- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

- Asian, Asian-American

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

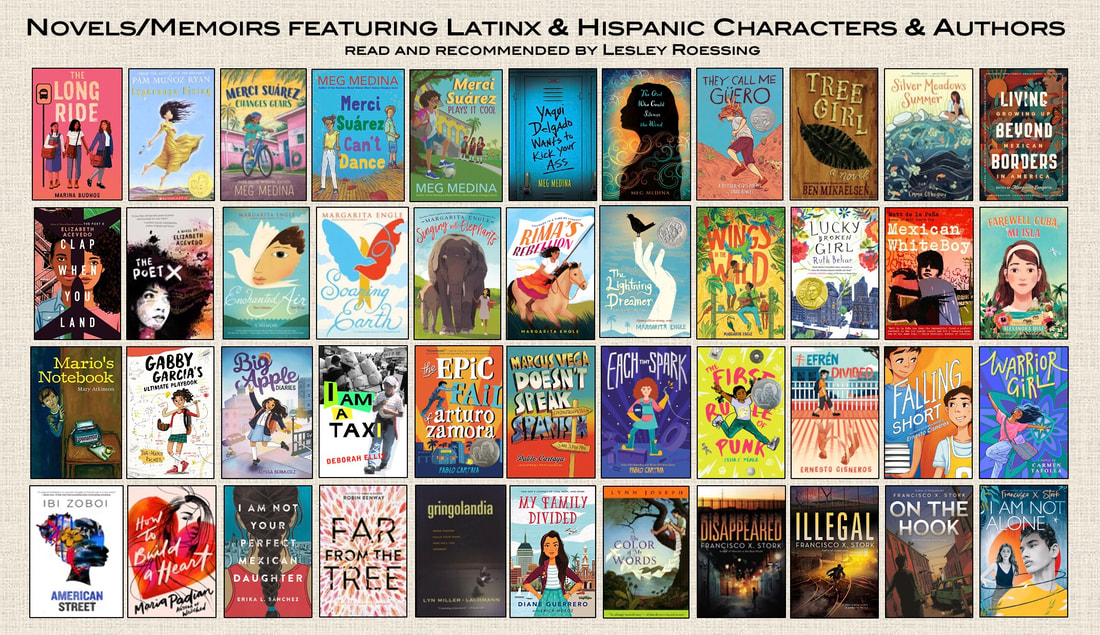

Readings for National Hispanic Heritage Month and the Rest of the Year

The Long Ride; Esperanza Rising; Merci Suarez Changes Gears; Merci Suarez Can’t Dance; Merci Suarez Plays It Cool; Yaqui Delgado Wants to Kick Your Ass; The Girl Who Could Silence the Wind; They Call Me Gero; Tree Girl; Silver Meadows Summer; Living Beyond Borders; Clap When You Land; The Poet X; Enchanted Air; Soaring Earth; Singing with Elephants; Rima’s Rebellion; The Lightning Dreamer; Wings in the Wild; Lucky Broken Girl; Mexican White Boy; Farewell Cuba, Mi Isla; Mario’s Notebook; Gabby Garcia’s Ultimate Playbook; Big Apple Diaries (memoir); I Am a Taxi; The Epic Fail of Arturo Zamora; Marcus Vega Doesn’t Speak Spanish; Each Tiny Spark; The First Rule of Punk; Efren Divided; Falling Short; Warrior Girl; American Street; How to Build a Heart; I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter; Far from the Tree; Gringolandia; My Divided Family (memoir); The Color of My Words; Disappeared; Illegal; On the Hook; I Am Not Alone

These are novels I have read and can recommend for Upper Elementary, Middle Grade, and High School readers— 44 novels and memoirs in a range of reading levels with a diversity of Hispanic and Latinx characters and settings, written and formatted in prose, verse, and graphics by a variety of authors, many of whom are of Hispanic/Latinx heritage.

Here I review 23 of my more-recently read.

----------

Big Apple Diaries by Alyssa Bermudez (memoir)

Big Apple Diaries is based on the author’s actual journals which she has illustrated as a graphic diary memoir encompassing the time from September 2000 to June 2002.

Alyssa Bermudez was the child of divorced parents, dividing her time between her Puerto Rican father who lived in Manhattan and her Italian-British mother who lived in Queens. This diary begins in 7th grade where “It seems that suddenly every grade you get and everything you do matters…. Now our friends are obsessed with who has a crush on who. And who is the coolest. There is all of this pressure to be popular and smart or face a dim future being a weirdo with no job.” (10)

Alyssa is not particularly popular, but not particularly unpopular either, has a much older half-brother and two best friends, Lucy and Carmen, and is an artist who wants to become a shoe designer. In this 7th grade year, she experiences her first crush—Alejandro from Columbia. Her diary takes us through the typical middle school year familiar to most of our adolescent readers. “Yesterday I did something very stupid. I knew it was stupid at the time and I still did it anyway. It’s like the drive to be popular makes me see things through stupid lenses.” (83) Typical preteen, she does many “stupid things”: shave her eyebrows, accidently dye her hair orange, cut school.

Two months before her thirteenth birthday, the attacks of September 11th occur. Alyssa’s mother worked in a building that faced the Twin Towers. She escaped and caught the last train to Queens. Her father did work in the World Trade Center but was meeting a client in Jersey City that morning (and bought skates to skate the 19.5 miles back to his Manhattan home). Overcome with emotion, Alyssa writes no entries for that day and the following few.

After that time Alyssa recognizes, “I sort of feel like I have no control over anything. I want to come back to the normal life I knew and the Twin Towers that I visited with Dad all the time.”(195) She finds herself changing, maturing: “When things can change in an instant, it’s hard to accept it. I want to make the right decisions and prove my worth. I want to be brave.” (211)

On her thirteenth birthday she begins to wonder “Who am I?” and begins thinking about her character and how she may want to change. Her diary takes the reader through graduation to a future where “Some things I’ll take with me and other things I will leave behind.” (274)

Big Apple Diaries, a graphic memoir of an NYC adolescent who experienced 9/11 as part of her middle grade years adds yet another perspective or dimension to other novels written about 9/11.

----------

Clap When You Land by Elizabeth Acevedo

One plane crash. One father’s death. Two families’ loss.

“Papi boards the same flight every year.” (18) This year when her father leaves for his annual 3 months in his homeland, his daughter Yahaira knows the secret he has kept for 17 years. But she is unaware of who else knows. Not Camino, the other daughter who is practically Yahaira’s twin. Camino only knows she has a Papi who lives and works in New York City nine months a year to support her and the aunt who has raised her since her mother died.

When Papi’s plane crashes on its way from New York to the Dominican Republic, all passengers lose their lives and many families are left grieving. But none are more affected than the two daughters who loved their Papi, the two daughters whose mothers he had married.

“It was like he was two

Completely different men.

It’s like he split himself in half.

It’s like he bridged himself across the Atlantic.

Never fully here or there.

One toe in each country.” (360)

Sixteen year old Yahaira lives in NYC, a high school chess champion until she discovered her father’s secret second marriage certificate and stopped speaking to him and stopped competing, and has a girlfriend who is an environmentalist and a deep sense of what’s right. “This girl felt about me/how I felt about her.” (77)

Growing up in NYC, Yahaira was raised Dominican.

“If you asked me what I was,

& you meant in terms of culture,

I’d say Dominican.

No hesitation,

no question about it.

Can you be from a place

you have never been? “ (97)

Sixteen year old Camino’s mother died quite suddenly when she was young, and she and her aunt, the community spiritual healer, are dependent on the money her father sends. Not wealthy by any means, they are the considered well-off in the barrio where Papi was raised; Camino goes to a private school and her father pays the local sex trafficker to leave her alone.

And then the plane crash occurs.

“Two months to seventeen, two dead parents,

& an aunt who looks worried

Because we both know, without my father,

Without his help, life as we’ve known it has ended.” (105)

Camino’s goal has always been to move to New York, live with her father, and study to become a doctor at Columbia University. Finding out about her father’s family in New York, she makes a plan with her share of the insurance money from the airlines. But Yahaira has her own plan—to go to her father’s Dominican burial despite the wishes of her mother, meet this sister, and explore her culture.

When they all show up, readers see just how powerfully a family can form.

