- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

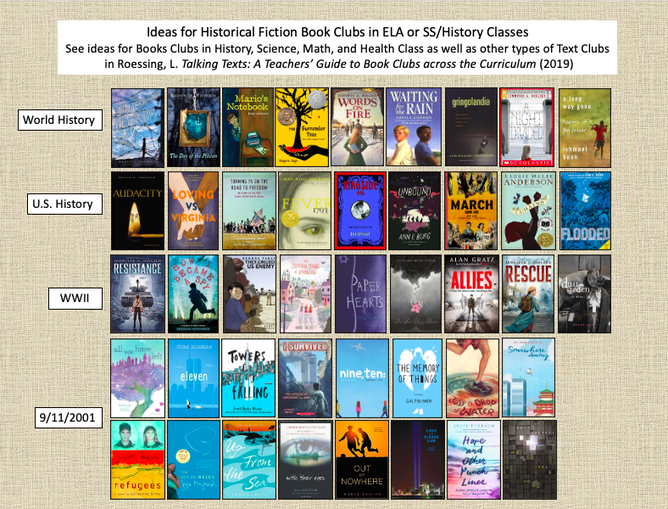

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

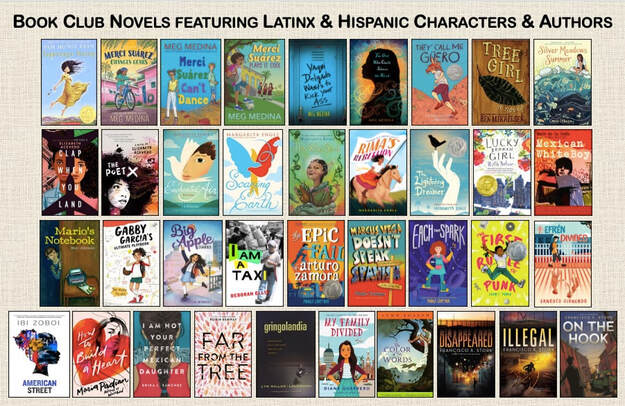

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

- Asian, Asian-American

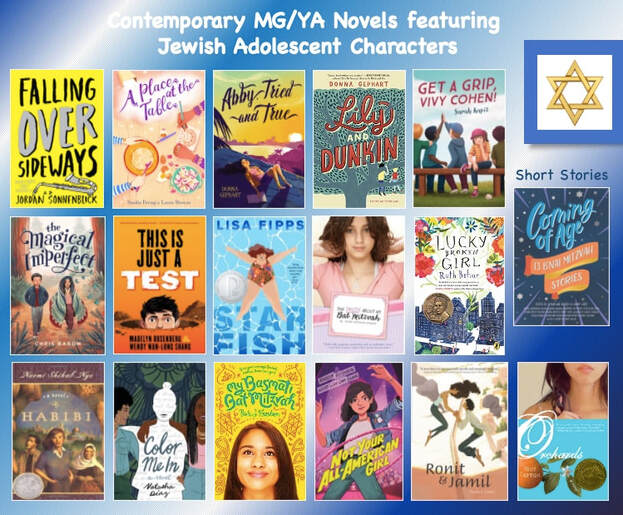

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

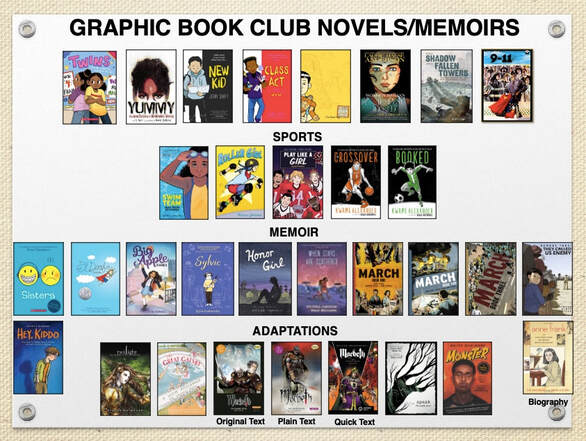

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

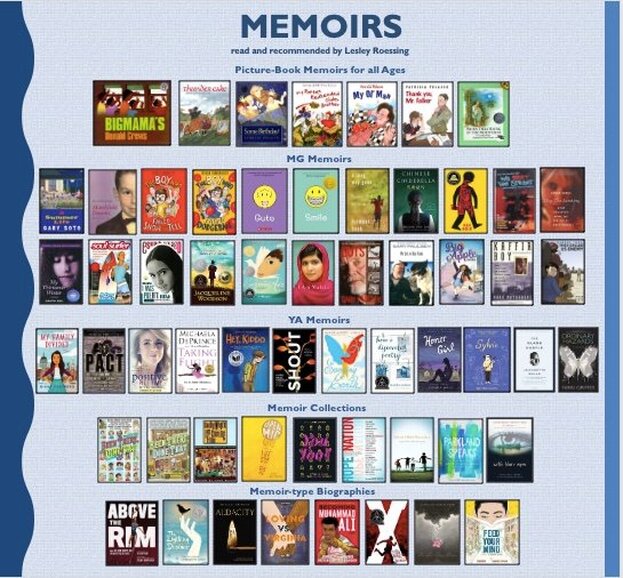

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

|

,My students were expected to read every day. The only requirement for reading in my ELA class was that readers choose books they could read and in which they were interested— not only in the topic, but also the author’s writing style. The classroom library and how we tended it nurtured our readers-choose philosophy. Sometimes we all read the same texts (whole-class, shared reading): poems, short stories, novels, and nonfiction articles and books; sometimes we read in book clubs (small-group, collaborative reading); and sometimes we all read different, self-selected books in the same genre (verse novels, graphic novels, nonfiction, memoir) or centered around a common theme or topic (the Holocaust, the environment). But most times (at least the last third of the year) my classes all read self-selected, choice books in any genre and length and on any topic. Because they were continually reading—during class Reading Workshop or at home for 25 minutes (see "Losing the Fear of Sharing Control: Starting a Reading Workshop"), my readers increased their interest in reading, their quantity and quality of reading, and their reading comprehension skills. I do not believe that readers themselves have a reading or Lexile level, but readers did increase their comprehension and interest in texts written at higher reading levels during the year. Readers get better by reading—not fake reading, not compliant reading, not SparkNotes reading, and not reading for testing—but reading for enjoyment and information. And finding books they love and want to read also grows lifelong readers. If teachers require, or reward, a certain number of books or pages to be read, readers will begin to choose shorter books at lower reading levels. Since my only requirement was that students read every day and write about what they read (see blog "The Importance of Reader Response"), there was no incentive to read books other than those that interested them. I remember when my some of my reluctant readers chose to tackled the Twilight series, books well over 400 pages, and others found authors such as Agatha Christie that they admitted were challenging for them (but worth the trouble)! Some readers obtained their books from bookstores, some from the local or school library, but most students—especially the reluctant readers—chose books from my classroom library. How I stocked and organized my classroom library became pivotal to our reading experience. One year, as we studied the literary term “genre,” I pulled books off my library shelves and asked students in pairs to read the covers and skim through the books, agree on a genre designation, and label the books with sticky notes. When they returned the books, neatly labeled, I decided to re-shelve the books by genre. A library that had gone nearly untouched suddenly had books flying off the selves. I realized that those readers who were not familiar with authors or titles knew topics that interested them. Given a few skimming guidelines, they could narrow the books down to the ones they most likely could, and would, read. It became important to have a balance of genres and topics on hand. I had to put aside my personal preferences and think of the tastes of my students, which varied from year to year. While I am not a fantasy enthusiast, several years, many of my students were fans. Luckily when I started teaching middle school, my own children—avid readers—were also adolescents and so, within a very few years, I had books I could add to the library. I became creative—I went to book sales, wrote grants for certain genres (such as a picture book grant and a memoir book grant), and picked up a lot of books in conference exhibit floors, such as National Council of Teachers of English. Many times at the end of conferences, exhibitors give away books so they do not have to cart them home. I attended the ALAN conference and was given forty new Young Adult books each year. I requested that students donate books to our library that they had bought and read but were not planning to read again and parents to donate books in their children’s names for birthdays. I did find out many adolescents don’t like books that look old or worn, so I did avoid yard sales but some of the libraries had sales of books that looked barely used. Some of my students became interested in reading classics and books such as the Agatha Christie mysteries; soon I was bringing in appropriate books from my personal library. I also borrowed books from our school library for weekly book passes and book talks to inspire students to check out these books on their own. In this way I was teaching the more reluctant readers to navigate a library that can seem overwhelming. My Criteria for Choosing Books: I looked for books that were well-written. This is not to say that we read Pulitzer-prize winning works, but one goal was to train reader-writers to read as writers. I wanted my readers to be able to notice good writing—especially devices and techniques we were discovering in writing workshop—to share examples with others and become more discriminating readers. Other Considerations in Choosing Books:

I usually did not spend money on series books that would fade quickly from fashion; however, at the time they were published, I invested in two copies of each of the Twilight books because so many of my reluctant female readers were devouring them. Therefore, it depended on my book, and personal, budget and how long books needed to last in popularity. ------ My Takeaway: As readers discovered favorite authors and favorite genres—memoir, historical fiction, sports fiction—and talked more about books with their friends, I would find notes on my desk on Fridays, “Mrs. R, If you are going to the bookstore this weekend, we would like ….” The classroom library truly became the students’ library filled with books they cared about and valued—and read. See texts (novels, memoirs, short writings, etc) that I have read, recommended, and reviewed by topic, theme, genre, and format under BOOK REVIEWS.

