- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

- Asian, Asian-American

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

|

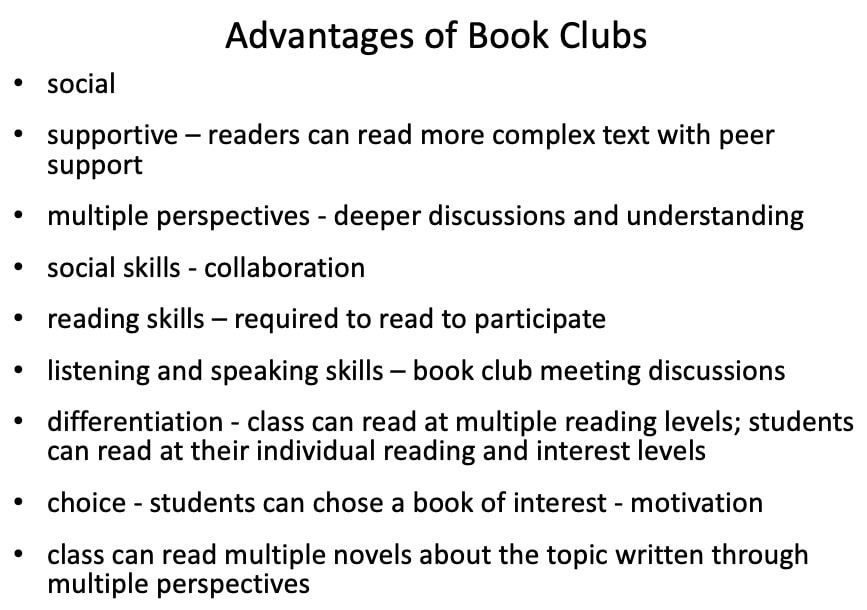

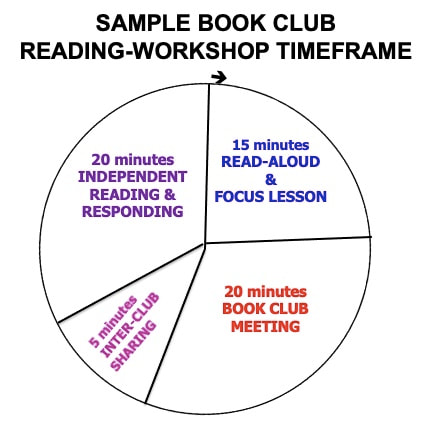

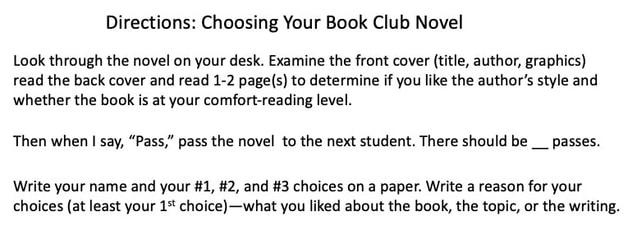

In a gradual-release-of-responsibility model of teaching reading, this would be about the time of the school year that teachers are moving from whole-class short stories (to teach or review reading strategies, literary elements, and author’s craft [see Reading Strategy #6]) and whole-class novel(s) [see Reading Strategy #9] to reading in BOOK CLUBS in the move toward independent, self-selected reading [see “Losing the Fear of Sharing Control”]. Of course Book Clubs can be held any time, and my students always clamored for "one more Book Club" in the midst of independent reading. I have facilitated BOOK CLUBS in Grade 3 though university classes in English-Language Arts and content area classes. I have written extensively about the benefits of reading in BOOK CLUBS. And I have written about holding TEXT CLUBS to read poetry, short stories, folktales, nonfiction books, articles, and textbook chapters in collaborative small groups. For strategies, lessons, assessments, models, and reproducible forms, see TALKING TEXTS: A Teacher’s Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum. These are my 5 basic steps for facilitating any type of BOOK CLUB (or TEXT CLUB). 1. SETTING UP BOOK CLUBS