“my sister

grasps my hand

I feel her squeeze

& do not let go

hold tight.” (353)

“It is awkward, these familial ties

& breaks we share.” (405)

After the crash of American Airlines Flight 587 just two months after 9/11/2001, it was sometimes a spontaneous reaction for passengers to clap when the plane landed, one of “the many ways Dominicans celebrate touching down onto our island.” (Author’s Note).

----------

Disappeared and Illegal by Francisco Stork

Francisco’s Stork’s novel Disappeared takes place in Juarez, Mexico, and depicts sex trafficking, the cartel, murder, poverty, betrayal, abandonment.

Sara Zapata, a young reporter for a local paper, is committed to finding and saving the young women she learns are being kidnapped, including her best friend Linda, despite the warnings of her boss and the threats to herself and her family.

Sara’s younger brother Emiliano, whose life has been affected by his father’s abandonment—of the family and his native Mexico—is looking for a better life, for ways to make money to pay the family bills and win the love of his wealthy girlfriend.

The siblings find in following their consciences, helping others, and making moral choices, they need to do what is right—not what is easy or even safe, and must sacrifice, or revise, their personal goals. To save their lives, Sara and Emiliano escape to the United States to find a better life and to bring the cartel who is trafficking the women to justice. They cross the border and are attacked in the dessert.

Sara turns herself over to the authorities, certain that she meets the requirements for asylum but, as her time in the detention facility grows longer and she observes women being mistreated and deported for no reason, she questions her assumptions. “I imagined that all I had to do was show the authorities the evidence of actual persecution, of actual threats, such as people machine-gunning our house in Juarez.… I saw my case as fitting within the legal reasons for asylum under the law of the United States. Was I wrong about the United States?” (31) She finds, “The whole process of who gets asylum and who gets detained, who gets a bond and who gets released, who gets a visa and who gets deported. I mean, it’s not as rational as I imagined it would be.” (34)

Meanwhile Emiliano enters the country illegally and goes to Chicago with his father, planning to turn Linda’s evidence against the cartel over to the proper authorities. He also finds America to be less than welcoming. As he tells his new friend Aniela, “I think that in Mexico I feel like I belong all the time. I never feel not wanted like I do here sometimes. Here I’m always looking over my shoulder even when no one is there.…knowing that you belong and are wanted is major.” (251)

When Sara’s attorney is killed and she is placed in solitary confinement and Emiliano finds he can no longer trust his father, tensions escalate. A study of government corruption and the asylum process, this sequel to Disappeared is a thriller that will hook the most reluctant adolescent reader. Enough background is given in Illegal that it may not be completely necessary to read Disappeared first but it would surely enhance the reading.

----------

Falling Short by Ernesto Cisneros

“I’m not sure everyone has a best friend like I do. No, not the average “bestie” you pretty much only see and talk to at school. I’m talking best friends who know you inside and out. Friends you feel comfortable enough to cry or change in front of, friends so close that they feel more like a brother or sister.

That’s what I’ve got in Isaac.

And I would do anything for him. Just like he’d do for me.” (180)

Sixth graders Isaac and Marco are best friends not only because they are very, very good friends but because they each want the best for the other. Isaac is athletically gifted and a star of the basketball team but has problems with school work; Marco is academically gifted but wants to become an athlete to win the approval of his father who left home for a new girlfriend and her son. Isaac’s father also left home but because his drinking problem has gotten the best of him. “Drinking had pretty much become more important than either Ama or me.” (92)

When the very short Marco learns of 5’3” NBA player Muggsy Bogues, he decides to try out for the school basketball team and, with the determination he applies to everything, studies YouTube videos and practices nonstop. Isaac becomes his coach and even figures out how he can change his plays to help Marco be successful. “That’s probably the one thing that separates [Isaac] from every other kid I’ve ever met. He never judges me. Never makes me feel stupid.” (154) And when Isaac helps Marco with his schoolwork (in a strange turn of events), he learns that he is smarter than he thought.

Told in alternating narratives by Isaac and Marco, this is a story of true friendship, broken families, bullying, sports (I learned a lot of basketball terms!), teamwork and collaboration, featuring Latinx and Jewish characters. It is story of what is takes to not fall short.

----------

Far from the Tree by Robin Benway

Melissa Taylor was their mother. That is what Grace. Maya, and Joaquin have in common. But it is enough to make them "family" when they meet as teenagers. All three were given up at birth or shortly thereafter: Grace to a loving middle-class family; Maya to a wealthy family who then had their own biological child—and their own problems; and Joaquin to a lifetime of foster homes.

Then 16-year-old Grace has her own baby, and, after her child Milly is adopted, Grace yearns to finds her biological mother.

When the three siblings meet, they immediately bond and help each other, not only find the part of their identity they thought missing, but they help each other fit into their present families and lives and discover that it is possible to have two families and feel complete. Maya is able to accept her place as the only brunette in a family of tall redheads and forgive a mother who is an alcoholic; Joaquin is ready to value himself and trust enough to let himself be adopted; and Grace can forgive herself for giving her baby a life apart from her.

These are characters who get under your skin as soon as you meet them.

Far from the Tree won the 2017 National Book Award for Young People's Literature.

----------

Farewell Cuba, Mi Isla by Alexandra Diaz

“Look outside your window, children,” Mami said as they took their seats. “You may never see your country again.” (ARC, 36)

Victoria had a wonderful life in Cuba where she lived with her mother, father, and younger sister and brother. Also in the same duplex lived her cousin Jackie, her aunt, her uncle, and her baby cousin/godson. Even though they were very different and attended different schools in Havana, 12-year-old Victoria and Jackie were best friends, and they both spent time at their Papalfonso and Mamlara’s finca where Victoria rode her horse and swam with her cousin, a ranch that Victoria would inherit.

October 1960: With Fidel Castro in power and protestors arrested, news restricted, and professionals prohibited from leaving the country, Victoria’s family makes the decision to go to Miami, expecting their exile to “only last a few weeks, until the U.S. presidential election.” (14)

Alternating chapters focus on Victoria and Jackie and permit readers to learn what is happening in Cuba and about the Cuban community in Miami. Here Victoria lives in poverty (her father’s engineering degree of no use as he labors for minimum wage), and she tries to take charge of feeding her family. When Jackie arrives in Miami through the Peter Pan Project (reminiscent of the Holocaust Kindertransport), readers see how being apart from her immediate family affects her and her relationship with Victoria.

I often have read and reviewed novels (and memoirs) by Margarita Engle and noted that I learned quite a lot of Cuban history, a history missing from my education. Diaz’s novel, inspired by the experiences of her mother and family who came to the

United States from Cuba in 1960, spans October 1960 to June 1961 and teaches readers even more about Castro and his effect on Cuba and the Cuban citizens and the role the U.S. government played. This novel should be included in every American history course. This is also a story of prejudice, as experienced by Katya, Victoria’s Russian school friend, and of resilience and family. The Author’s Note further expands on the historical facts and includes a glossary of Cuban terms.

----------

First Rule of Punk by Celia Perez

The first rule of punk is to “be yourself,” but that’s hard when your mom moves you a thousand miles from your home, friends, and father in Florida for two years in Chicago; when your SuperMexican Mom is always criticizing your Spanish, your clothes, and your vegetarianism; when the Mexican students in your new school call you a coconut—brown on the outside and white on the inside, and your new principal finds your talent not traditional enough to honor the man the school is named after.

Maria Luisa, or Malu, is the child of a divorced English professor mother and a record-store owner father. She makes zines, hates cilantro and spicy food, speaks mostly English, and loves punk. She feels “like Mom’s Maria Luisa and my Malu are two different people. The only thing we have in common is an accent over a vowel.”

She and her mother move to a Mexican neighborhood and middle school in Chicago, and Malu is not sure she will make friends (especially after meeting Mean Girl Selena), but she meets a group of outsiders and talks them into forming a punk rock band, the Co-Co’s. When their act is cut from performing at the school’s Fall Fiesta for not “fitting in,” Malu plans an Alterna-Fiesta talent show where they will perform and she will sing in Spanish a song that is “not your abuela’s music. “I looked over at Joe, Benny, and Ellie, who were blowing straw wrappers at each other. ‘My friends.’ I might have actually found my Yellow-Brick-Road posse.” (318)

Told through a mixture of prose and vines.

----------

How to Build a Heart by Maria Padian

According to the DODEA, “Children who experience the loss of a parent or other family member through a military line-of-duty death are likely to face a number of unique issues.” Izzy’s father died when she was ten, before her younger brother Jack was born. Her small family, estranged from her father’s relatives, has moved from place to place as her mother, a nurse’s aide, tries to support them.

When she moves to a a trailer park in Virginia, Isabella Crawford becomes embroiled in the family drama of her best friend, and, as a member of the acapella group at the private school where she is a scholarship student, she befriends a freshman who is battling her own demons. To make her life even more complicated, her family becomes the recipient of a Habit for Humanity house, and Izzy has to volunteer hours towards its construction.

In the midst of all this drama, Izzy, who is determined to keep her family’s circumstances a secret from her classmates, discovers what friendship and trusting friends—and family—really means as she reconnects with her father’s pig-farming family and finds that her wealthy friends and her new boyfriend care about her, not her economic status.

Izzy, an adolescent straddled between two cultures—that of her Puerto Rican mother and her North Carolina father—is not quite sure where she belongs but learns to share her world with others.

----------

I Am Not Alone by Francisco Stork

Usually when I finish a novel, my book is full of stickies marking quotes I want to use in my review. However, halfway through I Am Not Alone, I realized that I hadn’t marked any passages, too intent in following Alberto and Grace’s journeys to justice, maybe even salvation, and possibly each other—and solving a mystery.

Alberto is an undocumented teen immigrant from Mexico who lives with his sister and her baby. He works very hard to keep Lupe recovered from her drug addiction and tries to convince her to leave Wayne, her abusive boyfriend who is the married father of her baby, the owner of their apartment, and Alberto’s boss. He also has quit high school to work many hours to send most of his $7/hour paycheck to his mother and sisters in Mexico. Adding to his challenges, Alberto is struggling with the onset of schizophrenia and hears a voice in his head, which he refers to as “Captain America,” that prescribes his actions and constantly gives him critical thoughts about himself.

I first met Alberto and Captain America in Stork’s 2018 short story “Captain, My Captain” in Unbroken: Stories Starring Disabled Teens, a story limited to Alberto’s perspective.

In this novel, readers are also introduced to Grace, a high school senior. Grace is a high achiever and thinks she has her life plan figured out: boyfriend Michael, high school valedictorian, Princeton college, and then medical school to become a pyschiatrist like her father. Still reeling from her father leaving and her parents’ divorce, Alberto comes to clean her windows after a paint job, and Grace’s world falls apart as she begins to question her goals and even the meaning of love.

Readers also meet Grace’s supportive mother, her paternal grandfather and young cousin Benny, and Alberto’s house painting co-workers Jimbo and the drug-dealing Lucas.

Then the elderly resident of the apartment that Alberto, Jimbo, and Lucas were painting is murdered, and the evidence points to Alberto who is afraid that Captain America made him kill the woman. As Alberto looks for clues and Grace separately tries to prove his innocence, involving her grandfather, Benny, and their rabbi, and even the police detective, Alberto—and Grace—learn the meaning of friendship and community and believing in oneself and others.

This is an important novel about mental illness, the role religion can play, and unrestricted friendship for those teens who may just need this story to accept themselves or their peers. It also highlights the challenges faced by undocumented youth. Approximately 620,000 K-12 students in the United States are undocumented; more than half of K-12 undocumented students (54%) are from Central and South American countries, including Mexico (130,000), Honduras (50,000), Guatemala (40,000), and El Salvador (30,000).

For ideas to use “Captain, My Captain” in lessons to foster mental health literacy in the classroom, see Roessing, Lesley and Jessica Traylor. “Exploring Mental Health Literacy through Book Clubs.” Fostering Mental Health Literacy through Adolescent Literature, edited by Eisenbach, Brooke and Jason Scott Frydman, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2021.

----------

Living Beyond Borders: Stories about Growing Up Mexican in America by Margarita Longoria, ed.

As Mexican-Americans, we have always needed to defend who we are, where we were born, and prove to others that we are in fact Americans. (Editor’s Intro)

Twenty YA stories, essays, and memoirs in a variety of formats written by a variety of writers, some familiar to me, many new introductions, show “what it means to be Mexican American living in America today.”

The U.S. Hispanic population reached 62.5 million in 2021, up from 50.5 million in 2010. People of Mexican origin accounted for nearly 60% (or about 37.2 million people) of the nation's overall Hispanic population as of 2021. (Pew Research Center) Many teen readers will see themselves and their lives reflected in these stories, and many more will learn more about their Mexican American peers and their daily challenges in America.

“I lie down and my mind races.…which gets me thinking about all the things that get white washed in America, which leads me to the border wall and people saying we need to keep the Mexicans out, which gives me all kinds of bad feelings because even though I’m not Mexican-Mexican, I am Mexican-American. Someone in my past came over.” (from Lopex, Diana. “Morning People.” 91-2)

----------

Mario’s Notebook by Mary Atkinson

Traditionally, the United States has long been the global leader in resettling refugees, strictly defined as people forced to flee their home country to escape war, persecution or violence. (Smithsonian Magazine) The number of refugee children has increased over the past decade. With approximately 350 refugee resettlement agencies spread throughout nearly all 50 states, refugee children can be found in classrooms throughout the country. Together with immigrants, these newcomer children make up one in five children in the U.S. (https://brycs.org)

Many children look around their classrooms and wonder, Who are these kids and why are they here? Some parrot opinions heard from the adults in their lives—both positive and negative.

Mario, a survivor of the Salvadoran Civil War of the 1980s, was one of those newcomers. Mario witnessed his father, a journalist, being taken away from their home. “All I can do is watch. Watch as the soldiers blindfold Papa. Watch as they shove him out the door. Watch as Mama collapses to the floor.” (21) He later learns of the death of his father, killed by the soldiers.

Mario with his mother and younger brother are smuggled to the United States where they are given an apartment, food, clothes, and toys, and Mario wonders, “Will anything in my life ever feel right?” (44) Mario is enrolled in fifth grade where all the children accept him, especially twins William and LaShaunda, except for the class bully Randall. When discussing an article on deportation in social studies class, Randall has no trouble sharing his opinions. “My father says people like this should go back to their own countries. We didn’t ask them to come here.” (83)

And after a small incident in his father’s store, Randall threatens Mario and his family. “My father could get you kicked out of the country, you know.” (79)

Mario struggles with feelings of betrayal by his father’s political articles, actions which led to their current situation. When he finally has the courage to read the notebook his father left him—and the article his father signaled him to pull from the typewriter the night he was taken—he reaches understanding of his father’s heroism and the importance of letting the world know of the war, persecution, and violence occurring in his country.

Mary Atkinson’s short novel is not only a good story with engaging, well-developed characters, can serve as an effective tool for generating important conversations about refugee admissions and resettlement and the importance of opening our hearts (and our borders).

----------

Merci Suarez Series by Meg Medina

I knew when I first met Merci Suarez in the short story “Sol Painting” in the anthology Flying Lessons, that I would want to learn more about this young girl who was entering the confusing world of adolescence. I was thrilled when her story was expanded into a novel—and then a series.

Mercedes Suarez Changes Gears, the 2019 John Newbery Medal winner

Mercedes Suarez lives in Las Casitas, a community of three houses with her older brother Roli and parents, her aunt and two little nephews, and her beloved Lolo and Abuela. She began attending Seaward Pines Academy, where she is a scholarship student, last year. But now Merci is a sixth grader, and things are changing. It is not only that the students will be changing classes and teachers, it is not only that she has to deal with mean girls—or at least one mean girl and her sidekick, but her grandfather who has been her confidant and bike-riding partner is changing. It is not until a car accident that the family lets her in on the secret; Lolo has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

Her brother explains, “In the next few years, Lolo might not be able to remember us, Merci. He won’t even remember himself.”

Meg Medina’s newest novel for middle grade students features a Latina protagonist who is dealing with challenges that many middle-grade students face and a new challenge that many might face in the future. With the love of her family and the support of her new friends, Merci will decide if she can change gears.

This delightful read, full of engaging characters and sharing the day-to-day life of a busy family, reminded me of Medina’s novel YAQUI DELGADO WANTS TO KICK YOUR ASS but written at a level for 5th to 8th grade readers.

Merci Suarez Can’t Dance

When the science teacher asks Merci’s lab group, “What do you scientists predict would really happen in this catastrophic scenario (earthquake)?” Lena answers, “Everyone would be really upset. The ground under their feet would be moving in a way they hadn’t expected. Everything they thought was safe forever would be crumbling. They wouldn’t know how to make it better or what to do next. They’d want things like they were before.” (258) Lena is actually describing a real-life catastrophic scenario—the break in friendship between best friends Hannah and Merci, but she may as well be describing Mercedes Suarez’s entire year.

Now in seventh grade, Merci is still challenged by middle school drama, shifting friendships, and the unkind comments of other students, supported by her two best friends Lena and Hannah and her very close, extended family, but things have changed. “…really the world is just spinning. I’m sick with all the trouble I’m in and sick with all the things that are different this year, too.… Nobody is the way they’re supposed to be.” (188-9)

Merci’s brother has left for college, her aunt is dating, Hannah is hanging out with her enemy Edna, and Edna stands up for Merci against the school bully. No one is who Merci thinks they are. Preparing a science project, Merci reflects, “A geode sort of reminds me what Lolo used to say about people. That we all hold surprises.” (154) And later, she wonders, “Why are people so complicated? Bad guys should always be just bad guys, and good guys should always be good guys. That way you’d be able to like them or hate them all the way through.” (332)

On top of all this, her grandfather’s condition is worsening. “Lolo is barely moves. He’s fading like one of those colorful street paintings Mr. Cahill works on. ‘Everything vanishes,’ [Mr. Cahill] told us at the festival. ‘Live in the moment. That’s the whole point.’ I swallow hard just thinking about the fact that it’s true about people too. They vanish, sometimes a little at a time.” (314)

Merci also begins thinking about boys and kissing and new ethical issues; when an incident happens at the school dance, she can’t decide whether to own up or try to fix the problem. “Mami says feelings are tricky because sometimes they get disguised.” (92)

But through all of this, she does make a difference in her school. She explains the persistent microaggressions by Jason and the other kids at her private school to Miss McDaniels, “It’s like getting paper cuts all the time, miss. They don’t look like much, but they hurt, especially if you get a lot of them, day after day.” (337-8)

Maybe Merci Suarez can’t dance but maybe she can use dancing to make a difference.

Merci Suarez Plays It Cool

"True friends feed us in lots of ways.” (310)

Merci’s story continues in the summer before 8th grade. All her friends are away. Things at Las Casitas haven’t changed much although her aunt is still dating Simon, Roli can’t afford his next year of premed and is home working at Walgreen’s and planning to attend the local Junior College, and Marci’s grandfather Lolo’s Alzheimer’s is worsening. And Marco, the twins’ father shows up for the first time in years.

Before school begins, Tia pays for Merci to get a new haircut. “’Imagine walking into school looking like someone brand-new. Merci 2.0.’ I sit there blinking at the thought of being upgraded. Should I want to be someone new?’” (81) The new haircut is a success, but Merci questions, “But what about the old me? I wonder. Where will she go?” (82)

Merci has never been one of the popular crowd, but she has friends—Hannah, Lena, Edna (sort of a frenenemy), and Wilson who is a great friend but also possibly becoming a crush. The popular girls, Avery and Mercede,s are Merci’s soccer teammates, but she keeps hoping that they may become friends. “The whole time, though, I’m watching everyone at Avery’s table from the corner of my eye. Those kids are magnets, even though I don’t want them to be. What is it, I wonder, that makes them seem so cool? And more important, are they?” (107)

The year fluctuates between highs and lows.

----------

My Family Divided by Diane Guerrero (memoir)

"Suddenly we saw a white police van pull up. Seconds later, two guards herded some inmates out onto the curb. My mother was among them.." (124)

When Diane Guerrero was 14 years old, her undocumented immigrant parents were deported to Colombia. Her older step-brother having previously moved away, this left Diane, an American citizen, on her own in Boston, dependent on the charity of family friends. "Neither ICE nor the Massachusetts Department of Children and Families had contacted me. This meant that at fourteen, I'd been left on my own. Literally. The same authorities who deported my parents hadn't bothered to check whether I, a fourteen-year-old citizen of this country, would be left without family adult supervision, or even a home." (115)

An adaptation of her adult memoir, co-authored by Erica Moroz, describes the life of the television actress Before and After Deportation as she struggles with ambivalent feelings towards her parents, poverty, and depression. "[At my senior recital] I ended with a jazz standard called 'Poor Butterfly.' It's about this Japanese woman enchanted by an American man who never returns to be with her. I'd chosen it because it struck a powerful chord in me. The abandonment. The hoping and waiting and yearning for something that doesn't happen." (153)

But this is also the story of the 11.4 million unauthorized US immigrants (2018), 500,00 of whom were deported (2019), others who are living under the constant threat of deportation and a family divided.

----------

On the Hook by Francisco Stork

“Respect and disrespect. Killing and revenge and cowardice. Stupid, meaningless words, all of them. None of them worth dying for.” (270)

Hector and his family were still grieving the loss of his father to cancer, his brother dealing with it through drinking. But Hector was a good, smart kid on his way to a better life. Then things were finally looking up; Fili was drinking less, in love, and planning to buy a house to move the family out of the projects where Chavo, the drug dealer, and his brother Joey ran things. What would induce Hector, a chess team champion, writing contest winner with college aspirations, who worked a grocery job to help his mother pay the bills, to confess to a crime in order to end up in reform school.

At school and home in the projects, Joey threatens to kill Hector, carving a “C” in Hector’s chest, and Hector becomes consumed with the shame of his own cowardice. When Joey kills Fili, he and Hector are sent to the same reform school, where Hector has to decide how to make things “balance[d]” as decreed by the apparition of his father. Should he humiliate Joey in the boxing ring and then kill him? Will those acts make him less of a coward? Or does he listen to his many mentors?

“X-Man went suddenly quiet. He looked as if he was remembering something painful. ‘Dude, you gotta find a way to move on. When your flashlight’s stuck like that, you’re not seeing, like Mr. Diaz says. And seeing’s the only way to free yourself.’” (214)

Francisco Stork’s newest novel is filled with 3-dimensional characters who jump off the page into the reader’s heart. I felt protective of Hector, wanting to cheer him on and shake him and counsel him. I grieved for Fili and his lost future as if I had known him. Even Joey, the villain, came alive as his story validates the idea that everyone has a back story and their own demons.

Maybe the balance Hector needs to create is in himself.

----------

Silver Meadows Summer by Emma Otheguy

“Now Carolina saw [the road} like Papi saw it: white crest of salty water, foam and mist, a wave upon the sea, and one foot in front of the other. Cuba, Puerto Rico, New York, Carolina’s roots were not in the soil but in the rhythm of her family’s movement, step after step.” (193)

Carolina’s father lost his job in Puerto Rico, and the family—Papi, Mami, Daniel and 11-year old artist Carolina—move to upstate New York to live with her aunt, uncle, and popular 13-year-old cousin Gabriela. As Caro misses her homeland, she fights to retain her art, her culture, and her memories of Puerto Rico while living in the big house in a new development. When Tia Cuca tries to replace Ratoncita Perez, the mouse who leave money for children’s lost teeth, with her own version of the tooth fairy, Carolina realizes that she can accept, if not embrace, both cultures. Meanwhile Gabriela wants to learn more about her Cuban-Puerto Rican roots and to learn Spanish.

Carolina meets Jennifer, a fellow artist, who quickly become a best friend despite Mami finding her unsuitable and, as Carolina learns to stand up for herself, Gabriela learns to stand up to her friends and together Carolina, Gabriela, and Jennifer help to save the farmland that comprises Silver Meadows from becoming all development.

A story of culture, family, friendship, nature, accepting change, and making a difference.

----------

Singing with Elephants by Margarita Engle

Poetry is a dance of words on the page. (1)

Poetry is like a planet…

Each word spins

orbits

twirls

and radiates

reflected starlight. (10)

Poetry,

she said,

can be whatever you want it

to be. (25)

And poetry is what connects a lonely girl with a new neighbor who turns out to be Gabriela Mistral, the first Latin American (and only Latin American woman) winner of a Nobel Prize in Literature.

Poetry also helps this young girl to find her words and her courage to face a grave injustice.