0 Comments

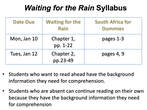

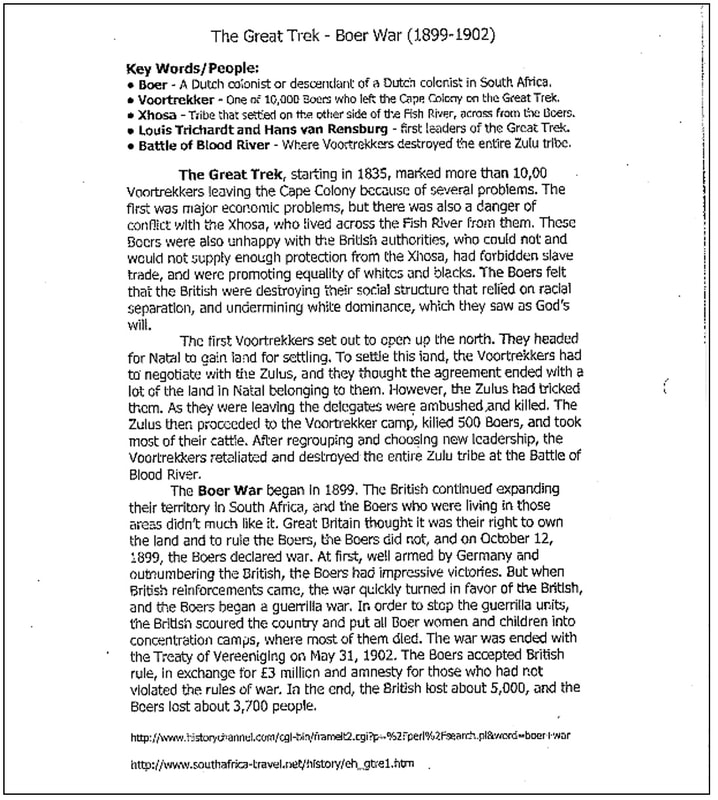

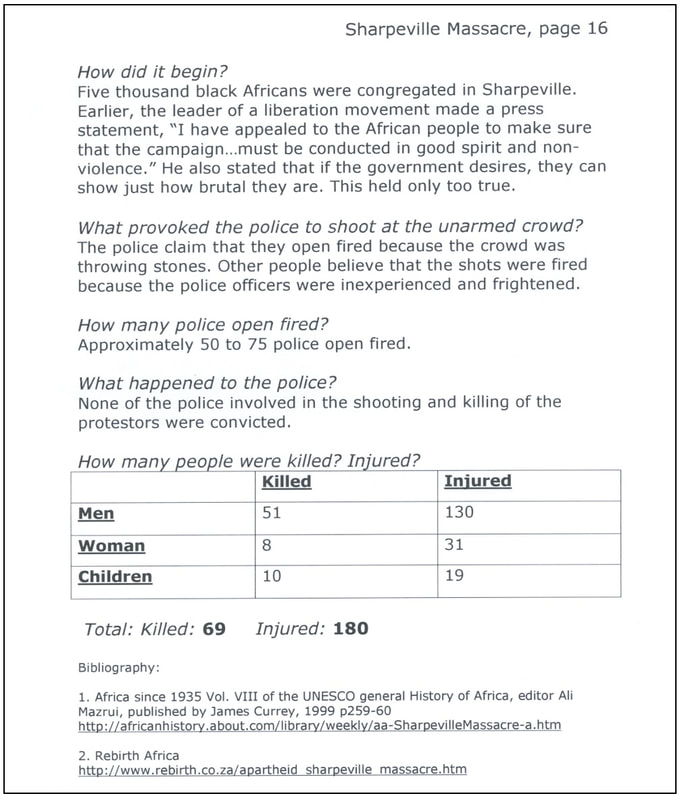

We were going the read Waiting for the Rain, a novel about Apartheid in South Africa, and my readers would need background information about Apartheid before, or as, they read this novel. It was a time period completely foreign to them. I also wanted my students to practice researching, taking notes, distilling information, and presenting that research to others although not orally. I had found that in the oral presentations, some of the class was going over their presentations in their heads, some were celebrating the fact that they had finished their presentations, presenters were using words and names unfamiliar to the class and which they would not recognize later, and, yes, some were listening, but would not remember the information when it was needed when reading they pertinent chapters in the novel. In addition, I wanted the class to be able to use that research. I wanted the research to matter. Most of the time when a student researches, two people benefit: the student-researcher and the teacher who reads the research paper or evaluates the research project. Since the adolescents were unfamiliar with Apartheid, they had no burning questions. More importantly, they would need the information from each other’s research when we began reading the novel. How could I make sure that their research was available for all to use? I thought about what I do whenever I come up against new knowledge that I need to learn and use, like learning Power Point. I go out and buy a book, a book that I, with no prior knowledge and little technical background, can understand. Many times I buy a Dummies guide. I bought The Dummies’ Guide to Power Point. And I put it on the bookshelf right next to The Dummies’ Guide to Wine and, yes, even The Dummies’ Guide to Shakespeare. With that thought, the idea was born! I decided that the class could write a guide to Apartheid to which all of us could then refer as we read the chapters of our novel. Not only would that solve the “usable” research quandary, but it would also solve my second research-based dilemma: how to teach students to avoid plagiarizing, even inadvertently. No matter how well-intentioned my students were, and no matter the number and variety of resources required, they still could not figure out how to put research into their own thoughts and words. What I wanted to teach them was to read the sources, conducting an investigation to find facts or discover theories that they would then write about with authority. One step towards that goal was to invite them to write for an audience of their peers (the “Dummies,” so to speak). They found that they had to evaluate the importance of facts found as well as needing to explain the information, sometimes using extra resources and talking to experts (other teachers). It no longer mattered that they previously knew nothing about the topics they were investigating. I have found that one has to be a learner to be a more effective teacher. The students’ goal became to write a resource that their classmates could understand and use as we read Waiting for the Rain. The class planned out their book; in this case, since I was familiar with the novel, I advised them what needed to be included. The students made up their Table of Contents and divided the topics. Next they brainstormed what text features make textbooks and resource material effective and user-friendly; they discussed titles, subheadings, glossaries, charts, maps, pictures, captions, graphs, and timelines as they looked through their textbooks and other nonfiction texts. They also identified formatting features: bold and italicized text, font choice and size, and justifications. South Africa for the Dummy was created. And written. The students were now not only researchers, but authors; they thought about their writing as authors think about writing—how it sounds, how it looks, and what it communicates. Once published, the guide was used. Everyone got a copy. We referred to Sarah’s pages when Frikkie’s uncle, Ooms Koos, mentioned the Boer War. When Joseph told Tengo about passbooks, we read Debbie’s pages about the Population Registration Act and Tom’s section on discriminatory laws. As the setting of the novel moved to Johannesburg, we looked at Amanda’s maps and John’s information on Jo’burg and the townships. We understood Joseph’s agony over the Sharpeville Massacre, and we knew of the work of Steve Biko even though he is not mentioned in the novel. For once, I was not doing the talking and the teaching; I was not spoon-feeding the information.  On their reading syllabus, it stated “February 10: “Soweto,” Dummy, p.24; Chapters 15-16, Waiting for the Rain.” We would refer to the articles (and authors) in class discussions. “Well, in his article on Nelson Mandela, Steve said that….” An added advantage was that students did not have to follow the syllabus. If they wished to read ahead, they now could; they had ready access to the background information necessary to comprehend the text. All authors’ research was being seen and valued by their classmates. The was no need to threaten grades or rewrites to elicit enough information or proper formatting or thorough editing; they were facing an even more critical audience—their peers. Teachers need to look for, and even create, opportunities for students to write for real audiences, audiences who care what is said and how it is written. In today’s world of email, text messages, and instant messaging, these occasions don’t readily occur. The following year some of the students returned from the high school to tell me that they had read Cry, the Beloved Country and used their Guide to more deeply understand that text and to study for the test. Our book demonstrated that research does matter. ADVANTAGES • Research skills for authentic use and audience • Makes every student an expert • Informative/Explanatory writing • Meta-cognition - analysis of Text Features and impact on individual learning styles • Independent research and individual writing for a collaborative project (small-group assignment for differentiation) Note: An advanced step required by CCSS is to study, analyze, and imitate text structures in mentor texts – compare/contrast, cause/effect, chronology, problem/solution, etc - and include in pages. This Blog was excerpted, revised, and updated from Roessing, L., Making Research Matter, The English Journal, Vol. 96, No. 4 (Mar., 2007), pp. 50-55

On my first day of teaching, I was given advice by a veteran teacher on his way out the door. “Five rows of six,“ he instructed, “not six rows of five.” Bob was advising me to keep my students apart, individual, independent, so it would be harder for them to talk to each other and to copy from each other. Twenty years later, when I was the veteran teacher walking out the door to move to university teaching, I left a classroom that not only was arranged in six rows of five, those rows were arranged in pairs so that each student always had a colleague with whom to confer and work, with easy access to two, three, or four others. I learned to always have a deck of cards ready to fan out for quick small-group selection and movement: "Group by Red cards, Black cards, Hearts, Diamonds, Aces, #’s, Evens, Odds…" Over the years I found the most powerful weapon for teachers at any grade level is collaboration. As teachers we need to keep in mind the ultimate goals of our classes: academic, all students learning, and affective, all students learning to work with others. And the best way to accomplish both is through collaboration and cooperation, students supporting students. In my middle-school English-Language Arts classroom, students wrote, read, spoke, planned and produced collaboratively. Collaboration, being social, provides motivation and engagement. I found that those students who would not produce work independently, at least did something—and learned something—supported by a partner or group. Learning and knowledge was extended. This strategy is in keeping with Aristotle: “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” ADVANTAGES OF COLLABORATION Collaborative projects become enhanced and improved with multiple perspectives, and students begin to appreciate and gain respect for those with knowledge, skills, and experiences divergent from theirs as they became interdependent through collaborative projects and common goals. In collaboration, each person’s contribution is crucial as students pool their resources and talents. The math wiz becomes revered in the ELA classroom when a group needs to design charts and maps; artists are fought over in almost every presentation utilizing design; and the musicians are wooed when persuasive writing includes commercials or grammar-rule songs are composed. And all students benefit from a convenient, engaged audience. Interdependency opens up possibilities of greater productivity, efficiency, and personal academic and affective growth as members of a group learn to collaborate in mutually beneficial ways and students learn the value of diversity and form a classroom community. An added benefit is the reduction of incidents of bullying when students widen their community, and classrooms are no longer divided into “Us” and “Them” as students gain respect for their classmates. Hopefully, that will spread an even wider net of respect and cause students to rethink their world. CONSIDERATIONS of COLLABORATION My students sat in pairs so they would always have a partner with whom to collaborate. Pairs could quickly turn their seats for groups of 4 or divide and move their seat across the aisle for triads. To mix up the partnerships each Monday students in the every other row (mixing it up each week) would move back one seat, giving them a new partner and, as they said, a new perspective of the classroom; students could also move to the right instead. The seats were fanned out as shown so that even the first students in the outside row could see other students instead of looking straight at the front and not feeling part of the community. At a workshop I was told how much time (I forget the number but it was staggering) over the year that we lose getting students into small groups. For small group work, many times students could choose their own groups. Some times I grouped students homogeneously and gave them slightly different activities or projects based on their skill and knowledge levels, and at times I grouped heterogeneously by abilities and talents. For random selection, I had a deck of playing cards. As students entered the classroom, they choose a card, fanned out in my hands, and I would announce, "All like numbers together," "All like suits together"; "All black cards together," based on the group size for the activity or project. Of course Book Clubs were grouped by book choice selection. With any group, it is vital to first teach social lessons. Teaching Discussion Strategies is Strategy #10 under my Reading Strategies section. COLLABORATION is a twenty-first century business skill. Collaboration reflects real-world businesses and situations where professionals collaborate on presentations, reports, and projects. Many businesses are now organized into teams rather than individual workers in departments; many office buildings—anticipating even more collaboration in the future—are no longer being configured into separate offices or cubicles. Where is education heading? My fear is that, with the emphasis on testing for individual scores and the continuous collection of individual data, as collaboration in the business world increases, it will decrease in the classroom. As it diminishes in the classroom, so will building classroom and school community, a sense of belonging, and a respect for diversity, reverting to a culture of “us” and “them.” It is imperative that teachers build collaborative communities in their classrooms to make school a safe and supportive place for children and adolescents. It is also essential that teachers help their students acknowledge that they belong to a group together, that they are part of a “we” or “us,” and that any differences—divergent talents, backgrounds, experiences, and skills—only make us stronger and better as they prepare students for a diverse future world. For examples of collaborative interdisciplinary reading-writing-speaking projects, such as The Home Front Fair, "You Were There" Holocaust books, The Cinderella Cultural Project, and more, see Research & Project Strategies in the Strategy Shorts drop-down menu.

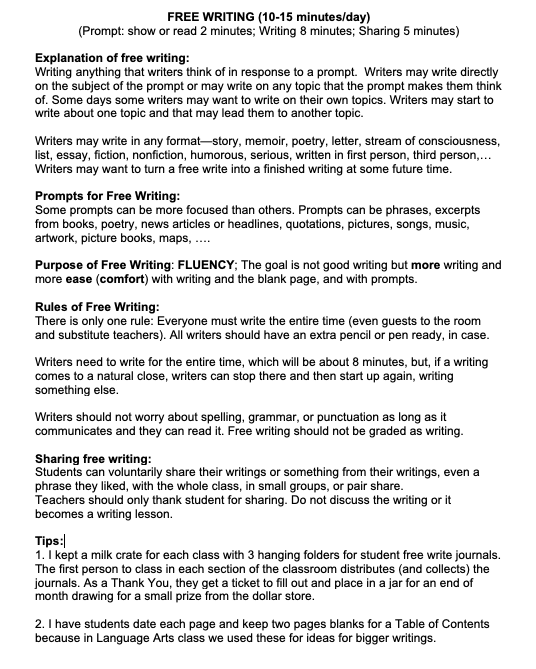

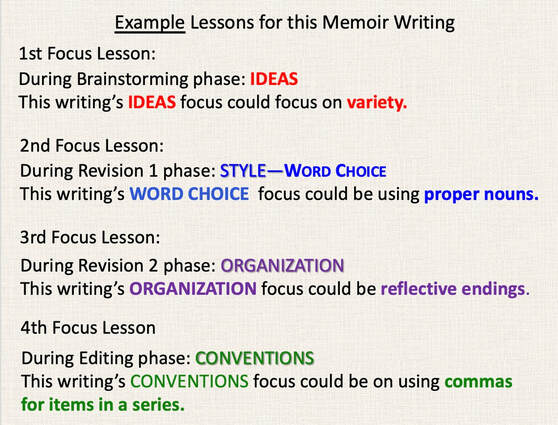

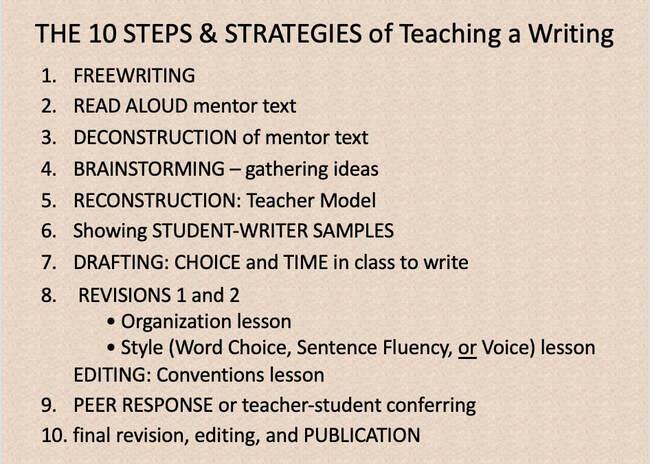

These are the 10 basic steps and strategies I use for teaching any writing. In this blog, I will take writers through a memoir writing as my example. STEP 1 FREEWRTING As explained in my Writing Strategy #1, FREEWRITING is writing anything that writers think of in response to a prompt. There is no way to freewrite incorrectly. Freewriting can be accomplished in any format—story, memoir, poem, letter, list, essay, stream of consciousness, fiction, nonfiction, humorous, serious, written in 1st, 2nd, or 3rd person,… . A prompt can be a word, a phrase, a quotation, a picture, an object, or music. The prompt should be as general as possible to allow for individual interpretation and writing on the prompt or leading pathways to tangents. One way I have found freewriting to be effective is to have writers freewrite for 4-8 minutes to generate ideas about the topic about which they will be writing to engage the writing brain cells and begin the writing process. Prompts should be as general as possible to allow for or encourage individual interpretation.

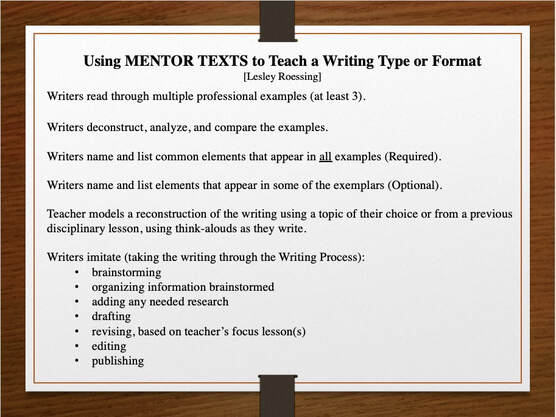

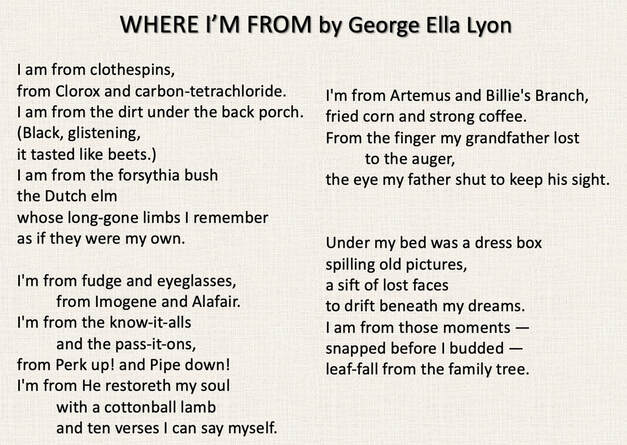

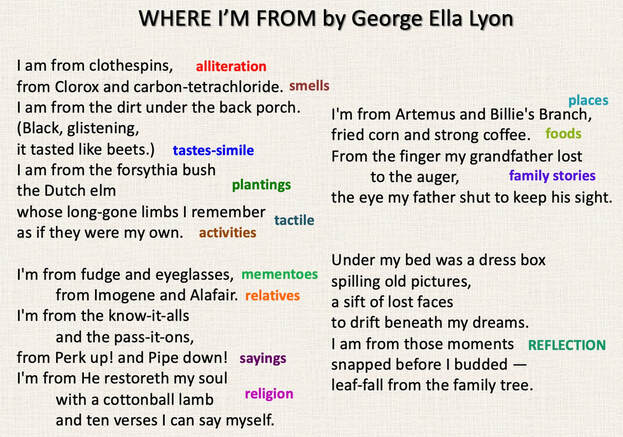

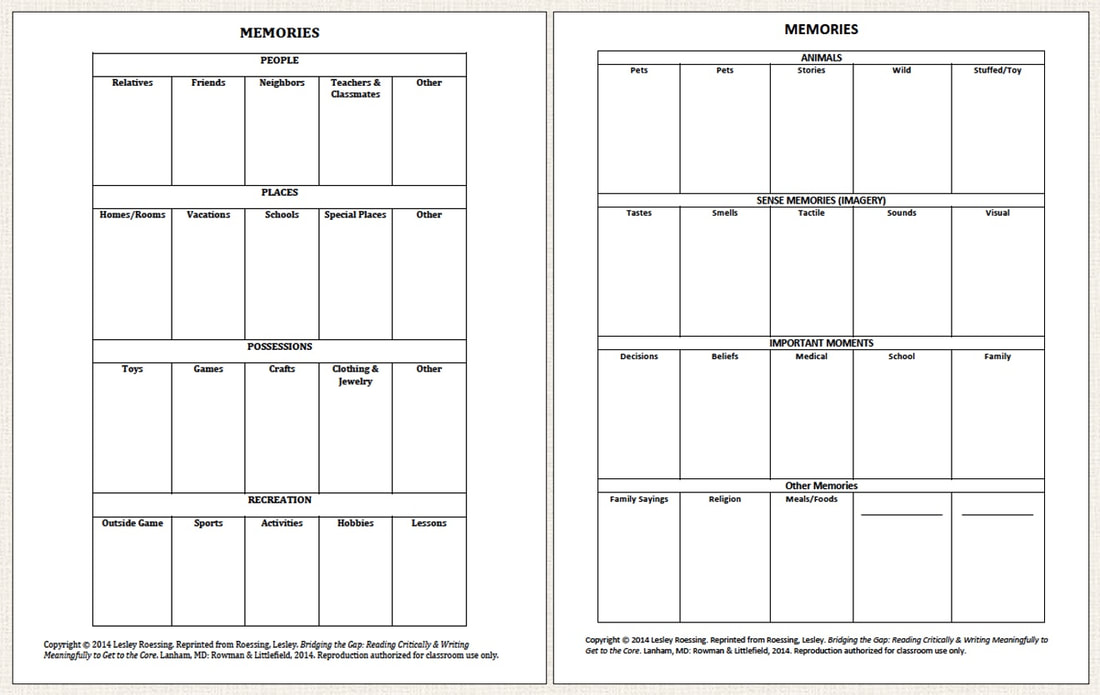

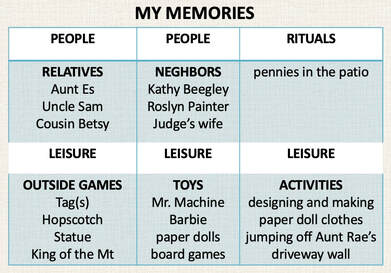

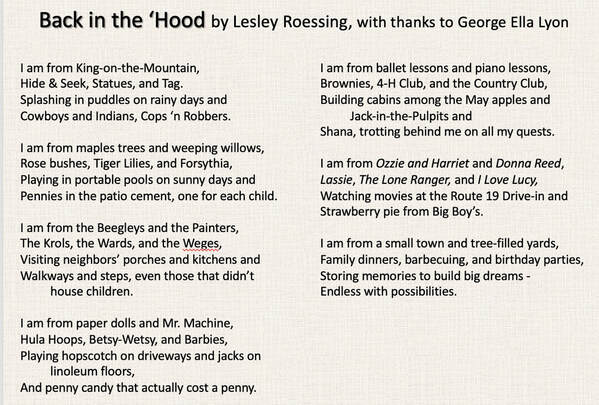

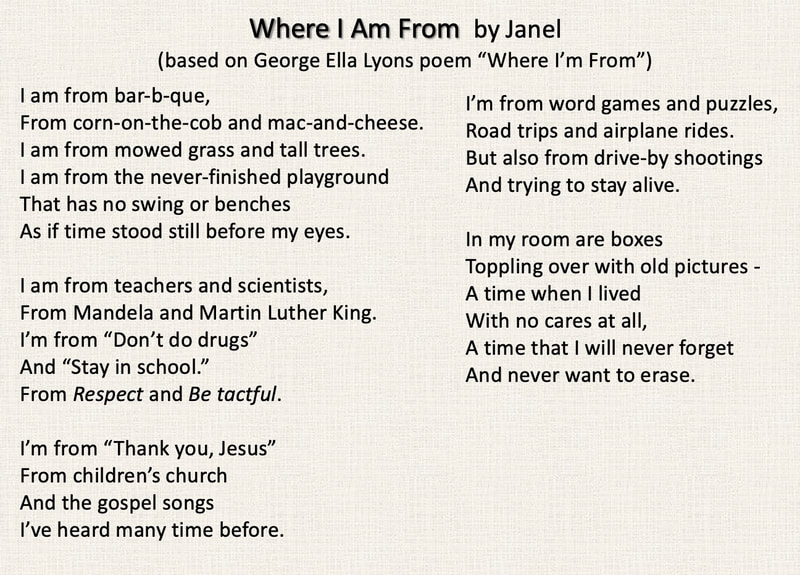

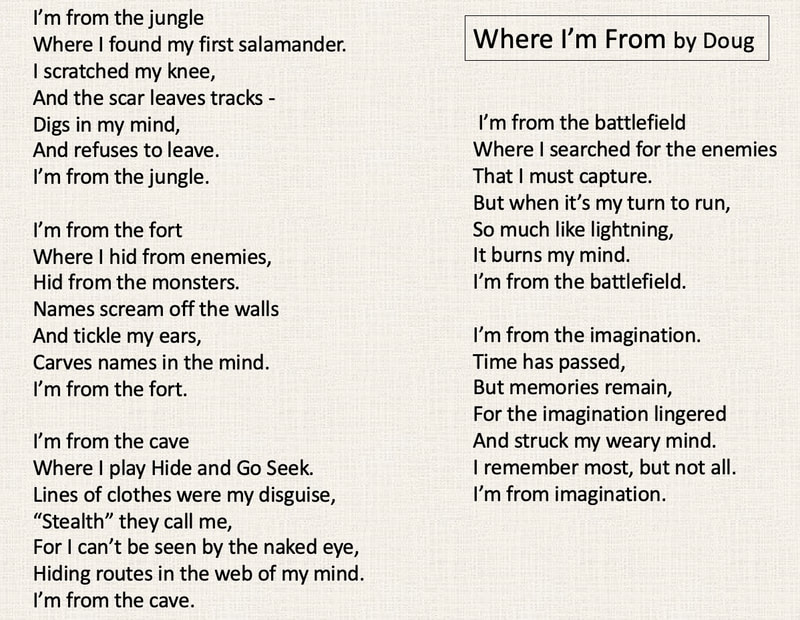

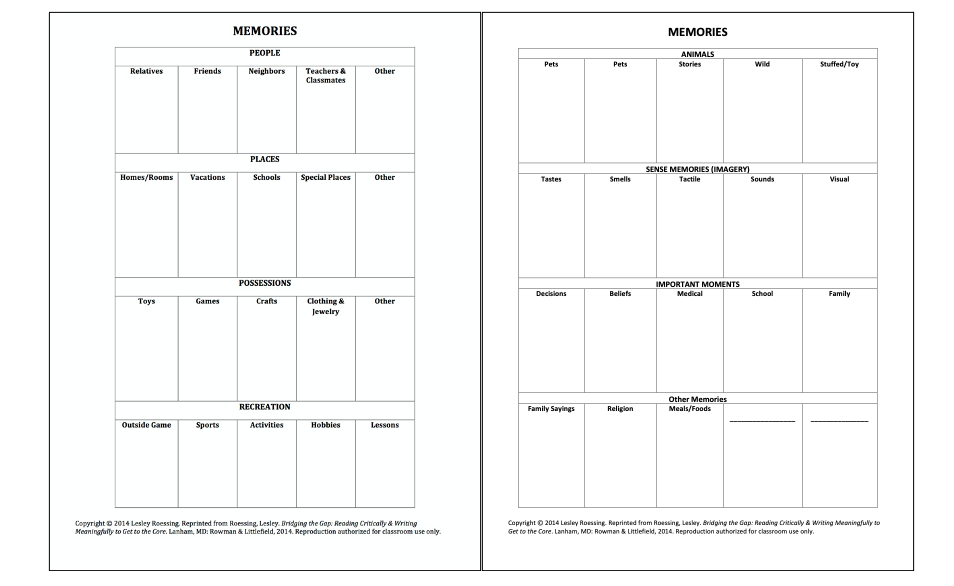

Writers may share their freewrites or parts of their freewriting which will lead to more ideas for other writers. STEP 2 READING ALOUD a MENTOR TEXT Writers read through multiple professional examples. In most cases I select and read aloud the first mentor text as an example of the writing students would be drafting (and as an exemplar of the form). One mentor text I employ for memoir writing is George Ella Lyon’s poem “Where I'm From.” STEP 3 DECONSTRUCTING the MENTOR TEXT Students are given a copy of the poem and after the teacher reads aloud the poem, students mark the poem with what they notice about the writing (writer’s craft) and the content. Writers can work in pairs or triads, annotating a copy of the poem. The class members then share what they observed as the teacher marks up a projected copy of the poem which may look like this: This activity gives writers ideas and choices of topics to include and writing crafts or literary elements to incorporate. After the class deconstructs and analyzes the first mentor text, the teacher may add 1-2 other mentor texts so that writers can compare and contrast the examples and determine, name, and list common elements that appear in all examples and note variations that different authors include, depending on teir writing style or their intended audiences. STEP 4 BRAINSTORMING I give writers a topic sheet to fill in to gather and activate their memories. S they filled in their sheets, I fill in mine on the white board, thinking aloud as I enter memories. Writers can ignore me or look up and acquire some ideas from my brainstorming. I tell students that

We take a break for writers to share some of their jottings with a partner or small group and then add some more as they glean ideas from others’ memories. STEP 5 RECONSTRUCTING a Text – Teacher Model After the class together deconstructs a mentor text and in pairs or small group, a few other examples, the teacher shows student-writers how writers take those elements and techniques from the mentor text and put them together, making it ours (synthesis). I ask writers to notice and share what I “borrowed” from Ms Lyon as my memoir-writing mentor and also how my writing differs from hers. Even though I employed some topics and ideas from the mentor text, I wrote in my own style. STEP 6 Showing STUDENT SAMPLES for differentiation If this is not my first year teaching this unit, I share some student samples from previous classes (with permission and without names). If teachers do not have student samples, Bridging the Gap includes examples from Grades 5 to 9 as well as Teacher Models. Students will note that some writers follow the mentor texts very closely while others are more creative. There is no “right” way even though teachers will want certain elements to be included as memoir writing, i.e., a reflective ending. However, we don’t want mentor texts to ever stifle creativity and individual voice. Showing a variety of examples also allows for differentiation. In these examples from Bridging the Gap (and my classroom), we see that Janel followed the mentor text very closely while Doug went in a completely different direction. STEP 7 DRAFTING Students now are ready to write a rough draft, consulting their brainstorming for ideas and referring to the mentor texts for content and form and organization. The most important aspects for successful writing are CHOICE and TIME. With the multiple mentor texts and examples, students have been given some CHOICE in what and how they write. It is vital to give TIME in class to write where they have the teacher and their peers for support and assistance. Also classrooms may house additional mentor texts and other supports for writing. STEP 8 REVISION and EDITING Focus Lessons Revision is the where teachers can teach good writing I teach one lesson (one element) for each writing domain or trait for each writing as students

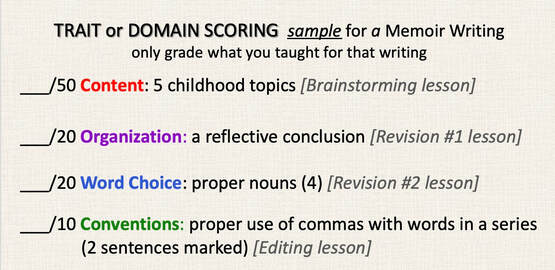

These lessons are taught as writing Workshop Focus Lessons:

See my blog on Gradual Release of Responsibility Lessons and various Strategy Shorts for Reading and Writing. I then use those lessons as my basis for assessment of that writing. Teachers can also use this as a formative assessment of what to teach or re-teach next. STEP 9 PEER RESPONSE GROUPS and/or or teacher-student conferring In groups of 3, authors read and peers respond to each other’s writings in a prescribed manner to help with revision. The Steps: 1. The Author introduces their writing. *The Author may have something particular they want help with. 2. The Author reads writing—entire piece or portion—to Responders who make notes on their copies (or on a piece of paper, if Author did not bring copies). 3. Each Responder shares:

STEP 10 Final revision and editing for PUBLICATION This is where writers might change their format of their drafts. ------------ TO RECAP: NOTE: Memoir Writing was shown only as an example. These 10 Steps & Strategies can be used, sometimes with some adaptations and modifications, for any writing, such as demonstrated as Writing Strategies #5 and #6 for Informative Writing which incorporates research.

We write for many reasons—to entertain, to inform, to persuade, to enlighten, to show what we learned, to find out what we know. But the most important reason our writers can write is to discover who they are and to reflect on the people, places, objects and mementos, and events that made them the persons they are and the adults they will become. In other words, memoir writing. As writers learn about themselves while “researching” and writing their memoirs, memoir writing becomes inquiry. And memoir writing becomes a journey of self-discovery. Why Teach Memoir Writing?

