- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

- Asian, Asian-American

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

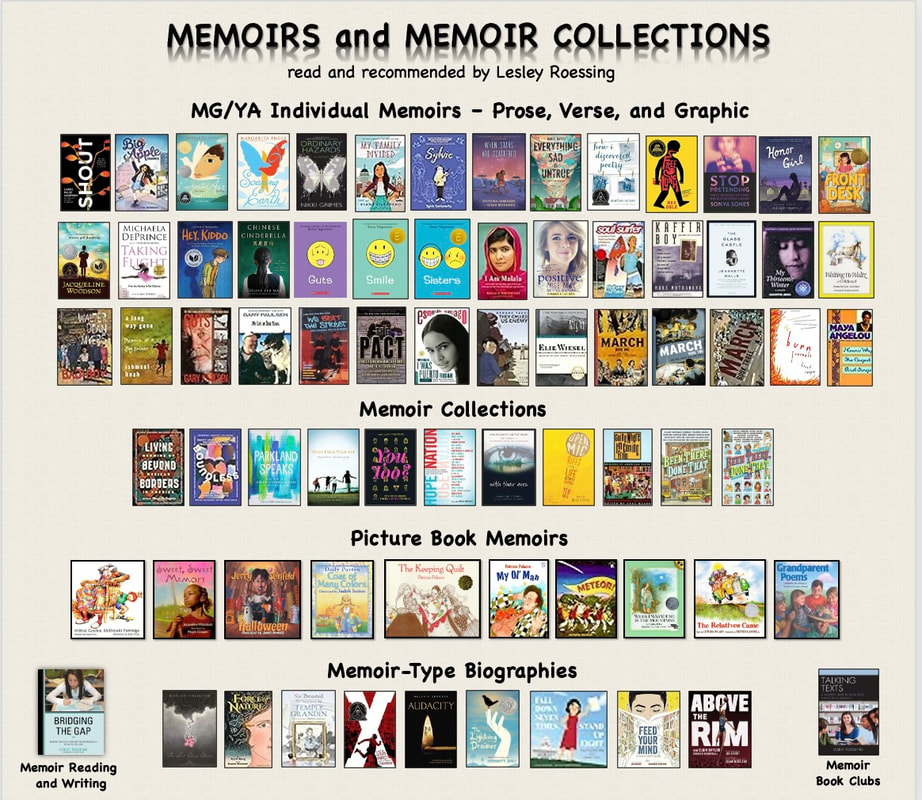

MEMOIR is writing that matters—for a variety of reasons. Because memoir is, in essence, narrative nonfiction, it contains elements of both narrative and informational writing/literature and provides an effective way to bridge the gap between these two types of writing and, as narrative nonfiction, memoir bridges the gap between fiction and informative texts and compels the application of diverse reading strategies, meeting multiple state standards.

What does memoir writing have to do with reading and Middle Grade/Young Adult literature? As I discuss in Bridging the Gap: Reading Critically & Writing Meaningfully to Get to the Core, reading memoirs provides mentor texts for writing memoirs. As readers read about people, places, objects, and events which are meaningful to published memoirists, they can notice and note how the memoirists write about these topics, using memoirs are mentors for their writings.

As literature, memoirs appeal to all readers because they are available at all reading levels and lengths; on all topics from dancing to sports to survival and resilience; in many formats, including prose, free verse, graphic, multi-formatted, and even as rhyming poems. Memoirs are written in first and third person, and can be humorous, poignant, and enlightening. Readers can together read whole-class memoirs, as described in Talking Texts: A Teachers' Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum, participate in Memoir Book Clubs or memoir essay clubs, and read self-selected memoirs individually. In addition to memoirs, there are novels, such as Front Desk, that closely follow the author’s life, and there are biographies written in the style of memoir in that they focus on a particular part of a person’s life or particular events based around a theme and emphasize personal experience, thoughts, feelings, reactions, and reflections rather than facts, at times written in first person..

Below are memoirs which I have read and memoirs read by my own middle grade students and in elementary and secondary classrooms where I have facilitated Memoir units which include memoir reading. My more-recently read memoirs are also reviewed below. Memoir reviews are divided into Individual Memoirs, Memoir Collections, and some Memoir-type Biographies. Picture book memoirs were read in elementary units I facilitated and employed as mentor texts for Reading Workshop focus reading lessons and for Writing Workshop memoir writing lessons in secondary grades.

What does memoir writing have to do with reading and Middle Grade/Young Adult literature? As I discuss in Bridging the Gap: Reading Critically & Writing Meaningfully to Get to the Core, reading memoirs provides mentor texts for writing memoirs. As readers read about people, places, objects, and events which are meaningful to published memoirists, they can notice and note how the memoirists write about these topics, using memoirs are mentors for their writings.

As literature, memoirs appeal to all readers because they are available at all reading levels and lengths; on all topics from dancing to sports to survival and resilience; in many formats, including prose, free verse, graphic, multi-formatted, and even as rhyming poems. Memoirs are written in first and third person, and can be humorous, poignant, and enlightening. Readers can together read whole-class memoirs, as described in Talking Texts: A Teachers' Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum, participate in Memoir Book Clubs or memoir essay clubs, and read self-selected memoirs individually. In addition to memoirs, there are novels, such as Front Desk, that closely follow the author’s life, and there are biographies written in the style of memoir in that they focus on a particular part of a person’s life or particular events based around a theme and emphasize personal experience, thoughts, feelings, reactions, and reflections rather than facts, at times written in first person..

Below are memoirs which I have read and memoirs read by my own middle grade students and in elementary and secondary classrooms where I have facilitated Memoir units which include memoir reading. My more-recently read memoirs are also reviewed below. Memoir reviews are divided into Individual Memoirs, Memoir Collections, and some Memoir-type Biographies. Picture book memoirs were read in elementary units I facilitated and employed as mentor texts for Reading Workshop focus reading lessons and for Writing Workshop memoir writing lessons in secondary grades.

Shout; Big Apple Diaries; Enchanted Air; Soaring Earth; Ordinary Hazards; My Family Divided; Sylvie; When Stars Are Scattered; Everything Sad Is Untrue; How I Discovered Poetry; Free Lunch; Honor Girl; Stop Pretending; Front Desk;

Brown Girl Dreaming; Taking Flight; ; Hey, Kiddo; Chinese Cinderella; Guts; Smile; Sisters; I Am Malala; Positive; Soul Surfer; Kaffir Boy; The Glass Caastle; My Thirteenth Winter; Waiting to Waltz; Bad Boy; A Long Way Gone; Guts; My Life in Dog Years; We Beat the Streets; The Pact; ; When I Was Puerto Rican; They Called Us Enemy; Night; March Book One; March Book Two; March Book Three; The Burn Journals; I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings;

Living Beyond Borders; Boundless; Parkland Speaks; When I Was Your Age—Volumes I & II; You Too?; Hope Nation; With Their Eyes; Open Mic; Going Where I’m Coming From; Been There, Done That—Writing Stories from Real Life; Been There, Done That—School Dazed;

Wilfrid Gordon McDonald Partridge; Sweet Sweet Memory; Halloween; Coat of Many Colors; The Keeping Quilt; My Ol’ Man; Meteor!; When I Was Young in the Mountains; The Relatives Came; Grandparent Poems;

The Last Cheery Blossom; Force of Nature; She Persisted—Temple Grandin; X; Audacity; The Lightning Dreamer; Fall Down Seven Times, Stand Up Eight; Feed Your Mind; Above the Rim

REVIEWS

INDIVIDUAL MEMOIRS:

INDIVIDUAL MEMOIRS:

Anderson, Laurie Halse. Shout. Penguin Young Readers Group, 2019.

When I think of Laurie Halse Anderson, writer, I think of well-told important stories—whether contemporary or historical, memorable characters, critical messages. When I think of Laurie Halse Anderson, person, I think of hugs, compassion, empathy, attention, and action. Now when I think of Laurie Halse Anderson, poet, I will ruminate on the power of words, the rhythm of words, the lyricism of words.

