- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

- Asian, Asian-American

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

"How wonderful it is that nobody need wait a single moment before starting to improve the world.” – Anne Frank

Youth change-makers do exist, on family, community, and global levels, although some of their names are more familiar than others.

Probably one of the most well-known, Malala Yousafzai, at age 17, became the youngest Nobel Peace Prize laureate in history from her work as a global advocate for girls' rights and education.

Working to save our planet are Greta Thunberg, Vanessa Nakate, Isra Hirsi, Xiuhtezcatl Roske-Martinez, and Jamie Margolin, teen climate change activists. Fionn Ferreira, a high school student, invented a new method of extracting microplastics from the water.

When Mohamad Al Jounde was 12, Mohamad escaped from Syria to Lebanon; after just six months, he worked with friends to set up a school for refugees, which has, since then, helped more than 7,000 pupils settle and integrate into their new country. Naomi Wadler is a 13-year-old activist on gun violence and discrimination against African American girls. And Salvador Gómez-Colón created the Light and Hope for Puerto Rico campaign to distribute solar-powered lamps and hand-powered washing machines when Hurricane María devastated Puerto Rico in 2017. David Hogg, Jaclyn Corin, Emma González, Cameron Kasky, and Alex Wind, students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, sparked the #NeverAgain movement for stricter gun regulation.

Many began at a very early age. Mari Copeny from age 8, when she wrote to president Obama, has worked for water access and to raise awareness for the Flint Water Crisis. She also works to bring resources to the children of Flint, Michigan. Melati and Isabel Wijsen, at ages 10 and 12, began the movement to ban all plastic bags in Bali; by the end of 2022, Bali plans to ban all single-use plastic. And at age 11, Marley Dias began working tirelessly for diverse representation in story.

Many of these names are unfamiliar to our youth who many times feel powerless, but stories of tweens and teens justice and change seekers, fictional and real, enable them see their how they can make a difference.

Youth change-makers do exist, on family, community, and global levels, although some of their names are more familiar than others.

Probably one of the most well-known, Malala Yousafzai, at age 17, became the youngest Nobel Peace Prize laureate in history from her work as a global advocate for girls' rights and education.

Working to save our planet are Greta Thunberg, Vanessa Nakate, Isra Hirsi, Xiuhtezcatl Roske-Martinez, and Jamie Margolin, teen climate change activists. Fionn Ferreira, a high school student, invented a new method of extracting microplastics from the water.

When Mohamad Al Jounde was 12, Mohamad escaped from Syria to Lebanon; after just six months, he worked with friends to set up a school for refugees, which has, since then, helped more than 7,000 pupils settle and integrate into their new country. Naomi Wadler is a 13-year-old activist on gun violence and discrimination against African American girls. And Salvador Gómez-Colón created the Light and Hope for Puerto Rico campaign to distribute solar-powered lamps and hand-powered washing machines when Hurricane María devastated Puerto Rico in 2017. David Hogg, Jaclyn Corin, Emma González, Cameron Kasky, and Alex Wind, students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, sparked the #NeverAgain movement for stricter gun regulation.

Many began at a very early age. Mari Copeny from age 8, when she wrote to president Obama, has worked for water access and to raise awareness for the Flint Water Crisis. She also works to bring resources to the children of Flint, Michigan. Melati and Isabel Wijsen, at ages 10 and 12, began the movement to ban all plastic bags in Bali; by the end of 2022, Bali plans to ban all single-use plastic. And at age 11, Marley Dias began working tirelessly for diverse representation in story.

Many of these names are unfamiliar to our youth who many times feel powerless, but stories of tweens and teens justice and change seekers, fictional and real, enable them see their how they can make a difference.

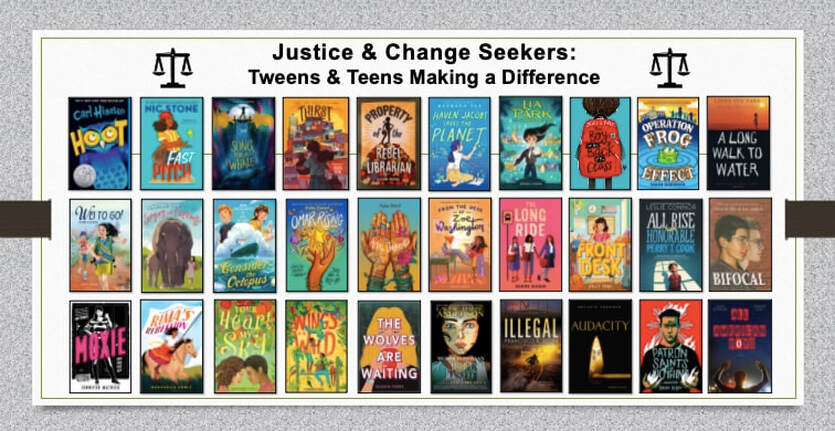

Pictured are 30 novels featuring characters who made a difference, a sampling of novels I have read in the past 5 years or so. My goal, as always in any thematic listing, is diversity in authors, characters, settings, reading level and interest levels, and format—prose, verse, and graphic. For others see my reviews of historical fiction novels (https://www.literacywithlesley.com/historical-fiction-book-reviews.html).

Below are reviews of 24 that I have read most recently.

----------

Amal Unbound by Aisha Saeed

It is immediately apparent why this novel was one of the books chosen for the 2018 #Global Read Aloud—well written, well-developed characters, strong adolescent female protagonist, and contemporary issues.

Twelve-year-old Amal lives in a rural Pakistani village where she is the eldest daughter of a small landowner, who like everyone else owes money to the greedy, corrupt landlord. She goes to school and dreams of becoming a teacher. After a run-in with the landlord’s son, she is required to work on the Khan estate to repay her father’s debt, an impossible feat since the servants are charged for lodging and food. As she becomes part of the household, connects with the other servants, and learns more about the unlawful Khan family, she has to decide how much to risk to save the villages, her friends, and her future. She is counseled by her new teacher, “You always have a choice. Making choices even when they scare you because you know it’s the right thing to do —that’s bravery.” (210)

I am adding Amal Unbound to my list of novels featuring my 4 guest blogs on Strong Girls in MG.YA literature. She reminds me of such adolescents as Serafina (Serafina’s Promise by Ann E. Burg) and Valli (No Ordinary Day by Deborah Ellis).

As author Aisha Saeed wrote in her Author’s Note, “Amal is a fictional character, but she represents countless other girls in Pakistan and around the world who take a stand against inequality and fight for justice in often unrecognized but important ways.” In this way novels and characters can function as maps to

----------

Audacity by Melanie Crowder

Clara Lemlich, a 23-year-old Ukrainian immigrant, rose to a position of power in the women's labor movement, becoming the voice that incited the famous Uprising of the Twenty Thousand in 1909. (PBS)

Audacity has become one of my all-time favorites historical novels and some of the best writing I have read. I usually choose books about more contemporary issues, but I am finding the same issues appearing throughout history, wearing different masks. Unfortunately oppression, intolerance, and treatment of refugees are not past, and we still need people unafraid to stand for their own rights and those of others.

Audacity relates the true story of Clara Lemlich, a Russian Jewish immigrant with dreams of an education who sacrifices everything to fight for better working conditions for women in the factories of Manhattan's Lower East Side in the early 1900's.

Lyrically related in verse, the use of parallelism and the purposeful placement of the words is as effective as the words themselves. A great mentor text for poetry study.

The novel includes the history behind the story and a glossary of terms. What a wonderful "text" for a social studies class!

----------

Consider the Octopus by Nora Raleigh Baskin and Gay Polisner

"Consider the octopus, dude, duh,” I say out loud to myself because sometimes it helps to talk to someone. “That part is the important part. The octopus.” (88)

And the pink octopus avatar starts the chain of events which lead 12-year-old Sydney Miller (not marine biologist Dr. Sydney Miller of the Monterey Bay Aquarium) and her goldfish Rachel Carson to Oceana II, a ship researching the Great PGP.