2. TEACHING SOCIAL/DISCUSSION SKILLS

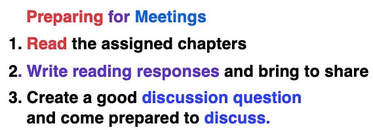

3. TEACHING BOOK CLUB PROCEDURES

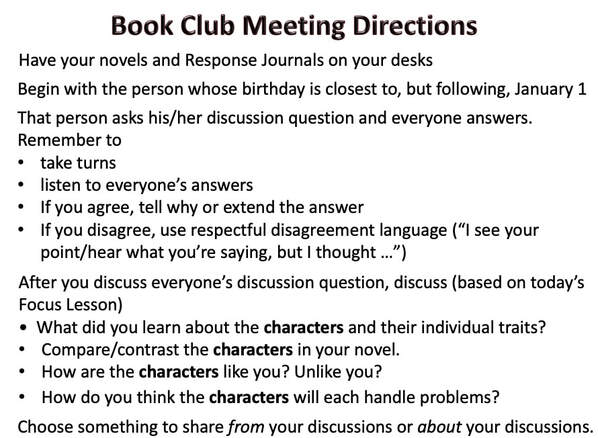

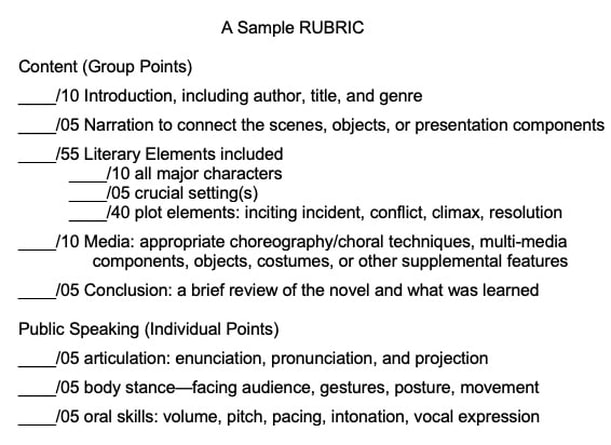

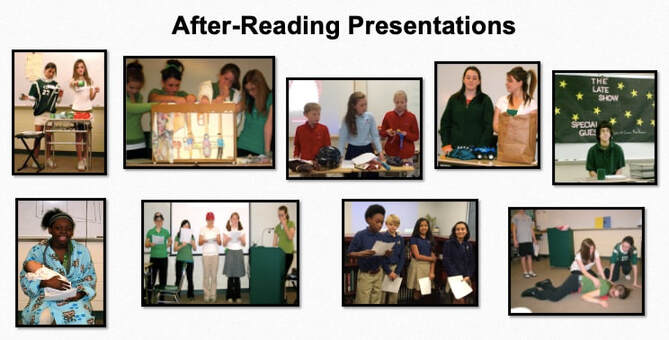

4. FACILITATING BOOK CLUB MEETINGS This is one class sample directions; the day's Focus Lesson centered on character traits) 5. ASSESSMENT a. READING: I assessed reading based on their Reader Response journals which they used for their discussions (see TALKING TEXTS and THE WRITE TO READ for my lessons and reproducible forms). b. MEETINGS: I assessed meetings by observations and by student self-assessments c. PRESENTATIONS: My GUIDELINES:

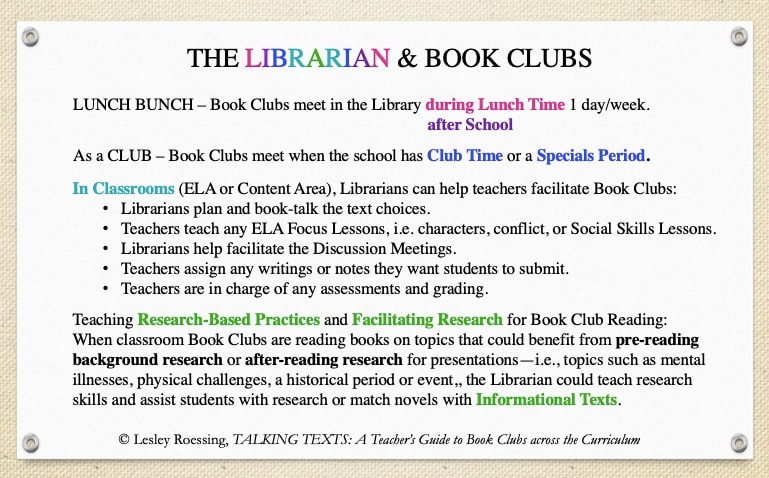

A percentage of the grade was based on the content of the group presentation and a percentage was based on individual speaking points. My typical BOOK CLUB Schedule, a sample: WEEK 1-- Monday: discuss Book Club expectations, Social Skills Focus Lesson, Book Talks and Book Passes Tuesday: Discussion Lesson (Strategy #10); distribute novels; Book Cubs meet to plan reading Wednesday: Creating Discussion Questions Lesson; Reading Time Thursday: Lesson on Book Club Procedures; Reading Time Friday: review Discussion or Social Skills Focus Lesson; Book Club Meeting #1 WEEK 2-- Monday: Literary Focus Lesson; Reading Time Tuesday: Literary Focus Lesson; Book Club Meeting #2 Wednesday: Literary Focus Lesson; Reading Time Thursday: Literary Focus Lesson; Reading Time Friday: Literary Focus Lesson; Book Club Meeting #3 WEEK 3-- Monday: Literary Focus Lesson; Reading Time Tuesday: Book Club Meeting #4 and Reading Time Wednesday: Literary Focus Lesson; Reading Time Thursday: Book Club Meeting #5 Friday: Lesson on Presentation Choices and Expectations; Public Speaking Lesson WEEK 4-- Monday and Tuesday: Book Clubs works on Presentations Wednesday; Class Presentations And strategies for LIBRARIANS who wish to start or work with BOOK CLUBS:  TALKING TEXTS: A Teacher's Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum includes classroom strategies, focus-lessons, and reproducible forms for facilitating, organizing, integrating, and assessing collaborative, small-group reading and teaching effective, supportive discussion techniques in Grade 3 through university classes—strategies that work for all types of text: novels and memoirs, short stories, informational texts and articles, poetry, folktales, and even textbooks in all content areas.