In this free verse memoir Anderson generously shares her life—the bottomless depths and the highest peaks—all that made her the force she is today. A challenging family life and the rape that “splits open your core with shrapnel,” clouds of doubt and self-loathing…anxiety, depression, and shame,” leaving “untreated pain / a cancer of the soul / that can kill you.” (69)

But also there were teachers, librarians, and the tutor who taught “the ants swarming across the pages” to form words and meaning, the lessons learned from Greek mythology, the gym teacher who cared enough to inspire her to shape-shift from “a lost stoner dirtbag / to a jock who hung out with exchange students, / wrote poetry for the literary magazine / and had a small group of …friends to sit with at lunch.” (88) and her home in Denmark which “taught me how to speak / again, how to reinterpret darkness and light, / strength and softness…redefine my true north / and start over.” (114)

She describes how the story of her first novel Speak found her and shares the origin of Melinda, “alone / with her fear / heart open, / unsheltered” (162)

Part Two bears witness to the stories of others, female and male, children, teens, and adults, connected through trauma and Melinda’s story, the questions of boys, confused, having never learned “the rules of intimacy or the law” (181) and the censorship, “the child of fear/ the father of ignorance” which keeps these stories away from them. Anderson raises the call to “sisters of the march” who never got the help they needed and deserved to “stand with us now / let’s be enraged aunties together.” (230)

And in Part Three the story returns to her American birth family, her father talking and “unrolling our family legacies of trauma and / silence.”

Shout is a tale of Truth: the truths that happened, the truths that we tell ourselves, the truths that we tell others, the truths that we live with; Shout is the power of Story—stories to tell and stories to be heard.

When I think of Laurie Halse Anderson, writer, I think of well-told important stories—whether contemporary or historical, memorable characters, critical messages. When I think of Laurie Halse Anderson, person, I think of hugs, compassion, empathy, attention, and action. Now when I think of Laurie Halse Anderson, poet, I will ruminate on the power of words, the rhythm of words, the lyricism of words.

In this free verse memoir Anderson generously shares her life—the bottomless depths and the highest peaks—all that made her the force she is today. A challenging family life and the rape that “splits open your core with shrapnel,” clouds of doubt and self-loathing…anxiety, depression, and shame,” leaving “untreated pain / a cancer of the soul / that can kill you.” (69)

But also there were teachers, librarians, and the tutor who taught “the ants swarming across the pages” to form words and meaning, the lessons learned from Greek mythology, the gym teacher who cared enough to inspire her to shape-shift from “a lost stoner dirtbag / to a jock who hung out with exchange students, / wrote poetry for the literary magazine / and had a small group of …friends to sit with at lunch.” (88) and her home in Denmark which “taught me how to speak / again, how to reinterpret darkness and light, / strength and softness…redefine my true north / and start over.” (114)

She describes how the story of her first novel Speak found her and shares the origin of Melinda, “alone / with her fear / heart open, / unsheltered” (162)

Part Two bears witness to the stories of others, female and male, children, teens, and adults, connected through trauma and Melinda’s story, the questions of boys, confused, having never learned “the rules of intimacy or the law” (181) and the censorship, “the child of fear/ the father of ignorance” which keeps these stories away from them. Anderson raises the call to “sisters of the march” who never got the help they needed and deserved to “stand with us now / let’s be enraged aunties together.” (230)

And in Part Three the story returns to her American birth family, her father talking and “unrolling our family legacies of trauma and / silence.”

Shout is a tale of Truth: the truths that happened, the truths that we tell ourselves, the truths that we tell others, the truths that we live with; Shout is the power of Story—stories to tell and stories to be heard.

Bermudez, Alyssa. Big Apple Diaries

Big Apple Diaries is based on the author’s actual journals which she has illustrated as a graphic diary memoir encompassing the time from September 2000 to June 2002.

Alyssa Bermudez was the child of divorced parents, dividing her time between her Puerto Rican father who lived in Manhattan and her Italian-British mother who lived in Queens. This diary begins in 7th grade where “It seems that suddenly every grade you get and everything you do matters…. Now our friends are obsessed with who has a crush on who. And who is the coolest. There is all of this pressure to be popular and smart or face a dim future being a weirdo with no job.” (10)

Alyssa is not particularly popular, but not particularly unpopular either, has a much older half-brother and two best friends, Lucy and Carmen, and is an artist who wants to become a shoe designer. In this 7th grade year, she experiences her first crush—Alejandro from Columbia. Her diary takes us through the typical middle school year familiar to most of our adolescent readers. “Yesterday I did something very stupid. I knew it was stupid at the time and I still did it anyway. It’s like the drive to be popular makes me see things through stupid lenses.” (83) Typical preteen, she does many “stupid things”: shave her eyebrows, accidently dye her hair orange, cut school.

Two months before her thirteenth birthday, the attacks of September 11th occur. Alyssa’s mother worked in a building that faced the Twin Towers. She escaped and caught the last train to Queens. Her father did work in the World Trade Center but was meeting a client in Jersey City that morning (and bought skates to skate the 19.5 miles back to his Manhattan home). Overcome with emotion, Alyssa writes no entries for that day and the following few.

After that time Alyssa recognizes, “I sort of feel like I have no control over anything. I want to come back to the normal life I knew and the Twin Towers that I visited with Dad all the time.”(195) She finds herself changing, maturing: “When things can change in an instant, it’s hard to accept it. I want to make the right decisions and prove my worth. I want to be brave.” (211)

On her thirteenth birthday she begins to wonder “Who am I?” and begins thinking about her character and how she may want to change. Her diary takes the reader through graduation to a future where “Some things I’ll take with me and other things I will leave behind.” (274)

Big Apple Diaries, a graphic memoir of an NYC adolescent who experienced 9/11 as part of her middle grade years adds yet another perspective or dimension to the other novels in this 9/11 book collection.

Big Apple Diaries is based on the author’s actual journals which she has illustrated as a graphic diary memoir encompassing the time from September 2000 to June 2002.

Alyssa Bermudez was the child of divorced parents, dividing her time between her Puerto Rican father who lived in Manhattan and her Italian-British mother who lived in Queens. This diary begins in 7th grade where “It seems that suddenly every grade you get and everything you do matters…. Now our friends are obsessed with who has a crush on who. And who is the coolest. There is all of this pressure to be popular and smart or face a dim future being a weirdo with no job.” (10)

Alyssa is not particularly popular, but not particularly unpopular either, has a much older half-brother and two best friends, Lucy and Carmen, and is an artist who wants to become a shoe designer. In this 7th grade year, she experiences her first crush—Alejandro from Columbia. Her diary takes us through the typical middle school year familiar to most of our adolescent readers. “Yesterday I did something very stupid. I knew it was stupid at the time and I still did it anyway. It’s like the drive to be popular makes me see things through stupid lenses.” (83) Typical preteen, she does many “stupid things”: shave her eyebrows, accidently dye her hair orange, cut school.

Two months before her thirteenth birthday, the attacks of September 11th occur. Alyssa’s mother worked in a building that faced the Twin Towers. She escaped and caught the last train to Queens. Her father did work in the World Trade Center but was meeting a client in Jersey City that morning (and bought skates to skate the 19.5 miles back to his Manhattan home). Overcome with emotion, Alyssa writes no entries for that day and the following few.

After that time Alyssa recognizes, “I sort of feel like I have no control over anything. I want to come back to the normal life I knew and the Twin Towers that I visited with Dad all the time.”(195) She finds herself changing, maturing: “When things can change in an instant, it’s hard to accept it. I want to make the right decisions and prove my worth. I want to be brave.” (211)

On her thirteenth birthday she begins to wonder “Who am I?” and begins thinking about her character and how she may want to change. Her diary takes the reader through graduation to a future where “Some things I’ll take with me and other things I will leave behind.” (274)

Big Apple Diaries, a graphic memoir of an NYC adolescent who experienced 9/11 as part of her middle grade years adds yet another perspective or dimension to the other novels in this 9/11 book collection.

Engle, Margarita. Enchanted Air: Two Cultures, Two Wings: A Memoir.

Through this memoir in verse, the narrative of Engle’s childhood as a Cuban-American growing up in LA during the 1950-60’s, readers can experience the challenge of children torn between cultures and, and learn about the Cold War. When the revolution broke out in Cuba, Engle’s family fears for their far-away family in Cuba, a family they can no longer visit. Then, the Bay of Pigs Invasion creates hostile US/Cuba relations.

I learned more about Cuban history, the Cuban Missile Crisis. and Cuban-American relations from this memoir than from my history courses as I lived through the times with young Margarita.

Through this memoir in verse, the narrative of Engle’s childhood as a Cuban-American growing up in LA during the 1950-60’s, readers can experience the challenge of children torn between cultures and, and learn about the Cold War. When the revolution broke out in Cuba, Engle’s family fears for their far-away family in Cuba, a family they can no longer visit. Then, the Bay of Pigs Invasion creates hostile US/Cuba relations.