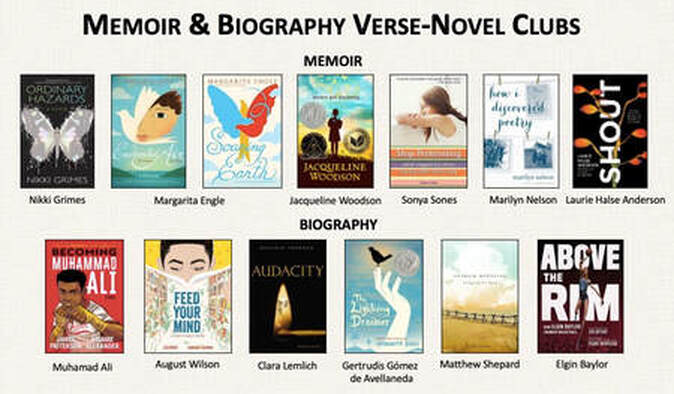

How to Teach Memoir Writing: Using Mentor Texts Like any writing, memoir writing is taught by first reading mentor texts. Memoir as a literary genre is experiencing great popularity, and memoirs are available in diverse reading levels and genres and on a wide variety of topics. There are memoir picture books, such as those written and illustrated by Patricia Polocco. There are memoir poems. i.e., George Ella Lyons “Where I Am From” which has developed into a genre of its own; Dolly Parton’s lyrics for “Coat of Many Colors” became a picture book (Parton, 1996); Cynthia Rylant’s free verse poetry collection about her home in Beaver, West Virginia, collected in Waiting to Waltz (2001). Graphic memoirs, such as Persepolis (Satrapi, 2004) or El Deafo (Bell, 2014), have become popular with many readers and writers. There are prose memoirs in essay length and novel length. And there are oral memoirs and video memoirs. Student writers read a memoir and analyze what the author wrote and how the author wrote, deconstructing those texts to discover how authors develop their writings. After the teacher demonstrates how to take those deconstructed elements and reconstruct them into a memoir, the students are ready to brainstorm their own topics and draft. I like to begin with an oral text, such as the Jerry Seinfeld’s “Halloween,” the story of Seinfeld’s childhood Halloween experiences and costumes. As the students listen to this memoir from the CD included in Seinfeld’s picture book Halloween (2008) or watch the story unfold on YouTube, they jot down the elements they notice, such as dialogue, narration, specific details, description, names and other proper nouns, humor, point of view, topics, humor, onomatopoeia, similes, reflection. After the class creates an anchor chart of elements effective for memoirs, students read a short written text to deconstruct. For example, looking at the first few lines of George Ella Lyon’s poem “Where I’m From” (1999), students are asked to note what they notice about what and how the memoirist writes. Charlie starts. “I notice smells, ‘Clorox and carbon-tetrachloride.’ I am not sure what carbon-tetrachloride is, but I am picturing a chemical smell.” We look it up and find out that carbon-tetrachloride was used in dry-cleaning establishments. A biography of Ms. Lyon reveals that her father worked as a dry cleaner, and students infer that either her father came home from work smelling of the chemical or she visited him at his business. Either way, that smell takes her back to her childhood. Another student chimes in, “Clothespins, Clorox, and carbon-tetrachoride are sort of like alliteration—almost the same beginning sound.” We talk about what activity the Dutch elm’s “long-gone limbs” suggests and infer that as a child, the author liked to climb that tree. Students observe that people’s names are included in the memoir, and a student says “Imogene and Alafair sound a little old-fashioned, so they could be parents or grandparents,” and others notice the family sayings, such as “Perk up.” We then share maxims from our own families. How to Teach Memoir Writing: Brainstorming and Drafting After noting that “Where I’m From” was created from a variety of childhood topics, such as people, places, events, activities, environment, religion, family sayings and stories, and foods, we all brainstorm topics from our childhoods, collecting them on a Memories Chart [see below] to help elicit ideas for writing. Using a projector I fill in my chart, relating a 1-minute story about each entry, as students fill in their charts. Some students glance up at my chart and listen as they become stuck; others stay focused on their own charts and tune me out. My demonstration is for those who need it. I clarify that not all the categories will have entries, and they need not fill in topics in any order. Over the next days as we read more mentor texts and share more personal stories, writers can add topics to their charts (Roessing, 141-142), gathering ideas for the memoirs they will write. As the next step I composes a short memoir employing some of the same elements and techniques that we have noticed in our two mentor texts. Since at this point we have only heard Jerry Seinfeld’s monologue and read George Ella Lyon’s memoir, I draft my memoir, following much of the poet’s structure and employing many of her techniques, adding a few elements from our analysis of “Halloween.” I am from King-on-the-Mountain, Hide & Seek, Statues, and Tag, Calling out “I’m It” or “I win!” And splish-splash-ing in puddles on rainy days. I am from maples trees and weeping willows, Big back yards, each with a swing set and sandbox, Playing in portable pools on sunny days and Putting pennies in the patio cement as we build our porch.… Students then analyze my memoir, noticing how it employs topics, literary elements, and some writer's crafts from the mentor texts but also how it differs to reflect my memories and writing style. Over the next few days I introduce the students to other memoir mentor texts while they read full-length self-selected memoirs* either independently or in book clubs, add topics to their lists, expand the class anchor charts, and draft short memoirs in a variety of formats—prose, different styles of poetry, and graphic—shadowing the exemplars read. After students have sufficient ideas and content and they are ready to choose the topic(s), types, and formats for one of their memoir drats to take to the publishing stage (or more in a longer unit), they revise based on daily revision mini-lessons on the traits—organization, word choice, voice, sentence fluency, and finally edit based on convention lessons taught in class. An important focus lesson we will cover is the reflection that generally comes at the end of a memoir. We again look at mentor texts. We examine the ending of “Where I’m From” as well as endings to prose memoirs, such as Cynthia Rylant’s When I Was Young in the Mountains (1993). When I was young in the mountains, I never wanted to go to the ocean, and I never wanted to go to the desert. I never wanted to go anywhere else in the world, for I was in the mountains. And that was always enough. (last page) One student combines our lessons in her final memoir (Roessing, 2014, p. 77-78): "Where I Am From" by Janel (based on G.E. Lyon’s poem “Where I’m From”) I am from bar-b-que, From corn-on-the-cob and mac-and-cheese. I am from mowed grass and tall trees. I am from the never-finished playground That has no swing or benches As if time stood still before my eyes. I am from teachers and scientists, From Mandela and Martin Luther King. I’m from “Don’t do drugs” And “Stay in school.” From "Respect" and "Be tactful." I’m from “Thank you, Jesus” From children’s church And the gospel songs I’ve heard many time before. I’m from word games and puzzles, Road trips and airplane rides. But also from drive-by shootings And trying to stay alive. In my room are boxes Toppling over with old pictures - A time when I lived With no cares at all, A time that I will never forget And never want to erase. While this writer followed Lyon's format somewhat closely, others had the confidence to move in divergent directions. Conclusion I have not included much about the drafting phase because the memoirs almost write themselves. If teachers help adolescents to think back and remember and reflect on their pasts through reading the memoirs of others and sharing their childhood stories within the classroom writing community, after analyzing texts and brainstorming, stories pour out. I am always amazed that this is one unit for which all my students have written and all have done their best writing of the year. Students have written about persons, places, mementoes, events, crises, and discovered photographs. Writers have published their memoirs as rhyming poems, free-verse poetry, limericks, sonnets, prose narratives, plays, and graphics. They have shared unbelievably personal stories, such as “The Day Daddy Left,” and humorous stories, such as “Beastie.” But most importantly, adolescent writers have perceived themselves as authors as they wrote with voice, cared about their writing, and discovered meaning in their lives as they learned about themselves, writing what matters.  More teacher models, student examples (along with lessons, mentor texts, and reproducible forms for brainstorming) can be viewed in Bridging the Gap: Reading Critically & Writing Meaningfully to Get to the Core. *Memoir Reading while Memoir Writing How is memoir writing supported by memoir reading? Reading memoirs provides mentor texts for writing memoirs. As readers read about people, places, objects, and events which are meaningful to published memoirists, they can notice and note how the memoirists write about these topics, using authors as mentors for their writings. Memoirs appeal to all readers because they are available at all reading levels and lengths; on all topics from dancing to sports to survival and resilience; in many formats, including prose, free verse, graphic, multi-formatted, and even as rhyming poems. Memoirs are written in first and third person, and can be humorous, poignant, and enlightening. Readers can together read whole-class memoirs, participate in memoir book clubs or memoir essay clubs, and read self-selected memoirs individually. In addition to memoirs, there are novels, such as Front Desk, that closely follow the author’s life, and there are biographies written in the style of memoir in that they focus on a particular part of a person’s life or particular events based around a theme and emphasize personal experience, thoughts, feelings, reactions, and reflections rather than facts.  Picture Book Memoirs: Bigmama’s; Patricia Polacco’s memoirs; When I Was Young in the Mountains ES/MG Memoirs: A Summer Life; Marshfield Dreams; The Boy Who Failed Show and Tell; The Boy Who Failed Dodgeball; Guts; Smile; A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier; Chinese Cinderella; Free Lunch; We Beat the Streets; Stop Pretending: What Happened When My Big Sister Went Crazy; My Thirteenth Winter; Soul Surfer; When I Was Puerto Rican; Brown Girl Dreaming; Enchanted Air; I Am Malala; Guts; My Life in Dog Years; Big Apple Diaries; Kaffir Boy; They Called Us Enemy YA Memoirs: My Family Divided; The Pact; Positive; Taking Flight; Hey, Kiddo; Shout; Soaring Earth; How I Discovered Poetry; Honor Girl; Sylvie; The Glass Castle; Ordinary Hazards Memoir Collections: Been There, Done That; Going Where I’m Coming From; Open Mic; You Too?; Hope Nation; When I Was Your Age; Parkland Speaks; With Their Eyes: September 11th—The View from a High School at Ground Zero Memoir-type Biographies: Above the Rim; The Lightning Dreamer; Audacity; Loving vs Virginia; Becoming Muhammad Ali; X; The Last Cherry Blossom; Feed Your Mind References

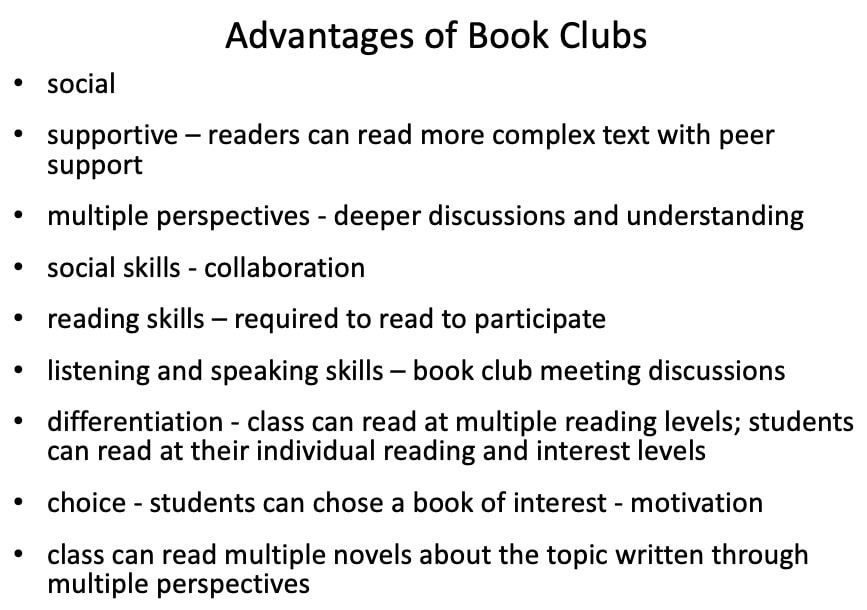

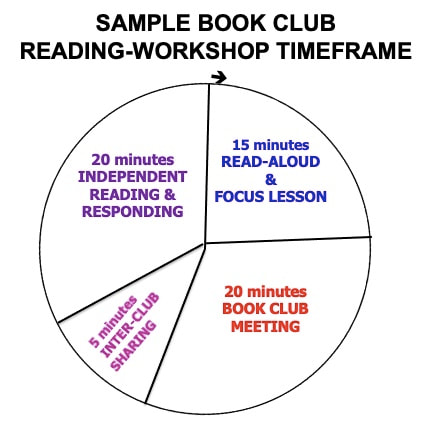

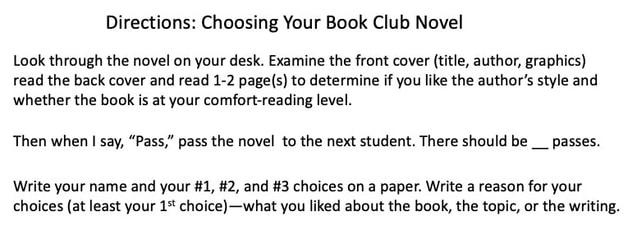

Bell, C. (2014). El Deafo. New York: Harry N. Abrams. Lyon, G.E. (1999) Where I’m from. Where I’m from: Where poems come from. Spring, TX: Absey & Company. Moore, J. (2014). Where I am from. As in Roessing, L. Bridging the gap: Reading critically and writing meaningfully to get to the core. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Parton, D (1996). Coat of Many Colors. New York: HarperCollins. Roessing, L. (2014). Bridging the gap: Reading critically and writing meaningfully to get to the core. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Rylant, C. (2001). Waiting to waltz. New York, NY: Atheneum/Richard Jackson Books. Satrapi, Marjane. (2004). Persepolis: The story of a childhood. New York, NY: Pantheon. Seinfeld, J. (2008). Halloween. New York, NY: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers. The ideas and examples for this article were based on Bridging the Gap: Reading Critically and Writing Meaningfully to Get to the Core. In a gradual-release-of-responsibility model of teaching reading, this would be about the time of the school year that teachers are moving from whole-class short stories (to teach or review reading strategies, literary elements, and author’s craft [see Reading Strategy #6]) and whole-class novel(s) [see Reading Strategy #9] to reading in BOOK CLUBS in the move toward independent, self-selected reading [see “Losing the Fear of Sharing Control”]. Of course Book Clubs can be held any time, and my students always clamored for "one more Book Club" in the midst of independent reading. I have facilitated BOOK CLUBS in Grade 3 though university classes in English-Language Arts and content area classes. I have written extensively about the benefits of reading in BOOK CLUBS. And I have written about holding TEXT CLUBS to read poetry, short stories, folktales, nonfiction books, articles, and textbook chapters in collaborative small groups. For strategies, lessons, assessments, models, and reproducible forms, see TALKING TEXTS: A Teacher’s Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum. These are my 5 basic steps for facilitating any type of BOOK CLUB (or TEXT CLUB). 1. SETTING UP BOOK CLUBS

2. TEACHING SOCIAL/DISCUSSION SKILLS

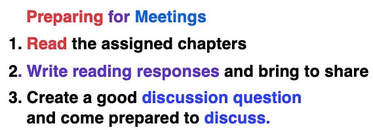

3. TEACHING BOOK CLUB PROCEDURES

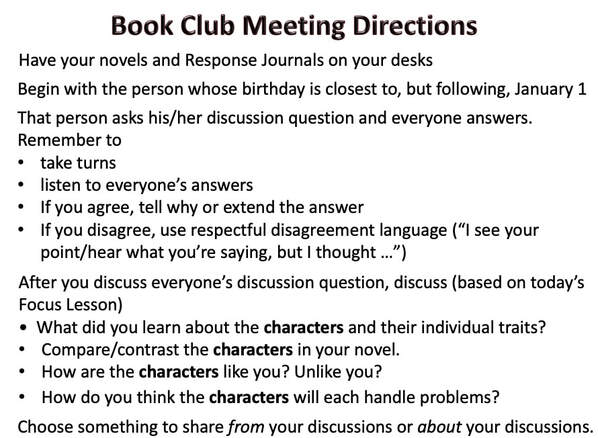

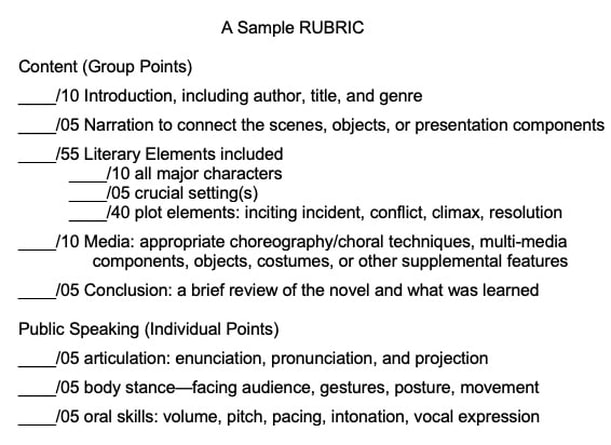

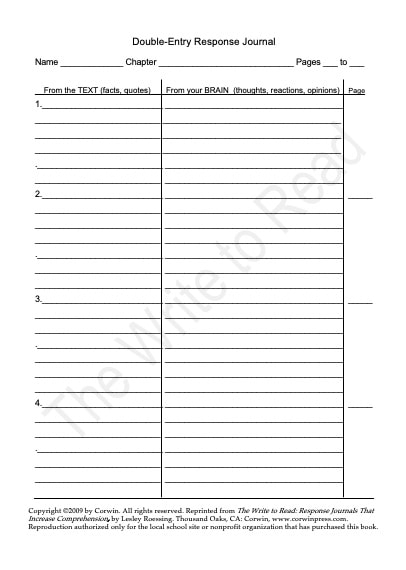

4. FACILITATING BOOK CLUB MEETINGS This is one class sample directions; the day's Focus Lesson centered on character traits) 5. ASSESSMENT a. READING: I assessed reading based on their Reader Response journals which they used for their discussions (see TALKING TEXTS and THE WRITE TO READ for my lessons and reproducible forms). b. MEETINGS: I assessed meetings by observations and by student self-assessments c. PRESENTATIONS: My GUIDELINES:

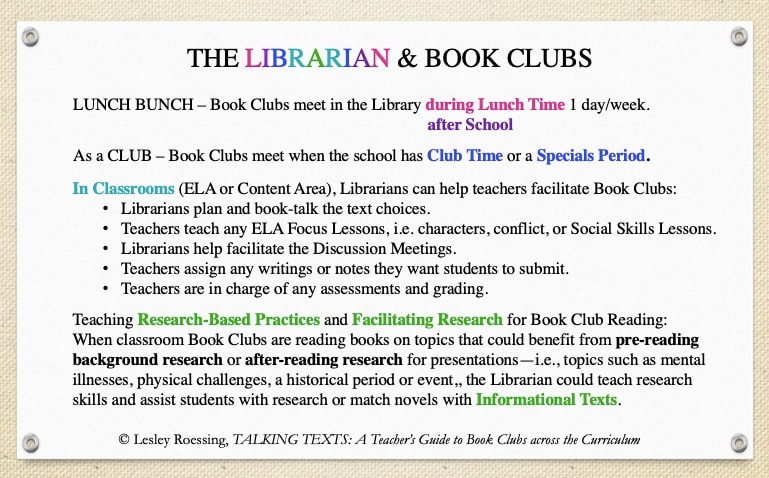

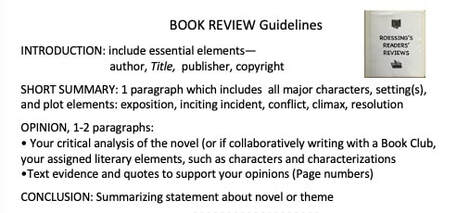

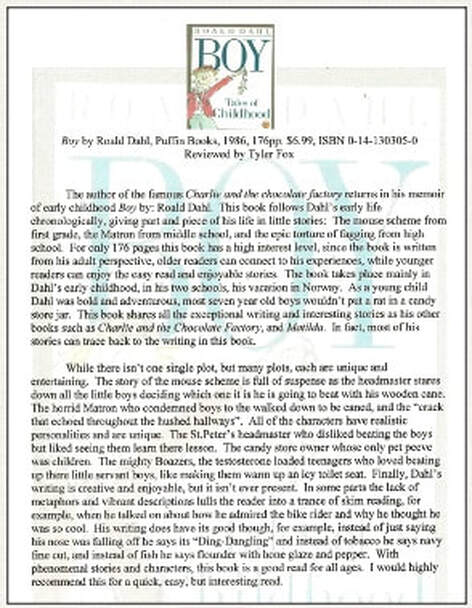

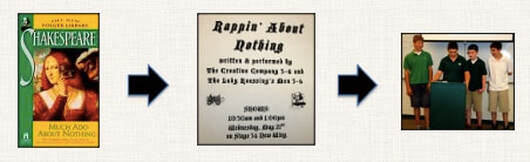

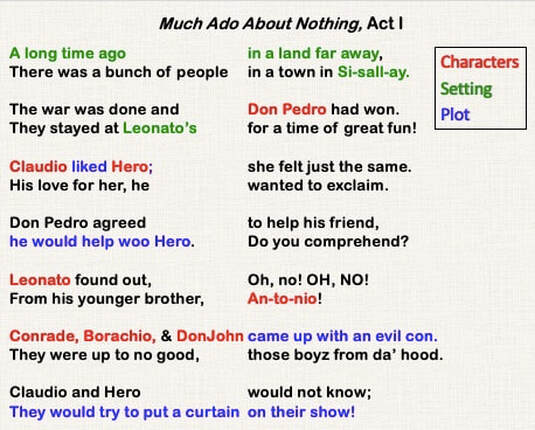

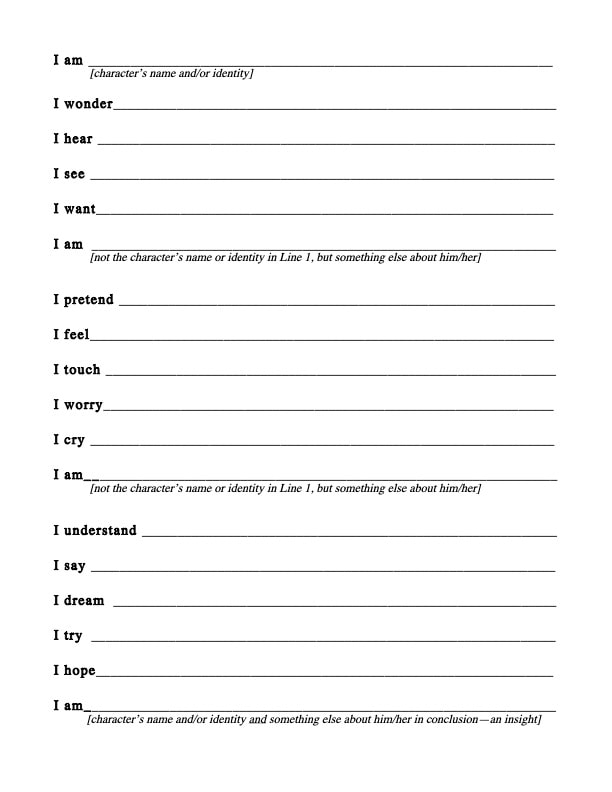

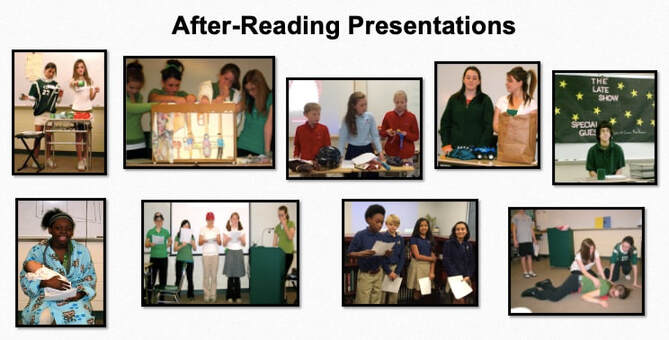

A percentage of the grade was based on the content of the group presentation and a percentage was based on individual speaking points. My typical BOOK CLUB Schedule, a sample: WEEK 1-- Monday: discuss Book Club expectations, Social Skills Focus Lesson, Book Talks and Book Passes Tuesday: Discussion Lesson (Strategy #10); distribute novels; Book Cubs meet to plan reading Wednesday: Creating Discussion Questions Lesson; Reading Time Thursday: Lesson on Book Club Procedures; Reading Time Friday: review Discussion or Social Skills Focus Lesson; Book Club Meeting #1 WEEK 2-- Monday: Literary Focus Lesson; Reading Time Tuesday: Literary Focus Lesson; Book Club Meeting #2 Wednesday: Literary Focus Lesson; Reading Time Thursday: Literary Focus Lesson; Reading Time Friday: Literary Focus Lesson; Book Club Meeting #3 WEEK 3-- Monday: Literary Focus Lesson; Reading Time Tuesday: Book Club Meeting #4 and Reading Time Wednesday: Literary Focus Lesson; Reading Time Thursday: Book Club Meeting #5 Friday: Lesson on Presentation Choices and Expectations; Public Speaking Lesson WEEK 4-- Monday and Tuesday: Book Clubs works on Presentations Wednesday; Class Presentations And strategies for LIBRARIANS who wish to start or work with BOOK CLUBS:  TALKING TEXTS: A Teacher's Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum includes classroom strategies, focus-lessons, and reproducible forms for facilitating, organizing, integrating, and assessing collaborative, small-group reading and teaching effective, supportive discussion techniques in Grade 3 through university classes—strategies that work for all types of text: novels and memoirs, short stories, informational texts and articles, poetry, folktales, and even textbooks in all content areas. In my last blog, “The Importance of Reader Response,” I explain the value of READER RESPONSE and how response compels readers to interact with the text and makes visible for readers and their teachers the depth (and type) of text comprehension. I share strategies, activities, teacher models, and student examples for a variety of types of before and during-reading response. This blog will focus on the importance of AFTER-READING RESPONSE in all content areas. I cannot overstate the importance and advantages of returning to the text for synthesis. In synthesis, learners put together assorted parts to create a new whole, expanding understanding.I find that every time I reread a text, I create expanded, enhanced, and even more innovative interpretations, making the text more interesting and learning more from the text. Students notice this also and tell me, “I learned more this time” or “I never noticed that.” But how can we encourage students to return to the text—connecting the parts and responding to the writing as a whole—to construct or develop new ideas. When I finish a book, I may not build a project out of materials, but I do create a way to understand what I have read and the meaning of my understanding in my mind. As reflective reader I consider, or even discuss with others, my reading and the significance of what the author has said. I mull over the text, compare notes with other readers, and mentally contrast the text with other texts, either written by the same author or other writers. Sometimes I even compare the book with a movie based on the book. And that is what we need to do as teachers; we need to train our students to return to texts to question, interpret, compare, and analyze. If this process starts in school, it becomes internalized as students become better, highly- skilled readers. (The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension) I will describe different types of after-reading activities that not only promote synthesis of texts read, but share meaning created and, in the case of book club and individual reading, share texts with others. BOOK REVIEWS One of the most effective ways to teach readers to analyze books read (and teach critical thinking and argument writing) is through student Book Reviews which can be collected in a binder or on a website for access to other readers who are looking for reading ideas. I scaffolded Book Review writing through the year: Each marking period my readers were required to write a formal BOOK REVIEW (meeting multiple reading and argument writing standards). MARKING PERIOD 1: The CLASS first analyzed 3 published book reviews (NY Times, local paper, and from old copies of NCTE's Voices from the Middle) as mentor texts, deconstructing and noting elements that were included in ALL reviews and elements included in only SOME reviews. The "All" became required elements for their reviews; the "Some" were optional. I required a certain number of "optional" elements, differentiating for different students. The class then wrote a review together, critiquing our whole-class novel. Students brainstormed ideas together, collaborated on appropriate language, and then readers wrote individual reviews (or in pairs), using as much from the class discussions as they wished. MARKING PERIOD 2: Book Club members collaborated on a Book Review, critiquing their Book Club novel, each member analyzing a different literary element. MARKING PERIODS 3 and 4: Readers Individually choose 1 of their self-selected, independently-read texts to review. Reviews were typed and illustrated, usually with a picture of the cover, and housed in the Roessing Readers' Reviews binder which was divided by genre (as was our classroom library) for readers to peruse when looking for a next book to read. √These also could be uploaded to a class, teacher, or library computer as a digital binder. Pictured are my GUIDELINES FOR REVIEWS and a student Book Review from The Write to Read. See The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension and Talking Texts: A Teachers' Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum for more student samples and other ways readers shared their readings, individually and collaboratively. TEXT REFORMULATIONS I have found the best way to encourage students to return to the text is to ask them, as their after-reading response, to turn the text into a different format (reformulation), which can be applied to whole-class, small-group, or individual, self-selected readings. Each rereading of a text gives readers a greater and deeper understanding, making them better readers and increasing comprehension. Texts reformulations can be created and presented individually or in groups. And text reformulations can encourage the engagement of multiple intelligences: linguistic, mathematical, musical, spatial, kinesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and environmental. 1. RAPPING A TEXT Students read, performed, and discussed a Shakespearean play. After, they formed five groups; each group selected one act. The groups turned their acts into a rap, with the requirements to include all the major characters, settings, and important plot elements that occur in that act. They then performed their raps for the class utilizing public speaking techniques such as eye contact, enunciation, voice projection, and other choral reading techniques. After going back to the text to determine characters, setting(s), and analyzing the most important events in their acts, readers again went back and forth to the original text repeatedly, translating Shakespearean English to modern English to rap English and playing with rhyme. Students were so engaged with the activity and the product that they asked teachers in their other classes to release them to attend the performance of my other Humanities class, to listen to their raps. There are other students samples of reformulating texts into narrative poems, enhancing summarization skills, in The Write to Read. 2. FOUND POETRY Found poems take words, phrases, and details from existing texts and require readers to modify them, reorder them, and present them as poems, much as one does when creating a collage, resulting in learning and showing understanding in new ways. In the interest of true synthesis and showing one’s learning, I suggest that the found poetry employed in after-reading response writing include some of the reader/writer’s own thoughts about the text. Other decisions of form, such as where to break lines and spacing, are also left to the poet. (Roessing, “Using Found Poetry for Synthesizing Text,” AMLE Magazine) These are my directions:

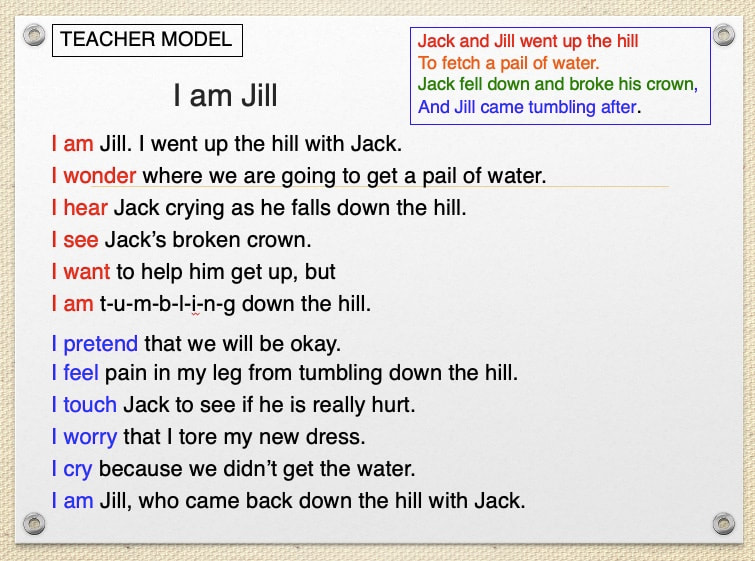

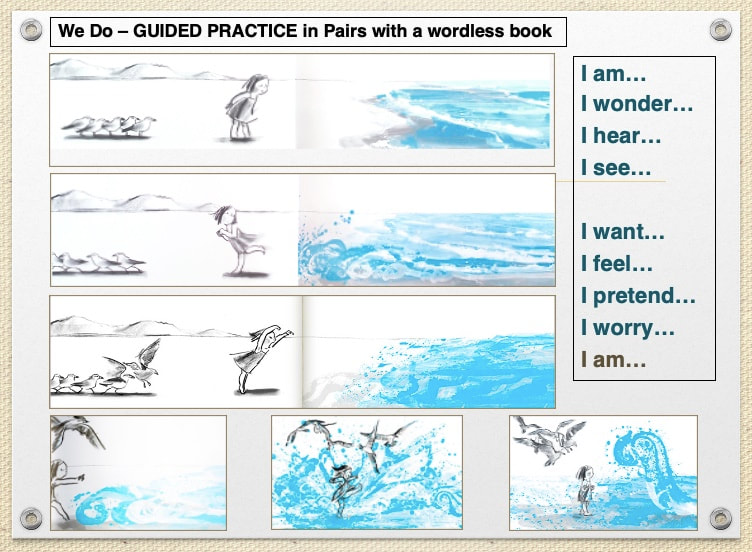

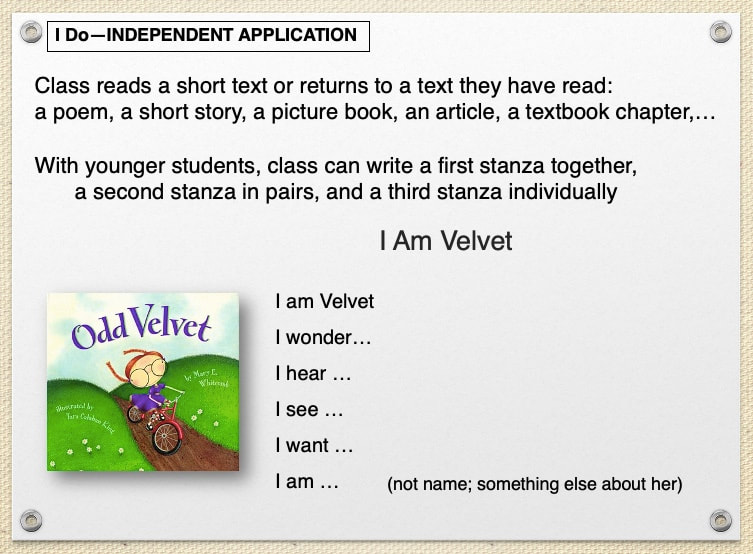

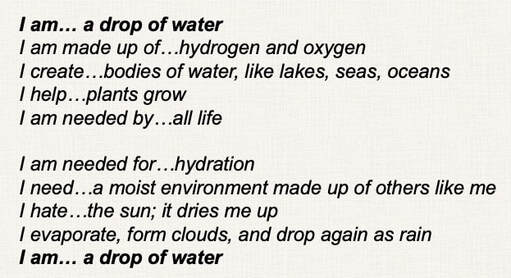

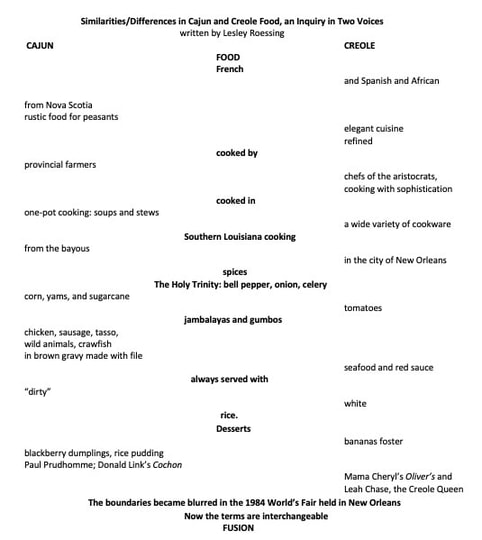

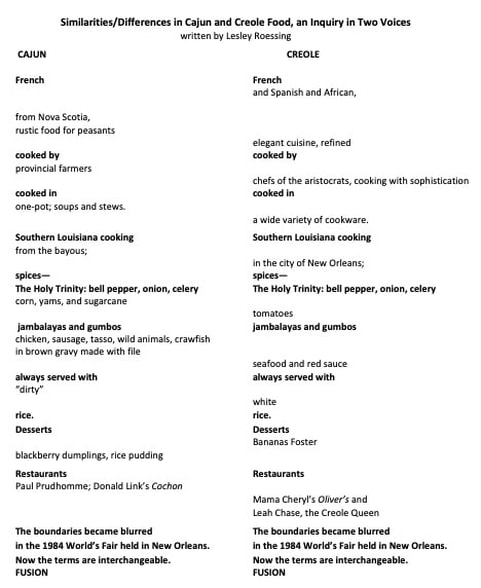

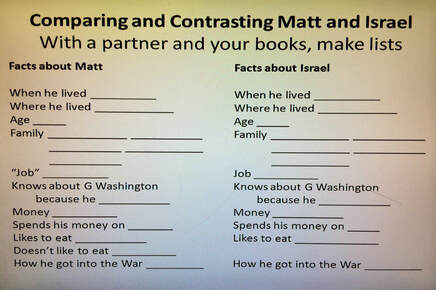

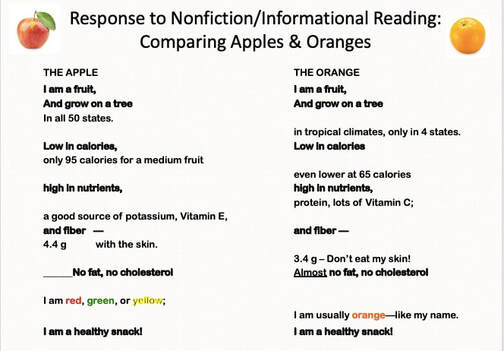

3. I AM POETRY In “I Am” poetry, readers write from the perspective of something they have read in a text or textbook. They could be writing from the perspective of a character in a story or poem; a person from a memoir or biography; a scientist or a scientific theory, element, or concept in science class; a person, event, or place in history; a mathematical concept or principle; or a disease, condition, or issue in health. The “I Am” poem follows a format that requires readers to read and analyze how the character, person, item, or event would view its world and its place in the world, returning to the text multiple times to apply what they have learned. This writing also causes readers to synthesize new material with information they already know or new information they may research to create their poem. In the case of items, events, or even places, particularly in social studies, science, math, and health classes, the writer would employ personification (Roessing, “After-Reading Response: I AM Poetry for Synthesizing Text” AMLE Magazine). Writing I Am poetry addresses the reading strategy of inferring. The typical format for an I AM poem is pictured below, but I always advise students that they can substitute their own verbs. This is a Gradual Release of Responsibility lesson that I taught in 2nd-4th grade classes: And here is a student example from a Science class (The Write to Read): More examples from middle grade students are included in the AMLE Magazine article linked above. 4. POETRY IN TWO VOICES Comparing and contrasting based on text read is crucial for deeper understanding, and readers need scaffolding to determine important information and organize it. One way of doing so is by writing Poetry in Two Voices. Students can compare two texts or compare elements, such as characters, settings, events, or ideas within a text or they can compare elements within a text to themselves or the world at large. As in all these reformulations, readers are going “back to the book” at a deeper level and interacting with the text. In writing Poetry in Two Voices, details that the two entities have in common are written and read together; differences are written on separate lines, the writer deciding which is to be read first. Hearing two students read two-voice poems aloud is very powerful. The poems can be written in the form of a Venn diagram (first example) or in two columns with the similarities directly across from each other and the differences on different lines (second example). This was a poem I wrote after using a variety of sources to determine the difference in Cajun and Creole cooking while attending a teacher workshp in New Orleans. For students of a 4th grade social studies class reading George Washington’s Socks, I helped them brainstorm and gather ideas from the novel with this chart. I reflected the chart on the white board as students helped me brainstorm and add "categories" before they went through the text to write their poems. This is a Teacher Model for for a Poem in Two Voices in response to nonfiction texts. After presenting students read an article on kiwi fruits and added a third "voice." ' In “After Reading Response: Poetry in Two Voices to Compare and Contrast" (Roessing, AMLE Magazine), I included examples from a 7th grade English-Language Arts class in which a reader compared/contrasted the two characters in Langston’s Hughes’ short story “Thank You, Ma’am”; 6th grade Social Studies where two students worked together to compare and contrast Cinderella figures from folktales of two cultures; and 8th grade Honors Science in which two students wrote a poem in the voices of convergent and divergent plate boundaries. 5. A-B-C BOOKS OF FACTS Students individually of in groups create a book of facts either A-Z or spelling out the topic or person about which they read. These examples were written by a 3rd grade student reading and reflecting on Frederick Douglass with the letters of his name and a secondary student's A-Z response to books and research reading about the rainforest. PRESENTATIONS Another way to guide readers back to the text is for readers to prepare presentations for their classmates. There are a variety of presentations; many of these are described in The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension and, for Book Clubs, in Talking Texts: A Teacher’s Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum. Some presentations ideas are

The primary objective of Before, During, and After-Reading Response is to promote reader interaction with text for better comprehension and deeper understanding. Reader response is a tool for thinking and for unlocking the text.

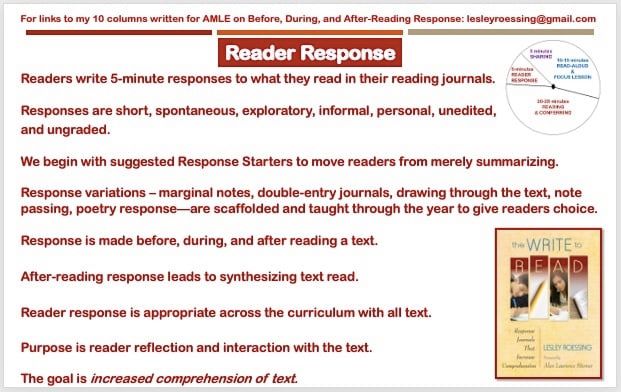

Dear Mom, This year we have learned a whole new way of responding by journal entries. It really helps you think about what you’re reading, and since it is all on paper you can always go back and think about things you have changed about your reading in the past. What we usually write about is like a little bit of a summary, not too much though, then we talk about some of the strategies we used and what we were thinking while reading. I like it a lot because I get to see what I thought before I read the book and then after. - Hollie (from The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension) Day after day students sit in front of us, reading books—whole-class, shared texts; book-club novels; or independent, self-selected books. We look at these readers and wonder, “What are they thinking?” We can listen in on book clubs, running from meeting to meeting, evaluating those we catch in the act of sharing. And we can move around the reading workshop, conferring with students one-on-one, sometimes disrupting their reading while trying not to disturb those nearby. But how can we tell if students are interacting with the text and thinking about what they are reading and how can we help them to comprehend better and to read more critically? Teachers need to know if readers comprehend, what they comprehend, and how they comprehend. And we need a way to assess reading to formulate our lessons to grow them as readers. Amidst all the controversy of whether students should have to write anything while, or after, they are reading, I say that it depends on what teachers are having readers write and how they are requiring them to write it. And WHY they are requiring students to write. If readers are required to answer questions on the text; write in formal, edited paragraphs; keep a log (and get parent signatures); or write book reports; I agree that these activities will not increase comprehension and will inhibit the pleasure of reading. However, in my experience and research, I have found Reader Response to be absolutely invaluable for letting teachers see if, what, and how students are reading. Most importantly, Reader Response shows us how a student has read and thought about text, and response allows us to help our students read authentically, interacting with text. Response demonstrates how readers make meaning from what they read and whether they are truly engaged in what they are reading. Students responses serve as formative assessment, informing teachers which lessons—reading strategies and/or literary elements—they need to teach (or re-teach) and to whom: whole-class, small group, or individual reader during Reading Workshop conferences. According to the 2010 Carnegie report "Writing to Read" (and my classroom "research"), students writing about what they read is the most effective strategy to increases comprehension. “The consensus of the research as well as my experience is that the more students read, the better they read. However, I have found that to a great extent that conclusion depends on the definition of “better.” I agree that students will read more fluently, but first we have to examine what “reading” is. Many students think they are reading because they can understand the words and then summarize the plot or, in the case of nonfiction, find the facts. But teachers need to recognize if their students really comprehend what they are reading. If not, teachers must distinguish where the breakdown occurs and then identify what they can do to help individual students improve comprehension and assist in taking comprehension to a more profound level. Many students do not automatically advance to more challenging material or push themselves to think about their reading on different levels. Students can read without awareness—unconscious of literary devices, inattentive to writer’s craft, lacking insight of comprehension skills they are using—in other words, without interacting with the text.” (The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension) WHAT IS READER RESPONSE? Reader Response, also known as Writing to Learn, is short writings, jottings, or journalings of the readers thoughts and reflections while reading any text—novels, short stories or folk tales, poems, informational articles, textbook chapters, even math word problems. Authentic reading is interactive; in order for students to learn, understand, and remember information, they must act on it. Journaling is a way of manipulating, exploring, challenging, and storing information. Journaling should be

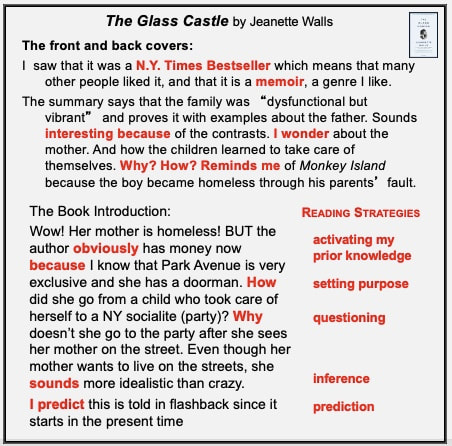

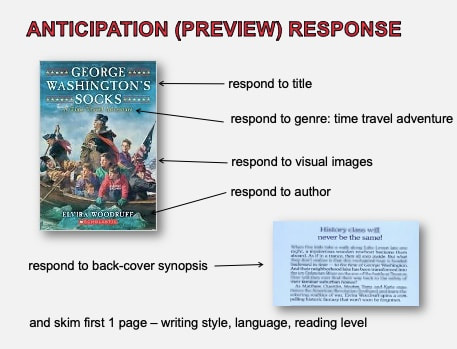

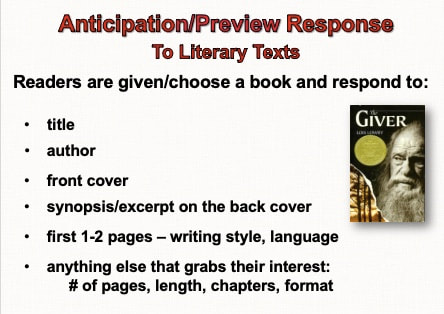

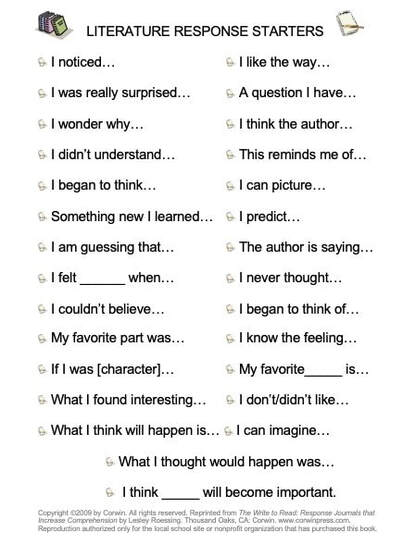

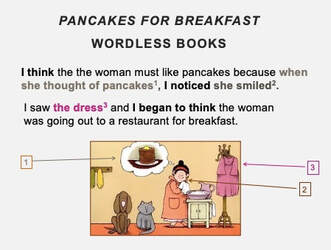

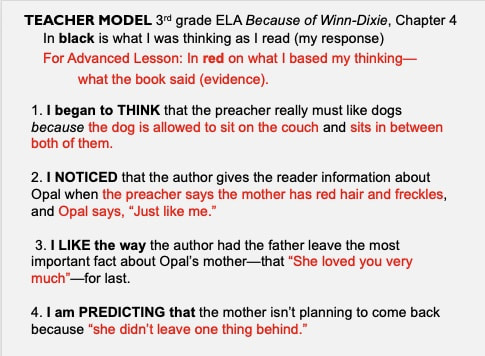

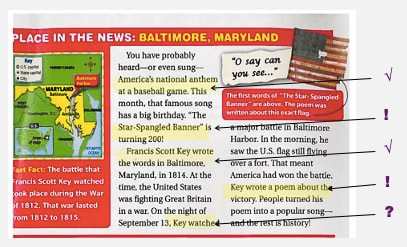

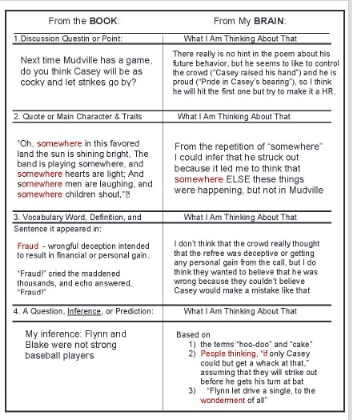

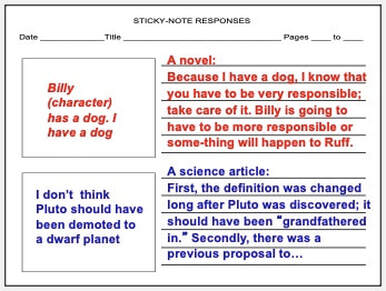

To be effective, Reader Response must be taught, modeled, and guided and eventually allow for reader choice. The purpose is to encourage readers to interact with text; the goal is increased comprehension. However, response should always be secondary to reading for pleasure and meaning and, therefore, the reason response is short and informal. Every reader’s 5-minute response will look different; some will be longer and deeper, demonstrating critical thinking; some will be shorter and show less more surface thinking (which will improve during the year). This is differentiation. I had some readers who wrote for much longer than 5 minutes because they wanted to share. They said they felt like they were chatting with me about their text. When some of my more proficient readers and writers wrote just a few lines, I responded, “This is not your 5-minute response. I will expect a bit more next time.” When more reluctant readers and writers wrote more than they had, I celebrated through a note in the journals. Courtney wrote about how her responding changed during the semester: I’m responding to what I read about the same amount but a lot deeper. My focus shifted from just taking the reading literally to thinking and analyzing it or making new comparisons to the world. Before, all my comparisons were to myself or other books, and now they relate to the outside world. A lot of my previous journal entries were questions and I didn’t respond to what I thought the answers were (which I do now). My recent journal entries have a lot more content than my older ones. Reader response journals also prepare readers for text discussion. In whole-class or small-group discussions, students can refer to their journals for points they can make. More reticent students can even read one of their responses as their contribution to a discussion. Reader Response is a timely topic, both because comprehension and adolescent literacy are crucial areas of concern and because response training leads to proficient performance on high-stakes reading and writing tests as students are trained to write critically and to respond to all types of literature, and texts fiction and nonfiction. I taught my student three types of response: BEFORE-READING RESPONSE, DURING-READING RESPONSE and AFTER-READING RESPONSE, all of which are essential to the process of interacting with, and learning from, text. BEFORE-READING RESPONSE Before-Reading Response (or Preview Response or, as I refer to it in The Write to Read, Anticipation Response) is crucial to activate prior knowledge, helping readers to make sense of new information and construct meaning from text. Also, Before-Reading Response prompts readers to set personal purposes for reading. Activating prior knowledge and setting a purpose for reading are considered two of the most valuable reading strategies. Another advantage is that Preview Response turns reading into inquiry: What do I know about this? What do I want to know? A Preview Response is a reflection based on previewing or skimming an upcoming text, focusing on text features, such as titles, authors, pictures, illustrations, subtitles, graphics—features that differ based on the text being previewed. Response can be oral or, more effectively, written. In a Preview Response readers make inferences about, and predictions of, what will be read, and such response can be effectively implemented in all disciplines with all texts. Below is (1) a Teacher Model based on the covers and Introduction of The Glass Castle, (2) Guided Practice with 4th graders getting ready to read George Washington's Sock, and (3) 8th graders preparing to read The Giver. >Read more about Preview Response, with examples from students reading science, social studies, and math texts, in “Before-Reading Preview Response,” one of my columns for AMLE Magazine and in The Write to Read: Response Journal That Increase Comprehension on which this blog is based. , DURING-READING RESPONSE During-Reading Response is response students write while they are reading a text. Effective written responses should be meaningful and compel readers to explore, question, and challenge text and make connections and inferences so they can construct meaning and learn from text. During reading response is short, personal, informal, exploratory, unedited, and ungraded. There are many formats for During-Reading Response. I scaffolded and taught each type, many of which I created for my students, through the first half of the year, based on analyzing what proficient readers do—maybe not on paper, but in their heads and in conversations with other readers. In this way, readers added to their “toolbelts” and towards the goal of deciding how best to respond in their journals based on their preferences and most appropriate for the texts they were reading. An academic team or self-contained teachers can start with one response strategy in ELA, then add social studies, then science, and then math, and health and art, so that students are responding to texts (including visual texts) across the curriculum. I worked with one school where, when I returned to train in After-Reading Response, the music teacher was having students respond to music and the football coach shared that he had players responding to diagrams of plays! I have found that the greatest problem with students’ responses at the beginning of the year is that readers, even my college students, tend to write summaries instead of reflections. After we discuss (respond) to a text orally, I hand out a list of Response Starters to add to their Reading Journals, and we examine them. We discuss some of the stems we heard in our class discussion, and students are encouraged to suggest others to add to the list. Students began with trying out some of the Response Starters in their responses, moving to the point where they just might choose one to begin their response which moves them away from the habit of summarizing into the response mode. Even our youngest students can read and respond to a wordless text. Visual readers point to the image that they are responding to, orally or in writing. (1) is an example of response to pictures and a Teacher Model based on a chapter of Winn-Dixie which the students had already read. > Read more about Response Starters, with examples from students reading a science article and a math word problem in “Reader Response In All Disciplines,” one of my columns for AMLE Magazine and in other content areas in The Write to Read: Response Journal That Increase Comprehension, the book on which the AMLE Magazine columns and this blog is based. ----------- There are a variety of ways readers can respond during their reading of the texts of all types, all of which help increase text engagement and comprehension. Some I adapted, and some I created, andI scaffolded them—introducing and moving on when students had successfully demonstrated the idea because the point was to give readers the options so they could choose the option that best fitted, which in some cases was a hybrid of strategies. MARGINAL NOTES Especially effective with informational text (and with reluctant writers) was a response that I referred to as Marginal Notes for which the teacher, or the class together, assigns logos—simple, easy-to-draw, and easy to remember symbols—to statement readers can make about text: \It is most effective to introduce readers to the concept of marginal notes by introducing and employing three logos with a text, such as an article, and when the students are familiar with those three, adding two more and then two more, until they are employing all logos as marginal notes to show their thinking. Students read an article marking a “note” or logo in the margin. Teachers can require a certain number spread out over the article, differentiating for different readers. Besides causing readers to interact with the text as teachers can observe if they walk around during the reading-marginal noting here are many options of what readers can do after they mark a text. Below is my Teacher Model for a lesson on Marginal Notes. >In my column on “Marginal Notes” for AMLE Magazine and in The Write to Read, there are a variety of student examples. DOUBLE-ENTRY JOURNALS Many teachers are familiar with double-entry journals or dialectical journal journals. I find them especially effective because teachers can see, and students can remember, to what text they responded, thereby making visible the reader's thought processes. The forms I designed included two columns: the left-hand column, labeled “From the Book,” presents the text evidence; the right-hand column, “From my Brain,” shows the reader’s thinking. The teacher can first model from a chapter or text the students have already read, such as my example from Mr. Popper’s Penguins with an elementary class or the poem "Casey at the Bat" with a secondary class. >In my column on “Double-Entry Journals” for AMLE Magazine are student examples from ELA, social studies, science, and math classes. The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension includes 6 different types of double-entry journals, depending on the Reading Focus Lessons being taught and a plain form for content area classes, and Talking Texts: A Teachers' Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum includes double-entry journals for Book Club readings and meetings. STICKY-NOTE RESPONSES Many teachers ask students to post sticky notes in their chapters as they read. The problem I found was that small Sticky Notes lead to small (shallow) thinking. This was my solution: After reading and sticking Sticky Notes in book, in class students can choose 3-4 Sticky Notes to place in the squares of a Sticky-Note Double-Entry journal (pictured) on left side; on right side, they further respond to their original response, thereby delving deeper and developing their thinking. In a way, this could be turned into a “triple-entry journal” if a column was inserted on the left for the text responded to. VISUAL RESPONSE or DRAWING THROUGH THE TEXT Responses do not always need to be in words. Proficient readers visualize as they read a text. They use the words from the text, in combination with background knowledge and prior experiences, connections from their lives and other texts, and inferences made, to construct mental images. When readers create images in their minds that reflect or represent the ideas in the text, they comprehend text at deeper levels and they retain more information and understanding. The most effective way to teach students to visualize is to teach readers to draw images as they read a text as a during-reading response strategy. It is important that readers include the words or phrases to which they are responding. I would even suggest a double-entry journal with lines for the text on the left side and blank spaces for drawings on the right side. The advantages of drawing as response:

>My Reader Response column "Ideas for Helping Readers Visualize Text to Promote Comprehension at Deeper Levels" includes teacher directions for this response activity. CONCLUSION As one can probably tell, I am passionate about employing Reader Response. Year after year, I observed my reluctant readers become real, even ravenous, readers, increasing their comprehension and raising reading levels. At the same time, I noted my proficient readers reading more deeply and critically. All readers had more to contribute to class and small-group literary discussions. Since my readers read more than they ever had before, it was obvious that reponse journaling did not curtail their new found-love of reading. A few words from my students: Stopping every 25 minutes to write allows me to reflect on the character’s actions, make connections, and understand why the author writes the way he does. I have also been exploring different genres of literature during my reading journals this year. I have read sports, adventure, mystery, historical fiction, short story collections, and comedy. Not only have reading journals helped me in just my reading comprehension, but it also has improved my writing skills. Analyzing the author’s style influences my own methods of writing. -John (from The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension) and I have to say I’ve evolved as a reader. I think it’s because reflecting on reading really got me thinking about what I read. Now it was more than just words in a book. It was like entering a different world every time I picked up a book. -Carly (from The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension) Another advantage for me and for my readers is that I never felt the need to quiz or test their reading or comprehension of texts. The evidence was in their journals. See PART 2 AFTER-READING RESPONSE