When seventh-grader Jeremy JB Barnes, under the custody of his recently-divorced mother, chief scientist of the Oceana II, finds himself accompanying her on her mission “to sweep and vacuum up approximately eighty-eight thousand tons of garbage” called the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, he was less than enthusiastic. “I like the ocean plenty from the beach.”

Until the high school SEAmester students arrive, he is the only adolescent on board. But tasked with the job of inviting well-known scientists to the join them, JB inadvertently sends the invitation to the wrong Sydney Miller who jumps at the chance, looking for something to do this summer now that her best and only friend has moved away. Sydney and her grandmother agree, “It’s synchronicity” (91), the simultaneous occurrence of events which appear significantly related but have no discernible causal connection. “What psychologist Carl Jung called ‘meaningful coincidences’…” (228) However, “These signs we see all the time, the universe, these coincidences that we give meaning? They only work if we want them to…” (12)

And Sydney and Jeremy want these signs to work. Hiding Sydney on the ship, sometimes in plain sight with the help of two of the SEAmster girls, Sydney and JB hatch a plan to bring about the publicity the mission needs to retains its grant. “Maybe we’re here because we’re supposed to be here. Maybe the two of us are supposed to do something really important.” (144)

When you put two of my favorite authors together, what do readers get? A fun, important adventure with engaging characters who present two voices, representing two perspectives, and who show that, according to news reporter Damian Jacks, “Mark my words: kids and our youth. That’s who’s going to really help change things..… Kids, not adults, are the future of our planet.” (171)

And there is a lot of science and information about the polluting of the oceans. “It’s amazing how many people still don’t know how much waste—garbage,” she corrects herself, “is floating in the middle of the Pacific.” (226)

Readers learn about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and its importance to our environment. Besides the garbage that is killing sea life—birds and fish, this affects all of us.

Because every drop of water we have, all of it, circles around, evaporates into the sky, and comes back down as rain, or mist, or snow. It sinks into the ground and fills rivers, ponds, lakes, reservoirs, and the well in my backyard.

Water I shower with. Cook with.

And drink.

No new water is ever made.

This is all we’ve got. (167)

An important read, this novel could be included in an environmental impacts study in ELA or science classes, leading to more research on the topic.

----------

Fast Pitch by Nic Stone

Twelve-year-old Shanice Lockwood is captain of a softball team, the Firebirds, the only all-Black softball team in the Dixie Youth Softball Association. She comes from a long line of batball players—her father, her grandfather PopPop, her great-grandfather. Her one goal is for her team to win the state championship.

But her goal shifts when she meets her Great-Great Uncle Jack, her Great-Grampy JonJon’s brother.

Shanice’s father had to quit baseball when he blew out his knee, his father had to stop playing to support his family, but why did JonJon quit when he was successfully playing for the Negro American League and was one of the first Black players recruited to the MLB? When Shanice is taken to Peachtree Hills Place to meet her sometimes-senile uncle, he tells her that JonJon “didn’t do what they said he did…He was framed.” (46) “My brother ain’t no thief. He didn’t do it…But I know who did.” (47)

And Shanice is off on a quest to research the incident that caused her great grandfather to leave baseball and to see if she, with Jack’s information and JonJon’s leather journal, can clear his name while still trying to lead her softball team to victory.

Fast Pitch is a fun new novel by Nic Stone, full of batball, adventure, a little mystery, peer and family relationships, Negro League history, prejudice, and maybe a first crush.

----------

From the Desk of Zoe Washington by Janae Marks

Statistics affecting our children:

All the lying was wrong. But maybe it was okay to do something wrong if you were doing it for the right reason. (180)

Zoe Washington, a rising 7th grader who loves baking and aspires to be the first Black winner of the “Kids Bake Challenge” and publish her own cookbook, is in a fight with her former best friend Trevor, and is not looking forward to a summer without him and her other best friends Jasmine and Maya. But her life changes when, on her 12th birthday, she receives a letter from Marcus, her biological father, a man who she has never met because he has been in prison from before her birth—for murder.

For the longest time, I didn’t care whether or not I knew my birth father. I had my parents, and they were all I needed. But [Marcus’] letters were making me feel that a part of me was missing, like a chunk of my heart. I was finally filling in that hole. (121)

Zoe decides to write back, and as she and Marcus exchange letters and music recommendations, she begins to suspect that he doesn’t seem like a murderer. He admits that he did not kill the victim and that there was an alibi witness whom his lawyer never contacted.

Since her mother has forbidden communication with Marcus (and has been confiscating his letters for years), Zoe confides in her grandmother who explains, “People look at someone like Marcus—a tall, strong, dark-skinned boy—and they make assumptions about him. Even if it isn’t right. The jury, the judge, the public, even his own lawyer‑they all assumed Marcus must be guilty because he’s Black. It’s all part of systemic racism.” (133)

Zoe researches the Innocence Project, and she and Trevor, friends again, go on a search for Marcus’ alibi witness in a plan to first prove to herself that Marcus is innocent and if so, to exonerate him.

This is a truly valuable story to begin important conversations about social justice and disparities.

----------

Front Desk by Kelly Yang

Ten-year-old Mia moves to the head of my “Strong Girls in MG/YA Lit” as she becomes an activist and champion of those who cannot, or will not, stand up for themselves [“You don’t get it, kid. I’ve been fighting my whole life. I’m done. It’s no use fighting—people are gonna be the way they’re gonna be” (105)], teaches others the wrongs of prejudice and injustice, and forms a community from her neighbors, patrons, and fellow immigrants.

Mia and her parents emigrated from China to the United States for a more “free” life. In China her parents were professionals; in America they feel lucky to find a job managing a motel. But the owner, Mr. Yao, is unkind, unjust, cheap, and prejudiced. He reduces their salaries until they are working for lodging and a life of poverty. And while this is a novel about Mia who manages the front desk and helps her parents temporarily hide other Chinese immigrants who have been mistreated, it is really a novel of culture, prejudice, bullying, community, and, most of all, the power of writing. “It was the most incredible feeling ever, knowing that something I wrote actually changed someone’s life.” (218)

In America there are two roller coasters, and people are born to a life on one or the other, but Mia and her friend Lupe, whose family came from Mexico, have decided to break that cycle. Although bullied in school and warned by her mother that she will never be a “native” English writer, Mia develops her writing skills to help Hank gain employment after a wrongful arrest, free “Uncle” Zhang whose ID and passport were being held by his employer, share her story with her teacher and classmates, and finally persuade friends and strangers to take a chance on her family.

Mia is a representative of the “nearly twenty million immigrant children currently living in the United States, 30 percent of whom are living at or below poverty.” (Author’s Note). As such, this book will serve as a mirror for many readers, a map for others looking for ways to navigate young adolescent life, especially in a new culture, and as a window for those who will learn empathy for others they may see as different. Author Kelly Yang also shares the autobiographical elements of the novel in her Author’s Note.

Front Desk, with its very short chapters and challenging topics would be a meaningful and effective 10-minute read-aloud to begin Grade 4-7 daily reading workshop focus lessons. I would suggest projecting Mia’s letters since they show her revisions as she seeks to improve her language skills and word choices.

----------

Haven Jacobs Saves the Planet by Barbara Dee

Although maybe we all had stuff in common with penguins. Maybe we were all standing on shrinking ice. Knowing it was shrinking and not knowing what to do about it. If there was even anything we could do at all. (15)

Eco-anxiety is defined as “extreme worry about current and future harm to the environment caused by human activity and climate change.” A new survey of 10,000 young people in 10 countries finds climate change causing widespread, deeply felt anxiety. (Medical News Today) More than 45% of young people in [the] survey said their feelings about climate change "negatively affected their daily life and functioning." (World Economic Forum)

Seventh grader Haven Jacobs suffers from “eco-anxiety.” She bites her nails, can’t sleep, and has stomach upsets. She also starts “doomscrolling,” endlessly watching videos about environmental disasters. Her grades in social studies, the class with her favorite teacher, suffer as she begins to find studying history pointless.

Haven is also having trouble with her friends, mostly her old friend Archer, her best friend Riley, and Riley’s new friend Em. I hadn’t told Archer how I felt about him avoiding me at school. I hadn’t told Em how I felt about the sleepover business. I hadn’t even told Riley how I felt about her telling me she’d left Em’s sleepover when actually she hadn’t. It was strange: I squabbled with Carter all the time, but sometimes when it came to my friends, I was kind of a wimp, wasn’t I? (97) Things start building as her eco-anxiety and friendship complications increase. Right then I had this feeling: I don’t understand anything. Not just what was happening with the river, but with people, too. I never used to feel this way, but now, all of a sudden, everything felt like a giant mystery, with no identification chart. (108)

When her science class embarks on the annual study of the town’s local river, Haven and her classmates discover that the river has changed a lot since her older brother’s class conducted the same study. There were no longer any frogs and the pollution-sensitive macroorganisms appear to have died. Their hypothesis is that someone is polluting the river, and the only new industry in Belmont is Gemba, her father’s employer.

One of the things [Ms. Packer] taught me this year is that if you can’t do great things, you should do small things greatly. (267) Haven organizes a river cleanup, but even though the whole town shows up, not many are come to her information booth to hear about the state of their river, and even though everyone participated in the river cleanup, they left as much trash on shore as they took from the river. Sensing the failure, Haven organizes a Memorial Day protest which turns into a sleepover (which actually does end up solving her friendship problems).

With the support of her older brother Carter, her parents, and her new friend Kenji, son of the glass plant manager, Haven overcomes her fear of public speaking and addresses the town council—with some results. Sometimes change was scary, like what was happening to the planet. But when it came to people—including older brothers—sometimes change could be kind of amazing. (257)

----------

Illegal by Fancisco Stork

Francisco’s Stork’s 2017 novel Disappeared takes place in Juarez, Mexico, and depicts sex trafficking, the cartel, murder, poverty, betrayal, abandonment.

Sara Zapata, a young reporter for a local paper, is committed to finding and saving the young women she learns are being kidnapped, including her best friend Linda, despite the warnings of her boss and the threats to herself and her family.

Sara’s younger brother Emiliano, whose life has been affected by his father’s abandonment—of the family and his native Mexico—is looking for a better life, for ways to make money to pay the family bills and win the love of his wealthy girlfriend.

The siblings find in following their consciences, helping others, and making moral choices, they need to do what is right—not what is easy or even safe, and must sacrifice, or revise, their personal goals. To save their lives, Sara and Emiliano escape to the United States to find a better life and to bring the cartel who is trafficking the women to justice. They cross the border and are attacked in the dessert.

Sara turns herself over to the authorities, certain that she meets the requirements for asylum but, as her time in the detention facility grows longer and she observes women being mistreated and deported for no reason, she questions her assumptions. I imagined that all I had to do was show the authorities the evidence of actual persecution, of actual threats, such as people machine-gunning our house in Juarez.… I saw my case as fitting within the legal reasons for asylum under the law of the United States. Was I wrong about the United States? (31) She finds that The whole process of who gets asylum and who gets detained, who gets a bond and who gets released, who gets a visa and who gets deported. I mean, it’s not as rational as I imagined it would be. (34)

Meanwhile Emiliano enters the country illegally and goes to Chicago with his father, planning to turn Linda’s evidence against the cartel over to the proper authorities. He also finds America to be less than welcoming. As he tells his new friend Aniela, “I think that in Mexico I feel like I belong all the time. I never feel not wanted like I do here sometimes. Here I’m always looking over my shoulder even when no one is there.…knowing that you belong and are wanted is major.” (251)

When Sara’s attorney is killed and she is placed in solitary confinement and Emiliano finds he can no longer trust his father, tensions escalate. A study of government corruption and the asylum process, this sequel to Disappeared is a thriller that will hook the most reluctant adolescent reader. Enough background is given in Illegal that it may not be completely necessary to read Disappeared first but it would surely enhance the reading.

----------

Lia Park and the Missing Jewel by Jenna Yoon

All I ever wanted was to be part of IMA, fight monsters, and be one of the four protectors of the world. (6)

Twelve-year old Lia is born in a world where magical powers count. And she has none—or at least none that she can identify. Her best friend Joon has magical powers and a chance to pass the exam for the International Magic Agency-sponsored school and become a great agent. Even Lia’s parents, her Umma and Appa, who are only desk agents, have “very low doses of magic.”

I turned twelve a few months ago. Normally, I was pretty good at Taekkyeon. But I couldn’t concentrate today. Feelings of dread welled up in the pit of my stomach. I knew how all this would end. Not well. (2)

So Lia decides she will stay at the normal school and become popular. I’d really thought that if I had no powers, I could still be somebody by being part of the popular group. (46) But when she defies her parents instructions and goes to the birthday party of Dior, her wealthy and most popular classmate, Lia unwittingly releases some magic, and all chaos is unleashed. She returns home to find her sitter Tina dead in the driveway and her parents kidnapped by the evil diviner Gaya.

Following her parents’ cryptic clues, Lia and Joon are transported to her Halmoni’s (grandmother’s) house in Korea where Lia learns her real family history and that “When you were born, your power had already manifested.… But it was dangerous, because the monsters sensed it too. That you were different.” (90)

Lia decides she has to make things right. All this was my fault.…It was because of me that my parents were kidnapped and were being held hostage by Gaya.”

What follows is edge-of-the-seat adventure that will keep readers reading and worrying and hoping as Lia follows clues and tries to find—and then secure—the jewel that Gaya demands and, using all her wits and spells, determines what to do to get back her parents (and Joon) without giving the power back to Gaya.

Readers will learn a bit about Korean culture and folklore as they race through this adventure with the newest superhero.

I have reviewed many novels where young adolescents show resilience and courage to “save the day,” sometimes for the adults in their families, but none are as fantastically spellbinding as Jenna Yoon’s Lia Park.

----------

Moxie by Jennifer Mathieu

“moxie”- force of character, determination, nerve.

Testosterone, football, and the football players run East Rockport High School in a small Texas town. All monies are funneled to the football team, and “Make me a sandwich” is the boys’ code for telling girls to stay in their place (even during classes). While girls are subject to humiliating dress code checks, football players get away with T-shirts displaying crude sexist rhetoric.

Good girl, don’t-rock-the-boat Vivian, the daughter of a feminist, at least in her own high school days, has had enough and, anonymously begins creating and posting vines from a group called “Moxie,” encouraging the high school girls to take action.

As some girls eagerly join the movement—bake and craft sales for the girls’ soccer team, protests of the Dress Code crackdowns, and labeling the lockers of boys who subject them to a Bump 'n' Grab “game," others are concerned about the ramifications of joining, and it is not until a rape attempt by the star football player, son of the principal—is disregarded that most of the high school girls—and a few boys—cross popularity and racial barriers and find their Moxie.

It occurs to me that this is what it means to be a feminist. Not a humanist or an equalist or whatever. But a feminist. It’s not a bad word. After today it might be my favorite word. Because really all it is is girls supporting each other and wanting to be treated like human beings in a world that’s always finding ways to tell them they’re not. (269).

Moxie is a must-read for high school students.

----------

Omar Rising by Aisha Saeed

What about the boys on the other side of the wall? Picking whatever activities they’d like because they were born into families who can pay their tuition. [The headmaster] is right. I’m lucky. But it’s hard to feel that way right now. (ARC, 50)

Omar lives in a one-room hut with his mother, a servant for the family of Omar’s best friend Amal. When Omar is accepted to the prestigious Ghalib Academy for Boys as a scholarship student, his whole town celebrates. He is aware that his future opportunities have widened, but he is particularly excited about the extracurricular activities, especially the astronomy club since he has always wanted to be an astronomer.

At school Omar immediately makes friends—Marwan and Jabril from Orientation; Kareem, his roommate and one of the scholarship kids along with Naveed, and soon others, especially when they observe Omar’s soccer skills. The only unfriendly person appears to be their neighbor Aiden. And Headmaster Moiz, the English teacher for the scholarship students or, as he says, “kids like you,” who appears to take an instant dislike to Omar. Despite having the academics to be accepted, the scholarship kids find the studies difficult, no matter how hard they study.

And then they find out that Scholar Boys are not permitted to join any activities or sports; instead they have to do hours of chores.