I learned more about Cuban history, the Cuban Missile Crisis. and Cuban-American relations from this memoir than from my history courses as I lived through the times with young Margarita.

Engle, Margarita. Soaring Earth. Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 2019.

I eagerly read Engle’s second memoir, a continuation of Enchanted Air which covers the years 1966-1973. For me, this was more reminiscing, than learning, about the lifestyle and events. As a reader of about the same age of young adult Margarita and possibly geographically crossing paths at some point, I am quite familiar with that time period.

Engle depicts a feeling of duality as she longs for Cuba, home of her “invisible twin,” now that travel is forbidden for North Americans.

Readers witness firsthand the era of hippies, an unpopular war, draft notices, drugs, and Martin Luther King’s speeches and assassination, riots, Cambodia, picket lines, as they follow 17-year-old bell-bottomed Margarita from her senior year of high school to her first university experience, fascinating college courses, books, unfortunate choices of boyfriends, dropping out, travel, homelessness, homecoming, college, agricultural studies, and finally, love.

At one point young Margarita as a member of a harsh creative writing critique group says, “If I ever scribble again, I’ll keep every treasured word secret.” (31). Thank goodness she didn’t. This beautifully written verse novel shares her story—and a bit of history—through poetry in many formats, including tanka, haiku, concrete, and the power of words.

I eagerly read Engle’s second memoir, a continuation of Enchanted Air which covers the years 1966-1973. For me, this was more reminiscing, than learning, about the lifestyle and events. As a reader of about the same age of young adult Margarita and possibly geographically crossing paths at some point, I am quite familiar with that time period.

Engle depicts a feeling of duality as she longs for Cuba, home of her “invisible twin,” now that travel is forbidden for North Americans.

Readers witness firsthand the era of hippies, an unpopular war, draft notices, drugs, and Martin Luther King’s speeches and assassination, riots, Cambodia, picket lines, as they follow 17-year-old bell-bottomed Margarita from her senior year of high school to her first university experience, fascinating college courses, books, unfortunate choices of boyfriends, dropping out, travel, homelessness, homecoming, college, agricultural studies, and finally, love.

At one point young Margarita as a member of a harsh creative writing critique group says, “If I ever scribble again, I’ll keep every treasured word secret.” (31). Thank goodness she didn’t. This beautifully written verse novel shares her story—and a bit of history—through poetry in many formats, including tanka, haiku, concrete, and the power of words.

Sylvie Kantorovitz. Sylvie.

Christine: “I hate being different!”

Sylvie [thinking]: “Her too?”

Christine: “But really, we are ALL different! In one way or another. And some differences come from US! Like how you love to draw!” (177)

In Sylvie Kantorovitz’s graphic memoir, readers literally watch Sylvie grow up through the author’s own illustrations. The memoir begins in France where Sylvie, her brother, and her parents live in the school where her father is principal and continues through the birth of two more siblings and later a move during high school to Lyon.

Sylvie has many worries in common with many of her readers. She doesn’t want to be different. She was born in Morocco, so some of her classmates say she is not “French.” “Oh, how I wish I was born in France like all the others!” (73) She and her younger brother Alibert are the only Jewish children in their school. “Whenever possible I let people assume I was like them.” ((74)

Sylvie also has a complicated family life. Her parents are always fighting. While she father is kind and supportive, her mother is very hard on her. “[An A] doesn’t count if the others also got As.” (6) Her mother’s values are very different from Sylvie’s. “Being ‘feminine’ was important to Mom. It didn’t feel that important to me.” (110-111) Her mother always seems to be angry, and when Alibert does not do well in school, he is sent away to a boarding school. Sylvie just doesn’t understand her mother. “Could Alibert be right? Could someone actually LIKE being angry?” (135) “Was I allowed to feel so conflicted about my own mother? Could I feel shame and anger and still love her?” (131)

In school when the teacher asks the students if anyone knows what they want to be when they grow up, to Sylvie’s surprise, everyone else does. “I was the only one without a plan for the future. Was something wrong with me?” (38)

In her last year of high school Sylvie has a boyfriend, Pierre, and hearing about his family’s troubles—his mother is depressed and sometimes stays in bed all day, “I wondered if every family had an ongoing drama, hidden from the outside world.” (239) Maybe her family is not so different.

Through it all from a young age, Sylvie realizes that “drawing was what I really loved to do.” (10) but because of her mother’s disdain, she didn’t see it as a profession. Finally, with her father’s support and the courage to confront her mother, Sylvie has come up with a long-term plan for independence.

A memoir is an account of one's personal life and experiences built on the memory of the writer and formed by the present reflection on the past. This memoir is enhanced by its visual quality.

But what I would find most important to adolescent readers is the realization that while we all are different, at the same time we are all very much alike.

Christine: “I hate being different!”

Sylvie [thinking]: “Her too?”

Christine: “But really, we are ALL different! In one way or another. And some differences come from US! Like how you love to draw!” (177)

In Sylvie Kantorovitz’s graphic memoir, readers literally watch Sylvie grow up through the author’s own illustrations. The memoir begins in France where Sylvie, her brother, and her parents live in the school where her father is principal and continues through the birth of two more siblings and later a move during high school to Lyon.

Sylvie has many worries in common with many of her readers. She doesn’t want to be different. She was born in Morocco, so some of her classmates say she is not “French.” “Oh, how I wish I was born in France like all the others!” (73) She and her younger brother Alibert are the only Jewish children in their school. “Whenever possible I let people assume I was like them.” ((74)

Sylvie also has a complicated family life. Her parents are always fighting. While she father is kind and supportive, her mother is very hard on her. “[An A] doesn’t count if the others also got As.” (6) Her mother’s values are very different from Sylvie’s. “Being ‘feminine’ was important to Mom. It didn’t feel that important to me.” (110-111) Her mother always seems to be angry, and when Alibert does not do well in school, he is sent away to a boarding school. Sylvie just doesn’t understand her mother. “Could Alibert be right? Could someone actually LIKE being angry?” (135) “Was I allowed to feel so conflicted about my own mother? Could I feel shame and anger and still love her?” (131)

In school when the teacher asks the students if anyone knows what they want to be when they grow up, to Sylvie’s surprise, everyone else does. “I was the only one without a plan for the future. Was something wrong with me?” (38)

In her last year of high school Sylvie has a boyfriend, Pierre, and hearing about his family’s troubles—his mother is depressed and sometimes stays in bed all day, “I wondered if every family had an ongoing drama, hidden from the outside world.” (239) Maybe her family is not so different.

Through it all from a young age, Sylvie realizes that “drawing was what I really loved to do.” (10) but because of her mother’s disdain, she didn’t see it as a profession. Finally, with her father’s support and the courage to confront her mother, Sylvie has come up with a long-term plan for independence.

A memoir is an account of one's personal life and experiences built on the memory of the writer and formed by the present reflection on the past. This memoir is enhanced by its visual quality.

But what I would find most important to adolescent readers is the realization that while we all are different, at the same time we are all very much alike.

Nayeri, Daniel. Everything Sad Is Untrue.

Years ago I heard Tim O’Brien, author of The Things They Carried, tell an audience, “You don’t have to tell a true story to tell the truth.” When I facilitate memoir workshops, I advise writers that memoir is how the memoirist remembers and interprets events.

EVERYTHING SAD IS UNTRUE is the story of Khosrou Nayeri on his way to becoming Daniel Nayeri. It is the stories of his childhood in Iran, in Dubai, in a refugee “camp” in Italy, in his relocation home in Oklahoma; it is also the stories of the Persian and Iranian people and history. It is a recounting that flits from time to time and person to person and place to place, inviting readers to participate as we form a relationship with the storyteller.

This is a collection of stories reminiscent of 1001 Arabian Nights. In fact, Daniel frequently compares himself to Scheherazade, telling readers, “Every story is the sound of a storyteller begging to stay alive.” (59) The author further explains that, in his case, “You don’t get to choose what you remember. A patchwork memory is the shame of a refugee.” (49) and later explains, “Memories are just stories we tell ourselves, after all. (349)

Everything Sad is Untrue reminds me of my favorite children’s book Haroun and the Sea of Stories in which Salman Rushdie proves “the use of stories that aren’t even true,” a novel that likewise blends Eastern and Western cultures.

But the most important feature of this wonderful novel is the author’s voice which comes through on every page. As our storyteller discloses, “The point of Nights is that if you spend time with each other—if we really listen in the parlors of our minds and look at each other as we were meant to be seen—then we would fall in love.…The stories aren’t the thing. The thing is the story of the story. The spending of the time. The falling in love.” (301) And that is why I am not recounting a summary of this story as in many of my reviews. I fell in love with the telling of the story.

A book certainly deserving its 2021 Michael L. Printz award, an award which annually honors the best book written for teens, based entirely on its literary merit.

.

Years ago I heard Tim O’Brien, author of The Things They Carried, tell an audience, “You don’t have to tell a true story to tell the truth.” When I facilitate memoir workshops, I advise writers that memoir is how the memoirist remembers and interprets events.

EVERYTHING SAD IS UNTRUE is the story of Khosrou Nayeri on his way to becoming Daniel Nayeri. It is the stories of his childhood in Iran, in Dubai, in a refugee “camp” in Italy, in his relocation home in Oklahoma; it is also the stories of the Persian and Iranian people and history. It is a recounting that flits from time to time and person to person and place to place, inviting readers to participate as we form a relationship with the storyteller.

This is a collection of stories reminiscent of 1001 Arabian Nights. In fact, Daniel frequently compares himself to Scheherazade, telling readers, “Every story is the sound of a storyteller begging to stay alive.” (59) The author further explains that, in his case, “You don’t get to choose what you remember. A patchwork memory is the shame of a refugee.” (49) and later explains, “Memories are just stories we tell ourselves, after all. (349)

Everything Sad is Untrue reminds me of my favorite children’s book Haroun and the Sea of Stories in which Salman Rushdie proves “the use of stories that aren’t even true,” a novel that likewise blends Eastern and Western cultures.

But the most important feature of this wonderful novel is the author’s voice which comes through on every page. As our storyteller discloses, “The point of Nights is that if you spend time with each other—if we really listen in the parlors of our minds and look at each other as we were meant to be seen—then we would fall in love.…The stories aren’t the thing. The thing is the story of the story. The spending of the time. The falling in love.” (301) And that is why I am not recounting a summary of this story as in many of my reviews. I fell in love with the telling of the story.

A book certainly deserving its 2021 Michael L. Printz award, an award which annually honors the best book written for teens, based entirely on its literary merit.

.

Nelson, Marilyn. How I Discovered Poetry. Dial Books, 2014.

Growing up through the Fifties, Marilyn Nelson tells her story through fifty sonnet-style free-verse poems. Each poem has a location and year as readers follow Marilyn through her childhood on her quest to become the poet she is today.

Ms. Nelson’s father was one of the first African American career officers in the United States Air Force, and as a military child, Marilyn moved frequently, literally crossing the country, from Ohio to Texas to Kansas to California to Oklahoma to Maine, experiencing the country, sometimes the only black student in an “all-except-for-me white class.” Readers can identify with the universal childhood experiences she shares, but there are also incidents driven by race and the time period providing history that we can learn from this memoir.

This is a memoir of beginnings and endings and the search for identity and changing expectations—our own and that of others—in a confusing, sometimes hostile, world. It is about language and cloud-gathering and discovering poetry and the power of words.

Growing up through the Fifties, Marilyn Nelson tells her story through fifty sonnet-style free-verse poems. Each poem has a location and year as readers follow Marilyn through her childhood on her quest to become the poet she is today.

Ms. Nelson’s father was one of the first African American career officers in the United States Air Force, and as a military child, Marilyn moved frequently, literally crossing the country, from Ohio to Texas to Kansas to California to Oklahoma to Maine, experiencing the country, sometimes the only black student in an “all-except-for-me white class.” Readers can identify with the universal childhood experiences she shares, but there are also incidents driven by race and the time period providing history that we can learn from this memoir.

This is a memoir of beginnings and endings and the search for identity and changing expectations—our own and that of others—in a confusing, sometimes hostile, world. It is about language and cloud-gathering and discovering poetry and the power of words.

Ogle, Rex. Free Lunch.

On the first day of middle school Rex Ogle arrives at school with a black eye and his name in the Free Lunch Program registry.

As Rex lives through a year of avoiding being hit by his mentally-unstable mother and her abusive boyfriend; taking care of his little brother; sleeping in a room with only a sleeping bag; having his one possession—his Sony boombox, a present from his real dad—pawned; surviving a teacher who treats him as “less than;” and moving to government-subsidized housing in full view of the school, he still feels the responsibility to help his mother. When his friend Liam steals some candy at the grocery “because [he] can,” the cashier asks to see Rex’s pockets, and Rex learns the double standard for the wealthy and the poor.

When his friends all join the football team, Rex has no one to sit with at lunch. But finally, Rex makes a new friend at school, Ethan, a boy who may have seems a “total weirdo” at first but turns out to be a good person and true friend and have his own family problems, and Rex’s teacher learns to admit and face her own prejudices. Rex comes to the realization that “Mom didn’t sign me up for the Free Lunch Program to punish me. She did it so I could have food….Things are not as black and white as I thought. Maybe some things are gray, somewhere in between.” (188) As Ethan tells him, “…no one has a perfect life. There is no such thing as ‘perfect.’ It’s just an idea.” (195).

However, some lives are indeed less perfect. About 15 million children in the United States – 21% of all children – live in families with incomes below the federal poverty threshold. Forty-three percent of children live in households which earn less than necessary to cover basic expenses (NCCP). And Rex Ogle, author, was one of them; Free Lunch is his personal story.

Free Lunch, and other novels and memoirs about children affected by poverty, are necessary additions to classroom and school libraries so that readers can see their lives and the lives of their peers reflected and valued through story.

On the first day of middle school Rex Ogle arrives at school with a black eye and his name in the Free Lunch Program registry.

As Rex lives through a year of avoiding being hit by his mentally-unstable mother and her abusive boyfriend; taking care of his little brother; sleeping in a room with only a sleeping bag; having his one possession—his Sony boombox, a present from his real dad—pawned; surviving a teacher who treats him as “less than;” and moving to government-subsidized housing in full view of the school, he still feels the responsibility to help his mother. When his friend Liam steals some candy at the grocery “because [he] can,” the cashier asks to see Rex’s pockets, and Rex learns the double standard for the wealthy and the poor.

When his friends all join the football team, Rex has no one to sit with at lunch. But finally, Rex makes a new friend at school, Ethan, a boy who may have seems a “total weirdo” at first but turns out to be a good person and true friend and have his own family problems, and Rex’s teacher learns to admit and face her own prejudices. Rex comes to the realization that “Mom didn’t sign me up for the Free Lunch Program to punish me. She did it so I could have food….Things are not as black and white as I thought. Maybe some things are gray, somewhere in between.” (188) As Ethan tells him, “…no one has a perfect life. There is no such thing as ‘perfect.’ It’s just an idea.” (195).

However, some lives are indeed less perfect. About 15 million children in the United States – 21% of all children – live in families with incomes below the federal poverty threshold. Forty-three percent of children live in households which earn less than necessary to cover basic expenses (NCCP). And Rex Ogle, author, was one of them; Free Lunch is his personal story.

Free Lunch, and other novels and memoirs about children affected by poverty, are necessary additions to classroom and school libraries so that readers can see their lives and the lives of their peers reflected and valued through story.

Sones, Sonya. Stop Pretending: What Happened When My Big Sister Went Crazy. HarperTeen, 1999.

I first met Sonya Sones when she talked about how she came to write about the topic of this memoir, her sister’s mental illness, in verse and heard her read some of the poems,

Through free verse, the author captures the highs and lows of her thirteenth year, from “My Sister’s Christmas Eve Breakdown” to her fantasy of coming “To the Rescue” to the heartbreak of her “February 15th” birthday spent in the hospital visiting her sister to the joy of spending “Memorial Day” alone with Father to finally playing scrabble “In the Visiting Room” after her sister’ situation and her family’s adaption to it had become somewhat “BETTER.”

When I read selected poems aloud to my students, I wished they could see the line breaks—I frequently refer to Sones as the Master of Line Breaks—and reading aloud, I would pause a microsecond shorter than a comma, so my students could feel the poetry.

I first met Sonya Sones when she talked about how she came to write about the topic of this memoir, her sister’s mental illness, in verse and heard her read some of the poems,

Through free verse, the author captures the highs and lows of her thirteenth year, from “My Sister’s Christmas Eve Breakdown” to her fantasy of coming “To the Rescue” to the heartbreak of her “February 15th” birthday spent in the hospital visiting her sister to the joy of spending “Memorial Day” alone with Father to finally playing scrabble “In the Visiting Room” after her sister’ situation and her family’s adaption to it had become somewhat “BETTER.”

When I read selected poems aloud to my students, I wished they could see the line breaks—I frequently refer to Sones as the Master of Line Breaks—and reading aloud, I would pause a microsecond shorter than a comma, so my students could feel the poetry.

Thrash, Maggie. Honor Girl: A Graphic Memoir. Candlewick Press, 2015.

Honor Girl is, as the title states, a graphic memoir, a format which is gaining popularity. Honor Girl is about a summer of discovery and identity.

Maggie spent every summer at Camp Bellflower for girls. A typical Southern adolescent, she is a fan of the Backstreet Boys and awaiting her first kiss. However, this summer, the summer she is fifteen, she unexpectedly falls in love with a female counselor, surprising herself and questioning her sexuality as she experiences new, complex emotions. This is an honest coming out story, and the simple art style of this memoir supports and adds to the story.

Honor Girl is, as the title states, a graphic memoir, a format which is gaining popularity. Honor Girl is about a summer of discovery and identity.

Maggie spent every summer at Camp Bellflower for girls. A typical Southern adolescent, she is a fan of the Backstreet Boys and awaiting her first kiss. However, this summer, the summer she is fifteen, she unexpectedly falls in love with a female counselor, surprising herself and questioning her sexuality as she experiences new, complex emotions. This is an honest coming out story, and the simple art style of this memoir supports and adds to the story.

Yang, Kelly. Front Desk.

Front Desk’s ten-year-old Mia moves to the head of my “Strong Girls in MG/YA Literature” list as she becomes an activist and champion of those who cannot, or will not, stand up for themselves [“You don’t get it, kid. I’ve been fighting my whole life. I’m done. It’s no use fighting—people are gonna be the way they’re gonna be” (105)], teaches others the wrongs of prejudice and injustice, and forms a community from her neighbors, patrons, and fellow immigrants.

Mia and her parents emigrated from China to the United States for a more “free” life. In China her parents were professionals; in America they feel lucky to find a job managing a motel. But the owner, Mr. Yao, is unkind, unjust, cheap, and prejudiced. He reduces their salaries until they are working for lodging and a life of poverty. And while this is a novel about Mia who manages the front desk and helps her parents temporarily hide other Chinese immigrants who have been mistreated, it is really a novel of culture, prejudice, bullying, community, and, most of all, the power of writing. “It was the most incredible feeling ever, knowing that something I wrote actually changed someone’s life.” (218)

In America there are two roller coasters, and people are born to a life on one or the other, but Mia and her friend Lupe, whose family came from Mexico, have decided to break that cycle. Although bullied in school and warned by her mother that she will never be a “native” English writer, Mia develops her writing skills to help Hank gain employment after a wrongful arrest, free “Uncle” Zhang whose ID and passport were being held by his employer, share her story with her teacher and classmates, and finally persuade friends and strangers to take a chance on her family.

Mia is a representative of the “nearly twenty million immigrant children currently living in the United States, 30 percent of whom are living at or below poverty.” (Author’s Note). As such, this book will serve as a mirror for many readers, a map for others looking for ways to navigate young adolescent life, especially in a new culture, and as a window for those who will learn empathy for others they may see as different. Author Kelly Yang also shares the autobiographical elements of the novel in her Author’s Note.

Front Desk, with its very short chapters and challenging topics would be a meaningful and effective 10-minute read-aloud to begin Grade 4-7 daily reading workshop focus lessons. I would suggest projecting Mia’s letters since they show her revisions as she seeks to improve her language skills and word choices.

---------------

Front Desk’s ten-year-old Mia moves to the head of my “Strong Girls in MG/YA Literature” list as she becomes an activist and champion of those who cannot, or will not, stand up for themselves [“You don’t get it, kid. I’ve been fighting my whole life. I’m done. It’s no use fighting—people are gonna be the way they’re gonna be” (105)], teaches others the wrongs of prejudice and injustice, and forms a community from her neighbors, patrons, and fellow immigrants.

Mia and her parents emigrated from China to the United States for a more “free” life. In China her parents were professionals; in America they feel lucky to find a job managing a motel. But the owner, Mr. Yao, is unkind, unjust, cheap, and prejudiced. He reduces their salaries until they are working for lodging and a life of poverty. And while this is a novel about Mia who manages the front desk and helps her parents temporarily hide other Chinese immigrants who have been mistreated, it is really a novel of culture, prejudice, bullying, community, and, most of all, the power of writing. “It was the most incredible feeling ever, knowing that something I wrote actually changed someone’s life.” (218)

In America there are two roller coasters, and people are born to a life on one or the other, but Mia and her friend Lupe, whose family came from Mexico, have decided to break that cycle. Although bullied in school and warned by her mother that she will never be a “native” English writer, Mia develops her writing skills to help Hank gain employment after a wrongful arrest, free “Uncle” Zhang whose ID and passport were being held by his employer, share her story with her teacher and classmates, and finally persuade friends and strangers to take a chance on her family.

Mia is a representative of the “nearly twenty million immigrant children currently living in the United States, 30 percent of whom are living at or below poverty.” (Author’s Note). As such, this book will serve as a mirror for many readers, a map for others looking for ways to navigate young adolescent life, especially in a new culture, and as a window for those who will learn empathy for others they may see as different. Author Kelly Yang also shares the autobiographical elements of the novel in her Author’s Note.

Front Desk, with its very short chapters and challenging topics would be a meaningful and effective 10-minute read-aloud to begin Grade 4-7 daily reading workshop focus lessons. I would suggest projecting Mia’s letters since they show her revisions as she seeks to improve her language skills and word choices.

---------------

MEMOIR COLLECTIONS:

Brock, Rose, ed. Hope Nation: YA Authors Share Personal Moments of Inspiration.

Contemporary adolescents are dealing with a variety of issues and feelings of powerlessness in a complex world that sometimes feels hopeless.

Twenty-four YA authors speak to teens through poetry, essays, and letters of hope in this nonfiction collection. They inspire readers by sharing difficult childhoods and obstacles and experiences they overcame. Readers will appreciate the personal stories of authors of their favorite novels, such as David Levithan, Julie Murphy, Angie Thomas, Nic Stone, Libba Bray, Nicola Yoon, Jason Reynolds, and I.W.Gregorio.

Contemporary adolescents are dealing with a variety of issues and feelings of powerlessness in a complex world that sometimes feels hopeless.

Twenty-four YA authors speak to teens through poetry, essays, and letters of hope in this nonfiction collection. They inspire readers by sharing difficult childhoods and obstacles and experiences they overcame. Readers will appreciate the personal stories of authors of their favorite novels, such as David Levithan, Julie Murphy, Angie Thomas, Nic Stone, Libba Bray, Nicola Yoon, Jason Reynolds, and I.W.Gregorio.

Ehrlich, Amy, ed. When I Was Your Age, Volumes I & II: Original Stories about Growing Up.

A collection of short funny, poignant, exciting memoirs by twenty well-known MG/YA authors, including Avi, Francesca Lia Block, Joseph Bruchac, Susan Cooper, Paul Fleischman, Karen Hesse, James Howe, E. L. Konigsburg, Reeve LIndbergh, Norma Fox Mazer, Nicholasa Mohr, Kyoko Mori, Walter Dean Myers, Howard Norman, Mary Pope Osborne, Katherine Paterson, Michael J. Rosen, Rita Williams-Garcia, Laurence Yep, and Jane Yolen.

The authors also explain why they chose a particular memory as the basis for their memoir. Stories focus on events, people, places, or objects, and, in that way, lend themselves to serving as mentor texts for different types of memoir writing.

A collection of short funny, poignant, exciting memoirs by twenty well-known MG/YA authors, including Avi, Francesca Lia Block, Joseph Bruchac, Susan Cooper, Paul Fleischman, Karen Hesse, James Howe, E. L. Konigsburg, Reeve LIndbergh, Norma Fox Mazer, Nicholasa Mohr, Kyoko Mori, Walter Dean Myers, Howard Norman, Mary Pope Osborne, Katherine Paterson, Michael J. Rosen, Rita Williams-Garcia, Laurence Yep, and Jane Yolen.

The authors also explain why they chose a particular memory as the basis for their memoir. Stories focus on events, people, places, or objects, and, in that way, lend themselves to serving as mentor texts for different types of memoir writing.

Gurtler, Janet, ed. You Too?: 25 Voices Share Their #MeToo Stories.

Teens should realize that no young person—female or male—should be subject to sexual assault, or made to feel unsafe, less than, or degraded.

Twenty-five YA authors share personal stories of physical and verbal abuse, harassment, and assault—from strangers, acquaintances, and family members. Included in this volume are stories of trial, loss, shame, and resilience and, most important, acknowledging self-worth. These essays illustrate to adolescent readers that there is no “right” way to deal with trauma; each survivor has to find their own way of processing and surviving trauma. This book will not only provide a mirror, sometimes unexpectedly, for some readers and a window for others, helping to build empathy, but will offer a map for many readers. This is a book that needs to be read and discussed by young women and men and the adults in their lives.

Some familiar authors of diverse cultures who share their experiences are Eileen Hopkins, Cheryl Rainfield, Patty Blout, Ronni Davis, Nicholas DiDomizio, Andrea L. Rogers, and Lulabel Seitz.

Teens should realize that no young person—female or male—should be subject to sexual assault, or made to feel unsafe, less than, or degraded.

Twenty-five YA authors share personal stories of physical and verbal abuse, harassment, and assault—from strangers, acquaintances, and family members. Included in this volume are stories of trial, loss, shame, and resilience and, most important, acknowledging self-worth. These essays illustrate to adolescent readers that there is no “right” way to deal with trauma; each survivor has to find their own way of processing and surviving trauma. This book will not only provide a mirror, sometimes unexpectedly, for some readers and a window for others, helping to build empathy, but will offer a map for many readers. This is a book that needs to be read and discussed by young women and men and the adults in their lives.

Some familiar authors of diverse cultures who share their experiences are Eileen Hopkins, Cheryl Rainfield, Patty Blout, Ronni Davis, Nicholas DiDomizio, Andrea L. Rogers, and Lulabel Seitz.

Lerner, Sarah. Parkland Speaks: Survivors from Marjory Stoneman Douglas Share Their Stories.

On the first anniversary of the shootings at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, I read the writings of the survivors of that unspeakable event. In this “yearbook,” students and teachers share their stories of grief, terror, anger, and hope, and honor those who died through narratives, letters, speeches, free verse and rhyming poetry, and art. As the editor, MSD English and journalism teacher Sarah Lerner, writes, “Watching my students find their voices after someone tried to silence them was impressive…. It was awe-inspiring. It was brave…. They turned their grief into words, into pictures, into something that helped them begin the healing process.”

“[The news] keeps coming in,

It doesn’t pause

Or give you a break. It keeps hitting you

With debilitating blows, one after the other,

As those missing responses remain empty,

And your messages remain unread.” –C. Chalita

“We entered a war zone.…I came out of that building a different person than the one who left for school that day.” –J. DeArce

“Somehow, through the darkness, we found another shade of love, too

something that outweighed the hate and swept the grays away.

A love so strong it transcended colors, something so empowering and true it couldn’t be traced to one hue.” – H. Korr

“I just don’t want to let go of all the people I love,

I want to continuously tell them “I love you” until

My voice is raw and my throat is sore” – S. Bonnin

“I invite you [Dear Mr. President] to learn, to hear the story from inside,

Cause if not now, when will be the right time to discuss?” –A. Sheehy

A look into the minds and hearts of those who experienced an event no one, especially adolescents, should ever expect to encounter as they share with readers in similar and disparate circumstances across the globe.

On the first anniversary of the shootings at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, I read the writings of the survivors of that unspeakable event. In this “yearbook,” students and teachers share their stories of grief, terror, anger, and hope, and honor those who died through narratives, letters, speeches, free verse and rhyming poetry, and art. As the editor, MSD English and journalism teacher Sarah Lerner, writes, “Watching my students find their voices after someone tried to silence them was impressive…. It was awe-inspiring. It was brave…. They turned their grief into words, into pictures, into something that helped them begin the healing process.”

“[The news] keeps coming in,

It doesn’t pause

Or give you a break. It keeps hitting you

With debilitating blows, one after the other,

As those missing responses remain empty,

And your messages remain unread.” –C. Chalita

“We entered a war zone.…I came out of that building a different person than the one who left for school that day.” –J. DeArce

“Somehow, through the darkness, we found another shade of love, too

something that outweighed the hate and swept the grays away.

A love so strong it transcended colors, something so empowering and true it couldn’t be traced to one hue.” – H. Korr

“I just don’t want to let go of all the people I love,

I want to continuously tell them “I love you” until

My voice is raw and my throat is sore” – S. Bonnin

“I invite you [Dear Mr. President] to learn, to hear the story from inside,

Cause if not now, when will be the right time to discuss?” –A. Sheehy

A look into the minds and hearts of those who experienced an event no one, especially adolescents, should ever expect to encounter as they share with readers in similar and disparate circumstances across the globe.

Longoria, Margarita. Living Beyond Borders: Stories about Growing Up Mexican in America.

As Mexican-Americans, we have always needed to defend who we are, where we were born, and prove to others that we are in fact Americans." (Editor’s Intro)

The U.S. Hispanic population reached 62.5 million in 2021, up from 50.5 million in 2010. People of Mexican origin accounted for nearly 60% (or about 37.2 million people) of the nation's overall Hispanic population as of 2021. (Pew Research Center)

Twenty YA stories, essays, and memoirs in a variety of formats written by a variety of writers, some familiar to me, many new introductions, show “what it means to be Mexican American living in America today.”

Many teen readers will see themselves and their lives reflected in these stories, and many more will learn more about their Mexican American peers and the challenges they face in their homeland, America.

“I lie down and my mind races.…which gets me thinking about all the things that get white washed in America, which leads me to the border wall and people saying we need to keep the Mexicans out, which gives me all kinds of bad feelings because even though I’m not Mexican-Mexican, I am Mexican-American. Someone in my past came over.” (from Lopez, Diana. “Morning People.” 91-2)

As Mexican-Americans, we have always needed to defend who we are, where we were born, and prove to others that we are in fact Americans." (Editor’s Intro)

The U.S. Hispanic population reached 62.5 million in 2021, up from 50.5 million in 2010. People of Mexican origin accounted for nearly 60% (or about 37.2 million people) of the nation's overall Hispanic population as of 2021. (Pew Research Center)

Twenty YA stories, essays, and memoirs in a variety of formats written by a variety of writers, some familiar to me, many new introductions, show “what it means to be Mexican American living in America today.”

Many teen readers will see themselves and their lives reflected in these stories, and many more will learn more about their Mexican American peers and the challenges they face in their homeland, America.

“I lie down and my mind races.…which gets me thinking about all the things that get white washed in America, which leads me to the border wall and people saying we need to keep the Mexicans out, which gives me all kinds of bad feelings because even though I’m not Mexican-Mexican, I am Mexican-American. Someone in my past came over.” (from Lopez, Diana. “Morning People.” 91-2)

Mazer, Anne, ed. Going Where I’m Coming From: Memoirs of American Youth.

These fourteen memoirs about immigration and bridging cultures, are set in Watts, Hawaii, New York, Boston, Cleveland, San Antonio, NJ, the Standing Rock Sioux reservation, the San Joaquin Valley, and rural Alabama.

These stories of identity and self-discovery were written by such diverse authors as Luis Rodriguez, Ved Mehta, Thylias Moss, Naomi Shihab Nye, Lensey Namioka, and Gary Soto.

These fourteen memoirs about immigration and bridging cultures, are set in Watts, Hawaii, New York, Boston, Cleveland, San Antonio, NJ, the Standing Rock Sioux reservation, the San Joaquin Valley, and rural Alabama.

These stories of identity and self-discovery were written by such diverse authors as Luis Rodriguez, Ved Mehta, Thylias Moss, Naomi Shihab Nye, Lensey Namioka, and Gary Soto.

Perkins, Mitali, ed. Open Mic: Riffs on Life Between Cultures in Ten Voices.

Growing up "different" in the local culture is what the authors share in Open Mic—the stories, or “riffs on life,” of being culturally different. This is a book that should be in every MS/HS classroom, preferably a copy for every student to read, a collection that will generate important conversations about race and culture and fitting in, perhaps readers choosing a selection to read and discuss in small groups.