1 Comment

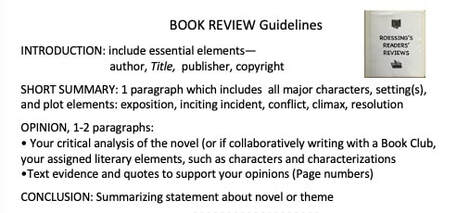

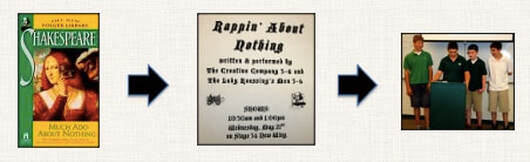

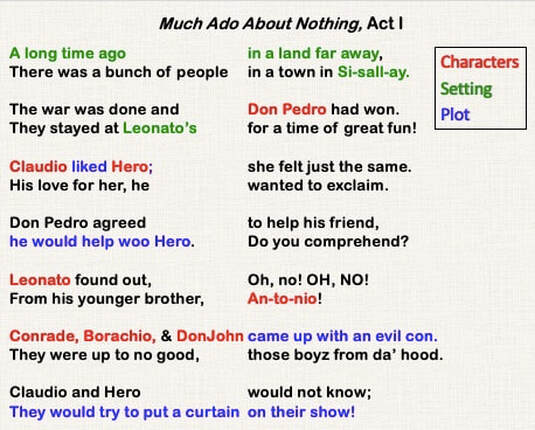

In my last blog, “The Importance of Reader Response,” I explain the value of READER RESPONSE and how response compels readers to interact with the text and makes visible for readers and their teachers the depth (and type) of text comprehension. I share strategies, activities, teacher models, and student examples for a variety of types of before and during-reading response. This blog will focus on the importance of AFTER-READING RESPONSE in all content areas. I cannot overstate the importance and advantages of returning to the text for synthesis. In synthesis, learners put together assorted parts to create a new whole, expanding understanding.I find that every time I reread a text, I create expanded, enhanced, and even more innovative interpretations, making the text more interesting and learning more from the text. Students notice this also and tell me, “I learned more this time” or “I never noticed that.” But how can we encourage students to return to the text—connecting the parts and responding to the writing as a whole—to construct or develop new ideas. When I finish a book, I may not build a project out of materials, but I do create a way to understand what I have read and the meaning of my understanding in my mind. As reflective reader I consider, or even discuss with others, my reading and the significance of what the author has said. I mull over the text, compare notes with other readers, and mentally contrast the text with other texts, either written by the same author or other writers. Sometimes I even compare the book with a movie based on the book. And that is what we need to do as teachers; we need to train our students to return to texts to question, interpret, compare, and analyze. If this process starts in school, it becomes internalized as students become better, highly- skilled readers. (The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension) I will describe different types of after-reading activities that not only promote synthesis of texts read, but share meaning created and, in the case of book club and individual reading, share texts with others. BOOK REVIEWS One of the most effective ways to teach readers to analyze books read (and teach critical thinking and argument writing) is through student Book Reviews which can be collected in a binder or on a website for access to other readers who are looking for reading ideas. I scaffolded Book Review writing through the year: Each marking period my readers were required to write a formal BOOK REVIEW (meeting multiple reading and argument writing standards). MARKING PERIOD 1: The CLASS first analyzed 3 published book reviews (NY Times, local paper, and from old copies of NCTE's Voices from the Middle) as mentor texts, deconstructing and noting elements that were included in ALL reviews and elements included in only SOME reviews. The "All" became required elements for their reviews; the "Some" were optional. I required a certain number of "optional" elements, differentiating for different students. The class then wrote a review together, critiquing our whole-class novel. Students brainstormed ideas together, collaborated on appropriate language, and then readers wrote individual reviews (or in pairs), using as much from the class discussions as they wished. MARKING PERIOD 2: Book Club members collaborated on a Book Review, critiquing their Book Club novel, each member analyzing a different literary element. MARKING PERIODS 3 and 4: Readers Individually choose 1 of their self-selected, independently-read texts to review. Reviews were typed and illustrated, usually with a picture of the cover, and housed in the Roessing Readers' Reviews binder which was divided by genre (as was our classroom library) for readers to peruse when looking for a next book to read. √These also could be uploaded to a class, teacher, or library computer as a digital binder. Pictured are my GUIDELINES FOR REVIEWS and a student Book Review from The Write to Read. See The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension and Talking Texts: A Teachers' Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum for more student samples and other ways readers shared their readings, individually and collaboratively. TEXT REFORMULATIONS I have found the best way to encourage students to return to the text is to ask them, as their after-reading response, to turn the text into a different format (reformulation), which can be applied to whole-class, small-group, or individual, self-selected readings. Each rereading of a text gives readers a greater and deeper understanding, making them better readers and increasing comprehension. Texts reformulations can be created and presented individually or in groups. And text reformulations can encourage the engagement of multiple intelligences: linguistic, mathematical, musical, spatial, kinesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and environmental. 1. RAPPING A TEXT Students read, performed, and discussed a Shakespearean play. After, they formed five groups; each group selected one act. The groups turned their acts into a rap, with the requirements to include all the major characters, settings, and important plot elements that occur in that act. They then performed their raps for the class utilizing public speaking techniques such as eye contact, enunciation, voice projection, and other choral reading techniques. After going back to the text to determine characters, setting(s), and analyzing the most important events in their acts, readers again went back and forth to the original text repeatedly, translating Shakespearean English to modern English to rap English and playing with rhyme. Students were so engaged with the activity and the product that they asked teachers in their other classes to release them to attend the performance of my other Humanities class, to listen to their raps. There are other students samples of reformulating texts into narrative poems, enhancing summarization skills, in The Write to Read. 2. FOUND POETRY Found poems take words, phrases, and details from existing texts and require readers to modify them, reorder them, and present them as poems, much as one does when creating a collage, resulting in learning and showing understanding in new ways. In the interest of true synthesis and showing one’s learning, I suggest that the found poetry employed in after-reading response writing include some of the reader/writer’s own thoughts about the text. Other decisions of form, such as where to break lines and spacing, are also left to the poet. (Roessing, “Using Found Poetry for Synthesizing Text,” AMLE Magazine) These are my directions:

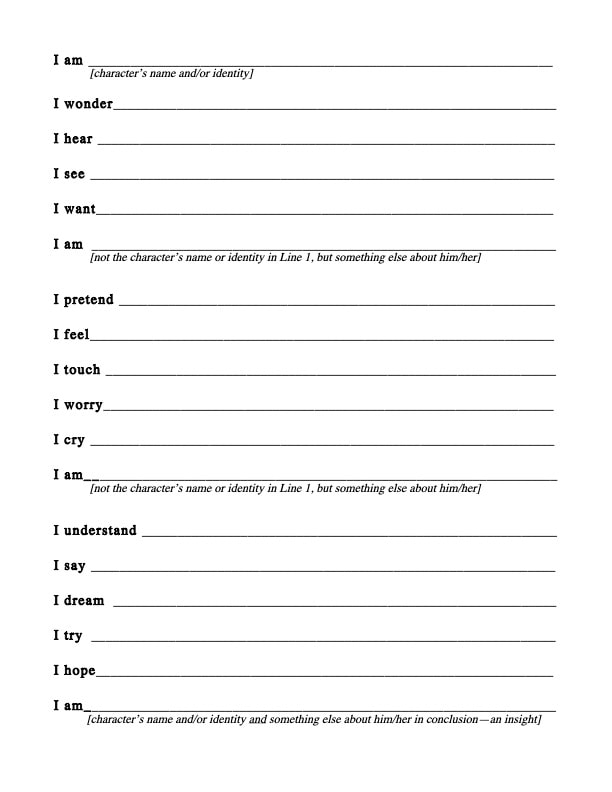

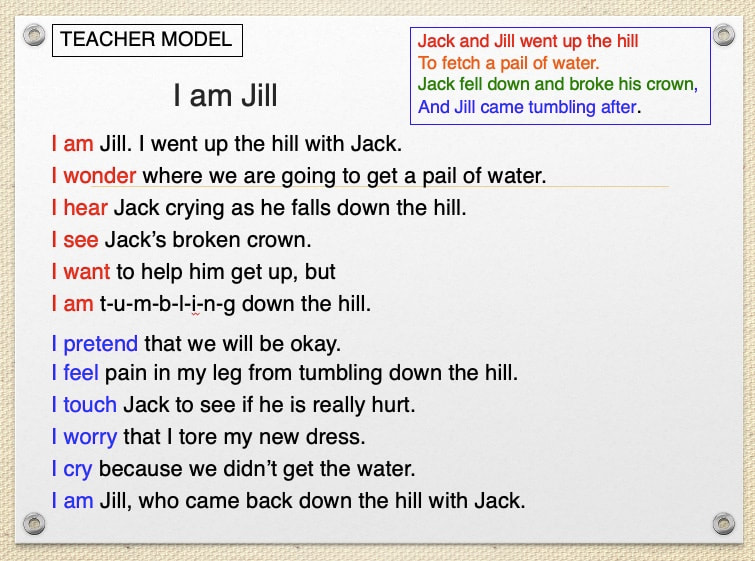

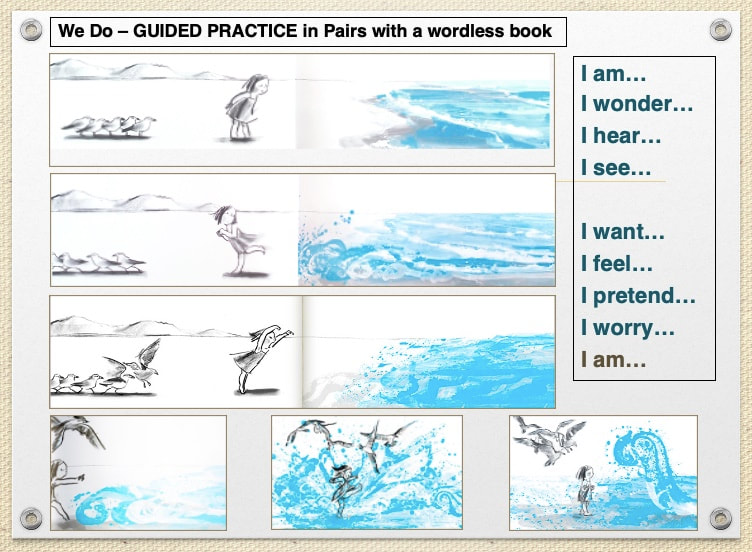

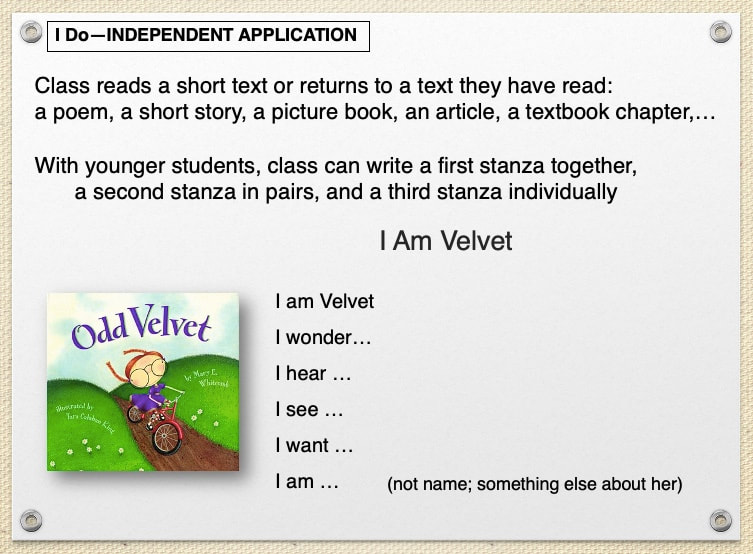

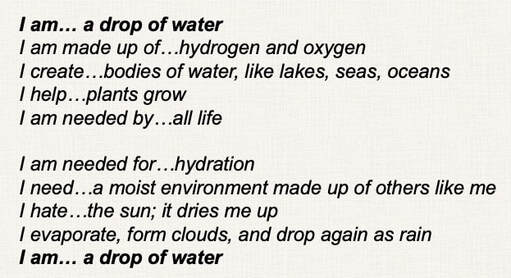

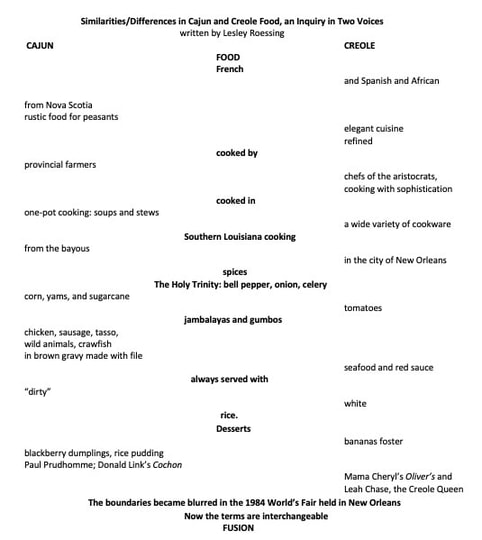

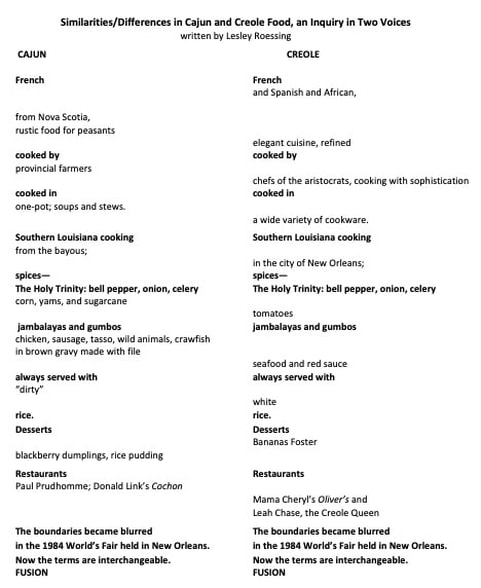

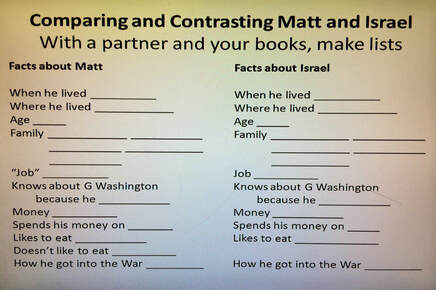

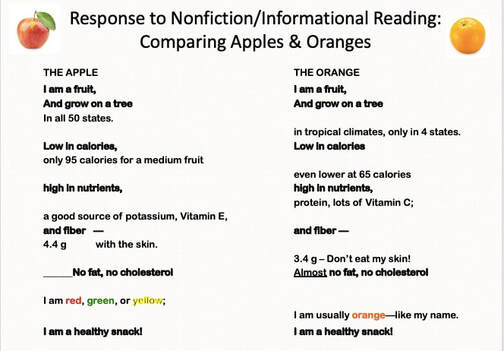

3. I AM POETRY In “I Am” poetry, readers write from the perspective of something they have read in a text or textbook. They could be writing from the perspective of a character in a story or poem; a person from a memoir or biography; a scientist or a scientific theory, element, or concept in science class; a person, event, or place in history; a mathematical concept or principle; or a disease, condition, or issue in health. The “I Am” poem follows a format that requires readers to read and analyze how the character, person, item, or event would view its world and its place in the world, returning to the text multiple times to apply what they have learned. This writing also causes readers to synthesize new material with information they already know or new information they may research to create their poem. In the case of items, events, or even places, particularly in social studies, science, math, and health classes, the writer would employ personification (Roessing, “After-Reading Response: I AM Poetry for Synthesizing Text” AMLE Magazine). Writing I Am poetry addresses the reading strategy of inferring. The typical format for an I AM poem is pictured below, but I always advise students that they can substitute their own verbs. This is a Gradual Release of Responsibility lesson that I taught in 2nd-4th grade classes: And here is a student example from a Science class (The Write to Read): More examples from middle grade students are included in the AMLE Magazine article linked above. 