Back home, everyone was proud of me.

Back home, everyone was jostling for me to be part of their team.

But I’m not home now. (ARC, 56)

I’m the kid doing chores. Who can’t do any of the fun after-school activities. Struggling to keep up with my classes. (ARC, 153)

Omar and Naveed and the others fulfill their work hours, mainly in the kitchen with the chef Shauib and his son Basem where Omar finds he has some talent and where they can keep their secret from the other students (who think they are just nerds, studying all the time). Marwan acts like we think being stuck in a room on a Friday night instead of out having fun is what we want to do. He doesn’t get it. Because he can’t. (ARC, 109)

But the boys find out that the system is rigged. Most of the Scholar Boys are not expected to stay beyond the first year. Studying together with the other scholarship boys, night and day, Omar does well in science and math but continues to do poorly in English until he asks the Headmaster to tutor him.. “Finding out how hard it was to actually stay at this school, I’d started pushing away my dreams, afraid it would hurt more if it all crashed down. But maybe holding onto your dreams is how you make your way through.” (ARC, 117) He raises his grades but it is not enough; SBs are to maintain an A+.

For his art class final project, Omar studies Shehzil Maik, a local artist who works in many mediums to promote justice, equality, and resistance. With her influence, he designs his own collage, “Stubbornly Optimistic.” During his presentation Omar shares the injustice he and the other Scholar Boys are facing. We might go to the same school, but the rules are completely different for us.… We might be in the same classes but we are from different classes. (ARC, 176)

However, when the school unites to fight the discrimination, he finds that art can be a catalyst for change. This is a story of a young boy who is not only strong and resilient but one who is willing to make a difference for himself and future boys.

Note: This novel is a companion novel to Saeed’s Amal Unbound; even though a sequel in time, it can be read independently.

----------

Operation Frog Effect by Sarah Scheerger

When their teacher explains the Butterfly Effect, “It’s the idea that a small change in one thing can lead to big changes in other things…Anything and everything we do—positive or negative, big or small—can influence other people and the world.” (153, 155) and tasks her 5th graders to think about what they could do within their social-issues projects to make a difference, they do—with repercussions they did not imagine.

Told through their daily journals, readers learn about the lives and feelings of the eight students in Mrs. Graham’s classroom. Emily, whose two best friends have “outgrown” her, struggles through the year wondering if she will have friends again; when she is left to team with other students, she is upset but may have found newer, truer friends. Kayley is honest to a fault since she always knows best; she tells everyone, even the teacher, what is best and what to do, not afraid to burn bridges since she will be attending a private middle school next year. Aviva is caught in the middle. She still wants to be friends with Emily and do what’s right but is manipulated by what Kayley thinks. Sharon writes her journal in free verse; a typical loner, she hopes for letters in her desk mailbox as she slowly becomes part of a group of friends. Cecilia was born in America but addresses her journal entries to her Abuelita in Mexico, her mother coming to America for a better life for her child. Blake, who loses his home, draws his entries and turns out to be a tech whiz, while Henry writes his journal as scenes and makes jokes, slowly tearing down Kayley’s defenses. Kai, Taiwanese son of professors, is a voracious reader and wants to “be the kind of person who does something.” (230)

And Mrs. Graham is the teacher who forces them to think. When she tells them their first-day seats are their teams for the year, some students rebel but they slowly begin to perform and feel like teams, even friends. When Sharon has the idea that her team should experience a night of homelessness as “full immersion” in their social-issues project, serious consequences result, and it is up to the class to fix them—to make the big changes and influence their community. Named Operation Frog Effect in honor of the class frog they saved, the students learn to be part of a team and of a classroom community.

----------

Patron Saints of Nothing by Randy Ribay

There was a time I thought getting older meant you’d understand more about the world, but it turns out the exact opposite is true. (296)

Jason Reguero has his life planned out, at least as much as any typical 17-year-old. He will finish his senior year, play video games with his best friend Seth, attend Michigan in the Fall, graduate, and get a job, even though he has no idea what he wants to do and has not found anything that has awakened a passion .

In fact, Jay seems somewhat adrift until he receives the news that his seventeen-year-old cousin, Jun, was killed in the Philippines by government officials under President Duterte’s war on drugs, accused of being a drug addict and pusher. Jun’s father, as head of the police force, refuses a funeral or any type of memorial.

The last time Jay saw Jun was when his family, whose family had moved to the U.S. so the three siblings could be more “American” like their mother, was when they were ten and were like brothers. They had written back and forth until Jay got caught up in his own life and stopped answering Jun’s letters. Jun, questioning the political regime and the church, had moved from his restrictive father’s house and was thought to be living on the streets. Feeling guilty for having abandoned his cousin, Jay uses his Spring Break to fly to the Philippines to investigate Jun’s death, the reason he was really killed, and why no one—other than his sisters, Grace and Angel—mourns his death.

Jay is introduced to Grace’s friend Mia, a student reporter, and together they investigate Jun’s last few years. They find that Jun’s story is not that simple. “I was so close to feeling like I had Jun’s story nailed down. But no. That’s not how stories work, is it?. They are shifting things that re-form with each new telling, transform with each new teller. Less a solid, and more a liquid talking the shape of its container.” (281)

Ribay's coming-of-age novel, Jay finds some answers, and some more questions, challenging his preconceptions. But he also begins discovering his Filipino heritage and his identity as a Filipino-American. He finds a passion which determines his future—at least for now.

We all have the same intense ability to love running through us. It wasn’t only Jun. But for some reason, so many of us don’t use it like he did. We keep it hidden. We bury it until it becomes an underground river. We barely remember it’s there. Until it’s too far down to tap. (265)

This is a YA novel for mature readers about identity, family, heritage, and truth. Readers will also learn a lot about Filipino history and contemporary politics.

----------

Property of the Rebel Librarian by Allison Varnes

Censorship is a growing threat that infringes on our foundational rights. The year 2017 saw an increase in censorship attempts and a revitalized effort to remove books from communal shelves to avoid controversy. In 2017 the ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom tracked 354 challenges to library, school and university materials. Of the 416 books challenged or banned, the Top 10 Most Challenged Books were

promoting sex education, LGBT characters, sexual violence, violence, use of the N-word, and thought to “lead to terrorism” and “promote Islam.”

Many times when I read articles about books being banned in schools, particularly books such as the Harry Potter series, Charlotte’s Web, the dictionary, and ironically, Fahrenheit 451, I feel clueless. Can this happen? Why? Who is in charge of these bannings?

Well, in Allison Varnes new middle-grades novel, Property of the Rebel Librarian, I found those people—parents, PTSA members, school board members, administrators, those who we trust to educate our children, are the ones taking barrels of books out of the school library, leaving empty shelves.

It all started with one book. Seventh grader model student, band member, non-dater, and avid reader June Harper is relentlessly supervised by her parents. She and her college-student sister Kate are being groomed as future doctors, no preferences requested, no dating until age 16. But June is caught by her Dad reading a book called The Makings of a Witch. Not only was she reading the contraband, but the novel had been given to her by the school librarian. “It’s our job to protect you.” (4) The parents have the librarian suspended and institute a school library “book extraction for quality control.” The board passes resolutions prohibiting classroom use and independent reading of books containing “profanity, drugs, violence, rock/rap music, witchcraft, drinking, smoking, or rebellion of any kind.” And banning them from unsupervised distribution (59). Students are threatened with disciplinary action and teachers with termination.

Just when you think people cannot be more narrow-minded, June’s parents take every single book off her bedroom shelf. They plan to read every book and return only those deemed “quality reading material.” They eventually return some of the books, and, miraculously, Old Yeller has been cured and the other books have also had passages altered. Not only are books being banned but “appropriate” books have been censored.

One day on the way to school, having lost the people she thought were her friends, June discovers a LITTLE FREE LIBRARY. She takes a book and an idea is born. With her new friend Matt she begins a lending library of banned books from the empty locker next to hers, checking books out under Superhero names in her notebook “Property of the Rebel Librarian.” Now everyone in the underground knows her; she meets readers she never knew—the eighth-grade popular kids make up quite a surprising number. “Everywhere I look, kids line the hallways with oversized textbooks in their laps. At lunchtime and after school, their sneakers dangle off sidewalk benches. I don’t have to look to see what they are doing. I already know. Reading.” (119)

As she and her fellow readers take too many risks for their right to read and the library is discovered, a reporter asks June, “So if you could say one thing to America, what would that be?” Her reply, “Don’t tell me what to read.” (246)

This is a novel for all bibliophiles and those who question banning and believe in the right to read—starting with this book.

----------

Rima’s Rebellion by Margarita Engle

I dream of being legitimate

My father would love me,

society could accept me,

strangers might even admire

my short, simple first name

if it were followed

by two surnames

instead of

one. (53)

Twelve-year-old Rima Marin is a natural child, the illegitimate child of a father who will not acknowledge her.

I am a living, breathing secret.

Natural children aren’t supposed to exist.

Our names don’t appear on family trees,

our framed photos never rest affectionately

beside a father’s armchair, and when priests

write about us in official documents,

they follow the single surname of a mother

with the letters SOA,

meaning sin otro apellido,

so that anyone reading

will understand clearly

that without two last names

we have no legal right to money

for school uniforms, books, papers, pencils,

shelter,

or food. (11)

Rima, her Mama, and her abuela live in poverty, squatting in a small building owned by her wealthy father. Her mother is a lacemaker and her abulela—a nurse during the wars for independence from Spain—works as a farrier and founded La Mambisa Voting Club whose members are fighting for voting rights, equality for “natural children,” and the end of the Adultery Law which permits men to kill unfaithful wives and daughters along with their lovers.

Taking place from 1923 to 1936, Rima also joins La Mambisas; becomes friends with her acknowledged, wealthy half-sister, keeping her safe when she defies their father, refusing arranged marriage and becomes pregnant by her boyfriend; falls in love; and becomes trained as a typesetter, printing revolutionary books and posters for suffrage.

Over the thirteen years she grows from a girl who cowers from bullies who call her “bastarda,” finding confidence only in riding Ala, her buttermilk mare,

to an adolescent, living in the city and fighting dictatorship with words—hers and others:

absorb[ing] the strength of female hopes,

wondering if this is how it will be

someday

when women

can finally

vote. (43)

to a young married woman and mother voting in her first election:

Voting rights are our only

Pathway to freedom from fear. (167)

In this new novel of historical fiction, Rima joins author Margarita Engle’s other strong women, real and fictitious, in their fight for the people of Cuba—Liana of Your Heart My Sky; Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda or Tula, The Lightning Dreamer: Cuba's Greatest Abolitionist; Rosa of The Surrender Tree: Poems of Cuba’s Struggle for Freedom; and Paloma of Tropical Secrets: Holocaust Refugees in Cuba.

----------

Singing with Elephants by Margarita Engle

Poetry is a dance of words on the page. (1)

Poetry is like a planet…

Each word spins

orbits

twirls

and radiates

reflected starlight. (10)

“Poetry,”

she said,

“can be whatever you want it

to be.” (25)

And poetry is what connects a lonely girl with a new neighbor who turns out to be Gabriela Mistral, the first Latin American (and only Latin American woman) winner of a Nobel Prize in Literature.

Poetry also helps this young girl to find her words and her courage to face a grave injustice.

Oriol is an 11-year-old Cuban-born child whose veterinarian parents moved to Santa Barbara where

the girls at school

make fun of me for being

small

brownish

chubby

with curly black hair barely tamed

by a long braid…

…call me

zoo beast

…the boys call me

ugly

stupid

tongue-tied

because my accent gets stronger

when I’m nervous, like when

the teacher forces me to read

out loud (7-8)

Oriol’s friends are her animals and the animals she helps with in their clinic and on the neighboring wildlife zoo ranch. She learns veterinary terminology from her parents and poetry terms from her new friend.

When the elephant on the zoo ranch owned by a famous actor gives birth to twins and one is taken from her family by the actor and held captive, Oriol, with the help of her mentor, her family, and her new friends, fight to reunite the baby with her mother and twin.

Readers learn Spanish phrases and quite a lot about poetry, animal rights, Gabriela Mistral, xenophobia, and courage.

courage

is a dance of words

on paper

as graceful as an elephant

the size of love (99)

I read this beautiful book, a must for grade 3-8+ classrooms and libraries, in an afternoon. I feel it is Cuban-American poet, the national 2017-19 Young People’s Poet Laureate, Margarita Engle’s, best writing although I have enjoyed, learned from, reviewed, and recommended a great many of her verse novels. As part of a poetry unit or a social justice unit, Oriol’s story will speak to readers and help move them to passion and action.

----------

Song for a Whale by Lynne Kelly

This is a story of isolation and the need for connection and belonging.

Iris is twelve years old and deaf as was her grandfather—her closest ally—and her grandmother who is grieving her husband’s death and has isolated herself. At her school Iris is somewhat isolated as the only Deaf student. The only person she feels close to is her adult interpreter. The other students may try to include her in their conversations, especially an annoying girl who thinks she know sign language, but Iris gives up as she “tries “to grab any scrap of conversation” (64) and communicate better with her father.

In one of her classes Iris learns of Blue 55, a hybrid whale who sings at a level much higher than other whales and cannot communicate with any other whales. As a result he belongs to no pod and travels on his own, isolated. Iris decides to create and record a song that Blue 55 can hear and understand. “He keeps singing this song, and everything in the ocean swims by him, as if he’s not there. He thinks no one understands hi,. I want to let him know he is wrong about that.” (75)

Iris is a master at fixing old radios and feels without the storeowner for whom she fixes radios, she “wouldn’t know I was good at anything.” (68). With her knowledge of acoustics, Iris records a song at his own frequency for Blue 55, mixing in his song and the sounds of other sanctuary animals and sends it to the group in Alaska who are trying to track and tag him.

On a “run-away” cruise to Alaska, Iris and her grandmother reconnect; her grandmother makes new connections to others and finds a place she now needs to be; Iris connects with Blue 55 giving him a place to belong; and Iris is finally able to request to go to a new school that has a population of Deaf students with Wendell, her Deaf friend.

Scattered within the story are the heartbreaking short chapters narrated by Blue 55.

Readers will learn about whales, about acoustics, abut Deaf culture, and even more importantly, about those who may feel isolated and the need for belonging in this well-written new novel by Lynne Kelly, a sign language interpreter.

----------

The Boy at the Back of the Class by Onjali Q. Rauf

I read this darling, wonderful novel that deals with important issues—diversity, bullying, intolerance, and refugee children—in one day because I didn’t want to stop reading. I fell in love with the narrator right away, a British 9-year-old upstander.

A new student joins Alexa’s class, but he doesn’t talk to anyone, he disappears during every recess, and he has a woman who helps him with his work. And even though she has what some might term a challenging life herself—her father died when she was younger, her mum works two jobs to make ends meet and isn’t at home very much, and they have to be really careful about spending money, Alexa never sounds like she is complaining. Alexa and her three best friends, Josie, Tom, and Michael, a very diverse group of 9-year-olds, make it their mission to become friends with Ahmet. They give him gifts and then invite him to play soccer, where he excels, and they try to keep him safe from Bernard the Bully and his racist remarks and threats, which, it turns out, Ahmet can handle.

When they learn that Ahmet is a refugee from Syria, escaping on foot and in a lifeboat from bad people and bombs, the four friends are concerned. But when Alexa learns that his little sister died on the crossing and Ahmet does not know where his parents are and then learns from the news that the border is closing to refugees the next week, she puts a plan, the Greatest Idea in the World, in motion. She will ask the Queen to find Ahmet’s parents and keep the border open for them. When that plan seems to fail, the friends move on to the Emergency Plan.

I found it amazing that a novel on such a complicated subject could be handled so well and so thoroughly in a book for readers age 8-13. This book indeed will generate important conversations—and maybe some research and news article reading.

----------

The Long Ride by Maria Padian

You know, it’s a lot easier to be one side or the other. It’s harder to be in the middle. People don’t like the middle. That’s the bravest thing of all. (178)

Jamila, Josie, and Francesca are best friends of mixed race in 1971 Queens, NY. Their plans for starting seventh grade with each other and their white schoolmates at the neighborhood junior high school change when they become part of social experiment—integration. Francesca’s parents send her to a private school where she doesn’t fit, while Josie and Jamila take a long bus ride to a predominately black school in a much rougher neighborhood. They hope they may fit in better there, but Jamila is too white for the girls and Josie is no longer in the advanced classes and worries about her future. The girls don’t fit into their new school neighborhood and their new friends don’t fit into their neighborhood.

As they try to navigate seventh grade, boyfriends, teachers, classes, narrator Jamila’s anger, and Josie’s shyness, Jamilla realizes, “if anyone had told me this was what being in junior high would be like: Your best friend is silent beside you. You’re skinny and knock-kneed and you get lost easily. You aren’t at the top of the Ferris Wheel. I’d have said: You can have it. (60)

The world seemed to have changed. …I’m starting to notice that something bigger s going on in the city. Everyone is edgier, angry. You can feel it in the way people squint through the bus windows.

----------

The Wolves Are Waiting by Natasha Friend

Nora Melchionda was a typical high school girl. She played a sport, earned good grades, wore fashionable clothes, and had a group of friends, an older brother and a younger sister. Her father was Athletic Director of Faber, the local college, and her hero.

Then one night Nora attends the college frat fair, a fundraiser for the fraternities. And she wakes up on the golf course, surrounded by her former best friend and Adam Xu, a boy from school. The last thing she remembers is someone handing her a root beer. Adam explains how he was practicing his baseball hitting, found her, and chased off the three boys who, most likely, had roofied her and were planning to rape her, and called Cam.

“They took off her clothes, and they wrote on her body, and they hung her underwear on a stick like some kind of trophy.” (139)

Nora wants to forget what happened. “It didn’t happen to you. It happened to me. And if I say it’s over, it’s over.” (50), but Adam and Cam are determined to investigate and find out who the boys were and what exactly happened, especially when they begin hearing of other stories by young women of the college and the town. “Help me find out who they are,” [Cam] said. “Please. Before they do it to someone else.” (110)

Through technology and good legwork, they trace the young men to Alpha Phi Beta, the Faber fraternity for athletes, Nora’s father’s fraternity, and discover that what happened to Nora was part of a pledge game.

The story is told in alternating chapters narrated from the perspective of Nora, Cam, Adam Xu, and Asher, Nora’s older brother, a well-meaning high school senior who learns a lesson himself. “You tried to tell me. ‘When you wear things that are too short’—she shook her finger and made her voice deep—‘guys think it’s an invitation.’” He shook his head. ‘I said some guys. I didn’t mean—.’”(139)

With her new supporters and her mother and younger sister, Nora decides she has the strength to make a difference and end this sexual harassment and abuse.

An important, even vital, well-told story for adolescent girls—and especially—boys, Natasha Friend’s newest novel joins a too-small group of other novels about this crucial topic. Assaults among people under the age of 18 are common: 18% of girls and 3% of boys say that by age 17 they have been victims of a sexual assault or abuse at the hands of another adolescent (theconversation.com). Females ages 16-19 are 4 times more likely than the general population to be victims of rape, attempted rape, or sexual assault. Among undergraduate students, 26.4% of females and 6.8% of males experience rape or sexual assault through physical force, violence, or incapacitation. These statistics are incomplete as only 20% of female student victims, age 18-24, report to law enforcement. (RAINN.org).

----------

Thirst by Varsha Bajaj

Over and over she chants, like it’s a mantra. “You’re not alone. You’re very brave.”

And slowly I begin to believe [Shanti]. (61)

Minni lives in Mumbai in an area of extreme poverty with little access to water. She goes to school, trying to graduate and make a better life, while her mother gathers water, cooks for the family, and works as a maid for a wealthy family. Her father works long hours at his tea stand, and her brother had to drop out of school and cuts vegetables in a restaurant, dreaming of becoming a chef. The people in her area wait long hours in line every morning for water which then has to be boiled to be safe.

One night Minni, her brother Sanjay, his friend Amit, and Minni’s best friend witness water being stolen by members of the Water Mafia, men who then sell it to the rich. Sanjay and Amit are seen by the thieves and have to leave town. Then Minni’s mother becomes ill and goes to stay with family who can care for her, and Minni has to balance getting and boiling the morning water, trying to arrive at school on time so she won’t be locked out, her studies, cooking for her father and herself, and covering her mother’s job working for Anita Ma’am, her daughter Pinky also a 12-year-old, and Pinky’s father mother who demeans and insults Minni.

Besides her best friend Faiza, many community members have faith in and support Minni. As she writes in her journal,

Your family is always part of you,

In your blood and in your memories.

Your true friends are with you too.

They hold you in their hearts and walk besides you.

So that even the days you walk by yourself,

You’re not alone. (78)

Minni wins a coveted scholarship to a Sunday computer class where the American instructor becomes yet another ally and where she works to design an app that might help with the time her community members lose standing in water lines each morning.

When working at Pinky’s lavish apartment, she notices,

Water flows through the taps in Pinky’s bathroom.

The tap doesn’t need s marigold garland wrapped around it.

Money, not prayers, makes the water flow. (73)

And when she recognizes the man in charge of the water theft, she knows she has to do something to stop the stealing of water.

The next day doubts fill my head. Why do I think I can change anything? Who am I? A mere twelve-year-old girl who is struggling to pass seventh grade. Whose family is just scraping by in this city of millions. Then I remember all the fights I’ve witnessed in the water lines.

When there’s not enough water to go around, there’s anger fear, and frustration.…I can’t back away. I have to act, to do somethings. (155)

----------

Wei to Go by Lee Y. Miao

A runner, a home-run wannabe, and a lacrosse trainee get off a subway exit in Kowloon. (227) No, this is not the opening line of a joke. It actually is the middle of an adventure starring Elizabeth Wei Pettit, Kipp Wei Pettit, and their mother.

When she finds out that the design firm her father founded is about to face a corporate takeover by the Black Turtle Group based in Hong Kong and her family would have to move away from her bestie, her maybe-crush, and her softball team (before finally getting a wristband for her first homerun), Ellie decides to save Avabrand. She talks her mother into accepting a trip to Hong Kong won in a contest—and take her along. Unfortunately, her annoying younger sports-minded brother also has to go, but, on the positive side, he is a human GPS, and navigation is definitely not Ellie’s strong point. One family and two kids with one middle name. Three months before seventh grade and I’m traveling across the Pacific to save my dad’s company. With my little brother—ugh! (45)

After many cryptic clues, dead ends, and sharp turns involving two brothers—Mr. Han (Ellie’s Chinese heritage teacher in the U.S.) and Gerard (BT’s CEO), and a lot of resilience lead to a face-off and hopefully a win:

I straighten myself up. I can go for it.

My family will not be kicked off our front porch.

I will stay in my school.

I will stay in my home.

Kipp will stay on his lacrosse team when he makes it.

Mom will stay with her job.

Dad will stay with his company. (268)

There is another positive side to the trip. When I found out the world is bigger than my family and me, I didn’t know I’d literally be running around in a new place far from home. (271)

Asian-American Ellie and the readers learn a lot about Hong Kong, Chinese culture, sports, the business world, and the support of other people. I had lots of help. [Mr. Han] nudged me at first. I had Kipp and Mom. I thought about things that Dad, my softball coach, my English teacher, and my bestie said to me. Even my next-door neighbor and her two little boys. They were all with me at different times. (269)

----------

Wings in the Wild by Margarita Engle

2018: Teen refugees from two different worlds. Soleida, the bird girl, is fleeing an oppressive Cuban government who has arrested her parents, protesters of artistic liberty, their hidden chained-bird sculptures exposed during a hurricane; she is stranded in a refugee camp in Costa Rica after walking thousands of miles toward freedom. Dariel is fleeing from a life in California where he plays music that communicates with wild animals but also where he and his famous parents are followed by paparazzi and his life is planned out, complete with Ivy League university. When a wildfire burns his fingertips, he decides to go with his Cuban Abuelo to interview los Cubanos de Costa Rica for his book. And then he decides to stay to study the environment.

