thinking it was a scheduling mistake, tries to get their classes changed. Both feel like they live in the other’s shadow.

Even at the beginning of the year, Fran declares her intention to run for President of Student Council. Trying to raise her grade (which may be her only non-A) in Cadet Corps, Maureen also runs for the position, and “the battle lines are drawn.” The twins even move into separate bedrooms. Some friends refuse to take sides; some who were drafted by Fran before Maureen’s announcement work with Fran’s campaign, and Maureen is forced to make new friends, which she does, improving her self-confidence.

As they move from battling to supporting each other, they both find their own identities and ways to balance their differences while celebrating their similarities.

Told through dialogue, pictures, and blocks of Maureen’s narration, the graphic novel will serve as a mirror, not just to readers who are twins, but all those navigating the changes that occur in middle school.

----------

“Many twins struggle to cultivate their own identities while being so similar to one another. And that struggle lasts a lifetime” (Smithsonian Magazine, Jan 24, 2014)) While most people can take solace in the fact that they are unique and one of a kind, twins do not have that. Because twin DNA is practically identical when they are born, each must take on a journey of self-discovery to forge their own identity, which is different than those who are not twins. (Scientific America, March 15, 2011)

Maureen and Francine Carter are identical twins, but, as they enter middle school, differences emerge. Fran is more outgoing (“the “talker”); Maureen is a better academic student (“the “thinker”). Francine (“Fran”) is more open to the idea of forming their own identities, even requesting that they be placed in different classes and choose different clubs. Maureen is more resistant and, thinking it was a scheduling mistake, tries to get their classes changed. Both feel like they live in the other’s shadow.

Even at the beginning of the year, Fran declares her intention to run for President of Student Council. Trying to raise her grade (which may be her only non-A) in Cadet Corps, Maureen also runs for the position, and “the battle lines are drawn.” The twins even move into separate bedrooms. Some friends refuse to take sides; some who were drafted by Fran before Maureen’s announcement work with Fran’s campaign, and Maureen is forced to make new friends, which she does, improving her self-confidence.

As they move from battling to supporting each other, they both find their own identities and ways to balance their differences while celebrating their similarities.

Told through dialogue, pictures, and blocks of Maureen’s narration, the graphic novel will serve as a mirror, not just to readers who are twins, but all those navigating the changes that occur in middle school.

----------

When Stars Are Scattered by Victoria Jamieson and Omar Mohamed

“No one chooses to be a refugee. To leave their homes, family, and country.” (Omar Mohamed’s Author’s Note) At least 79.5 million people around the world have been forced to flee their homes. Among them are nearly 26 million refugees, half of whom are under the age of 18. (UNHCR.org)

Omar and his younger brother Hassan spent 15 years in Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya, leaving their home in Somalia when Omar was 4 years old. Their father had been killed and mother left, not returning before the villagers were compelled to flee the violence, taking the boys with them. This is Omar and Hassan’s story, beginning after 7 years living in the camp with Fatuma, their appointed foster mother, also a refugee.

It is the story of Omar who was encouraged to begin school at age ten and found hope in education. Though it was challenging to take care of Hassan, chores, and studying, he earned his way into middle school and then high school.

It is the story of his brother Hassan who had seizures and did not speak but was kind to children and animals and watched over by the camp community.

It is the story of the girls of the camp, especially Nimo and Maryam, and the restrictions and expectations placed on girls by their society.

It is the story of the camp refugees and constant hunger, deprivation, and despair but also the joyful celebrations of holidays and traditions and the hope for reunification with family and resettlement in a safe country. And dreams.

“None of us ask to be born where we are, or how we are. The challenge of life is to make the most out of what you’ve been given. And despite all the things I don’t have…I have been given something very important. The love of others is a gift from God, and it shouldn’t be taken for granted.” (212)

Omar’s story, co-written and illustrated by Victoria Jamieson, is a graphic memoir that comes alive through the drawings. It includes an Afterword that takes readers from the story’s ending in 2009 to Omar and Hassan’s life today. This novel will be an important introduction to many readers to a life their peers may have experienced. Hopefully it is a story which will lead to understanding, compassion, and respect. As Omar’s middle school English teacher tells them, “Throughout your life, people may shout ugly words at you like, ‘Go home, refugee!’ or ‘You have no right to be here!’ When you meet these people, tell them to look at the stars, and how they move across the sky. No one tells a star to go home.” (120)

----------

“No one chooses to be a refugee. To leave their homes, family, and country.” (Omar Mohamed’s Author’s Note) At least 79.5 million people around the world have been forced to flee their homes. Among them are nearly 26 million refugees, half of whom are under the age of 18. (UNHCR.org)

Omar and his younger brother Hassan spent 15 years in Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya, leaving their home in Somalia when Omar was 4 years old. Their father had been killed and mother left, not returning before the villagers were compelled to flee the violence, taking the boys with them. This is Omar and Hassan’s story, beginning after 7 years living in the camp with Fatuma, their appointed foster mother, also a refugee.

It is the story of Omar who was encouraged to begin school at age ten and found hope in education. Though it was challenging to take care of Hassan, chores, and studying, he earned his way into middle school and then high school.

It is the story of his brother Hassan who had seizures and did not speak but was kind to children and animals and watched over by the camp community.