Written in a variety of formats—graphic stories, free verse, and prose—and in first and third person perspectives, memoir and fiction (or maybe fictionalized versions of memoir) by ten different authors, many who will be recognized by adolescent readers, there are stories that will appeal to all readers and are necessary for many adolescents. Many are hilarious; editor Mitali Perkins explains that humor is “the best way to ease…conversations about race” (Introduction), and all are enlightening. Truly, this is a collection of stories that serve as mirrors, maps, and windows.

Growing up "different" in the local culture is what the authors share in Open Mic—the stories, or “riffs on life,” of being culturally different. This is a book that should be in every MS/HS classroom, preferably a copy for every student to read, a collection that will generate important conversations about race and culture and fitting in, perhaps readers choosing a selection to read and discuss in small groups.

Written in a variety of formats—graphic stories, free verse, and prose—and in first and third person perspectives, memoir and fiction (or maybe fictionalized versions of memoir) by ten different authors, many who will be recognized by adolescent readers, there are stories that will appeal to all readers and are necessary for many adolescents. Many are hilarious; editor Mitali Perkins explains that humor is “the best way to ease…conversations about race” (Introduction), and all are enlightening. Truly, this is a collection of stories that serve as mirrors, maps, and windows.

Thomas, Annie, ed. With Their Eyes: September 11th: The View from a High School at Ground Zero.

“Journalism itself is, as we know, history’s first draft.” (xiii)

With Their Eyes was written from not only a unique perspective—those who watched the attack on the World Trade Center and the fall of the towers from their vantage point at Stuyvesant High School, a mere four blocks from Ground Zero, but in a unique format. Inspired by the work of Anna Deavere Smith whose work combines interviews of subjects with performance to interpret their words, English teacher Annie Thomas led one student director, two student producers, and ten student cast members in the creation—the writing and performance—of this play.

The students interviewed members of the Stuyvesant High study body, faculty, administration, and staff and turned their stories of the historic day and the days that followed into poem-monologues. They transcribed and edited these interviews, keeping close to the interviewees’ words and speech patterns because “each individual has a particular story to tell and the story is more than words: the story is its rhythms and its breaths.” (xiv) They next rehearsed the monologues, each actor playing a variety of roles. Although cast members were chosen from all four grades and to represent the school’s diversity, actors did not necessarily match the culture of their interviewees. They next planned the order of the stories to speak to each other, “paint a picture of anger and panic, of hope and strength, of humor and resilience” (7), rehearsed, and presented two performances in February 2002.

With Their Eyes presents the stories of those affected by the events of 9/11 in diverse ways. It shares the stories of freshmen, sophomores, juniors, seniors, special education students, an English teacher, a Social Studies teacher, the School Safety Agent, the Building Coordinator, a dining hall worker, a custodian, an assistant principal, and more, some male, some female, some named, others remain anonymous. Written as a play, readers are given a description of each character. Read and performed as a play, readers will experience the effect of Nine Eleven on others, actual people who lived that day and persisted in those days that followed, sharing their big moments and little thoughts. With Their Eyes was written with the thoughts and pens of a school community.

“Journalism itself is, as we know, history’s first draft.” (xiii)

With Their Eyes was written from not only a unique perspective—those who watched the attack on the World Trade Center and the fall of the towers from their vantage point at Stuyvesant High School, a mere four blocks from Ground Zero, but in a unique format. Inspired by the work of Anna Deavere Smith whose work combines interviews of subjects with performance to interpret their words, English teacher Annie Thomas led one student director, two student producers, and ten student cast members in the creation—the writing and performance—of this play.

The students interviewed members of the Stuyvesant High study body, faculty, administration, and staff and turned their stories of the historic day and the days that followed into poem-monologues. They transcribed and edited these interviews, keeping close to the interviewees’ words and speech patterns because “each individual has a particular story to tell and the story is more than words: the story is its rhythms and its breaths.” (xiv) They next rehearsed the monologues, each actor playing a variety of roles. Although cast members were chosen from all four grades and to represent the school’s diversity, actors did not necessarily match the culture of their interviewees. They next planned the order of the stories to speak to each other, “paint a picture of anger and panic, of hope and strength, of humor and resilience” (7), rehearsed, and presented two performances in February 2002.

With Their Eyes presents the stories of those affected by the events of 9/11 in diverse ways. It shares the stories of freshmen, sophomores, juniors, seniors, special education students, an English teacher, a Social Studies teacher, the School Safety Agent, the Building Coordinator, a dining hall worker, a custodian, an assistant principal, and more, some male, some female, some named, others remain anonymous. Written as a play, readers are given a description of each character. Read and performed as a play, readers will experience the effect of Nine Eleven on others, actual people who lived that day and persisted in those days that followed, sharing their big moments and little thoughts. With Their Eyes was written with the thoughts and pens of a school community.

Williams, Ismee and Balcarcel, Rebecca, eds. Boundless: Twenty Voices Celebrating Multicultural and Multiracial Identities.

The U.S. population is undergoing rapid racial and ethnic change. The multiracial population in the United States—those who identify with two or more races—is also increasing with the rise in interracial couples. The children of these interracial unions are forming a new generation that is much more likely to identify with multiple racial groups. By 2060, about 6 percent of the total population—and 11 percent of children under age 18—are projected to be multiracial. (Population Reference Bureau)

Most of us have felt, from time to time, that we don’t fit in—with our peers, our communities, our families, even our own skins—for a variety of reasons. These are twenty stories of adolescents who don’t feel they fit in or they are not “whole” because they are multiracial or multicultural. Boundless shares the multiracial and multicultural experience of contemporary adolescents.

Nina feels that she is not Asian enough to be a part of her extended family. “Sometimes I wonder of karaoke nights [with the family] would’ve felt different if I’d grown up where Dad did, around more people who looked like me. So many people in Hawaii are multiracial. It isn’t weird or different or ‘exotic’, like I’ve been called all my life.” (24)

Amalia Lipski is Hispanic-Jewish. “By trying to hold on to those two identities, I feel like I’m doing a disservice to both. Like, I’m trying to find the right balance, but I want to be more than fifty percent Judia and fifty percent Latina. I want to be two hundred percent everything. I want to be more than what everybody expects me to be. I want to be…perfect.” (42)

Tami is Japanese-Jewish. “I swore I wouldn’t…divide myself up. Not after I teacher called me half-and-half in elementary school…. Am I too much of something? Not enough of another? I know what I am not—whole.” (75)

Irene is Mexican-Irish, “EE-reh-neh to my mom’s side of the family (the Mexican side); Eye-reen to my dad’s side of the family (the Irish side)…. My goal in life is to keep my head down.” (85) “There is no way to divide myself and put the pieces into nice little boxes.” (96)

Eitan is Israeli-Mexican and feels invisible. “Was a person more defined by where they were born or where their parents were born? If some government or the other decided to take away either one of his nationalities, he would still be Eitan.” (124)

Madison Rabottini is Italian-Chinese. “There is nothing quite like doing a Zoom party with the Italian side of the family to realize how out of place my brother and I look in box after box of curly hair and hazel eyes. Then we flip to a Skype of my mom’s side, and suddenly Dad is the outsider.” (140)

Lydia is biracial, Indian-White. “There have been opposing forces within me for as long as I can remember. I am twins inhabiting the same body, two chemicals combined to form a unique reaction.” (277) “I am not Indian enough. Sometimes I don’t even feel American enough. I am not enough.” (280)

Simone is biracial; Sean is of Honduran decent, adopted by an Irish couple; Trevor is Black-Puerto Rican; Jerry is Filipino White; and, after his death, Hiba Ahmed visits her father’s homeland, Jordan. “I just want to know more about where he was from. About where I’m from.” “349

Here are stories for those who have not felt “enough” for any reason. As I wrote in my review for Black Enough, this is a book that invites some adolescents to see their lives and experiences reflected and invites others to experience the lives of their contemporaries.

The U.S. population is undergoing rapid racial and ethnic change. The multiracial population in the United States—those who identify with two or more races—is also increasing with the rise in interracial couples. The children of these interracial unions are forming a new generation that is much more likely to identify with multiple racial groups. By 2060, about 6 percent of the total population—and 11 percent of children under age 18—are projected to be multiracial. (Population Reference Bureau)

Most of us have felt, from time to time, that we don’t fit in—with our peers, our communities, our families, even our own skins—for a variety of reasons. These are twenty stories of adolescents who don’t feel they fit in or they are not “whole” because they are multiracial or multicultural. Boundless shares the multiracial and multicultural experience of contemporary adolescents.

Nina feels that she is not Asian enough to be a part of her extended family. “Sometimes I wonder of karaoke nights [with the family] would’ve felt different if I’d grown up where Dad did, around more people who looked like me. So many people in Hawaii are multiracial. It isn’t weird or different or ‘exotic’, like I’ve been called all my life.” (24)

Amalia Lipski is Hispanic-Jewish. “By trying to hold on to those two identities, I feel like I’m doing a disservice to both. Like, I’m trying to find the right balance, but I want to be more than fifty percent Judia and fifty percent Latina. I want to be two hundred percent everything. I want to be more than what everybody expects me to be. I want to be…perfect.” (42)

Tami is Japanese-Jewish. “I swore I wouldn’t…divide myself up. Not after I teacher called me half-and-half in elementary school…. Am I too much of something? Not enough of another? I know what I am not—whole.” (75)

Irene is Mexican-Irish, “EE-reh-neh to my mom’s side of the family (the Mexican side); Eye-reen to my dad’s side of the family (the Irish side)…. My goal in life is to keep my head down.” (85) “There is no way to divide myself and put the pieces into nice little boxes.” (96)

Eitan is Israeli-Mexican and feels invisible. “Was a person more defined by where they were born or where their parents were born? If some government or the other decided to take away either one of his nationalities, he would still be Eitan.” (124)

Madison Rabottini is Italian-Chinese. “There is nothing quite like doing a Zoom party with the Italian side of the family to realize how out of place my brother and I look in box after box of curly hair and hazel eyes. Then we flip to a Skype of my mom’s side, and suddenly Dad is the outsider.” (140)

Lydia is biracial, Indian-White. “There have been opposing forces within me for as long as I can remember. I am twins inhabiting the same body, two chemicals combined to form a unique reaction.” (277) “I am not Indian enough. Sometimes I don’t even feel American enough. I am not enough.” (280)

Simone is biracial; Sean is of Honduran decent, adopted by an Irish couple; Trevor is Black-Puerto Rican; Jerry is Filipino White; and, after his death, Hiba Ahmed visits her father’s homeland, Jordan. “I just want to know more about where he was from. About where I’m from.” “349

Here are stories for those who have not felt “enough” for any reason. As I wrote in my review for Black Enough, this is a book that invites some adolescents to see their lives and experiences reflected and invites others to experience the lives of their contemporaries.

Winchell, Mike. Been There, Done That: Writing Stories from Real Life.

Winchell, Mike. Been There, Done That: School Dazed.

In these two unique memoir collections, popular authors show how and where they get stories. Each author shares a real-life experience and the original fictional short story that event inspired.

Stories, relatable to readers everywhere, are divided into topics, such as dealing with peer pressure, putting others first, regret and guilt, change, morning school routines, class projects, and the dreaded school bus ride. Memoirists include well-known MG/YA authors Kate Messner, Julia Alvarez, Linda Sue Park, Lisa Yee, Alan Sitomer, Varian Johnson, Bruce Coville, and Meg Medina.

Winchell, Mike. Been There, Done That: School Dazed.

In these two unique memoir collections, popular authors show how and where they get stories. Each author shares a real-life experience and the original fictional short story that event inspired.

Stories, relatable to readers everywhere, are divided into topics, such as dealing with peer pressure, putting others first, regret and guilt, change, morning school routines, class projects, and the dreaded school bus ride. Memoirists include well-known MG/YA authors Kate Messner, Julia Alvarez, Linda Sue Park, Lisa Yee, Alan Sitomer, Varian Johnson, Bruce Coville, and Meg Medina.

BIOGRAPHY-MEMOIRS:

Bryant, Jen F. Feed Your Mind. Abrams Books for Young Readers, 2019.

“If you can read, you can do anything—you can be anything.”—Daisy Wilson

Frederick August Kittle Jr., the son of a white German baker and Daisy Wilson, a black single mother who left school after sixth-grade, cleaned houses, and taught her four-year-old Freddy to read, overcame racism and poverty to become a Pulitzer prize-winning playwright.

Freddy left school when prejudice from classmates made it evident that he, the only black student, was not welcome in Central Catholic High and teachers at the public high school doubted his writing genius. Besides his mother, only Brother Dominic had faith in him, “You could be a writer.”

Freddy educated himself at the Carnegie Public Library though the works of such black writers as Hughes, Dunbar, Ellison, and Wright and the conversations of the Hill’s tribal elders—“warriors who survive in this hard world.” His job as a poet, and later as playwright, was “to keep [these voices] alive” though a collage of black characters from the Pittsburgh that never left him.

Through Jen Bryant’s verse biography, readers follow Freddy Kittle’s daily life as he grows into August Wilson, influenced by black writers and collage artist Romare Bearden and supported by fellow playwrights. Feed Your Mind, a picture book for readers of all ages, but particularly MG/HS, is hauntingly illustrated by Cannaday Chapman and includes a Timeline, Selected Bibliography, and list of Wilson’s plays.

“If you can read, you can do anything—you can be anything.”—Daisy Wilson

Frederick August Kittle Jr., the son of a white German baker and Daisy Wilson, a black single mother who left school after sixth-grade, cleaned houses, and taught her four-year-old Freddy to read, overcame racism and poverty to become a Pulitzer prize-winning playwright.

Freddy left school when prejudice from classmates made it evident that he, the only black student, was not welcome in Central Catholic High and teachers at the public high school doubted his writing genius. Besides his mother, only Brother Dominic had faith in him, “You could be a writer.”

Freddy educated himself at the Carnegie Public Library though the works of such black writers as Hughes, Dunbar, Ellison, and Wright and the conversations of the Hill’s tribal elders—“warriors who survive in this hard world.” His job as a poet, and later as playwright, was “to keep [these voices] alive” though a collage of black characters from the Pittsburgh that never left him.

Through Jen Bryant’s verse biography, readers follow Freddy Kittle’s daily life as he grows into August Wilson, influenced by black writers and collage artist Romare Bearden and supported by fellow playwrights. Feed Your Mind, a picture book for readers of all ages, but particularly MG/HS, is hauntingly illustrated by Cannaday Chapman and includes a Timeline, Selected Bibliography, and list of Wilson’s plays.

Burkinshaw, Kathleen. The Last Cherry Blossom. Sky Pony, 2016.

All wars have two sides, but, as Winston Churchill said, “History is written by the victors.” Through history books and archives our students learn only one point of view, but we must disrupt the narrative with tales from the other side.

When our students study World War II—the war in Europe and the war with Japan, it is crucial that we help our students to see all perspectives and bear witness to the experiences of others. They need to learn that actions and decisions of governments have effects. One of those actions by the United States in 1945 was the bombing of Hiroshima, employing the first atomic bombs.

Through author Kathleen Burkinshaw’s poignant story, based on her mother’s childhood in Japan, readers can gain empathy and understanding for those innocent victims of war. This is the first-person narrative of 12-year-old Yuriko, her family members who are inundated with family secrets and shifting relationships, her neighbors who are sending their boys off to war, and her best friend. Through this important and well-written story, readers are introduced to Japanese culture, experience the strain of family secrets, and observe the war from the Japanese perspective. Not only a story of war, The Last Cherry Blossom is the story of family, heritage, and relationships.

All wars have two sides, but, as Winston Churchill said, “History is written by the victors.” Through history books and archives our students learn only one point of view, but we must disrupt the narrative with tales from the other side.

When our students study World War II—the war in Europe and the war with Japan, it is crucial that we help our students to see all perspectives and bear witness to the experiences of others. They need to learn that actions and decisions of governments have effects. One of those actions by the United States in 1945 was the bombing of Hiroshima, employing the first atomic bombs.

Through author Kathleen Burkinshaw’s poignant story, based on her mother’s childhood in Japan, readers can gain empathy and understanding for those innocent victims of war. This is the first-person narrative of 12-year-old Yuriko, her family members who are inundated with family secrets and shifting relationships, her neighbors who are sending their boys off to war, and her best friend. Through this important and well-written story, readers are introduced to Japanese culture, experience the strain of family secrets, and observe the war from the Japanese perspective. Not only a story of war, The Last Cherry Blossom is the story of family, heritage, and relationships.

Engle, Margarita. The Lightning Dreamer: Cuba’s Greatest Abolitionist. HMH Books for Young Readers, 2013.