4. POETRY IN TWO VOICES Comparing and contrasting based on text read is crucial for deeper understanding, and readers need scaffolding to determine important information and organize it. One way of doing so is by writing Poetry in Two Voices. Students can compare two texts or compare elements, such as characters, settings, events, or ideas within a text or they can compare elements within a text to themselves or the world at large. As in all these reformulations, readers are going “back to the book” at a deeper level and interacting with the text. In writing Poetry in Two Voices, details that the two entities have in common are written and read together; differences are written on separate lines, the writer deciding which is to be read first. Hearing two students read two-voice poems aloud is very powerful. The poems can be written in the form of a Venn diagram (first example) or in two columns with the similarities directly across from each other and the differences on different lines (second example). This was a poem I wrote after using a variety of sources to determine the difference in Cajun and Creole cooking while attending a teacher workshp in New Orleans. For students of a 4th grade social studies class reading George Washington’s Socks, I helped them brainstorm and gather ideas from the novel with this chart. I reflected the chart on the white board as students helped me brainstorm and add "categories" before they went through the text to write their poems. This is a Teacher Model for for a Poem in Two Voices in response to nonfiction texts. After presenting students read an article on kiwi fruits and added a third "voice." ' In “After Reading Response: Poetry in Two Voices to Compare and Contrast" (Roessing, AMLE Magazine), I included examples from a 7th grade English-Language Arts class in which a reader compared/contrasted the two characters in Langston’s Hughes’ short story “Thank You, Ma’am”; 6th grade Social Studies where two students worked together to compare and contrast Cinderella figures from folktales of two cultures; and 8th grade Honors Science in which two students wrote a poem in the voices of convergent and divergent plate boundaries. 5. A-B-C BOOKS OF FACTS Students individually of in groups create a book of facts either A-Z or spelling out the topic or person about which they read. These examples were written by a 3rd grade student reading and reflecting on Frederick Douglass with the letters of his name and a secondary student's A-Z response to books and research reading about the rainforest. PRESENTATIONS Another way to guide readers back to the text is for readers to prepare presentations for their classmates. There are a variety of presentations; many of these are described in The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension and, for Book Clubs, in Talking Texts: A Teacher’s Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum. Some presentations ideas are

The primary objective of Before, During, and After-Reading Response is to promote reader interaction with text for better comprehension and deeper understanding. Reader response is a tool for thinking and for unlocking the text.

|

AuthorSee "About Lesley" Page Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed