- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

- Asian, Asian-American

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

15. Rhyming AD JINGLES as Persuasive Writing

"Hold the pickles; hold the lettuce.

Special orders don't upset us.

All we ask is that you let us

Serve it your way…" (Burger King jingle)

Formerly, rhyming ads and jingles were popular in advertising. Rhyme (and rhythm) is an effective mnemonic device. As National Poetry Month winds down, have students write persuasive ads to sell a product—actual or invented—as a rhyming jingle. As “arguments,” ads should include reason(s) to buy and attributes of the product (as evidence to support the reasons).

"Hold the pickles; hold the lettuce.

Special orders don't upset us.

All we ask is that you let us

Serve it your way…" (Burger King jingle)

Formerly, rhyming ads and jingles were popular in advertising. Rhyme (and rhythm) is an effective mnemonic device. As National Poetry Month winds down, have students write persuasive ads to sell a product—actual or invented—as a rhyming jingle. As “arguments,” ads should include reason(s) to buy and attributes of the product (as evidence to support the reasons).

14. Using FOUND POETRY to determine important details and synthesize reading.

FOUND POETRY is a type of poetry created by taking words, phrases, and sometimes whole passages from a text and reframing or reformulating them as poetry by making changes in spacing and lines, or by adding or deleting text, thus imparting new meaning. I always tell students that they can add some words of their own, thereby further synthesizing their reading.

Instructions to Readers/Writers:

In my Teacher Example from Roessing, L. THE WRITE TO READ: Response Journals That Increase Comprehension, based on the text “The Kind of Face Only a Wasp Could Trust,” in Discovery Magazine (Netting, 2005), I wrote a Found Poem, using phrases from the article, to which I added a conclusion, thereby synthesizing my reading.

Black Splotches

Denoting social status

Bringing less work,

Showing body strength

Revered - always.

Cheaters

Sign of weakness,

Bringing humiliation,

Causing harassment.

Caught - always.

Wasp or Human--

It doesn’t pay

to lie.

The more important point to this strategy, rather than creating good poetry, is that readers go back to the text multiple times for deeper reading and learning and their poetry shows what they thought was important in the text.

FOUND POETRY is a type of poetry created by taking words, phrases, and sometimes whole passages from a text and reframing or reformulating them as poetry by making changes in spacing and lines, or by adding or deleting text, thus imparting new meaning. I always tell students that they can add some words of their own, thereby further synthesizing their reading.

Instructions to Readers/Writers:

- Read the article or novel or textbook section

- Highlight (or jot) the important words, phrases, or details from the text.

- When you finish reading, go back and cross out anything that turned out not to be important. (It would be advantageous for students to read the text through once and then go back and highlight the important details, but, realistically, many readers will resist reading a text twice—unless we "trick" them into it).

- Use the highlighted words/phrases in any order to build your poem.

- You may add any words they find appropriate/necessary.

In my Teacher Example from Roessing, L. THE WRITE TO READ: Response Journals That Increase Comprehension, based on the text “The Kind of Face Only a Wasp Could Trust,” in Discovery Magazine (Netting, 2005), I wrote a Found Poem, using phrases from the article, to which I added a conclusion, thereby synthesizing my reading.

Black Splotches

Denoting social status

Bringing less work,

Showing body strength

Revered - always.

Cheaters

Sign of weakness,

Bringing humiliation,

Causing harassment.

Caught - always.

Wasp or Human--

It doesn’t pay

to lie.

The more important point to this strategy, rather than creating good poetry, is that readers go back to the text multiple times for deeper reading and learning and their poetry shows what they thought was important in the text.

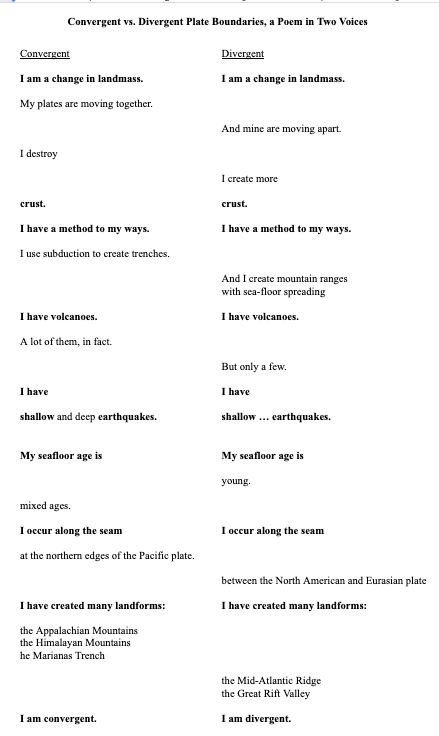

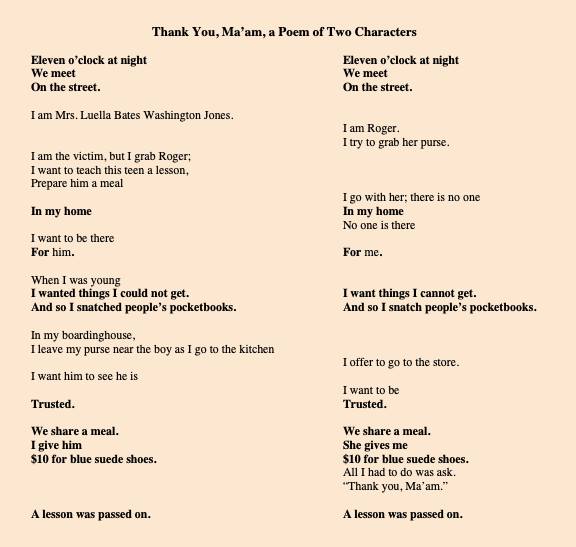

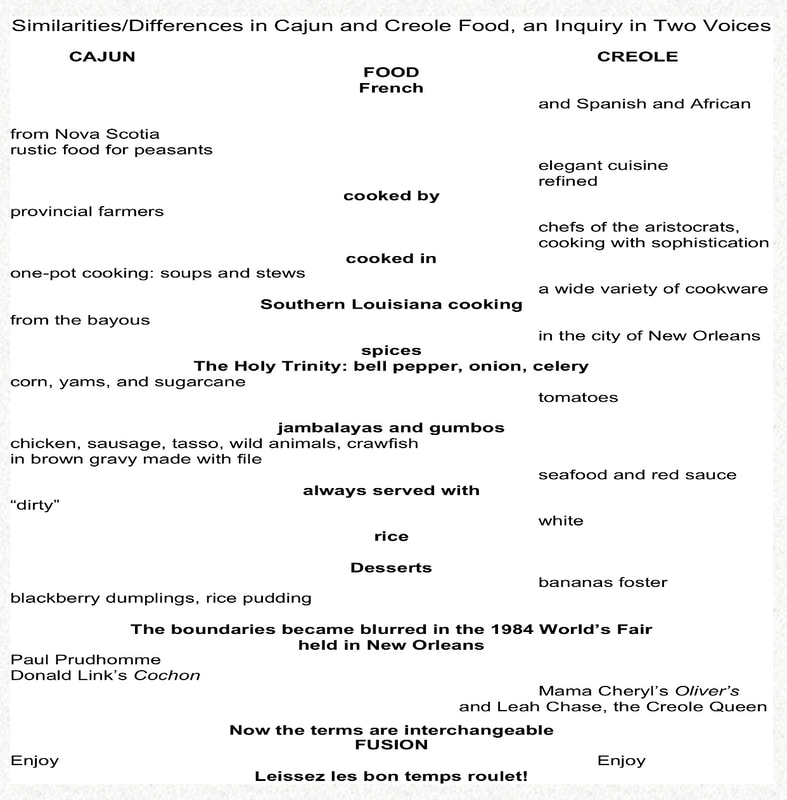

13. POETRY IN TWO VOICES TO COMPARE & CONTRAST (and present multiple viewpoints)

As informed citizens, we compare and contrast constantly. We decide which politician will garner our vote, which route to take to work, which outfit is most appropriate for a particular activity. Comparing-contrasting is a decision strategy, one that is crucial to teach our students. It requires the engagement of critical thinking, such as analysis, to discover subtle, but important, differences and unexpected similarities between two subjects as adolescents learn to compare and contrast in meaningful ways to make informed decisions. Comparing and contrasting based on text read is crucial for deeper understanding, and readers need scaffolding to determine important information and organize it. One way of doing so is by writing poetry in two voices. (from Roessing, L. After-Reading Response: Poetry in Two Voices to Compare and Contrast. AMLE Magazine)

What is Poetry in Two Voices?

In English-Language Arts classes, readers-writers can compare and contrast two characters from the same text or from difference texts or themselves and a character from a text. In the content areas students can compare two real people—scientists, presidents, soldiers, statesmen, mathematicians, artists—or two entities, concepts, or objects, such as geometric shapes, types of angles, chemicals, wars, historical documents, geological constructs, etc.

What is Poetry in Two Voices?

- In two-voice poems, poets write from two perspectives, comparing and contrasting.

- Similarities are written directly across from each other (or in a middle column) and read simultaneously

- Contrasting details are written on separate lines and read one at a time, in whichever order the author determines is more effective.

In English-Language Arts classes, readers-writers can compare and contrast two characters from the same text or from difference texts or themselves and a character from a text. In the content areas students can compare two real people—scientists, presidents, soldiers, statesmen, mathematicians, artists—or two entities, concepts, or objects, such as geometric shapes, types of angles, chemicals, wars, historical documents, geological constructs, etc.

Gradual-Release-of-Responsibility Lesson

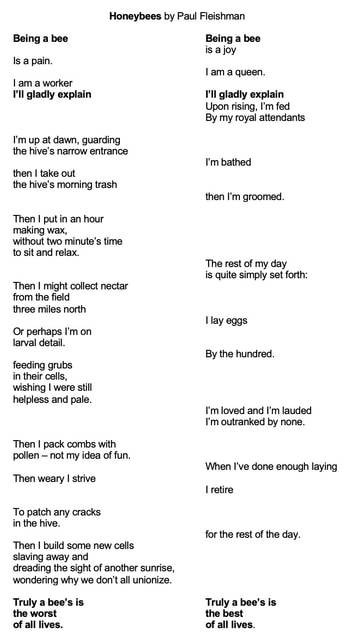

- Mentor Text: Teacher introduces Poetry in Two Voices with a mentor text. A colleague or a student always performed Paul Fleischman's "Honeybees" from Joyful Noises with me. The lines that are across from each other and in bold are read by both readers, simultaneously; the staggered lines are read individually by the appropriate reader.

2. Guided Practice:

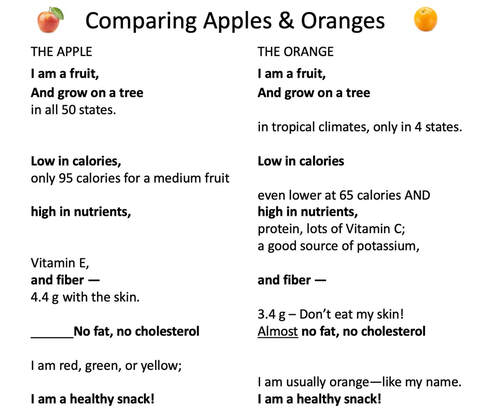

- I present facts about apples and oranges, and students as a class or in pairs write a Poem in Two Voices, "Comparing Apples & Oranges."

- Writers choose subtopics – color, geography, nutritional values,…

- Students look on the Fact Sheet provided for each item or conduct light research, if the teacher chooses.

- Students compare and contrast—they analyze similarities and differences and place in columns or a Venn diagram.

- Students draft a Poem in Two Voices, those of the items being compared, employing as many of the facts as they can.

- Writers write similarities across from each other to be read simultaneously

- Write differences on their own lines, to be read one at a time

- Writers write similarities across from each other to be read simultaneously

3. Independent Application:

- Individually or in pairs students choose two things from their curriculum or from a teacher handout of choices to compare and contrast.

- They brainstorm categories and facts and details.

- They each write a Poem in Two Voices.

- They perform with a partner for the class.

Rationale for writing Two-Voice Poetry:

When students compose poems in two voices based on material being read and learned, they are doing three things:

When students compose poems in two voices based on material being read and learned, they are doing three things:

- examining and analyzing similarities and differences

- reading from two perspectives

- going back to the text,* close reading, and reformulating the text into another genre. After students read a text, whether fiction or nonfiction, it is crucial to bring them back to the text so that they can learn. To learn, readers must interact with text—manipulating it, questioning it, re-thinking it, and synthesizing it—to store it.

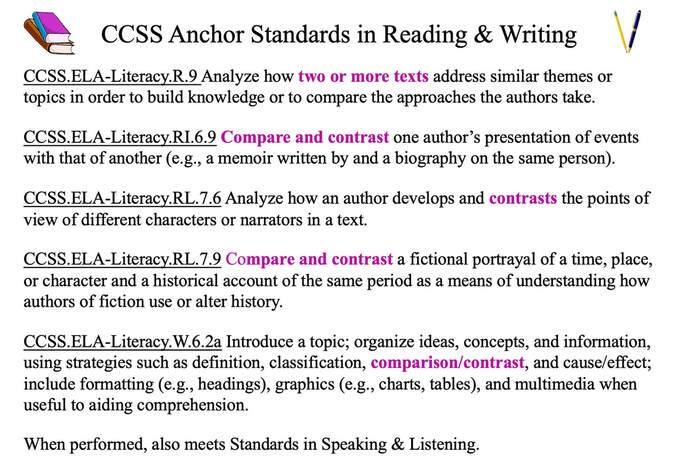

Meeting the Standards*: Writers can turn the poem into a prose-writing assignment, using the poems as a “prewrite,” especially to help reluctant writers gather ideas.

See lesson "Comparing and Contrasting with Cookies."

*Sample Standards met:

See lesson "Comparing and Contrasting with Cookies."

*Sample Standards met:

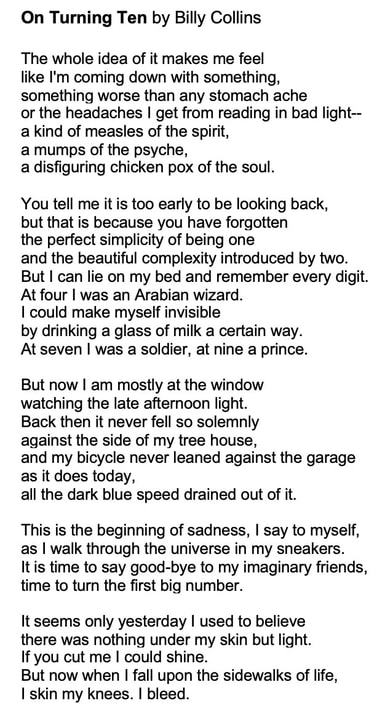

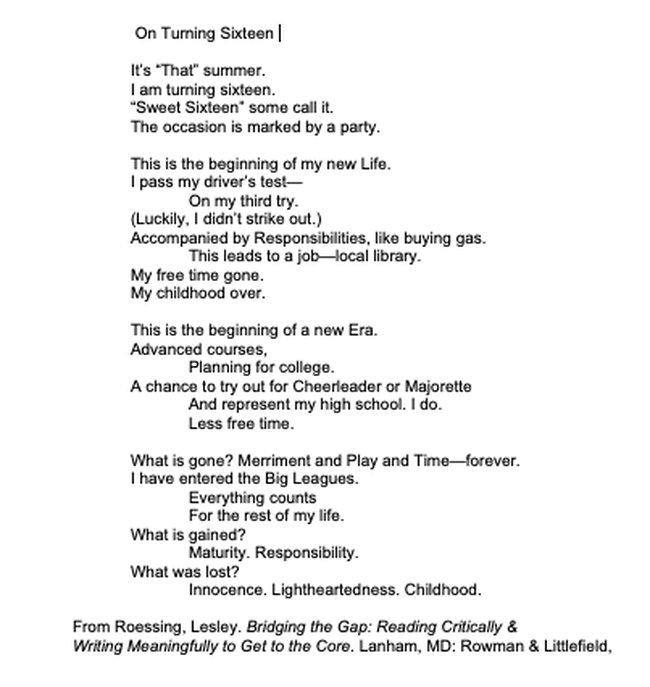

12. POETRY LESSON for READING & WRITING a MEMOIR of TIME

1. The teacher reads Billy Collins' poem "On Turning Ten." (mentor text)

1. The teacher reads Billy Collins' poem "On Turning Ten." (mentor text)

2. The class analyzes the poem (deconstruction).

3. Teacher and Writers individually create timelines of their lives.

4. Writers choose one year or one "time in their lives" and further brainstorm, adding details—people, places, and events.

5. Teacher shows their timeline and brainstorming and drafts their Teacher Model (reconstruction)

3. Teacher and Writers individually create timelines of their lives.

4. Writers choose one year or one "time in their lives" and further brainstorm, adding details—people, places, and events.

5. Teacher shows their timeline and brainstorming and drafts their Teacher Model (reconstruction)

6. Writers draft their own "On Turning _____" poem in free verse.

7. Writers revise their drafts based on a focus lesson, perhaps on adding details or including a poetic device such as internal

rhyme or figurative language.

8. For their final published draft, writers have the choice of format: poetry (rhyming or free verse), prose, or graphic.

The entire lesson, Collins' poem, a reproducible brainstorming form, my Teacher Model, student samples, and Standards addressed are included in Bridging the Gap: Reading Critically & Writing Meaningfully to Get to the Core, Ch 4 "Memoirs of Times & Ages."

Read more about "The Steps & Strategies for Teaching Writing," such as mentor texts, deconstruction and reconstruction, teacher models, revision lessons, etc. in my blog.

7. Writers revise their drafts based on a focus lesson, perhaps on adding details or including a poetic device such as internal

rhyme or figurative language.

8. For their final published draft, writers have the choice of format: poetry (rhyming or free verse), prose, or graphic.

The entire lesson, Collins' poem, a reproducible brainstorming form, my Teacher Model, student samples, and Standards addressed are included in Bridging the Gap: Reading Critically & Writing Meaningfully to Get to the Core, Ch 4 "Memoirs of Times & Ages."

Read more about "The Steps & Strategies for Teaching Writing," such as mentor texts, deconstruction and reconstruction, teacher models, revision lessons, etc. in my blog.

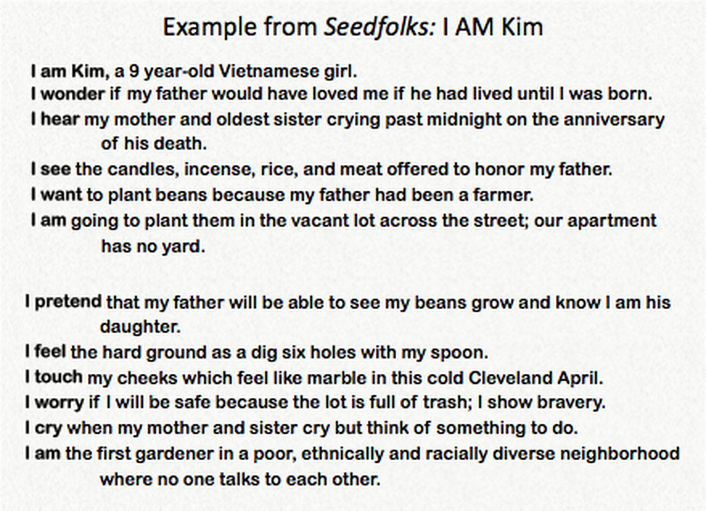

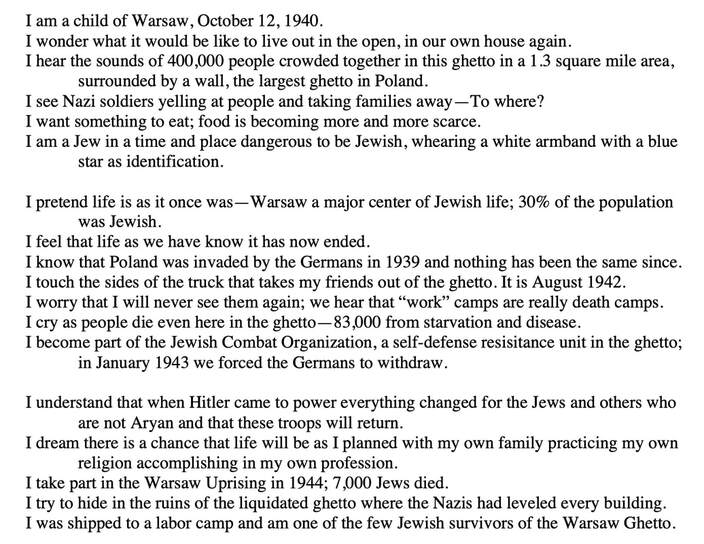

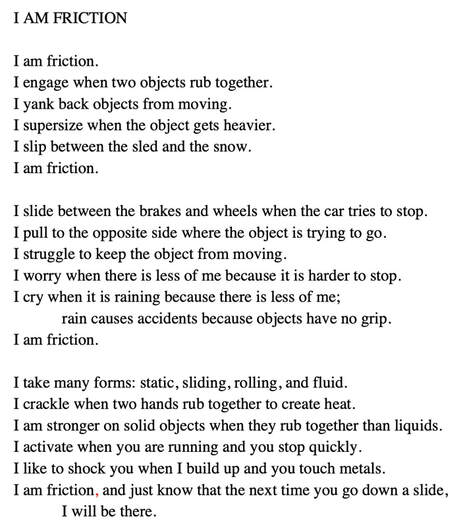

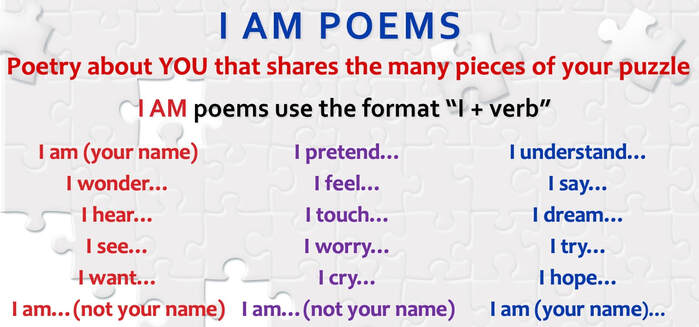

11. I AM POETRY to ANALYZE CHARACTERS & INCREASE COMPREHENSION

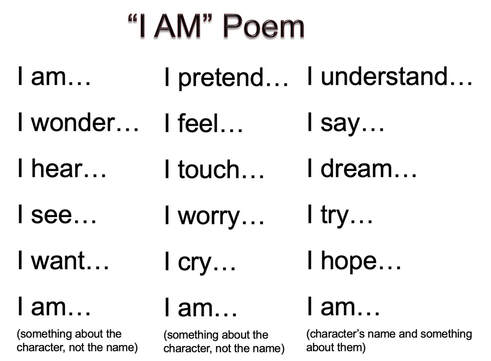

In “I Am” poetry, readers write from the perspective of something they have read in a text or textbook. They could be writing from the perspective of a character in a story or poem; a person from a memoir or biography; a scientist or a scientific theory, element, or concept; a person, event, or place in history; a mathematical concept or principle; or a disease, condition, or issue in health. The “I Am” poem follows a format that requires readers to read and analyze how a character or actual person—or even an item or event—in a text (narrative fiction/memoir/nonfiction) would view their world and their place in the world, returning to the text multiple times to apply what they have learned. This writing also causes readers to synthesize new material with information they already know or new information they may research to create their poem, thus increasing text comprehension.

There is a standard format readers/writers can follow (see figure below), but I encourage readers/writers to modify the verbs to fit their topic and their own visions. This format places the reader into another’s shoes, so to speak, and requires that they read more deeply, closely, and critically as they explore text from a particular point of view. (from The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension)

I Am poetry can be written in free verse or in rhyming stanzas, as the poet wishes.

In “I Am” poetry, readers write from the perspective of something they have read in a text or textbook. They could be writing from the perspective of a character in a story or poem; a person from a memoir or biography; a scientist or a scientific theory, element, or concept; a person, event, or place in history; a mathematical concept or principle; or a disease, condition, or issue in health. The “I Am” poem follows a format that requires readers to read and analyze how a character or actual person—or even an item or event—in a text (narrative fiction/memoir/nonfiction) would view their world and their place in the world, returning to the text multiple times to apply what they have learned. This writing also causes readers to synthesize new material with information they already know or new information they may research to create their poem, thus increasing text comprehension.

There is a standard format readers/writers can follow (see figure below), but I encourage readers/writers to modify the verbs to fit their topic and their own visions. This format places the reader into another’s shoes, so to speak, and requires that they read more deeply, closely, and critically as they explore text from a particular point of view. (from The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension)

I Am poetry can be written in free verse or in rhyming stanzas, as the poet wishes.

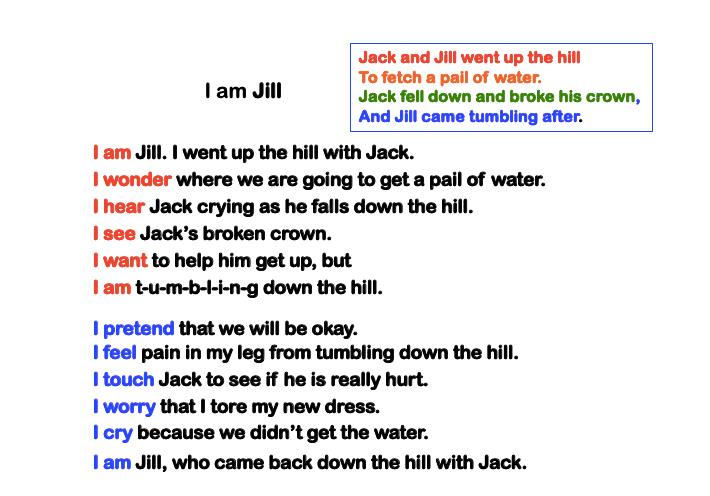

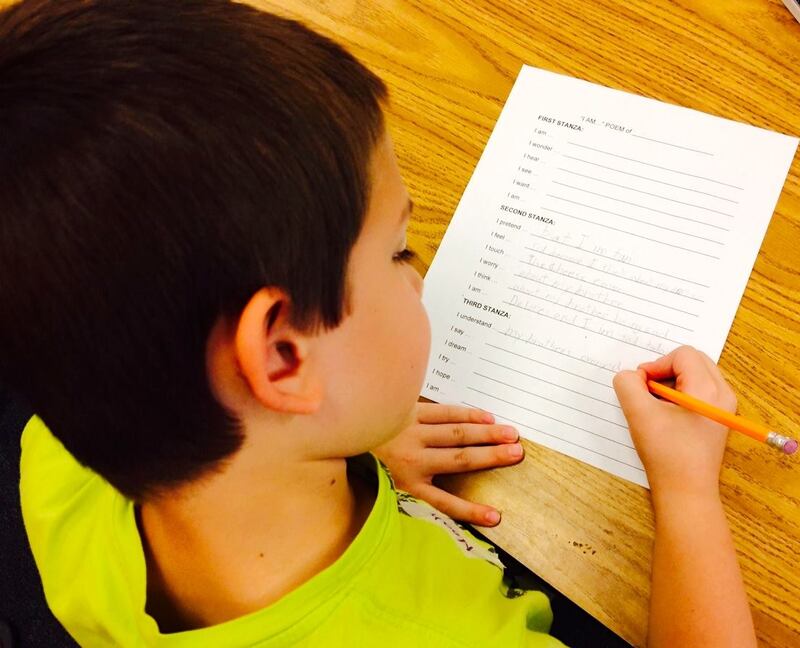

I worked with first graders on writing I AM poems about a character in a story.

- The students and I recited the nursery rhyme "Jack and Jill."

- I showed the I AM poetry format, and we talked about the verbs and what we might wonder, dream, and worry about, etc.

- I showed the teacher model that I wrote based on “Jack and Jill.”

- I read aloud Horace and Morris But Mostly Delores,

- The class collaborated on the first stanza of “I Am Delores.”

- They finished the last two stanzas individually or in pairs with some assistance from the teacher and me. [We looked at their lines and prompted…Teacher: "From what we read about her, would Delores really dream/worry about/pretend that?” Writer: "No, she probably wouldn't." Then they would think about what Delores did and said in the story a bit more and revise. ]

I employed the same strategies with older readers/writers in English-Language Arts and content areas, such as Science, social studies, and math but students could also read about and write as artists for art classes, etc. Their poems were expected to include more facts and details from their readings.

With secondary students who were reading Paul Fleischman's Seedfolks, I created an example from Kim's chapters as my teacher model. Readers then individually wrote I Am poems for the other characters and in order of their character's chapters, we read our poems aloud.

With secondary students who were reading Paul Fleischman's Seedfolks, I created an example from Kim's chapters as my teacher model. Readers then individually wrote I Am poems for the other characters and in order of their character's chapters, we read our poems aloud.

In a Social Studies class, we wrote I Am poems based on read and fictitious characters who experienced the events we studied. Here is a poem featuring a character created to show what we learned in our unit.

In 8th grade science class at the end of a unit, Ansleigh wrote "I Am FRICTION."

For more information and examples from advanced readers through grade 12, see the I Am Poetry section of my blog "The Benefits of After-Reading Response."

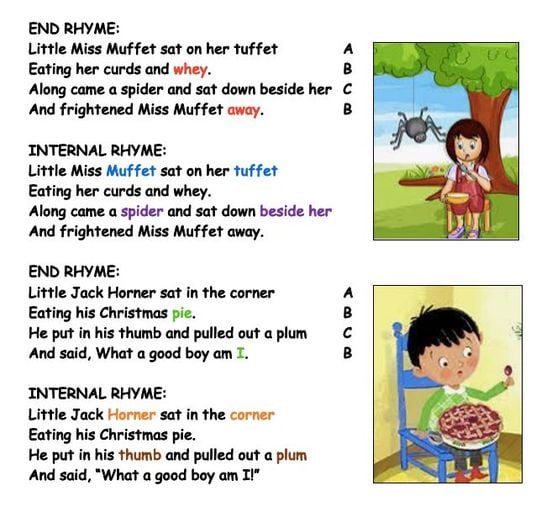

10. TEACHING END RHYME and INTERNAL RHYME

Day 1-2:

Using the same steps teach lessons on EYE RHYME (a similarity between words in spelling but not in pronunciation, i.e. rain/again) and SLANT RHYME or NEAR RHYME (a type of rhyme with words that have similar, but not identical sounds, i.e. crate/braid; yours/years; thumb/gun).

- Teach a focus lesson on END RHYME.

- Analyze a mentor poem that has a consistent end Rhyme Scheme (i.e., AABB). For older or more advanced classes, an example of a more sophisticated poem can be added or substituted

- In small groups the class composes poems with the same Rhyme Scheme (AABB).

- Analyze another mentor poem with a different End Rhyme scheme. (ABCB)

- In small groups the class composes poems with the same Rhyme Scheme (ABCB). For more advanced classes, add other end rhyme schemes , i.e., AABA—"Stopping By the Woods on a Snowy Evening" or ABAAB "The Road Not Taken."

- Each student chooses a rhyme scheme and writes a poem or, as a contest, pairs choose a rhyme scheme out of a bowl and compose a quatrain with that rhyme scheme. To make it more fun and quicker, add another bowl with topics, such as School Day and ABAB rhyme scheme.

- Teach a focus lesson on INTERNAL RHYME. Internal Rhyme is a rhyme involving a word in the middle of a line and another at the end of the line or a rhyme that occurs within a single line of verse.

- Follow the We Do-I Do procedure from the first day.

Using the same steps teach lessons on EYE RHYME (a similarity between words in spelling but not in pronunciation, i.e. rain/again) and SLANT RHYME or NEAR RHYME (a type of rhyme with words that have similar, but not identical sounds, i.e. crate/braid; yours/years; thumb/gun).

- deconstruct a mentor text

- whole class, group, pairs, draft a stanza including the poetic element

- individually, draft a short poem with __ stanzas.

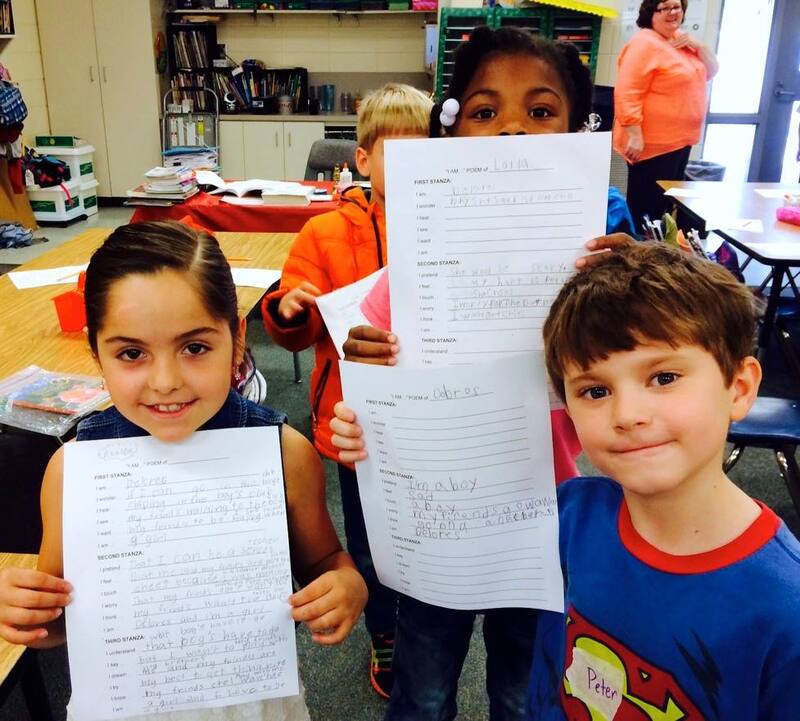

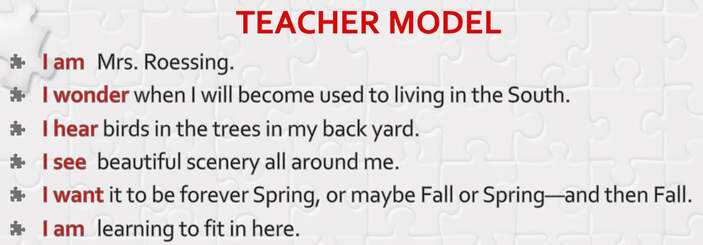

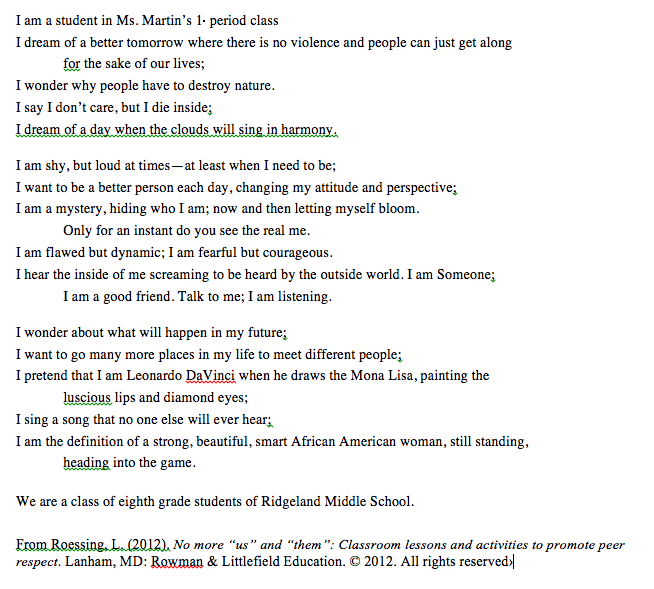

9. I AM POETRY for Building Classroom Community

"WE are a piece of the puzzle that is our class."

1. Teacher explains the I AM POETRY format which can be written in free verse or rhyming stanzas.

1. Teacher explains the I AM POETRY format which can be written in free verse or rhyming stanzas.

2. Teacher shares her model.

3. Students draft their poems

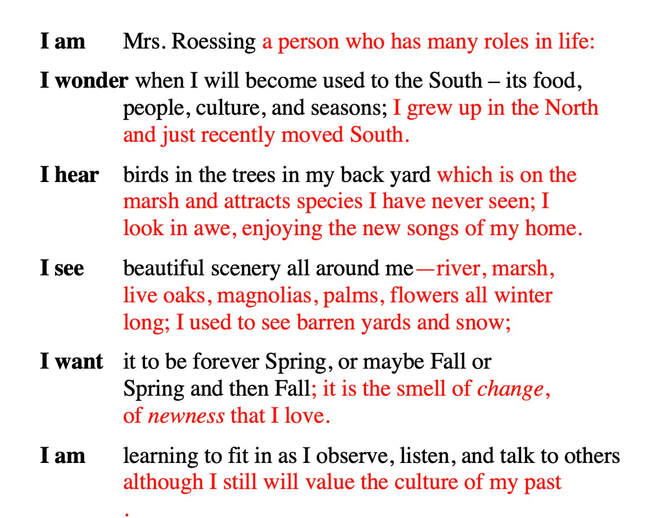

5. Teacher shares her revised model.

- Writers fill in the form with information about themselves, turning the list into poems.

- Writers are encouraged to change any of the verbs to ones that better suit them and their writing.

- Any who finish before classmates are encouraged to look over word choices. Did they say exactly what they wanted to say? POETRY is “the best words in the best order.”

5. Teacher shares her revised model.

6. Students revise their poems.

7. Teachers can also add a second or alternate Revision Focus Lesson for writers to add POETIC DEVICES/FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE that has been previously taught or can choose one to teach.

8. Students again revise their poems to add poetic device(s) taught.

7. Teachers can also add a second or alternate Revision Focus Lesson for writers to add POETIC DEVICES/FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE that has been previously taught or can choose one to teach.

8. Students again revise their poems to add poetic device(s) taught.

9. WE ARE…ALL PARTS OF THE PUZZLE Activity:

This lesson and two samples of a class WE ARE poem—grades 5 and 8—are included, along with more collaborative activities, in NO MORE "US" AND "THEM": Classroom Lessons & Activities to Promote Peer Respect, taking students from seeing similarities to valuing diversity to reaching respect.

- Writers are asked to put a star next to their favorite line or a line that they want to share with the class.

- Students stand in a circle around the room, a volunteer begins, and, going clockwise around the circle, each shares a line to create a class WE ARE poem.

This lesson and two samples of a class WE ARE poem—grades 5 and 8—are included, along with more collaborative activities, in NO MORE "US" AND "THEM": Classroom Lessons & Activities to Promote Peer Respect, taking students from seeing similarities to valuing diversity to reaching respect.

8. LIST POETRY

LIST POETRY is a good way to begin poetry with emerging writers, or all writers, of any age.

Have students write a LIST POEM of a place, object, person, or a topic they are studying. Teach through a Gradual-Release-of-Responsibility Writing Workshop Model: Reading a Mentor Text > Teacher Model (I Do) > Guided Practice (We Do) > Independent Application (I Do).

MENTOR TEXTS: For younger students I may use as a mentor text Nikki Giovanni’s “Knoxville, Tennessee”; for older students as a mentor text, I employ the simple structure but challenging text of two William Stafford poems, “What’s in My Journal” and/or “What I Learned Last Week.” A wonderful collection, by a variety of poets at diverse reading levels, is Georgia Heard's Falling Down the Page: A Book of List Poems.

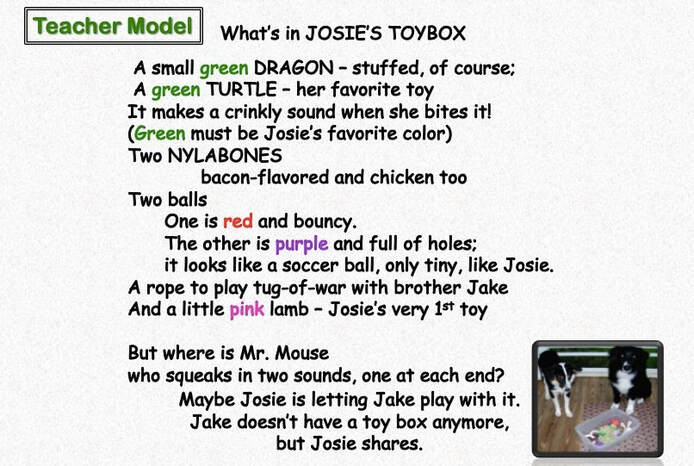

TEACHER MODEL:

For my teacher model when I work with elementary students, to construct the poem “What’s in Josie’s Toy Box.” (Josie is my Australian Shepherd):

1) I brainstorm a list of toys:

2) I invite student questions to add details (sights, sounds, smells, tactile), and I draft my poem.

A small green DRAGON – stuffed, of course;

A green TURTLE – her favorite toy

It makes a crinkly sound when she bites it!

(Green must be Josie’s favorite color)

Two NYLABONES,

bacon-flavored and chicken too

Two BALLS:

One is red and bouncy.

The other is purple and full of holes;

it looks like a soccer ball, only tiny, like Josie.

A rope to play tug-of-war with brother Jake

And a little pink lamb – Josie’s very 1st toy

But where is Mr. Mouse

who squeaks in two sounds, one at each end?

3) I add an ending:

Maybe Josie is letting Jake play with it.

Jake doesn’t have a toy box anymore,

but Josie shares.

4) I play with spacing and font color and size.

LIST POETRY is a good way to begin poetry with emerging writers, or all writers, of any age.

Have students write a LIST POEM of a place, object, person, or a topic they are studying. Teach through a Gradual-Release-of-Responsibility Writing Workshop Model: Reading a Mentor Text > Teacher Model (I Do) > Guided Practice (We Do) > Independent Application (I Do).

MENTOR TEXTS: For younger students I may use as a mentor text Nikki Giovanni’s “Knoxville, Tennessee”; for older students as a mentor text, I employ the simple structure but challenging text of two William Stafford poems, “What’s in My Journal” and/or “What I Learned Last Week.” A wonderful collection, by a variety of poets at diverse reading levels, is Georgia Heard's Falling Down the Page: A Book of List Poems.

TEACHER MODEL:

For my teacher model when I work with elementary students, to construct the poem “What’s in Josie’s Toy Box.” (Josie is my Australian Shepherd):

1) I brainstorm a list of toys:

- a small dragon'

- a turtle

- two Nylabones

- two balls

- a rope to play tug-of-war

- a little lamb

- Mr. Mouse, a stuffed squeaky toy

2) I invite student questions to add details (sights, sounds, smells, tactile), and I draft my poem.

A small green DRAGON – stuffed, of course;

A green TURTLE – her favorite toy

It makes a crinkly sound when she bites it!

(Green must be Josie’s favorite color)

Two NYLABONES,

bacon-flavored and chicken too

Two BALLS:

One is red and bouncy.

The other is purple and full of holes;

it looks like a soccer ball, only tiny, like Josie.

A rope to play tug-of-war with brother Jake

And a little pink lamb – Josie’s very 1st toy

But where is Mr. Mouse

who squeaks in two sounds, one at each end?

3) I add an ending:

Maybe Josie is letting Jake play with it.

Jake doesn’t have a toy box anymore,

but Josie shares.

4) I play with spacing and font color and size.

5) GUIDED PRACTICE:

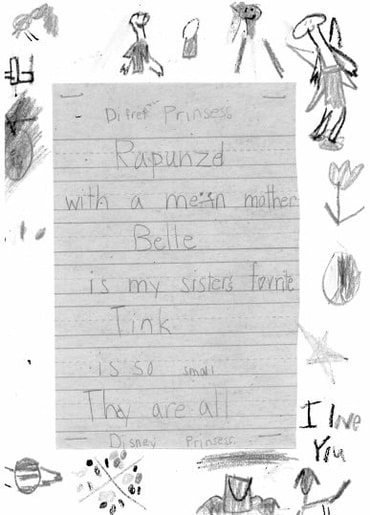

Students collaboratively make a list from a topic they are studying or reading about. They add details, maybe conducting some research. And add an ending (as a group or individually). These first graders (pictured) had been studying penguins. We made a list of what they knew and turned it into a poem, leaving spaces where they may add some research.

6) INDEPENDENT APPLICATION:

Writers individually brainstorm a topic (pairing for questions to add details) and write their own list poetry.

Poets drafted poems about "Disney Princesses," "What's Under My Bed," and "My Favorite Day."

>NOTE: With List Poetry, even these 1st grade Writers met two English-Language Arts Literacy standards:

•CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.1.2: Write informative/explanatory texts in which they name a topic, supply some facts about the topic, and provide some sense of closure.

•CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.1.5 With guidance and support from adults, focus on a topic, respond to questions and suggestions from peers, and add details to strengthen writing as needed.

Students collaboratively make a list from a topic they are studying or reading about. They add details, maybe conducting some research. And add an ending (as a group or individually). These first graders (pictured) had been studying penguins. We made a list of what they knew and turned it into a poem, leaving spaces where they may add some research.

6) INDEPENDENT APPLICATION:

Writers individually brainstorm a topic (pairing for questions to add details) and write their own list poetry.

Poets drafted poems about "Disney Princesses," "What's Under My Bed," and "My Favorite Day."

>NOTE: With List Poetry, even these 1st grade Writers met two English-Language Arts Literacy standards:

•CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.1.2: Write informative/explanatory texts in which they name a topic, supply some facts about the topic, and provide some sense of closure.

•CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.1.5 With guidance and support from adults, focus on a topic, respond to questions and suggestions from peers, and add details to strengthen writing as needed.

MEMOIR LIST POEMS, 8th grade examples, are included in BRIDGING THE GAP: Reading Critically & Writing Meaningfully, my book on memoir reading and writing.

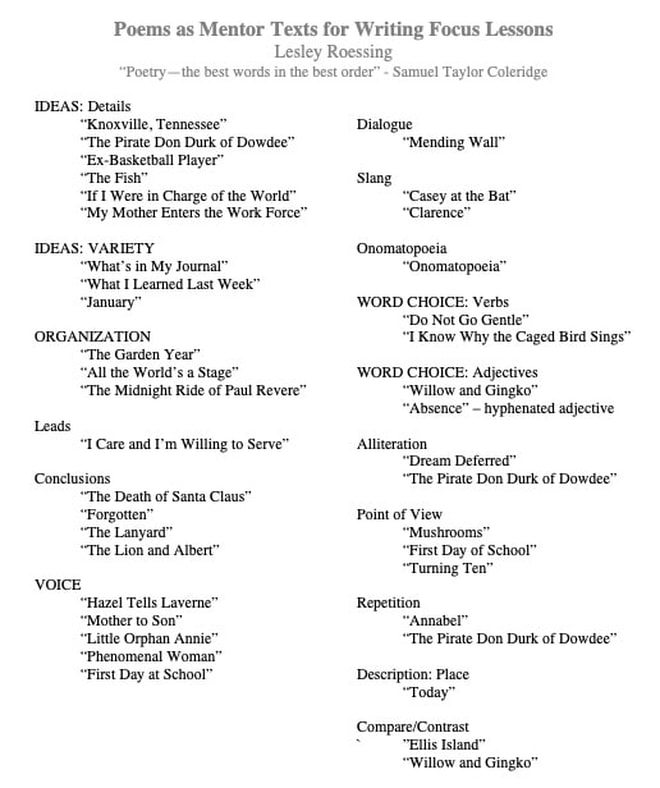

7. POETRY AS MENTOR TEXTS FOR WRITING

Many of us tend to use excerpts from novels, short stories, and picture books as mentor texts for Writing Workshop focus lessons, but what about poetry?

I collected poems in a binder and made a list of writing focus-lessons for which I could use each poem (or conversely, poems I could use for a focus lesson, as pictured). When I taught that lesson, I had my read-aloud and mentor text for my Teacher Model ready to go. I had a copy I could project for my Teacher Model or photocopy for students to mark for Guided Practice.

Different educators will see different poems as a fit for different lessons; here is an example of one of my lists. Find a poem you like and think, “What lesson(s) can I use this to teach?” [I also used poetry as mentor texts for Reading Workshop focus lessons]

Many of us tend to use excerpts from novels, short stories, and picture books as mentor texts for Writing Workshop focus lessons, but what about poetry?

I collected poems in a binder and made a list of writing focus-lessons for which I could use each poem (or conversely, poems I could use for a focus lesson, as pictured). When I taught that lesson, I had my read-aloud and mentor text for my Teacher Model ready to go. I had a copy I could project for my Teacher Model or photocopy for students to mark for Guided Practice.

Different educators will see different poems as a fit for different lessons; here is an example of one of my lists. Find a poem you like and think, “What lesson(s) can I use this to teach?” [I also used poetry as mentor texts for Reading Workshop focus lessons]

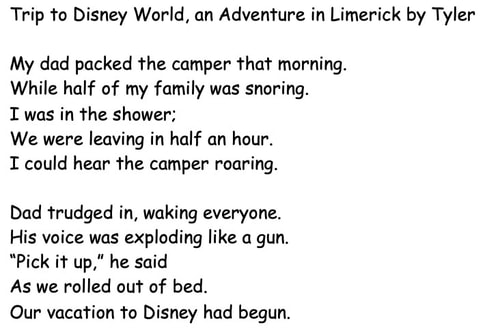

6. LIMERICKS TO TEACH RHYME SCHEME and RHYTHM

A limerick is a short humorous poem of five lines with the rhyme scheme AABBA and a specific rhythm that follows the rhyme scheme [think "Hickory, Dickory, Dock"]:

I found that students enjoyed writing limericks and then chose to do so in a variety of writing units––as long as the form fit the function.

As part of our our Memoir Unit, Tyler planned to write a memoir about his family trip to Disneyland. He decided to use the limerick format for the purpose of his poem, which was to entertain and illustrate the situation—that, as a teen, he now finds comical—to his audience which he identified as other eighth graders. Since a limerick would be too short, he wrote in limerick stanzas (Bridging the Gap: Reading Critically and Writing Meaningfully to Get to the Core). His first two stanzas:

A limerick is a short humorous poem of five lines with the rhyme scheme AABBA and a specific rhythm that follows the rhyme scheme [think "Hickory, Dickory, Dock"]:

- Line 1: la, LA, la, la, LA, la, la, LA (3 stressed beats)

- Line 2: la, LA, la, la, LA, la, la, LA (3 stressed beats)

- Line 3: la, LA, la, la, LA (2 stressed beats)

- Line 4: la, LA, la, la, LA (2 stressed beats)

- Line 5: la, LA, la, la, LA, la, la, LA (3 stressed beats)

I found that students enjoyed writing limericks and then chose to do so in a variety of writing units––as long as the form fit the function.

As part of our our Memoir Unit, Tyler planned to write a memoir about his family trip to Disneyland. He decided to use the limerick format for the purpose of his poem, which was to entertain and illustrate the situation—that, as a teen, he now finds comical—to his audience which he identified as other eighth graders. Since a limerick would be too short, he wrote in limerick stanzas (Bridging the Gap: Reading Critically and Writing Meaningfully to Get to the Core). His first two stanzas:

5. A FREE- VERSE POETRY LESSON

Free verse poetry is poetry that lacks

Free verse is not usually written in lines that are sentences; the line breaks add additional meaning.

This was my introductory lesson to free verse in preparation for reading free-verse novels:

Free verse poetry is poetry that lacks

- a consistent rhyme scheme

- metrical pattern (the rhythm of the words)

- and a consistent structure of stanzas although there may be a sound or rhythmic patterns within the poem.

Free verse is not usually written in lines that are sentences; the line breaks add additional meaning.

This was my introductory lesson to free verse in preparation for reading free-verse novels:

4. TEACHING ODES

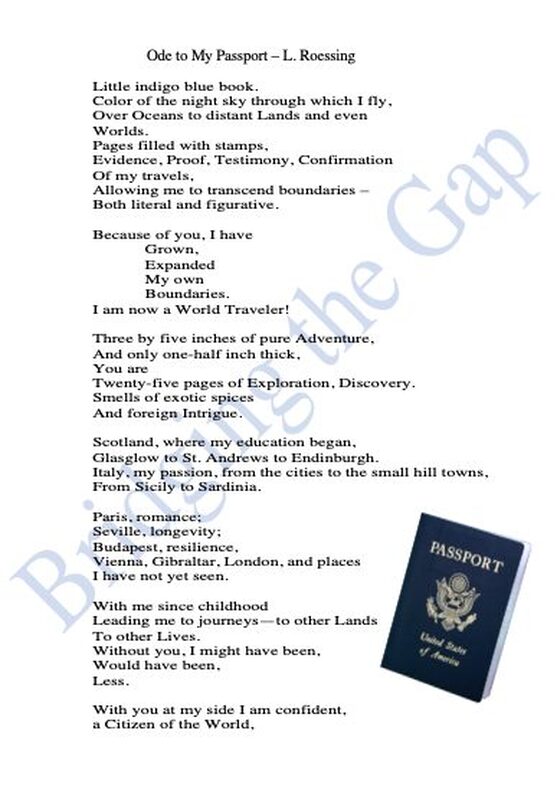

One goal of my memoir unit was to expose students to different types of writing (especially poetic forms) and have them attempt divergent types. When we wrote Memoirs about Mementos, I taught ODES which

One goal of my memoir unit was to expose students to different types of writing (especially poetic forms) and have them attempt divergent types. When we wrote Memoirs about Mementos, I taught ODES which

- focus on one object

- contain elaborate description

- are celebratory or even glorifying in tone

- I began the lesson with 2 mentor texts: Pablo Neruda's "Ode to Tomatoes" from Odes to the Common Things and Gary Soto’s “Ode to Pablo’s Tennis Shoes” from Neighborhood Odes.

- As a brainstorming activity we held a modified Show 'n Tell in groups of 4, each sharing our memento and 1-2 small-moment stories connected to it.

- Writers then brainstormed a list of descriptors for their objects.

- For my teacher model, I shared "Ode to my Passport" (from Bridging the Gap: Reading Critically & Writing Meaningfully to Get to the Core, which includes lessons, mentor texts, teacher models, and student samples for 8 different types of short memoirs written in prose, a variety of poetic forms, and graphics).

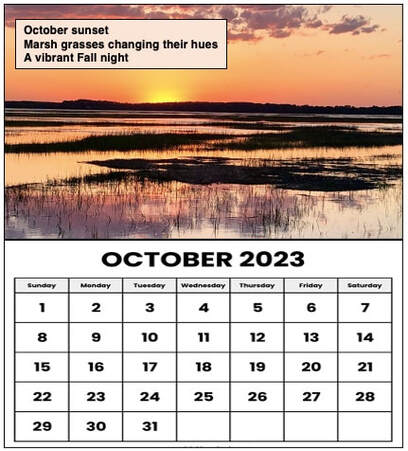

3. Creating HAIKU Calendars

The haiku is a Japanese poetic form that consists of 3 lines, with 5 syllables in the first line, 7 in the second, and 5 in the third.

Divide the class into 4 seasons, either 1 or 2 groups of 3 students per season.

Within groups, each student writes a haiku appropriate for one month within that season, ie., Fall Group will have a September haiku-writer, an October haiku-writer, and November haiku-writer.

Each student writes a haiku following the format and appropriate for the season. The poet finds or takes a photo or draws a picture that matches that month.

The class creates 1 or 2 different 2023 calendars with a picture and haiku for each month which can be copied and spiral-bound or sent in a pdf file to students to print and create calendars as gifts for family members, providing authentic audiences for their writing.

The haiku is a Japanese poetic form that consists of 3 lines, with 5 syllables in the first line, 7 in the second, and 5 in the third.

Divide the class into 4 seasons, either 1 or 2 groups of 3 students per season.

Within groups, each student writes a haiku appropriate for one month within that season, ie., Fall Group will have a September haiku-writer, an October haiku-writer, and November haiku-writer.

Each student writes a haiku following the format and appropriate for the season. The poet finds or takes a photo or draws a picture that matches that month.

The class creates 1 or 2 different 2023 calendars with a picture and haiku for each month which can be copied and spiral-bound or sent in a pdf file to students to print and create calendars as gifts for family members, providing authentic audiences for their writing.

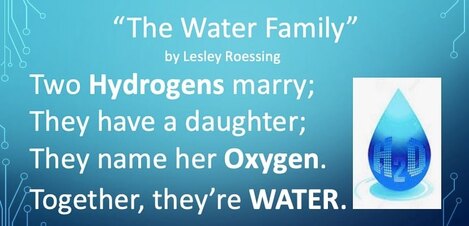

2. Learning Content through Writing Poetry

Students in any content area can create poems about the content which initiates engagement with the text, increases comprehension of material, and promotes learning. An activity such as writing poetry requires students to return to the textbook or their notes, or both for even more learning and to synthesize this learning by combining new learning with what they already know. Poetry also encourages students to write creatively and can produce high engagement.

Students can each choose one aspect of a topic to work on individually or in pairs and then present to the class. These presentations serve to demonstrate student learning and as a review of all material for the class.

I have designed this activity for ELA classes where small collaborative groups wrote raps based on acts Shakespeare’s Much Ado about Nothing or chapters in novels, in science classes where students wrote quatrains about the elements; in social studies students wrote I Am poetry about people affected by historic events. See more in my blog, “The Benefits of After-Reading Response” and in The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension.

Students can each choose one aspect of a topic to work on individually or in pairs and then present to the class. These presentations serve to demonstrate student learning and as a review of all material for the class.

I have designed this activity for ELA classes where small collaborative groups wrote raps based on acts Shakespeare’s Much Ado about Nothing or chapters in novels, in science classes where students wrote quatrains about the elements; in social studies students wrote I Am poetry about people affected by historic events. See more in my blog, “The Benefits of After-Reading Response” and in The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension.

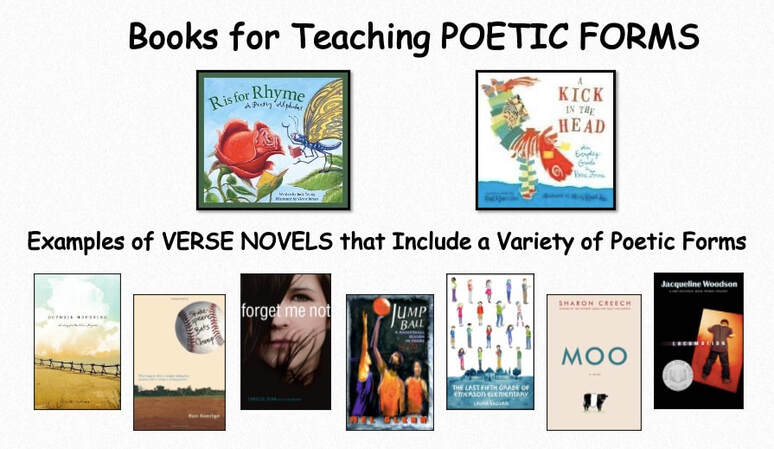

1. Teaching Poetic Forms through Verse Novels

Verse Novels are novels written in, more commonly, free verse; in other types of verse, such as Garvey’s Choice and the new Garvey in the Dark, written in tanka; or a in variety of verse types, as in Laura Shovan The Last Fifth Grade of Emerson Elementary. Verse novels that are written in a variety of poetic forms can be employed as mentor texts to teach writers these forms.

Pictured are two books I used to teach poetic form: R is for Rhyme: A Poetry Alphabet (We had multiple copies in my classroom for writers who wanted to experiment on their own during Writing Workshop) and A Kick in the Head: An Everyday Guide to Poetic Forms.

Reader-writers can also read multi-formatted verse novels as a class, in book clubs, or individually to learn a variety of poetic forms. For example, October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard shares a range of emotions through a wide variety of poetic styles: free verse, haiku, pantoum, concrete, rhymed, list, alphabet, villanelle, acrostic, and poems modeled after the poetry of other poets. In another example, Forget Me Not, author Carolee Dean creatively employs a variety of poetic forms—villanelle, pantoum, cinquain, tanka, shape poems—and meter, as well as script writing to identify the characters and alter the mood of the plot so subtly and artistically as to not disrupt the reading and the reader.

Verse Novels are novels written in, more commonly, free verse; in other types of verse, such as Garvey’s Choice and the new Garvey in the Dark, written in tanka; or a in variety of verse types, as in Laura Shovan The Last Fifth Grade of Emerson Elementary. Verse novels that are written in a variety of poetic forms can be employed as mentor texts to teach writers these forms.

Pictured are two books I used to teach poetic form: R is for Rhyme: A Poetry Alphabet (We had multiple copies in my classroom for writers who wanted to experiment on their own during Writing Workshop) and A Kick in the Head: An Everyday Guide to Poetic Forms.

Reader-writers can also read multi-formatted verse novels as a class, in book clubs, or individually to learn a variety of poetic forms. For example, October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard shares a range of emotions through a wide variety of poetic styles: free verse, haiku, pantoum, concrete, rhymed, list, alphabet, villanelle, acrostic, and poems modeled after the poetry of other poets. In another example, Forget Me Not, author Carolee Dean creatively employs a variety of poetic forms—villanelle, pantoum, cinquain, tanka, shape poems—and meter, as well as script writing to identify the characters and alter the mood of the plot so subtly and artistically as to not disrupt the reading and the reader.

See my recommendations and reviews of over 100 VERSE NOVELS.

Proudly powered by Weebly