It is the story of the girls of the camp, especially Nimo and Maryam, and the restrictions and expectations placed on girls by their society.

It is the story of the camp refugees and constant hunger, deprivation, and despair but also the joyful celebrations of holidays and traditions and the hope for reunification with family and resettlement in a safe country. And dreams.

“None of us ask to be born where we are, or how we are. The challenge of life is to make the most out of what you’ve been given. And despite all the things I don’t have…I have been given something very important. The love of others is a gift from God, and it shouldn’t be taken for granted.” (212)

Omar’s story, co-written and illustrated by Victoria Jamieson, is a graphic memoir that comes alive through the drawings. It includes an Afterword that takes readers from the story’s ending in 2009 to Omar and Hassan’s life today. This novel will be an important introduction to many readers to a life their peers may have experienced. Hopefully it is a story which will lead to understanding, compassion, and respect. As Omar’s middle school English teacher tells them, “Throughout your life, people may shout ugly words at you like, ‘Go home, refugee!’ or ‘You have no right to be here!’ When you meet these people, tell them to look at the stars, and how they move across the sky. No one tells a star to go home.” (120)

----------

Wonder Woman: Tempest Tossed by Laurie Halse Anderson;

illustrated by Leila del Duca

Wonder Woman is the most popular female comic-book superhero of all time. In 1941 she emerged, the creation of lawyer-psychologist-professor William Marston, fully formed as an adult to chronicle the growth in the power of women. Readers of DC comics knew her as Princess Diana of Themyscira but how did she become the symbol of truth, justice and equality.

Author Laurie Halse Anderson, somewhat of a Wonder Woman herself, a woman of strength, compassion, and empathy, approachable and full of warmth, speaking truths and working for justice, was the perfect person to bring Wonder Woman to life. In Tempest Tossed she teamed with artist Leila del Duca to fill in the adolescent years of Diana, tossed from her homeland on her 16th birthday as she tries to save refugees, becoming a refugee herself exiled in America. In her new homeland, she finds danger and injustice and joins those who fight to make a difference.

Again, author Laurie Halse Anderson shows the strength of women but most of all the power adolescents can wield when they find their purpose.

----------

illustrated by Leila del Duca

Wonder Woman is the most popular female comic-book superhero of all time. In 1941 she emerged, the creation of lawyer-psychologist-professor William Marston, fully formed as an adult to chronicle the growth in the power of women. Readers of DC comics knew her as Princess Diana of Themyscira but how did she become the symbol of truth, justice and equality.

Author Laurie Halse Anderson, somewhat of a Wonder Woman herself, a woman of strength, compassion, and empathy, approachable and full of warmth, speaking truths and working for justice, was the perfect person to bring Wonder Woman to life. In Tempest Tossed she teamed with artist Leila del Duca to fill in the adolescent years of Diana, tossed from her homeland on her 16th birthday as she tries to save refugees, becoming a refugee herself exiled in America. In her new homeland, she finds danger and injustice and joins those who fight to make a difference.

Again, author Laurie Halse Anderson shows the strength of women but most of all the power adolescents can wield when they find their purpose.

----------

Yummy: The Last Days of a Southside Shorty by G. Neri; illustrated by Randy DeBurke

In August of 1994, 11-year-old Robert “Yummy” Sandifer fired a gun at a group of rival gang members, accidentally killing a neighborhood girl, Shavon Dean. He was then killed by 14 and 16-year-old brother, member of his own gang Chicago’s Black Disciples. This is the true story of his last days from the perspective of a fictitious 11-year-old neighbor boy Roger.

Dramatically illustrated in black and white (which gives readers a lot to discuss), this quick read appeals to many readers, especially those from neighborhoods of violence. I was introduced to this short text by a teacher who had distributed it to a class of "reluctant" male readers in an alternative school program. She told me that at the end of the period, she had to pry the books from their hands for them to finish reading in the next classes.

In August of 1994, 11-year-old Robert “Yummy” Sandifer fired a gun at a group of rival gang members, accidentally killing a neighborhood girl, Shavon Dean. He was then killed by 14 and 16-year-old brother, member of his own gang Chicago’s Black Disciples. This is the true story of his last days from the perspective of a fictitious 11-year-old neighbor boy Roger.

Dramatically illustrated in black and white (which gives readers a lot to discuss), this quick read appeals to many readers, especially those from neighborhoods of violence. I was introduced to this short text by a teacher who had distributed it to a class of "reluctant" male readers in an alternative school program. She told me that at the end of the period, she had to pry the books from their hands for them to finish reading in the next classes.

Research opportunities:

1) After reading, my Adolescent Literature college students then decided to research the crime(s) and what happened to the Hardaway brothers. In 1994 this was the the cover story of Time magazine.

2) The efficacy of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, signed into law a few days after Yummy's death, as well as other social justice issues, can provide a debate topic.

----------

1) After reading, my Adolescent Literature college students then decided to research the crime(s) and what happened to the Hardaway brothers. In 1994 this was the the cover story of Time magazine.

2) The efficacy of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, signed into law a few days after Yummy's death, as well as other social justice issues, can provide a debate topic.

----------

√See Talking Texts: A Teachers' Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum for ideas to incorporate Graphic Novel Book Clubs in the curriculum.

Proudly powered by Weebly