When Soleida and Dariel meet, he helps her feel joy—and the right to feel joy—again, and they fall in love, combining their shared passions for art and music, artistic freedom, and eco-activism into a human rights and freedom-of-expression campaign to save Soleida’s parents and other Cuban artists and to save the endangered wildlife and the forests through a reforestation project. This soulful story, beautifully and lyrically written by the 2017-19 Poetry Foundation's Young People's Poet Laureate Margarita Engle is not as much a story of romance but of a combined calling to save the planet and the soul of the people—art. Soleida and Dariel join my Tween and Teen Justice & Change Seekers whose stories are reviewed in https://www.literacywithlesley.com/justice--change-seekers.html.

Wings in the Wild also reintroduces two of my favorite characters, Liana and Amado [search my review of Your Heart—My Sky], who “became local heroes by teaching everyone how to farm during the island’s most tragic time of hunger.” (5) This is the 10th Margarita Engle verse novel (and memoirs) that I have read and recommended and from which I have learned about Cuban history.

------------------

Wonder Woman: Tempest Tossed by Laurie Halse Anderson

Wonder Woman is the most popular female comic-book superhero of all time. In 1941she emerged, the creation of lawyer-psychologist-professor William Marston, fully formed as an adult to chronicle the growth in the power of women. Readers of DC comics knew her as Princess Diana of Themyscira but how did she become the symbol of truth, justice and equality.

Author Laurie Halse Anderson, somewhat of a Wonder Woman herself, a woman of strength, compassion, and empathy, approachable and full of warmth, speaking truths and working for justice, was the perfect person to bring Wonder Woman to life. In Tempest Tossed she teamed with artist Leila del Duca to fill in the adolescent years of Diana, tossed from her homeland on her 16th birthday as she tries to save refugees, becoming a refugee herself exiled in America. In her new homeland, she finds danger and injustice and joins those who fight to make a difference.

Tempest Tossed shows the strength of women but most of all the power adolescents can wield when they find their purpose.

----------

Your Heart—My Sky: Love in the Time of Hunger by Margarita Engle

I began learning about the history of Cuba through Cuban-American poet Margarita Engle’s memoir, Enchanted Sky. I continued my study, learning more Cuban history through the stories of Tula, The Lightning Dreamer: Cuba’s Greatest Abolitionist; though the story of Rosa in The Surrender Tree: Poems Of Cuba’s Struggle For Freedom; with Daniel, one of the Holocaust refugees in Cuba in Tropical Secrets; and the story of Fefa (based on Engle’s grandmother) in The Wild Book. But there is still more history to learn.

Your Heart—My Sky: Love in The Time of Hunger introduced me to a different, more contemporary era, “el period especial en tiempos de paz.” The government’s name for the 1990s is “the special period in times of peace,” but in reality is a period of extreme hunger resulting from the loss of Soviet aid, the US trade embargo, and the government prohibition of the growing, buying, and selling of agricultural products. Even though the 1991 Pan Am Games are being held in Havana, where visitors and athletes are sure to find food, the people in the towns face starvation, their food rations reduced even more.

No witnesses.

We are like an outer isle

Off the shore of another island.

Forgotten. (3)

My parents quietly call it tourist apartheid.

Everything for outsiders.

Nothing for islanders. (Liana, 6)

Readers are introduced to the disastrous effects of these policies on the citizens through the three narrators: Liana, Amado, and the Singing Dog who serves as a matchmaker between, and a guard of, the two adolescents.

Liana and Amado are both rebels in their own ways: Liana skips la escuela al campo “a summer of forced so-called-volunteer farm labor,” possibly giving up college or a government-assigned tolerable job, spending her days looking for food. Amado has made a pact with his brother who is in jail for speaking against the government. He is worried that he won’t be able to keep his promise to avoid the mandatory military service—“men have to serve in the reserves until they’re fifty”—and promote peace, possibly joining his brother in prison.

Maybe I should let myself be trained to kill,

become a soldier, gun-wielding, violent,

a dangerous stranger, no longer

me. (Amado, 24)

In beautiful lyrical verse, lines that caused me to re-read and savor, Liana and Amado meet and fall in love,

The pulse in my mind wanders away

From hunger, toward something I can barely name.

A spark

of wishlight

on the dark horizon’s

oceanic warmth. (Liana, 35)

Liana meets Amado’s grandparents who are growing vegetables and fruits in hidden gardens, and she is given seeds to start her own gardens. She dreams of starting a kitchen restaurant.

Everything has changed inside our minds

So that we are intensely aware of our ability

To seize control of hunger,

Transforming food

Into freedom. (110)

Amado and Liana help fleeing refugees, even though

Leaving the island is forbidden by law

And it is equally illegal

To know that someone is planning to flee. (95)

When Amado receives a note from his brother releasing him from their pact, he secretly plans their rafting escape. But the indecision brought about by the precariousness of the trip cause them to reconsider.

All we have in our shared hearts

is one imaginary raft--

How shall we use it?

Climb aboard or set it loose,

Let that alternate future

drift away? (Liana and Amado, 197)

A beautiful story of a terrible time in Cuban history and two resilient families connected by love (and a singing dog).

---------------

For lessons and strategies to group and read these novels in Book Clubs where readers can work together, see Talking Texts: A Teacher’s Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum.

See other reviews of recently published, read, and recommended novels by topics for Grades 4-12 in the drop-down menu under BOOK REVIEWS.

Below are reviews of 24 that I have read most recently.

----------

Amal Unbound by Aisha Saeed

It is immediately apparent why this novel was one of the books chosen for the 2018 #Global Read Aloud—well written, well-developed characters, strong adolescent female protagonist, and contemporary issues.

Twelve-year-old Amal lives in a rural Pakistani village where she is the eldest daughter of a small landowner, who like everyone else owes money to the greedy, corrupt landlord. She goes to school and dreams of becoming a teacher. After a run-in with the landlord’s son, she is required to work on the Khan estate to repay her father’s debt, an impossible feat since the servants are charged for lodging and food. As she becomes part of the household, connects with the other servants, and learns more about the unlawful Khan family, she has to decide how much to risk to save the villages, her friends, and her future. She is counseled by her new teacher, “You always have a choice. Making choices even when they scare you because you know it’s the right thing to do —that’s bravery.” (210)

I am adding Amal Unbound to my list of novels featuring my 4 guest blogs on Strong Girls in MG.YA literature. She reminds me of such adolescents as Serafina (Serafina’s Promise by Ann E. Burg) and Valli (No Ordinary Day by Deborah Ellis).

As author Aisha Saeed wrote in her Author’s Note, “Amal is a fictional character, but she represents countless other girls in Pakistan and around the world who take a stand against inequality and fight for justice in often unrecognized but important ways.” In this way novels and characters can function as maps to

----------

Audacity by Melanie Crowder

Clara Lemlich, a 23-year-old Ukrainian immigrant, rose to a position of power in the women's labor movement, becoming the voice that incited the famous Uprising of the Twenty Thousand in 1909. (PBS)

Audacity has become one of my all-time favorites historical novels and some of the best writing I have read. I usually choose books about more contemporary issues, but I am finding the same issues appearing throughout history, wearing different masks. Unfortunately oppression, intolerance, and treatment of refugees are not past, and we still need people unafraid to stand for their own rights and those of others.

Audacity relates the true story of Clara Lemlich, a Russian Jewish immigrant with dreams of an education who sacrifices everything to fight for better working conditions for women in the factories of Manhattan's Lower East Side in the early 1900's.

Lyrically related in verse, the use of parallelism and the purposeful placement of the words is as effective as the words themselves. A great mentor text for poetry study.

The novel includes the history behind the story and a glossary of terms. What a wonderful "text" for a social studies class!

----------

Consider the Octopus by Nora Raleigh Baskin and Gay Polisner

"Consider the octopus, dude, duh,” I say out loud to myself because sometimes it helps to talk to someone. “That part is the important part. The octopus.” (88)

And the pink octopus avatar starts the chain of events which lead 12-year-old Sydney Miller (not marine biologist Dr. Sydney Miller of the Monterey Bay Aquarium) and her goldfish Rachel Carson to Oceana II, a ship researching the Great PGP.

When seventh-grader Jeremy JB Barnes, under the custody of his recently-divorced mother, chief scientist of the Oceana II, finds himself accompanying her on her mission “to sweep and vacuum up approximately eighty-eight thousand tons of garbage” called the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, he was less than enthusiastic. “I like the ocean plenty from the beach.”

Until the high school SEAmester students arrive, he is the only adolescent on board. But tasked with the job of inviting well-known scientists to the join them, JB inadvertently sends the invitation to the wrong Sydney Miller who jumps at the chance, looking for something to do this summer now that her best and only friend has moved away. Sydney and her grandmother agree, “It’s synchronicity” (91), the simultaneous occurrence of events which appear significantly related but have no discernible causal connection. “What psychologist Carl Jung called ‘meaningful coincidences’…” (228) However, “These signs we see all the time, the universe, these coincidences that we give meaning? They only work if we want them to…” (12)

And Sydney and Jeremy want these signs to work. Hiding Sydney on the ship, sometimes in plain sight with the help of two of the SEAmster girls, Sydney and JB hatch a plan to bring about the publicity the mission needs to retains its grant. “Maybe we’re here because we’re supposed to be here. Maybe the two of us are supposed to do something really important.” (144)

When you put two of my favorite authors together, what do readers get? A fun, important adventure with engaging characters who present two voices, representing two perspectives, and who show that, according to news reporter Damian Jacks, “Mark my words: kids and our youth. That’s who’s going to really help change things..… Kids, not adults, are the future of our planet.” (171)

And there is a lot of science and information about the polluting of the oceans. “It’s amazing how many people still don’t know how much waste—garbage,” she corrects herself, “is floating in the middle of the Pacific.” (226)

Readers learn about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and its importance to our environment. Besides the garbage that is killing sea life—birds and fish, this affects all of us.

Because every drop of water we have, all of it, circles around, evaporates into the sky, and comes back down as rain, or mist, or snow. It sinks into the ground and fills rivers, ponds, lakes, reservoirs, and the well in my backyard.

Water I shower with. Cook with.

And drink.

No new water is ever made.

This is all we’ve got. (167)

An important read, this novel could be included in an environmental impacts study in ELA or science classes, leading to more research on the topic.

----------

Fast Pitch by Nic Stone

Twelve-year-old Shanice Lockwood is captain of a softball team, the Firebirds, the only all-Black softball team in the Dixie Youth Softball Association. She comes from a long line of batball players—her father, her grandfather PopPop, her great-grandfather. Her one goal is for her team to win the state championship.

But her goal shifts when she meets her Great-Great Uncle Jack, her Great-Grampy JonJon’s brother.

Shanice’s father had to quit baseball when he blew out his knee, his father had to stop playing to support his family, but why did JonJon quit when he was successfully playing for the Negro American League and was one of the first Black players recruited to the MLB? When Shanice is taken to Peachtree Hills Place to meet her sometimes-senile uncle, he tells her that JonJon “didn’t do what they said he did…He was framed.” (46) “My brother ain’t no thief. He didn’t do it…But I know who did.” (47)

And Shanice is off on a quest to research the incident that caused her great grandfather to leave baseball and to see if she, with Jack’s information and JonJon’s leather journal, can clear his name while still trying to lead her softball team to victory.

Fast Pitch is a fun new novel by Nic Stone, full of batball, adventure, a little mystery, peer and family relationships, Negro League history, prejudice, and maybe a first crush.

----------

From the Desk of Zoe Washington by Janae Marks

Statistics affecting our children:

- The rate of wrongful convictions in the United States is estimated to be somewhere between 2 percent and 10 percent. When applied to an estimated prison population of 2.3 million, that means 46,000-230,000 innocent people are locked away. Once an innocent person is convicted, it is next to impossible to get the individual out of prison. Wrongful convictions happen for several reasons; one is bad lawyering by unprepared court-appointed defenders. (Chicago Tribune. March 14, 2018)

- African-American prisoners who are convicted of murder are about 50% more likely to be innocent than other convicted murderers. (National Registry of Exonerations, 2017)

- Currently, an estimated 2.7 million children—or 1 in 28 of those under the age of 18—have a biological mother or father who is incarcerated. According to the National Resource Center on Children and Families of the Incarcerated, approximately 10 million children have experienced parental incarceration at some point in their lives.

All the lying was wrong. But maybe it was okay to do something wrong if you were doing it for the right reason. (180)

Zoe Washington, a rising 7th grader who loves baking and aspires to be the first Black winner of the “Kids Bake Challenge” and publish her own cookbook, is in a fight with her former best friend Trevor, and is not looking forward to a summer without him and her other best friends Jasmine and Maya. But her life changes when, on her 12th birthday, she receives a letter from Marcus, her biological father, a man who she has never met because he has been in prison from before her birth—for murder.

For the longest time, I didn’t care whether or not I knew my birth father. I had my parents, and they were all I needed. But [Marcus’] letters were making me feel that a part of me was missing, like a chunk of my heart. I was finally filling in that hole. (121)

Zoe decides to write back, and as she and Marcus exchange letters and music recommendations, she begins to suspect that he doesn’t seem like a murderer. He admits that he did not kill the victim and that there was an alibi witness whom his lawyer never contacted.

Since her mother has forbidden communication with Marcus (and has been confiscating his letters for years), Zoe confides in her grandmother who explains, “People look at someone like Marcus—a tall, strong, dark-skinned boy—and they make assumptions about him. Even if it isn’t right. The jury, the judge, the public, even his own lawyer‑they all assumed Marcus must be guilty because he’s Black. It’s all part of systemic racism.” (133)

Zoe researches the Innocence Project, and she and Trevor, friends again, go on a search for Marcus’ alibi witness in a plan to first prove to herself that Marcus is innocent and if so, to exonerate him.

This is a truly valuable story to begin important conversations about social justice and disparities.

----------

Front Desk by Kelly Yang

Ten-year-old Mia moves to the head of my “Strong Girls in MG/YA Lit” as she becomes an activist and champion of those who cannot, or will not, stand up for themselves [“You don’t get it, kid. I’ve been fighting my whole life. I’m done. It’s no use fighting—people are gonna be the way they’re gonna be” (105)], teaches others the wrongs of prejudice and injustice, and forms a community from her neighbors, patrons, and fellow immigrants.

Mia and her parents emigrated from China to the United States for a more “free” life. In China her parents were professionals; in America they feel lucky to find a job managing a motel. But the owner, Mr. Yao, is unkind, unjust, cheap, and prejudiced. He reduces their salaries until they are working for lodging and a life of poverty. And while this is a novel about Mia who manages the front desk and helps her parents temporarily hide other Chinese immigrants who have been mistreated, it is really a novel of culture, prejudice, bullying, community, and, most of all, the power of writing. “It was the most incredible feeling ever, knowing that something I wrote actually changed someone’s life.” (218)

In America there are two roller coasters, and people are born to a life on one or the other, but Mia and her friend Lupe, whose family came from Mexico, have decided to break that cycle. Although bullied in school and warned by her mother that she will never be a “native” English writer, Mia develops her writing skills to help Hank gain employment after a wrongful arrest, free “Uncle” Zhang whose ID and passport were being held by his employer, share her story with her teacher and classmates, and finally persuade friends and strangers to take a chance on her family.

Mia is a representative of the “nearly twenty million immigrant children currently living in the United States, 30 percent of whom are living at or below poverty.” (Author’s Note). As such, this book will serve as a mirror for many readers, a map for others looking for ways to navigate young adolescent life, especially in a new culture, and as a window for those who will learn empathy for others they may see as different. Author Kelly Yang also shares the autobiographical elements of the novel in her Author’s Note.

Front Desk, with its very short chapters and challenging topics would be a meaningful and effective 10-minute read-aloud to begin Grade 4-7 daily reading workshop focus lessons. I would suggest projecting Mia’s letters since they show her revisions as she seeks to improve her language skills and word choices.

----------

Haven Jacobs Saves the Planet by Barbara Dee