Oriol is an 11-year-old Cuban-born child whose veterinarian parents moved to Santa Barbara where

the girls at school

make fun of me for being

small

brownish

chubby

with curly black hair barely tamed

by a long braid…

…call me

zoo beast

…the boys call me

ugly

stupid

tongue-tied

because my accent gets stronger

when I’m nervous, like when

the teacher forces me to read

out loud (7-8)

Oriol’s friends are her animals and the animals she helps with in their clinic and on the neighboring wildlife zoo ranch. She learns veterinary terminology from her parents and poetry terms from her new friend.

When the elephant on the zoo ranch owned by a famous actor gives birth to twins and one is taken from her family by the actor and held captive, Oriol, with the help of her mentor, her family, and her new friends, fight to reunite the baby with her mother and twin.

Readers learn Spanish phrases and quite a lot about poetry, animal rights, Gabriela Mistral, xenophobia, and courage.

courage

is a dance of words

on paper

as graceful as an elephant

the size of love (99)

I read this beautiful book, a must for grade 3-8+ classrooms and libraries, in an afternoon. I feel it is Cuban-American poet, the national 2017-19 Young People’s Poet Laureate, Margarita Engle’s, best writing although I have enjoyed, learned from, reviewed, and recommended a great many of her verse novels. As part of a poetry unit or a social justice unit, Oriol’s story will speak to readers and help move them to passion and action.

----------

The Long Ride by Marina Budhos

“You know, it’s a lot easier to be one side or the other. It’s harder to be in the middle. People don’t like the middle. That’s the bravest thing of all.” (178)

Jamila, Josie, and Francesca are best friends of mixed race in 1971 Queens, NY. Their plans for starting seventh grade with each other and their white schoolmates at the neighborhood junior high school change when they become part of social experiment—integration. Francesca’s parents send her to a private school where she doesn’t fit, while Josie and Jamila take a long bus ride to a predominately black school in a much rougher neighborhood. They hope they may fit in better there, but Jamila is too white for the girls and Josie is no longer in the advanced classes and worries about her future. The girls don’t fit into their new school neighborhood and their new friends don’t fit into their neighborhood.

As they try to navigate seventh grade, boyfriends, teachers, classes, narrator Jamila’s anger, and Josie’s shyness, Jamilla realizes, “if anyone had told me this was what being in junior high would be like: Your best friend is silent beside you. You’re skinny and knock-kneed and you get lost easily. You aren’t at the top of the Ferris Wheel. I’d have said: You can have it. (60)

The world seemed to have changed. “…I’m starting to notice that something bigger s going on in the city. Everyone is edgier, angry. You can feel it in the way people squint through the bus windows.

----------

The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo

The power of words – to celebrate, to heal, to communicate, to feel.

Fifteen-year-old Xiomara grabbed me immediately with her words. She sets the scene in “Stoop-Sitting”: one block in Harlem, home, church ladies, Spanish, drug dealers, and freedom that ends each day with the entrance of her Mami.

Xiomara feels “unhide-able,” insulted and harassed because of her body. We meet her family—the twin brother whom she loves but can’t stand up for her and a secret that he is hiding; her father who was a victim of temptation, and now stays silent; her mother, taken away from the Dominican Republic and her calling to become a nun and forced into a marriage that was a ticket to America; and Caridad, her best friend—only friend—and conscience,

Bur Xio fills her journal with poetry and when she discovers love, or is it lust, she finds the one person with whom she can share her poetry.

“He is not elegant enough for a sonnet,

too well thought-out for a free write,

Taking too much space in my thoughts

To ever be a haiku.” (107)

Aman gives Xio the confidence to see what she can become, not what she is told she can be, and to appreciate, rather than hide, her body. “And I think of all the things we could be oif we were never told out bodies were not built for them.” (188)

She also begins to doubt religion and defy the endless rules her mother has made about boys, dating, and confession. With the urging of her English teacher, Xio joins the Poetry Club and makes a new friend, Isabelle “”That girl’s a storyteller writing a world you’re invited to walk into.” (257) and with the support of Isabelle, Stephan, and Chris “My little words feel important, for just a moment.” (259)

When her mother discovers that Xio has not been attending her confirmation class, things come to a climax; however, even though her obsession with poetry has destroyed relationships in her family, it also, with some “divine intervention,” becomes the vehicle to heal them.

As I read I wanted to hear Xio’s poems, but when I finished the book, I realized that I had. A novel for mature readers, The Poet X features diverse characters and shares six months’ of interweaving relationships built on words.

----------

Warrior Girl by Carmen Tafolla

“Freedom isn’t a ‘thing’ you can stick in a box

and say, ‘there it is.’

It’s a living struggle we keep protecting every day,

Each one of us a warrior, defending Freedom’s way.” (ARC 194)

Through her story and her poetry, readers learn about Celina Teresa (Tere), last name (misspelled on the birth certificate by the nurse) Guerrera which means “a Woman Warrior,” and we watch her grow into her name as she learns about the power her words and actions can have.

Tere has a wonderful family—her mother who is training to be a nursing assistant and has the dream of becoming a nurse; her grandmother, a rebel in her own teenage years; and her father, already deported once, who moves the family from place to place, trying to find work so he can afford ”the right papers.”

And excited about starting school, readers will cringe as teachers change young Mexican-American Tere’s name to Terry, stop her from speaking Spanish and coloring Cinderella’s hair black, and teach a racist view of the Alamo.

“Felt like Life had slapped her hard hand

over my mouth

and tried to shut me up,

tried to keep me

from being me,…” (ARC 1)

But finally she has a teacher who tells his students that their voices matters.

And when, in a final move in middle school, the family moves in with Gramma near her tia and cousin, she decides

“No matter what, they will not silence me.

They will not take my story or my joy

away from me.” (ARC 18)

And in this school with three new best friends—Liz, Cata, and Chato, Celina Teresa, now called Celi, begins to write poetry—thanks to her English teacher, Ms. Yanez, and learns real history from Mr. Mason who learns some history from Celi herself.

“…so history gets retold in different ways by different people,

and sometimes legends and heroes turn out t to be no-so-heroic.” (ARC 58)

Celi learns to deal with people, like classmate Heather, who make uninformed comments by explaining Mexican customs to them and obtaining another friend who shares her culture.

And she learns the power her words can have. “Wow! It’s amazing how many people you can reach with a poem!” (ARC 114)

When Ms. Yanez talks about social justice, Celi thinks,

“I was named Guerra, warrior, for a reason.

Because I was meant to be a warrior too.

Meant to be. And AM!

Fighting with my weapons—paper and pen.

Using my courage to speak up.

Using celebration spirit to keep me strong,

so I never give up.

Because guerreras never stop

fighting for what they believe in.” (ARC 125)

Through the sadness of her father’s second deportation and then COVID, Celi and her friends never stop making “this place better.”

What an important novel for our readers to show them that everyone matters, every has a voice, and everyone can be a warrior to make this place we live in better. Carmen Tafolla’s verse novel should be in every upper elementary and middle grade classroom and school library—and would make an effective mentor text for writing lessons.

----------

Wings in the Wild by Margarita Engle

2018: Teen refugees from two different worlds. Soleida, the bird-girl (La Nina Ave), is fleeing an oppressive Cuban government who has arrested her parents, protesters of artistic liberty, their hidden chained-bird sculptures exposed during a hurricane; she is stranded in a refugee camp in Costa Rica after walking thousands of miles toward freedom. Dariel is fleeing from a life in California where he plays music that communicates with wild animals but also where he and his famous parents are followed by paparazzi and his life is planned out, complete with Ivy League university. When a wildfire burns his fingertips, he decides to go with his Cuban Abuelo to interview los Cubanos de Costa Rica for his book. And then he decides to stay to study, hopefully to save, the environment.

When Soleida and Dariel meet, he helps her feel joy—and the right to feel joy—again, and they fall in love, combining their shared passions for art and music, artistic freedom, and eco-activism into a human rights and freedom-of-expression campaign to save Soleida’s parents and other Cuban artists and to save the endangered wildlife and the forests through a reforestation project. This soulful story, beautifully and lyrically written by the 2017-19 Poetry Foundation's Young People's Poet Laureate Margarita Engle is not as much a story of romance but of a combined calling to save the planet and the soul of the people—art. Soleida and Dariel join my Justice & Change Seekers.