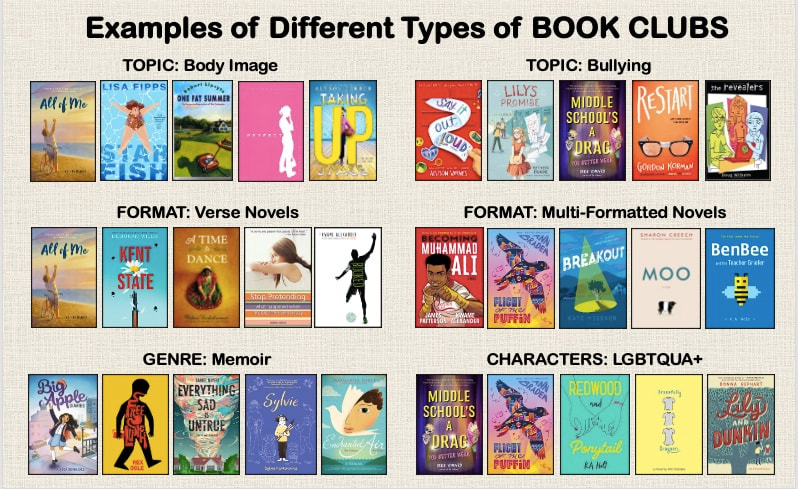

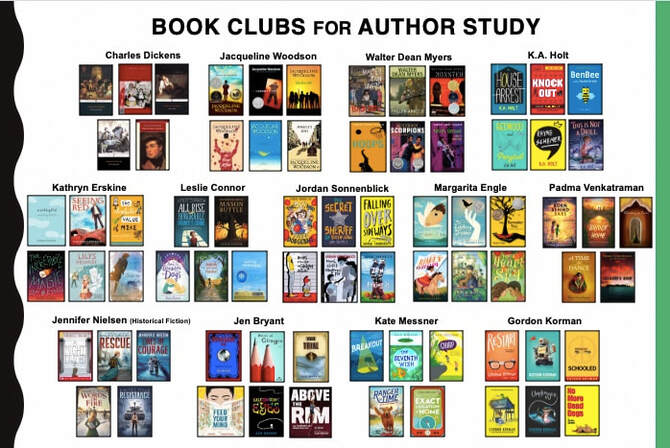

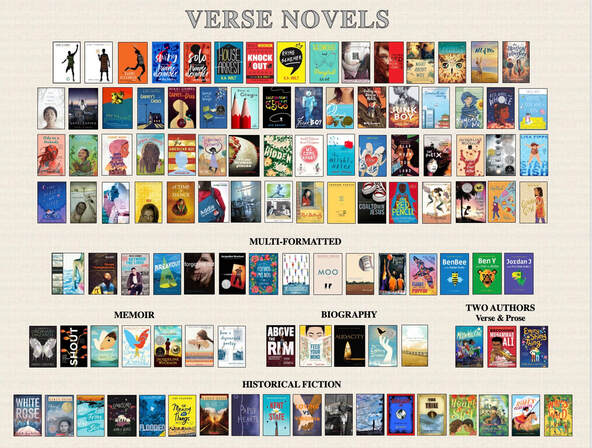

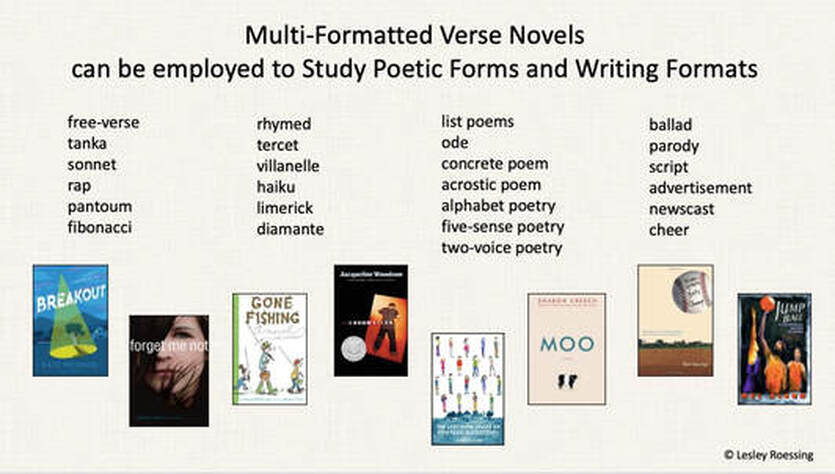

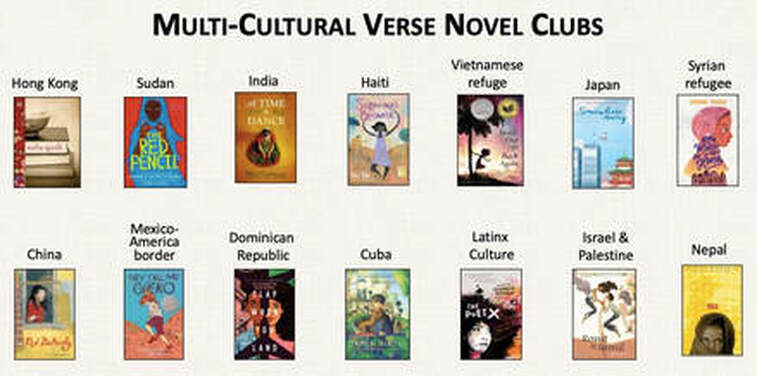

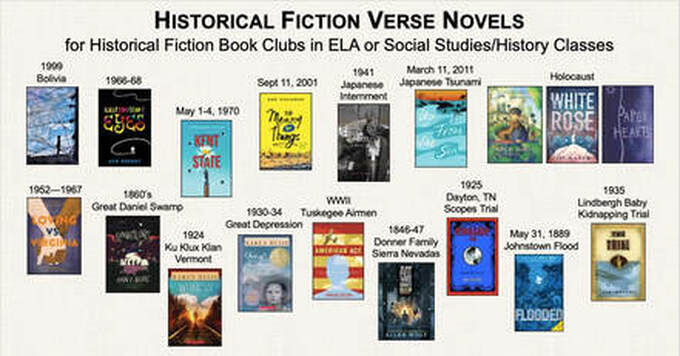

Text Clubs have many advantages which I have written about in the introduction to the Book Reviews section. Besides Nonfiction or Informational Book Clubs, Short Story Clubs, Poetry Clubs, Folklore Clubs, Article Clubs, and even Textbook Clubs, all of which are described in Talking Texts: A Teacher’s Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum, Novel Book Clubs are the most familiar type of Book Club and can be organized in a variety of ways. These are some suggestions for choosing books for Book Club reading. AUTHOR STUDY BOOK CLUBS As I share in Talking Text, my first book club was a matter of necessity. It was 1989 and, other than my mother’s monthly book club, I had not heard of the practice used in the classroom but in my first job which was that of a 11-month permanent substitute, my curriculum guide for Senior Honors stated that I was to teach a Dickens novel. Looking around the classroom I found about 5 copies of one novel. Going to the library, I found a few copies of other Dickens novels. Searching, borrowing, and purchasing, I came up with 5-6 copies of five novels written by Charles Dickens. And so my first Book Club adventure began. I taught background on the author and his times, the students each chose a novel to read, and Author Study Book Clubs were formed. After each group read and discussed their novel, they prepared a creative presentation to the class. In that way, students read one novel but learned about five. Author Study Book Clubs can be structured in a variety of ways. Then teacher can give background on the author or students can individually or later, in book clubs, study different biographical facets of the author, including time period, geography, cultural background, other publications, etc. which they will share with their clubs and later with the class. The class can read a whole-class text written by the author, ideally a short story. Or the Book Clubs can choose books based on teacher book talks and/or looking at the covers and skimming a few pages of each book. [See Talking Texts for more in-depth information on forming book clubs.] As with the Dickens Book Clubs, each book club read and holds 4-5 meetings to discuss their reading and then prepare a presentation to the class in which they include their observations on not only the content by the author’s craft. Books clubs can compare and contrast the author’s writings as a class or in Inter-Book Clubs where one member of each book club meets in a group to compare and contrast and report their findings. How to choose an author? The most effective is to choose authors who have published at least 5 texts. Ideally the author would have published a short story that the class and read together to begin and build on, but that is rarely the case. I find that it is effective to find authors who write in different genres, such as Walter Dean Myers who has published memoir, historical fiction, realistic fiction, “street life” fiction, sports fiction, and romance, as well as collections of short stories (which are good for slower, more emergent readers who may not be able to finish an entire novel in the same time period as their peers. Also it is best to choose an author who has written in a variety of reading levels. More rare but effective would be to choose an author who has written in a variety of formats, such as prose, verse, graphic, and multi-formatted, such as Laurie Halse Anderson who wrote the graphic novel Wonder Woman: Tempest Tossed but her novel Speak was re-written as in graphic form. Or an author such as Jennifer Nielsen who has written historical novels taking place in different time periods. If you cannot read the titles, look up the author on Goodreads for titles and synopses.  FORMAT BOOK CLUBS In Format Book Clubs book club members read books written in the same format, such as verse novels, graphic novels, epistolary novels (or now, novels written through letters, emails, and/or texts) or, gaining in popularity, multi-formatted novels. Format Book Clubs allow teachers to teach focus lessons on the format. VERSE NOVEL BOOK CLUBS For example most novels-in-verse are written in free verse, so the teacher can teach that format but also poetic devices such as figurative language of all types. I think the power of free verse is in the line break choices. I always described line breaks as an eye-pause, when reading it is short than a comma but your eye is forced to pause and notice a particular word or phrase. Discussion can be held on why the author chose to break on that word. Stanza length, which usually varies, inspires other reflective conversations. Verse novels are written in most genres, such as historical fiction, memoir, biography, humor, realistic fiction. Some authors only write in verse format; others write in a range of formats. Such novels are written by culturally-diverse authors on diverse topics, featuring diverse characters and settings. Many verse novels are written in a variety of poetic forms which lead to lessons or study of the different types of poetic formats. Leslea Newman’s October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard is written as 68 poems about Matthew Shepard and his murder. A range of emotions is shared through a variety of poetic styles: free verse, haiku, pantoum, concrete, rhymed, list, alphabet, villanelle, acrostic, and poems modeled after the poetry of other poets, thereby, not only introducing to the “what” of those formats but the “why.” But most importantly, novel-in-verse is a text format which engages readers for divergent reasons:

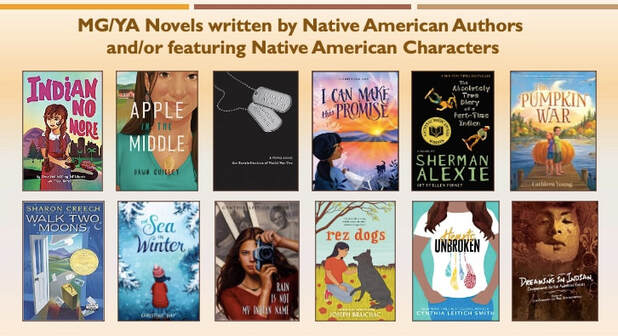

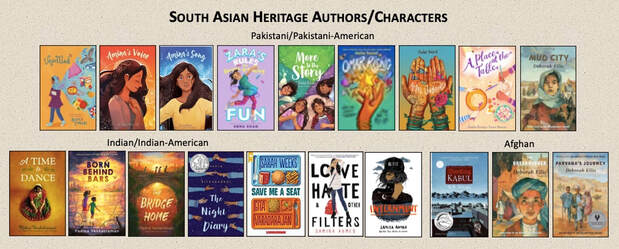

GRAPHIC BOOK CLUBS It is important that teachers teach visual literacy. Citizens of the world are bombarded with images daily—in the news, as advertising, body language and facial expressions. Reading and studying graphic text allow readers to learn to read visual clues. The advantages of holding Graphic Novel Clubs are that, besides engaging many reluctant readers, artistic students will learn to appreciate the congruity of art and text and the graphics make it possible for our ELL readers to interpret a text. I have not read many graphic novels but teachers/librarians can facilitate Graphic Book Clubs with an assortment of graphic texts as shown or hold Graphic Historical Fiction Book Clubs or Graphic Memoir Book Clubs. CULTURAL BOOK CLUBS Besides advocating for diverse cultures to be represented in Book Club choices, Cultural Book Clubs can be developed around the cultures of the author, characters, or setting. Pictured are some examples. It is vital that readers see their cultures reflecting in stories they read as well as using story as passage into other cultures. This type of Book Club can lead to research into cultures which Clubs will then present to their peers who may be reading novels set in, or featuring characters representing, other cultures.  GENRE BOOK CLUBS Genre Book Clubs can facilitate students exploring a genre and to see the variety of topics that can be covered by a genre. When planning a genre study, it is effective to include diverse authors and/or characters and formats—not only prose, but verse, graphic, and/or multi-formatted. Genre Book Clubs can be created around Historical Fiction, Sports Fiction, Memoir, Mystery, Science Fiction, Fantasy, Dystopian, Magical Realism, etc. Historical Fiction novels can be read and discussed in Social Studies/History classes or in ELA/English classes or as part of interdisciplinary units in both. One suggestion is that in a Social Studies class, each Historical Fiction Book Club reads a novel from a different time or place that will be covered in the curriculum that year, and, when that time/place is being covered in class, the Book Club makes their presentation to the class or all Book Clubs present at the end of the year as a review. STEM BOOK CLUBS Not really considered a genre are Disciplinary Book Clubs—math, social studies, science, health, art, music. The novels pictured include science and math connections and can be read in those two classes or in ELA or English classes with collaborative interdisciplinary lessons. Some of them, such as Fever 1793, can be employed across the curriculum. THEMATIC BOOK CLUBS

The most obvious organization for Book Clubs is Thematic or Topic Book Clubs and most of what I share in Facebook posts and in the Book Reviews sub-sections of this site are Thematic Book Clubs, such as those posted under the Book Review section: Teen Justice & Change Seekers and Surviving Loss. Other topics or themes around which I have planned Book Club reading are