Wings In the Wild also reintroduces two of my favorite characters, Liana and Amado from Your Heart-My Sky who “became local heroes by teaching everyone how to farm during the island’s most tragic time of hunger.” (5)

----------

For lessons and strategies to group and read these novels in Book Clubs where readers can work together, see Talking Texts: A Teacher’s Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum.

See other reviews of recently published, read, and recommended novels by topics for Grades 4-12 in the drop-down menu under BOOK REVIEWS.

Here I review 23 of my more-recently read.

----------

Big Apple Diaries by Alyssa Bermudez (memoir)

Big Apple Diaries is based on the author’s actual journals which she has illustrated as a graphic diary memoir encompassing the time from September 2000 to June 2002.

Alyssa Bermudez was the child of divorced parents, dividing her time between her Puerto Rican father who lived in Manhattan and her Italian-British mother who lived in Queens. This diary begins in 7th grade where “It seems that suddenly every grade you get and everything you do matters…. Now our friends are obsessed with who has a crush on who. And who is the coolest. There is all of this pressure to be popular and smart or face a dim future being a weirdo with no job.” (10)

Alyssa is not particularly popular, but not particularly unpopular either, has a much older half-brother and two best friends, Lucy and Carmen, and is an artist who wants to become a shoe designer. In this 7th grade year, she experiences her first crush—Alejandro from Columbia. Her diary takes us through the typical middle school year familiar to most of our adolescent readers. “Yesterday I did something very stupid. I knew it was stupid at the time and I still did it anyway. It’s like the drive to be popular makes me see things through stupid lenses.” (83) Typical preteen, she does many “stupid things”: shave her eyebrows, accidently dye her hair orange, cut school.

Two months before her thirteenth birthday, the attacks of September 11th occur. Alyssa’s mother worked in a building that faced the Twin Towers. She escaped and caught the last train to Queens. Her father did work in the World Trade Center but was meeting a client in Jersey City that morning (and bought skates to skate the 19.5 miles back to his Manhattan home). Overcome with emotion, Alyssa writes no entries for that day and the following few.

After that time Alyssa recognizes, “I sort of feel like I have no control over anything. I want to come back to the normal life I knew and the Twin Towers that I visited with Dad all the time.”(195) She finds herself changing, maturing: “When things can change in an instant, it’s hard to accept it. I want to make the right decisions and prove my worth. I want to be brave.” (211)

On her thirteenth birthday she begins to wonder “Who am I?” and begins thinking about her character and how she may want to change. Her diary takes the reader through graduation to a future where “Some things I’ll take with me and other things I will leave behind.” (274)

Big Apple Diaries, a graphic memoir of an NYC adolescent who experienced 9/11 as part of her middle grade years adds yet another perspective or dimension to other novels written about 9/11.

----------

Clap When You Land by Elizabeth Acevedo

One plane crash. One father’s death. Two families’ loss.

“Papi boards the same flight every year.” (18) This year when her father leaves for his annual 3 months in his homeland, his daughter Yahaira knows the secret he has kept for 17 years. But she is unaware of who else knows. Not Camino, the other daughter who is practically Yahaira’s twin. Camino only knows she has a Papi who lives and works in New York City nine months a year to support her and the aunt who has raised her since her mother died.

When Papi’s plane crashes on its way from New York to the Dominican Republic, all passengers lose their lives and many families are left grieving. But none are more affected than the two daughters who loved their Papi, the two daughters whose mothers he had married.

“It was like he was two

Completely different men.

It’s like he split himself in half.

It’s like he bridged himself across the Atlantic.

Never fully here or there.

One toe in each country.” (360)

Sixteen year old Yahaira lives in NYC, a high school chess champion until she discovered her father’s secret second marriage certificate and stopped speaking to him and stopped competing, and has a girlfriend who is an environmentalist and a deep sense of what’s right. “This girl felt about me/how I felt about her.” (77)

Growing up in NYC, Yahaira was raised Dominican.

“If you asked me what I was,

& you meant in terms of culture,

I’d say Dominican.

No hesitation,

no question about it.

Can you be from a place

you have never been? “ (97)

Sixteen year old Camino’s mother died quite suddenly when she was young, and she and her aunt, the community spiritual healer, are dependent on the money her father sends. Not wealthy by any means, they are the considered well-off in the barrio where Papi was raised; Camino goes to a private school and her father pays the local sex trafficker to leave her alone.

And then the plane crash occurs.

“Two months to seventeen, two dead parents,

& an aunt who looks worried

Because we both know, without my father,

Without his help, life as we’ve known it has ended.” (105)

Camino’s goal has always been to move to New York, live with her father, and study to become a doctor at Columbia University. Finding out about her father’s family in New York, she makes a plan with her share of the insurance money from the airlines. But Yahaira has her own plan—to go to her father’s Dominican burial despite the wishes of her mother, meet this sister, and explore her culture.

When they all show up, readers see just how powerfully a family can form.

“my sister

grasps my hand

I feel her squeeze

& do not let go

hold tight.” (353)

“It is awkward, these familial ties

& breaks we share.” (405)

After the crash of American Airlines Flight 587 just two months after 9/11/2001, it was sometimes a spontaneous reaction for passengers to clap when the plane landed, one of “the many ways Dominicans celebrate touching down onto our island.” (Author’s Note).

----------

Disappeared and Illegal by Francisco Stork

Francisco’s Stork’s novel Disappeared takes place in Juarez, Mexico, and depicts sex trafficking, the cartel, murder, poverty, betrayal, abandonment.

Sara Zapata, a young reporter for a local paper, is committed to finding and saving the young women she learns are being kidnapped, including her best friend Linda, despite the warnings of her boss and the threats to herself and her family.

Sara’s younger brother Emiliano, whose life has been affected by his father’s abandonment—of the family and his native Mexico—is looking for a better life, for ways to make money to pay the family bills and win the love of his wealthy girlfriend.

The siblings find in following their consciences, helping others, and making moral choices, they need to do what is right—not what is easy or even safe, and must sacrifice, or revise, their personal goals. To save their lives, Sara and Emiliano escape to the United States to find a better life and to bring the cartel who is trafficking the women to justice. They cross the border and are attacked in the dessert.

Sara turns herself over to the authorities, certain that she meets the requirements for asylum but, as her time in the detention facility grows longer and she observes women being mistreated and deported for no reason, she questions her assumptions. “I imagined that all I had to do was show the authorities the evidence of actual persecution, of actual threats, such as people machine-gunning our house in Juarez.… I saw my case as fitting within the legal reasons for asylum under the law of the United States. Was I wrong about the United States?” (31) She finds, “The whole process of who gets asylum and who gets detained, who gets a bond and who gets released, who gets a visa and who gets deported. I mean, it’s not as rational as I imagined it would be.” (34)

Meanwhile Emiliano enters the country illegally and goes to Chicago with his father, planning to turn Linda’s evidence against the cartel over to the proper authorities. He also finds America to be less than welcoming. As he tells his new friend Aniela, “I think that in Mexico I feel like I belong all the time. I never feel not wanted like I do here sometimes. Here I’m always looking over my shoulder even when no one is there.…knowing that you belong and are wanted is major.” (251)

When Sara’s attorney is killed and she is placed in solitary confinement and Emiliano finds he can no longer trust his father, tensions escalate. A study of government corruption and the asylum process, this sequel to Disappeared is a thriller that will hook the most reluctant adolescent reader. Enough background is given in Illegal that it may not be completely necessary to read Disappeared first but it would surely enhance the reading.

----------

Falling Short by Ernesto Cisneros

“I’m not sure everyone has a best friend like I do. No, not the average “bestie” you pretty much only see and talk to at school. I’m talking best friends who know you inside and out. Friends you feel comfortable enough to cry or change in front of, friends so close that they feel more like a brother or sister.

That’s what I’ve got in Isaac.

And I would do anything for him. Just like he’d do for me.” (180)

Sixth graders Isaac and Marco are best friends not only because they are very, very good friends but because they each want the best for the other. Isaac is athletically gifted and a star of the basketball team but has problems with school work; Marco is academically gifted but wants to become an athlete to win the approval of his father who left home for a new girlfriend and her son. Isaac’s father also left home but because his drinking problem has gotten the best of him. “Drinking had pretty much become more important than either Ama or me.” (92)

When the very short Marco learns of 5’3” NBA player Muggsy Bogues, he decides to try out for the school basketball team and, with the determination he applies to everything, studies YouTube videos and practices nonstop. Isaac becomes his coach and even figures out how he can change his plays to help Marco be successful. “That’s probably the one thing that separates [Isaac] from every other kid I’ve ever met. He never judges me. Never makes me feel stupid.” (154) And when Isaac helps Marco with his schoolwork (in a strange turn of events), he learns that he is smarter than he thought.

Told in alternating narratives by Isaac and Marco, this is a story of true friendship, broken families, bullying, sports (I learned a lot of basketball terms!), teamwork and collaboration, featuring Latinx and Jewish characters. It is story of what is takes to not fall short.

----------

Far from the Tree by Robin Benway

Melissa Taylor was their mother. That is what Grace. Maya, and Joaquin have in common. But it is enough to make them "family" when they meet as teenagers. All three were given up at birth or shortly thereafter: Grace to a loving middle-class family; Maya to a wealthy family who then had their own biological child—and their own problems; and Joaquin to a lifetime of foster homes.

Then 16-year-old Grace has her own baby, and, after her child Milly is adopted, Grace yearns to finds her biological mother.

When the three siblings meet, they immediately bond and help each other, not only find the part of their identity they thought missing, but they help each other fit into their present families and lives and discover that it is possible to have two families and feel complete. Maya is able to accept her place as the only brunette in a family of tall redheads and forgive a mother who is an alcoholic; Joaquin is ready to value himself and trust enough to let himself be adopted; and Grace can forgive herself for giving her baby a life apart from her.

These are characters who get under your skin as soon as you meet them.

Far from the Tree won the 2017 National Book Award for Young People's Literature.

----------

Farewell Cuba, Mi Isla by Alexandra Diaz

“Look outside your window, children,” Mami said as they took their seats. “You may never see your country again.” (ARC, 36)

Victoria had a wonderful life in Cuba where she lived with her mother, father, and younger sister and brother. Also in the same duplex lived her cousin Jackie, her aunt, her uncle, and her baby cousin/godson. Even though they were very different and attended different schools in Havana, 12-year-old Victoria and Jackie were best friends, and they both spent time at their Papalfonso and Mamlara’s finca where Victoria rode her horse and swam with her cousin, a ranch that Victoria would inherit.

October 1960: With Fidel Castro in power and protestors arrested, news restricted, and professionals prohibited from leaving the country, Victoria’s family makes the decision to go to Miami, expecting their exile to “only last a few weeks, until the U.S. presidential election.” (14)

Alternating chapters focus on Victoria and Jackie and permit readers to learn what is happening in Cuba and about the Cuban community in Miami. Here Victoria lives in poverty (her father’s engineering degree of no use as he labors for minimum wage), and she tries to take charge of feeding her family. When Jackie arrives in Miami through the Peter Pan Project (reminiscent of the Holocaust Kindertransport), readers see how being apart from her immediate family affects her and her relationship with Victoria.

I often have read and reviewed novels (and memoirs) by Margarita Engle and noted that I learned quite a lot of Cuban history, a history missing from my education. Diaz’s novel, inspired by the experiences of her mother and family who came to the

United States from Cuba in 1960, spans October 1960 to June 1961 and teaches readers even more about Castro and his effect on Cuba and the Cuban citizens and the role the U.S. government played. This novel should be included in every American history course. This is also a story of prejudice, as experienced by Katya, Victoria’s Russian school friend, and of resilience and family. The Author’s Note further expands on the historical facts and includes a glossary of Cuban terms.

----------

First Rule of Punk by Celia Perez

The first rule of punk is to “be yourself,” but that’s hard when your mom moves you a thousand miles from your home, friends, and father in Florida for two years in Chicago; when your SuperMexican Mom is always criticizing your Spanish, your clothes, and your vegetarianism; when the Mexican students in your new school call you a coconut—brown on the outside and white on the inside, and your new principal finds your talent not traditional enough to honor the man the school is named after.

Maria Luisa, or Malu, is the child of a divorced English professor mother and a record-store owner father. She makes zines, hates cilantro and spicy food, speaks mostly English, and loves punk. She feels “like Mom’s Maria Luisa and my Malu are two different people. The only thing we have in common is an accent over a vowel.”

She and her mother move to a Mexican neighborhood and middle school in Chicago, and Malu is not sure she will make friends (especially after meeting Mean Girl Selena), but she meets a group of outsiders and talks them into forming a punk rock band, the Co-Co’s. When their act is cut from performing at the school’s Fall Fiesta for not “fitting in,” Malu plans an Alterna-Fiesta talent show where they will perform and she will sing in Spanish a song that is “not your abuela’s music. “I looked over at Joe, Benny, and Ellie, who were blowing straw wrappers at each other. ‘My friends.’ I might have actually found my Yellow-Brick-Road posse.” (318)

Told through a mixture of prose and vines.

----------

How to Build a Heart by Maria Padian

According to the DODEA, “Children who experience the loss of a parent or other family member through a military line-of-duty death are likely to face a number of unique issues.” Izzy’s father died when she was ten, before her younger brother Jack was born. Her small family, estranged from her father’s relatives, has moved from place to place as her mother, a nurse’s aide, tries to support them.

When she moves to a a trailer park in Virginia, Isabella Crawford becomes embroiled in the family drama of her best friend, and, as a member of the acapella group at the private school where she is a scholarship student, she befriends a freshman who is battling her own demons. To make her life even more complicated, her family becomes the recipient of a Habit for Humanity house, and Izzy has to volunteer hours towards its construction.

In the midst of all this drama, Izzy, who is determined to keep her family’s circumstances a secret from her classmates, discovers what friendship and trusting friends—and family—really means as she reconnects with her father’s pig-farming family and finds that her wealthy friends and her new boyfriend care about her, not her economic status.

Izzy, an adolescent straddled between two cultures—that of her Puerto Rican mother and her North Carolina father—is not quite sure where she belongs but learns to share her world with others.

----------

I Am Not Alone by Francisco Stork

Usually when I finish a novel, my book is full of stickies marking quotes I want to use in my review. However, halfway through I Am Not Alone, I realized that I hadn’t marked any passages, too intent in following Alberto and Grace’s journeys to justice, maybe even salvation, and possibly each other—and solving a mystery.

Alberto is an undocumented teen immigrant from Mexico who lives with his sister and her baby. He works very hard to keep Lupe recovered from her drug addiction and tries to convince her to leave Wayne, her abusive boyfriend who is the married father of her baby, the owner of their apartment, and Alberto’s boss. He also has quit high school to work many hours to send most of his $7/hour paycheck to his mother and sisters in Mexico. Adding to his challenges, Alberto is struggling with the onset of schizophrenia and hears a voice in his head, which he refers to as “Captain America,” that prescribes his actions and constantly gives him critical thoughts about himself.

I first met Alberto and Captain America in Stork’s 2018 short story “Captain, My Captain” in Unbroken: Stories Starring Disabled Teens, a story limited to Alberto’s perspective.

In this novel, readers are also introduced to Grace, a high school senior. Grace is a high achiever and thinks she has her life plan figured out: boyfriend Michael, high school valedictorian, Princeton college, and then medical school to become a pyschiatrist like her father. Still reeling from her father leaving and her parents’ divorce, Alberto comes to clean her windows after a paint job, and Grace’s world falls apart as she begins to question her goals and even the meaning of love.

Readers also meet Grace’s supportive mother, her paternal grandfather and young cousin Benny, and Alberto’s house painting co-workers Jimbo and the drug-dealing Lucas.

Then the elderly resident of the apartment that Alberto, Jimbo, and Lucas were painting is murdered, and the evidence points to Alberto who is afraid that Captain America made him kill the woman. As Alberto looks for clues and Grace separately tries to prove his innocence, involving her grandfather, Benny, and their rabbi, and even the police detective, Alberto—and Grace—learn the meaning of friendship and community and believing in oneself and others.

This is an important novel about mental illness, the role religion can play, and unrestricted friendship for those teens who may just need this story to accept themselves or their peers. It also highlights the challenges faced by undocumented youth. Approximately 620,000 K-12 students in the United States are undocumented; more than half of K-12 undocumented students (54%) are from Central and South American countries, including Mexico (130,000), Honduras (50,000), Guatemala (40,000), and El Salvador (30,000).

For ideas to use “Captain, My Captain” in lessons to foster mental health literacy in the classroom, see Roessing, Lesley and Jessica Traylor. “Exploring Mental Health Literacy through Book Clubs.” Fostering Mental Health Literacy through Adolescent Literature, edited by Eisenbach, Brooke and Jason Scott Frydman, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2021.

----------

Living Beyond Borders: Stories about Growing Up Mexican in America by Margarita Longoria, ed.

As Mexican-Americans, we have always needed to defend who we are, where we were born, and prove to others that we are in fact Americans. (Editor’s Intro)

Twenty YA stories, essays, and memoirs in a variety of formats written by a variety of writers, some familiar to me, many new introductions, show “what it means to be Mexican American living in America today.”

The U.S. Hispanic population reached 62.5 million in 2021, up from 50.5 million in 2010. People of Mexican origin accounted for nearly 60% (or about 37.2 million people) of the nation's overall Hispanic population as of 2021. (Pew Research Center) Many teen readers will see themselves and their lives reflected in these stories, and many more will learn more about their Mexican American peers and their daily challenges in America.

“I lie down and my mind races.…which gets me thinking about all the things that get white washed in America, which leads me to the border wall and people saying we need to keep the Mexicans out, which gives me all kinds of bad feelings because even though I’m not Mexican-Mexican, I am Mexican-American. Someone in my past came over.” (from Lopex, Diana. “Morning People.” 91-2)

----------

Mario’s Notebook by Mary Atkinson

Traditionally, the United States has long been the global leader in resettling refugees, strictly defined as people forced to flee their home country to escape war, persecution or violence. (Smithsonian Magazine) The number of refugee children has increased over the past decade. With approximately 350 refugee resettlement agencies spread throughout nearly all 50 states, refugee children can be found in classrooms throughout the country. Together with immigrants, these newcomer children make up one in five children in the U.S. (https://brycs.org)

Many children look around their classrooms and wonder, Who are these kids and why are they here? Some parrot opinions heard from the adults in their lives—both positive and negative.

Mario, a survivor of the Salvadoran Civil War of the 1980s, was one of those newcomers. Mario witnessed his father, a journalist, being taken away from their home. “All I can do is watch. Watch as the soldiers blindfold Papa. Watch as they shove him out the door. Watch as Mama collapses to the floor.” (21) He later learns of the death of his father, killed by the soldiers.

Mario with his mother and younger brother are smuggled to the United States where they are given an apartment, food, clothes, and toys, and Mario wonders, “Will anything in my life ever feel right?” (44) Mario is enrolled in fifth grade where all the children accept him, especially twins William and LaShaunda, except for the class bully Randall. When discussing an article on deportation in social studies class, Randall has no trouble sharing his opinions. “My father says people like this should go back to their own countries. We didn’t ask them to come here.” (83)

And after a small incident in his father’s store, Randall threatens Mario and his family. “My father could get you kicked out of the country, you know.” (79)

Mario struggles with feelings of betrayal by his father’s political articles, actions which led to their current situation. When he finally has the courage to read the notebook his father left him—and the article his father signaled him to pull from the typewriter the night he was taken—he reaches understanding of his father’s heroism and the importance of letting the world know of the war, persecution, and violence occurring in his country.

Mary Atkinson’s short novel is not only a good story with engaging, well-developed characters, can serve as an effective tool for generating important conversations about refugee admissions and resettlement and the importance of opening our hearts (and our borders).

----------

Merci Suarez Series by Meg Medina

I knew when I first met Merci Suarez in the short story “Sol Painting” in the anthology Flying Lessons, that I would want to learn more about this young girl who was entering the confusing world of adolescence. I was thrilled when her story was expanded into a novel—and then a series.

Mercedes Suarez Changes Gears, the 2019 John Newbery Medal winner

Mercedes Suarez lives in Las Casitas, a community of three houses with her older brother Roli and parents, her aunt and two little nephews, and her beloved Lolo and Abuela. She began attending Seaward Pines Academy, where she is a scholarship student, last year. But now Merci is a sixth grader, and things are changing. It is not only that the students will be changing classes and teachers, it is not only that she has to deal with mean girls—or at least one mean girl and her sidekick, but her grandfather who has been her confidant and bike-riding partner is changing. It is not until a car accident that the family lets her in on the secret; Lolo has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

Her brother explains, “In the next few years, Lolo might not be able to remember us, Merci. He won’t even remember himself.”

Meg Medina’s newest novel for middle grade students features a Latina protagonist who is dealing with challenges that many middle-grade students face and a new challenge that many might face in the future. With the love of her family and the support of her new friends, Merci will decide if she can change gears.

This delightful read, full of engaging characters and sharing the day-to-day life of a busy family, reminded me of Medina’s novel YAQUI DELGADO WANTS TO KICK YOUR ASS but written at a level for 5th to 8th grade readers.

Merci Suarez Can’t Dance

When the science teacher asks Merci’s lab group, “What do you scientists predict would really happen in this catastrophic scenario (earthquake)?” Lena answers, “Everyone would be really upset. The ground under their feet would be moving in a way they hadn’t expected. Everything they thought was safe forever would be crumbling. They wouldn’t know how to make it better or what to do next. They’d want things like they were before.” (258) Lena is actually describing a real-life catastrophic scenario—the break in friendship between best friends Hannah and Merci, but she may as well be describing Mercedes Suarez’s entire year.

Now in seventh grade, Merci is still challenged by middle school drama, shifting friendships, and the unkind comments of other students, supported by her two best friends Lena and Hannah and her very close, extended family, but things have changed. “…really the world is just spinning. I’m sick with all the trouble I’m in and sick with all the things that are different this year, too.… Nobody is the way they’re supposed to be.” (188-9)

Merci’s brother has left for college, her aunt is dating, Hannah is hanging out with her enemy Edna, and Edna stands up for Merci against the school bully. No one is who Merci thinks they are. Preparing a science project, Merci reflects, “A geode sort of reminds me what Lolo used to say about people. That we all hold surprises.” (154) And later, she wonders, “Why are people so complicated? Bad guys should always be just bad guys, and good guys should always be good guys. That way you’d be able to like them or hate them all the way through.” (332)

On top of all this, her grandfather’s condition is worsening. “Lolo is barely moves. He’s fading like one of those colorful street paintings Mr. Cahill works on. ‘Everything vanishes,’ [Mr. Cahill] told us at the festival. ‘Live in the moment. That’s the whole point.’ I swallow hard just thinking about the fact that it’s true about people too. They vanish, sometimes a little at a time.” (314)

Merci also begins thinking about boys and kissing and new ethical issues; when an incident happens at the school dance, she can’t decide whether to own up or try to fix the problem. “Mami says feelings are tricky because sometimes they get disguised.” (92)

But through all of this, she does make a difference in her school. She explains the persistent microaggressions by Jason and the other kids at her private school to Miss McDaniels, “It’s like getting paper cuts all the time, miss. They don’t look like much, but they hurt, especially if you get a lot of them, day after day.” (337-8)

Maybe Merci Suarez can’t dance but maybe she can use dancing to make a difference.

Merci Suarez Plays It Cool

"True friends feed us in lots of ways.” (310)

Merci’s story continues in the summer before 8th grade. All her friends are away. Things at Las Casitas haven’t changed much although her aunt is still dating Simon, Roli can’t afford his next year of premed and is home working at Walgreen’s and planning to attend the local Junior College, and Marci’s grandfather Lolo’s Alzheimer’s is worsening. And Marco, the twins’ father shows up for the first time in years.

Before school begins, Tia pays for Merci to get a new haircut. “’Imagine walking into school looking like someone brand-new. Merci 2.0.’ I sit there blinking at the thought of being upgraded. Should I want to be someone new?’” (81) The new haircut is a success, but Merci questions, “But what about the old me? I wonder. Where will she go?” (82)

Merci has never been one of the popular crowd, but she has friends—Hannah, Lena, Edna (sort of a frenenemy), and Wilson who is a great friend but also possibly becoming a crush. The popular girls, Avery and Mercede,s are Merci’s soccer teammates, but she keeps hoping that they may become friends. “The whole time, though, I’m watching everyone at Avery’s table from the corner of my eye. Those kids are magnets, even though I don’t want them to be. What is it, I wonder, that makes them seem so cool? And more important, are they?” (107)