- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

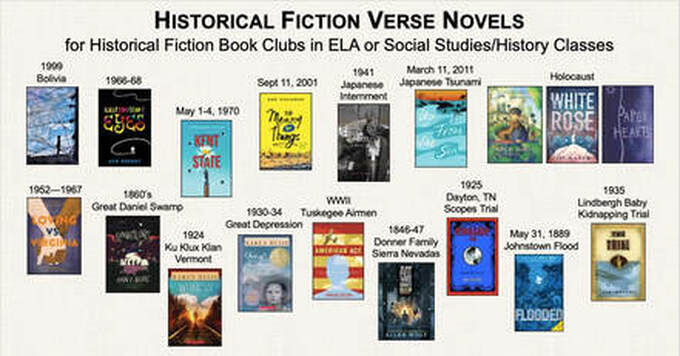

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

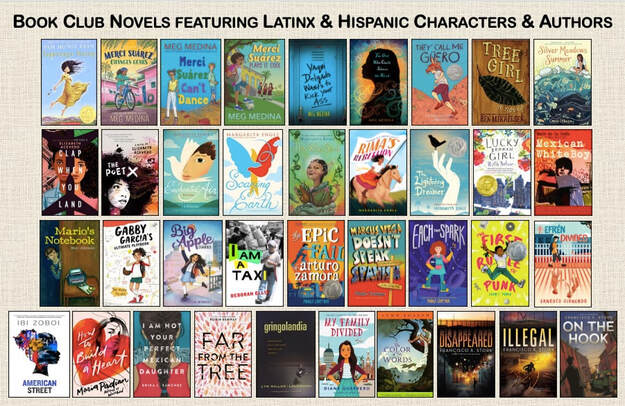

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

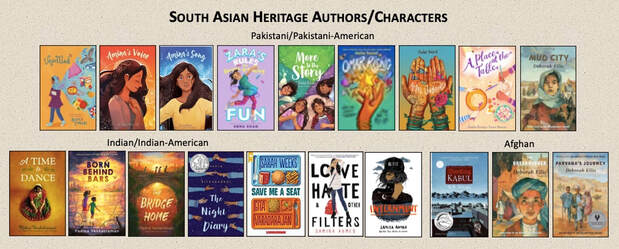

- Asian, Asian-American

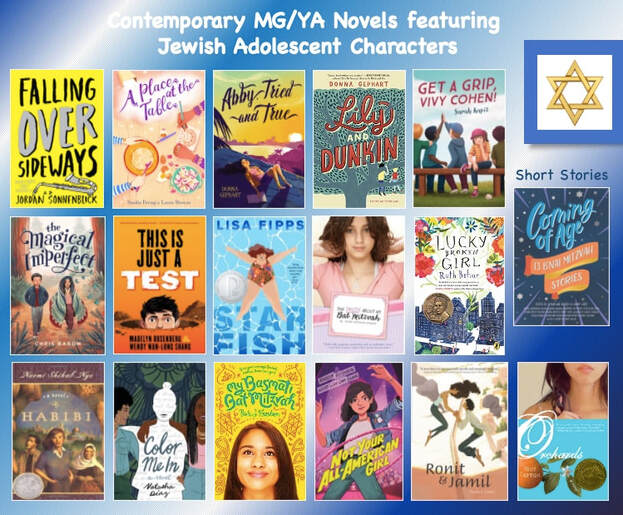

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

|

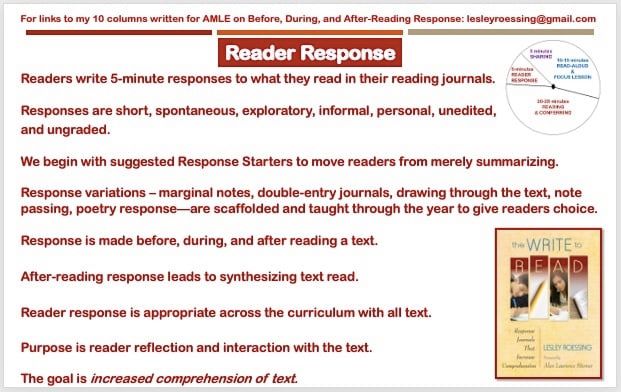

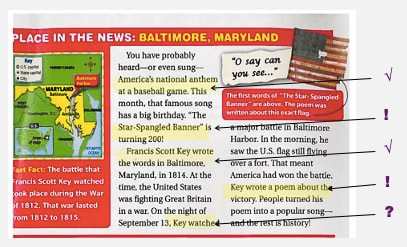

Dear Mom, This year we have learned a whole new way of responding by journal entries. It really helps you think about what you’re reading, and since it is all on paper you can always go back and think about things you have changed about your reading in the past. What we usually write about is like a little bit of a summary, not too much though, then we talk about some of the strategies we used and what we were thinking while reading. I like it a lot because I get to see what I thought before I read the book and then after. - Hollie (from The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension) Day after day students sit in front of us, reading books—whole-class, shared texts; book-club novels; or independent, self-selected books. We look at these readers and wonder, “What are they thinking?” We can listen in on book clubs, running from meeting to meeting, evaluating those we catch in the act of sharing. And we can move around the reading workshop, conferring with students one-on-one, sometimes disrupting their reading while trying not to disturb those nearby. But how can we tell if students are interacting with the text and thinking about what they are reading and how can we help them to comprehend better and to read more critically? Teachers need to know if readers comprehend, what they comprehend, and how they comprehend. And we need a way to assess reading to formulate our lessons to grow them as readers. Amidst all the controversy of whether students should have to write anything while, or after, they are reading, I say that it depends on what teachers are having readers write and how they are requiring them to write it. And WHY they are requiring students to write. If readers are required to answer questions on the text; write in formal, edited paragraphs; keep a log (and get parent signatures); or write book reports; I agree that these activities will not increase comprehension and will inhibit the pleasure of reading. However, in my experience and research, I have found Reader Response to be absolutely invaluable for letting teachers see if, what, and how students are reading. Most importantly, Reader Response shows us how a student has read and thought about text, and response allows us to help our students read authentically, interacting with text. Response demonstrates how readers make meaning from what they read and whether they are truly engaged in what they are reading. Students responses serve as formative assessment, informing teachers which lessons—reading strategies and/or literary elements—they need to teach (or re-teach) and to whom: whole-class, small group, or individual reader during Reading Workshop conferences. According to the 2010 Carnegie report "Writing to Read" (and my classroom "research"), students writing about what they read is the most effective strategy to increases comprehension. “The consensus of the research as well as my experience is that the more students read, the better they read. However, I have found that to a great extent that conclusion depends on the definition of “better.” I agree that students will read more fluently, but first we have to examine what “reading” is. Many students think they are reading because they can understand the words and then summarize the plot or, in the case of nonfiction, find the facts. But teachers need to recognize if their students really comprehend what they are reading. If not, teachers must distinguish where the breakdown occurs and then identify what they can do to help individual students improve comprehension and assist in taking comprehension to a more profound level. Many students do not automatically advance to more challenging material or push themselves to think about their reading on different levels. Students can read without awareness—unconscious of literary devices, inattentive to writer’s craft, lacking insight of comprehension skills they are using—in other words, without interacting with the text.” (The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension) WHAT IS READER RESPONSE? Reader Response, also known as Writing to Learn, is short writings, jottings, or journalings of the readers thoughts and reflections while reading any text—novels, short stories or folk tales, poems, informational articles, textbook chapters, even math word problems. Authentic reading is interactive; in order for students to learn, understand, and remember information, they must act on it. Journaling is a way of manipulating, exploring, challenging, and storing information. Journaling should be

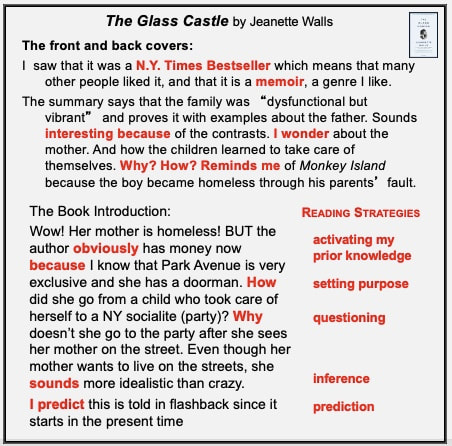

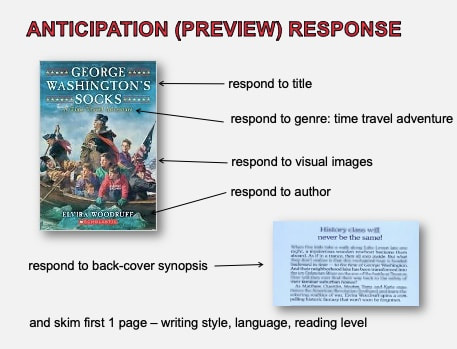

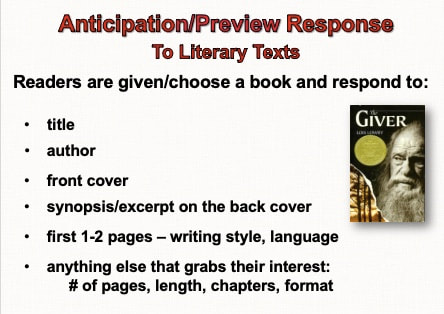

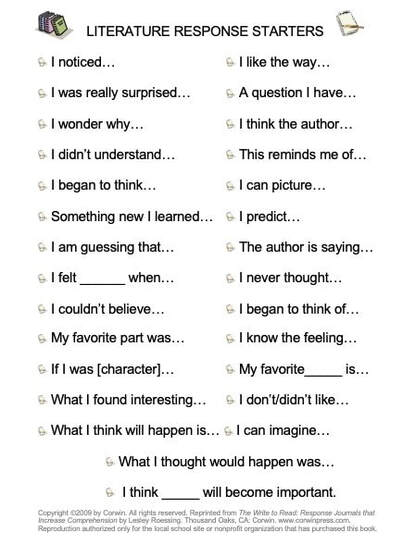

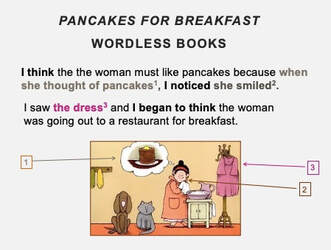

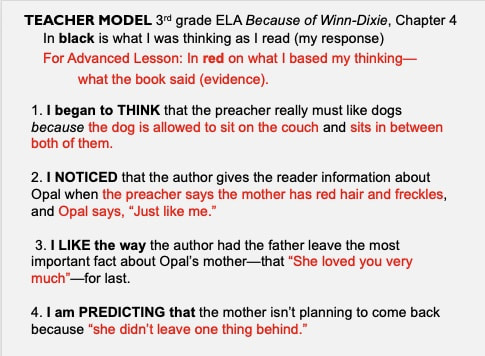

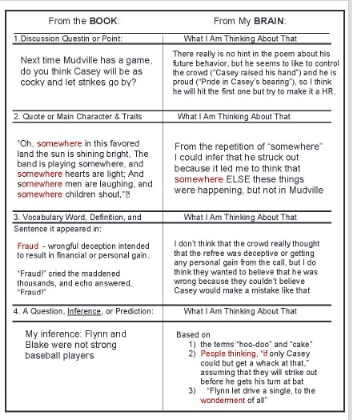

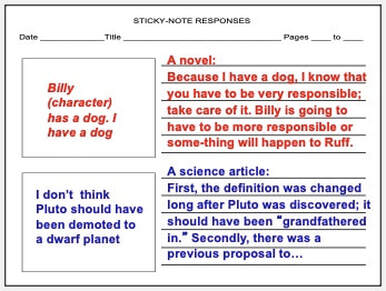

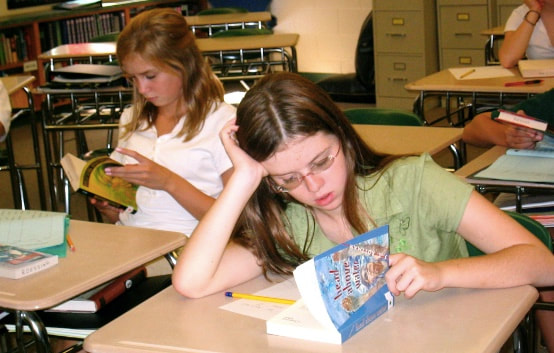

To be effective, Reader Response must be taught, modeled, and guided and eventually allow for reader choice. The purpose is to encourage readers to interact with text; the goal is increased comprehension. However, response should always be secondary to reading for pleasure and meaning and, therefore, the reason response is short and informal. Every reader’s 5-minute response will look different; some will be longer and deeper, demonstrating critical thinking; some will be shorter and show less more surface thinking (which will improve during the year). This is differentiation. I had some readers who wrote for much longer than 5 minutes because they wanted to share. They said they felt like they were chatting with me about their text. When some of my more proficient readers and writers wrote just a few lines, I responded, “This is not your 5-minute response. I will expect a bit more next time.” When more reluctant readers and writers wrote more than they had, I celebrated through a note in the journals. Courtney wrote about how her responding changed during the semester: I’m responding to what I read about the same amount but a lot deeper. My focus shifted from just taking the reading literally to thinking and analyzing it or making new comparisons to the world. Before, all my comparisons were to myself or other books, and now they relate to the outside world. A lot of my previous journal entries were questions and I didn’t respond to what I thought the answers were (which I do now). My recent journal entries have a lot more content than my older ones. Reader response journals also prepare readers for text discussion. In whole-class or small-group discussions, students can refer to their journals for points they can make. More reticent students can even read one of their responses as their contribution to a discussion. Reader Response is a timely topic, both because comprehension and adolescent literacy are crucial areas of concern and because response training leads to proficient performance on high-stakes reading and writing tests as students are trained to write critically and to respond to all types of literature, and texts fiction and nonfiction. I taught my student three types of response: BEFORE-READING RESPONSE, DURING-READING RESPONSE and AFTER-READING RESPONSE, all of which are essential to the process of interacting with, and learning from, text. BEFORE-READING RESPONSE Before-Reading Response (or Preview Response or, as I refer to it in The Write to Read, Anticipation Response) is crucial to activate prior knowledge, helping readers to make sense of new information and construct meaning from text. Also, Before-Reading Response prompts readers to set personal purposes for reading. Activating prior knowledge and setting a purpose for reading are considered two of the most valuable reading strategies. Another advantage is that Preview Response turns reading into inquiry: What do I know about this? What do I want to know? A Preview Response is a reflection based on previewing or skimming an upcoming text, focusing on text features, such as titles, authors, pictures, illustrations, subtitles, graphics—features that differ based on the text being previewed. Response can be oral or, more effectively, written. In a Preview Response readers make inferences about, and predictions of, what will be read, and such response can be effectively implemented in all disciplines with all texts. Below is (1) a Teacher Model based on the covers and Introduction of The Glass Castle, (2) Guided Practice with 4th graders getting ready to read George Washington's Sock, and (3) 8th graders preparing to read The Giver. >Read more about Preview Response, with examples from students reading science, social studies, and math texts, in “Before-Reading Preview Response,” one of my columns for AMLE Magazine and in The Write to Read: Response Journal That Increase Comprehension on which this blog is based. , DURING-READING RESPONSE During-Reading Response is response students write while they are reading a text. Effective written responses should be meaningful and compel readers to explore, question, and challenge text and make connections and inferences so they can construct meaning and learn from text. During reading response is short, personal, informal, exploratory, unedited, and ungraded. There are many formats for During-Reading Response. I scaffolded and taught each type, many of which I created for my students, through the first half of the year, based on analyzing what proficient readers do—maybe not on paper, but in their heads and in conversations with other readers. In this way, readers added to their “toolbelts” and towards the goal of deciding how best to respond in their journals based on their preferences and most appropriate for the texts they were reading. An academic team or self-contained teachers can start with one response strategy in ELA, then add social studies, then science, and then math, and health and art, so that students are responding to texts (including visual texts) across the curriculum. I worked with one school where, when I returned to train in After-Reading Response, the music teacher was having students respond to music and the football coach shared that he had players responding to diagrams of plays! I have found that the greatest problem with students’ responses at the beginning of the year is that readers, even my college students, tend to write summaries instead of reflections. After we discuss (respond) to a text orally, I hand out a list of Response Starters to add to their Reading Journals, and we examine them. We discuss some of the stems we heard in our class discussion, and students are encouraged to suggest others to add to the list. Students began with trying out some of the Response Starters in their responses, moving to the point where they just might choose one to begin their response which moves them away from the habit of summarizing into the response mode. Even our youngest students can read and respond to a wordless text. Visual readers point to the image that they are responding to, orally or in writing. (1) is an example of response to pictures and a Teacher Model based on a chapter of Winn-Dixie which the students had already read. > Read more about Response Starters, with examples from students reading a science article and a math word problem in “Reader Response In All Disciplines,” one of my columns for AMLE Magazine and in other content areas in The Write to Read: Response Journal That Increase Comprehension, the book on which the AMLE Magazine columns and this blog is based. ----------- There are a variety of ways readers can respond during their reading of the texts of all types, all of which help increase text engagement and comprehension. Some I adapted, and some I created, andI scaffolded them—introducing and moving on when students had successfully demonstrated the idea because the point was to give readers the options so they could choose the option that best fitted, which in some cases was a hybrid of strategies. MARGINAL NOTES Especially effective with informational text (and with reluctant writers) was a response that I referred to as Marginal Notes for which the teacher, or the class together, assigns logos—simple, easy-to-draw, and easy to remember symbols—to statement readers can make about text: \It is most effective to introduce readers to the concept of marginal notes by introducing and employing three logos with a text, such as an article, and when the students are familiar with those three, adding two more and then two more, until they are employing all logos as marginal notes to show their thinking. Students read an article marking a “note” or logo in the margin. Teachers can require a certain number spread out over the article, differentiating for different readers. Besides causing readers to interact with the text as teachers can observe if they walk around during the reading-marginal noting here are many options of what readers can do after they mark a text. Below is my Teacher Model for a lesson on Marginal Notes. >In my column on “Marginal Notes” for AMLE Magazine and in The Write to Read, there are a variety of student examples. DOUBLE-ENTRY JOURNALS Many teachers are familiar with double-entry journals or dialectical journal journals. I find them especially effective because teachers can see, and students can remember, to what text they responded, thereby making visible the reader's thought processes. The forms I designed included two columns: the left-hand column, labeled “From the Book,” presents the text evidence; the right-hand column, “From my Brain,” shows the reader’s thinking. The teacher can first model from a chapter or text the students have already read, such as my example from Mr. Popper’s Penguins with an elementary class or the poem "Casey at the Bat" with a secondary class. >In my column on “Double-Entry Journals” for AMLE Magazine are student examples from ELA, social studies, science, and math classes. The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension includes 6 different types of double-entry journals, depending on the Reading Focus Lessons being taught and a plain form for content area classes, and Talking Texts: A Teachers' Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum includes double-entry journals for Book Club readings and meetings. STICKY-NOTE RESPONSES Many teachers ask students to post sticky notes in their chapters as they read. The problem I found was that small Sticky Notes lead to small (shallow) thinking. This was my solution: After reading and sticking Sticky Notes in book, in class students can choose 3-4 Sticky Notes to place in the squares of a Sticky-Note Double-Entry journal (pictured) on left side; on right side, they further respond to their original response, thereby delving deeper and developing their thinking. In a way, this could be turned into a “triple-entry journal” if a column was inserted on the left for the text responded to. VISUAL RESPONSE or DRAWING THROUGH THE TEXT Responses do not always need to be in words. Proficient readers visualize as they read a text. They use the words from the text, in combination with background knowledge and prior experiences, connections from their lives and other texts, and inferences made, to construct mental images. When readers create images in their minds that reflect or represent the ideas in the text, they comprehend text at deeper levels and they retain more information and understanding. The most effective way to teach students to visualize is to teach readers to draw images as they read a text as a during-reading response strategy. It is important that readers include the words or phrases to which they are responding. I would even suggest a double-entry journal with lines for the text on the left side and blank spaces for drawings on the right side. The advantages of drawing as response:

>My Reader Response column "Ideas for Helping Readers Visualize Text to Promote Comprehension at Deeper Levels" includes teacher directions for this response activity. CONCLUSION As one can probably tell, I am passionate about employing Reader Response. Year after year, I observed my reluctant readers become real, even ravenous, readers, increasing their comprehension and raising reading levels. At the same time, I noted my proficient readers reading more deeply and critically. All readers had more to contribute to class and small-group literary discussions. Since my readers read more than they ever had before, it was obvious that reponse journaling did not curtail their new found-love of reading. A few words from my students: Stopping every 25 minutes to write allows me to reflect on the character’s actions, make connections, and understand why the author writes the way he does. I have also been exploring different genres of literature during my reading journals this year. I have read sports, adventure, mystery, historical fiction, short story collections, and comedy. Not only have reading journals helped me in just my reading comprehension, but it also has improved my writing skills. Analyzing the author’s style influences my own methods of writing. -John (from The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension) and I have to say I’ve evolved as a reader. I think it’s because reflecting on reading really got me thinking about what I read. Now it was more than just words in a book. It was like entering a different world every time I picked up a book. -Carly (from The Write to Read: Response Journals that Increase Comprehension) Another advantage for me and for my readers is that I never felt the need to quiz or test their reading or comprehension of texts. The evidence was in their journals. See PART 2 AFTER-READING RESPONSE

5 Comments

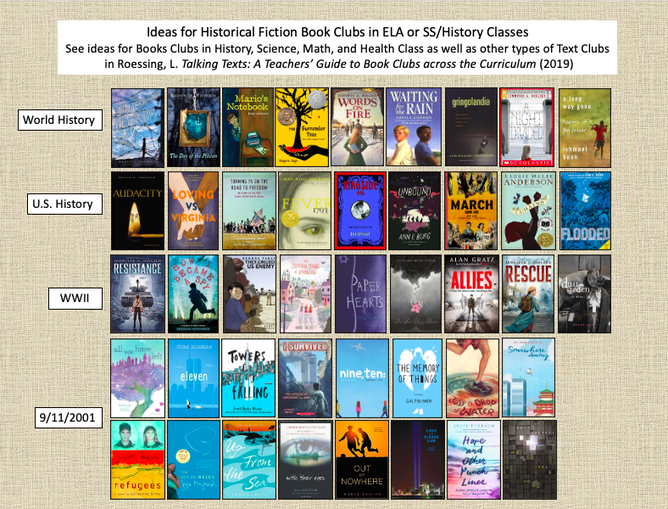

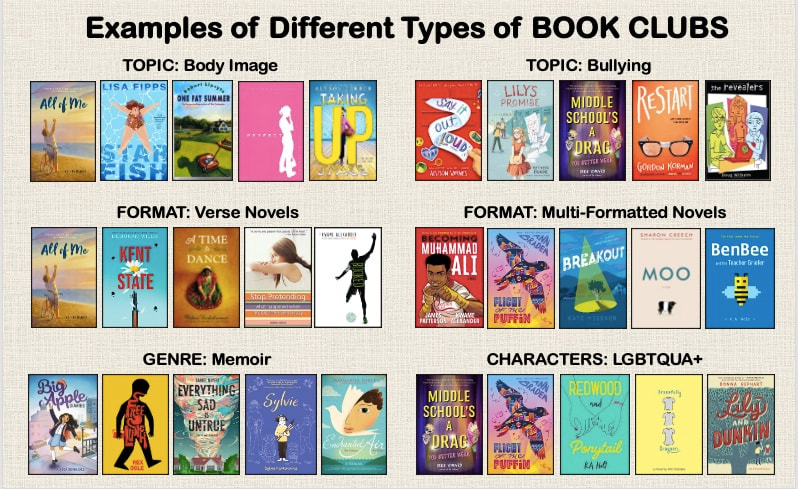

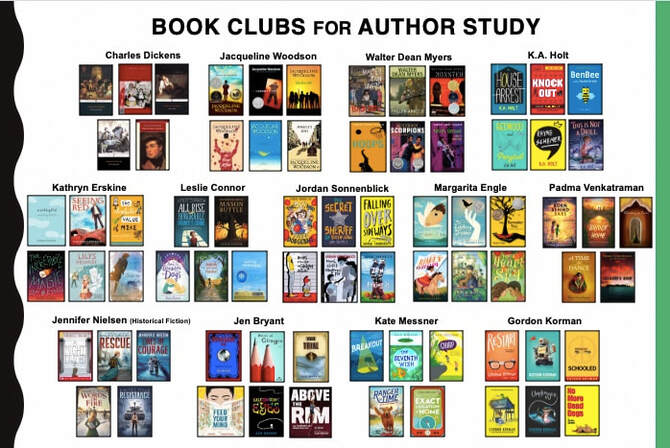

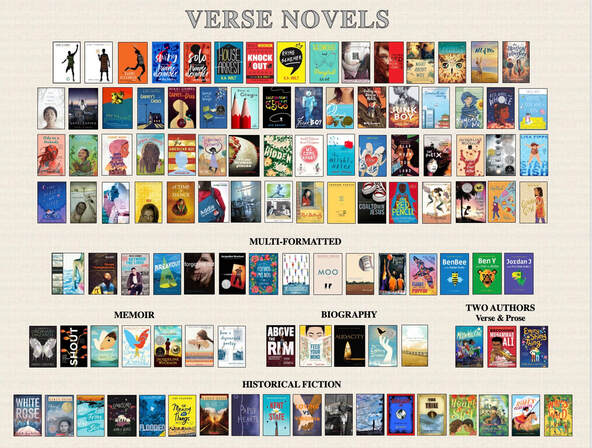

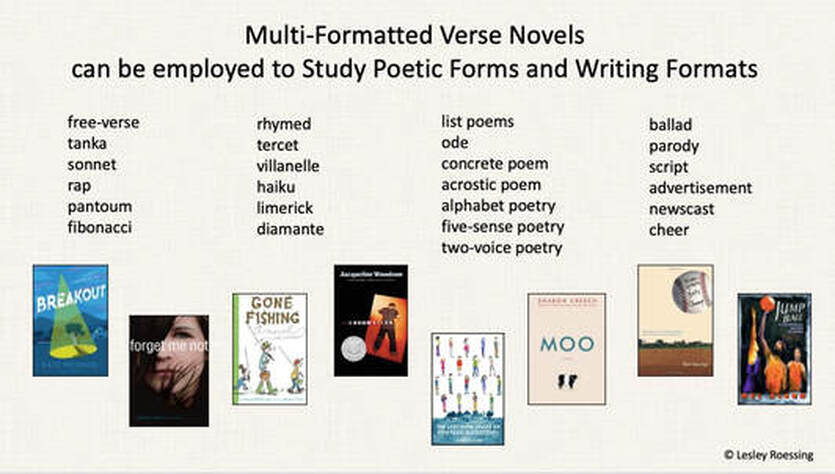

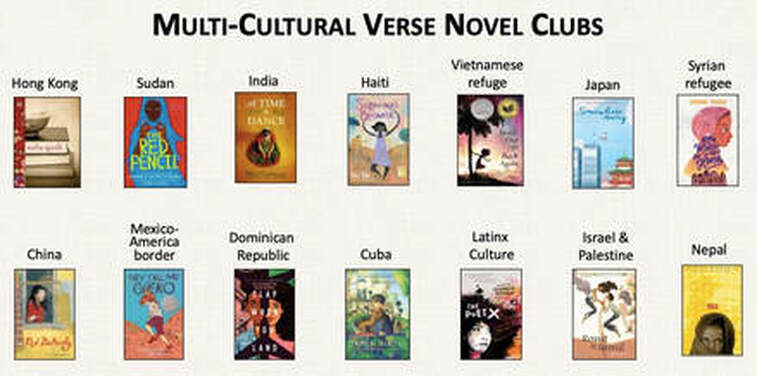

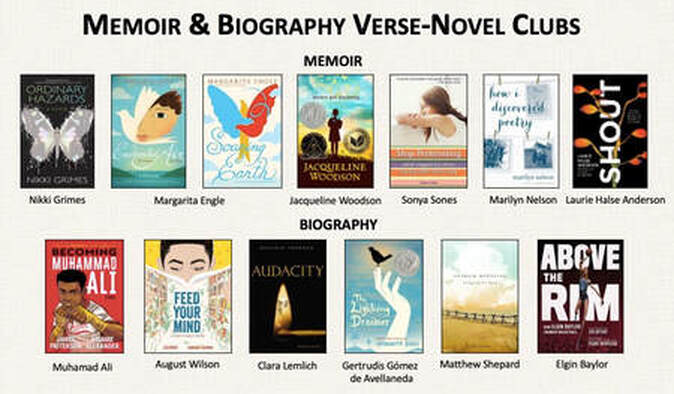

Text Clubs have many advantages which I have written about in the introduction to the Book Reviews section. Besides Nonfiction or Informational Book Clubs, Short Story Clubs, Poetry Clubs, Folklore Clubs, Article Clubs, and even Textbook Clubs, all of which are described in Talking Texts: A Teacher’s Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum, Novel Book Clubs are the most familiar type of Book Club and can be organized in a variety of ways. These are some suggestions for choosing books for Book Club reading. AUTHOR STUDY BOOK CLUBS As I share in Talking Text, my first book club was a matter of necessity. It was 1989 and, other than my mother’s monthly book club, I had not heard of the practice used in the classroom but in my first job which was that of a 11-month permanent substitute, my curriculum guide for Senior Honors stated that I was to teach a Dickens novel. Looking around the classroom I found about 5 copies of one novel. Going to the library, I found a few copies of other Dickens novels. Searching, borrowing, and purchasing, I came up with 5-6 copies of five novels written by Charles Dickens. And so my first Book Club adventure began. I taught background on the author and his times, the students each chose a novel to read, and Author Study Book Clubs were formed. After each group read and discussed their novel, they prepared a creative presentation to the class. In that way, students read one novel but learned about five. Author Study Book Clubs can be structured in a variety of ways. Then teacher can give background on the author or students can individually or later, in book clubs, study different biographical facets of the author, including time period, geography, cultural background, other publications, etc. which they will share with their clubs and later with the class. The class can read a whole-class text written by the author, ideally a short story. Or the Book Clubs can choose books based on teacher book talks and/or looking at the covers and skimming a few pages of each book. [See Talking Texts for more in-depth information on forming book clubs.] As with the Dickens Book Clubs, each book club read and holds 4-5 meetings to discuss their reading and then prepare a presentation to the class in which they include their observations on not only the content by the author’s craft. Books clubs can compare and contrast the author’s writings as a class or in Inter-Book Clubs where one member of each book club meets in a group to compare and contrast and report their findings. How to choose an author? The most effective is to choose authors who have published at least 5 texts. Ideally the author would have published a short story that the class and read together to begin and build on, but that is rarely the case. I find that it is effective to find authors who write in different genres, such as Walter Dean Myers who has published memoir, historical fiction, realistic fiction, “street life” fiction, sports fiction, and romance, as well as collections of short stories (which are good for slower, more emergent readers who may not be able to finish an entire novel in the same time period as their peers. Also it is best to choose an author who has written in a variety of reading levels. More rare but effective would be to choose an author who has written in a variety of formats, such as prose, verse, graphic, and multi-formatted, such as Laurie Halse Anderson who wrote the graphic novel Wonder Woman: Tempest Tossed but her novel Speak was re-written as in graphic form. Or an author such as Jennifer Nielsen who has written historical novels taking place in different time periods. If you cannot read the titles, look up the author on Goodreads for titles and synopses.  FORMAT BOOK CLUBS In Format Book Clubs book club members read books written in the same format, such as verse novels, graphic novels, epistolary novels (or now, novels written through letters, emails, and/or texts) or, gaining in popularity, multi-formatted novels. Format Book Clubs allow teachers to teach focus lessons on the format. VERSE NOVEL BOOK CLUBS For example most novels-in-verse are written in free verse, so the teacher can teach that format but also poetic devices such as figurative language of all types. I think the power of free verse is in the line break choices. I always described line breaks as an eye-pause, when reading it is short than a comma but your eye is forced to pause and notice a particular word or phrase. Discussion can be held on why the author chose to break on that word. Stanza length, which usually varies, inspires other reflective conversations. Verse novels are written in most genres, such as historical fiction, memoir, biography, humor, realistic fiction. Some authors only write in verse format; others write in a range of formats. Such novels are written by culturally-diverse authors on diverse topics, featuring diverse characters and settings. Many verse novels are written in a variety of poetic forms which lead to lessons or study of the different types of poetic formats. Leslea Newman’s October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard is written as 68 poems about Matthew Shepard and his murder. A range of emotions is shared through a variety of poetic styles: free verse, haiku, pantoum, concrete, rhymed, list, alphabet, villanelle, acrostic, and poems modeled after the poetry of other poets, thereby, not only introducing to the “what” of those formats but the “why.” But most importantly, novel-in-verse is a text format which engages readers for divergent reasons:

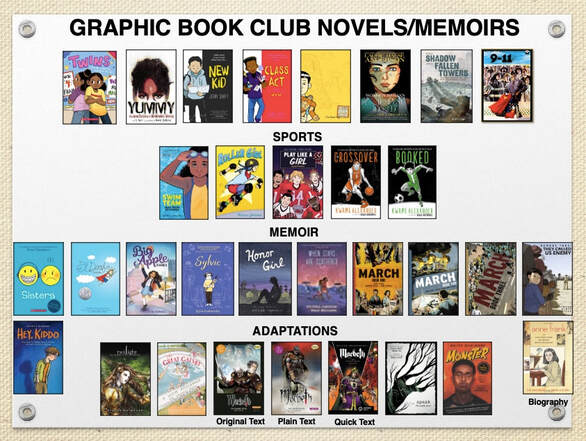

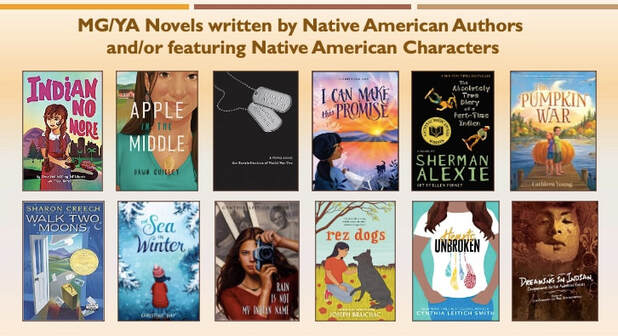

GRAPHIC BOOK CLUBS It is important that teachers teach visual literacy. Citizens of the world are bombarded with images daily—in the news, as advertising, body language and facial expressions. Reading and studying graphic text allow readers to learn to read visual clues. The advantages of holding Graphic Novel Clubs are that, besides engaging many reluctant readers, artistic students will learn to appreciate the congruity of art and text and the graphics make it possible for our ELL readers to interpret a text. I have not read many graphic novels but teachers/librarians can facilitate Graphic Book Clubs with an assortment of graphic texts as shown or hold Graphic Historical Fiction Book Clubs or Graphic Memoir Book Clubs. CULTURAL BOOK CLUBS Besides advocating for diverse cultures to be represented in Book Club choices, Cultural Book Clubs can be developed around the cultures of the author, characters, or setting. Pictured are some examples. It is vital that readers see their cultures reflecting in stories they read as well as using story as passage into other cultures. This type of Book Club can lead to research into cultures which Clubs will then present to their peers who may be reading novels set in, or featuring characters representing, other cultures.  GENRE BOOK CLUBS Genre Book Clubs can facilitate students exploring a genre and to see the variety of topics that can be covered by a genre. When planning a genre study, it is effective to include diverse authors and/or characters and formats—not only prose, but verse, graphic, and/or multi-formatted. Genre Book Clubs can be created around Historical Fiction, Sports Fiction, Memoir, Mystery, Science Fiction, Fantasy, Dystopian, Magical Realism, etc. Historical Fiction novels can be read and discussed in Social Studies/History classes or in ELA/English classes or as part of interdisciplinary units in both. One suggestion is that in a Social Studies class, each Historical Fiction Book Club reads a novel from a different time or place that will be covered in the curriculum that year, and, when that time/place is being covered in class, the Book Club makes their presentation to the class or all Book Clubs present at the end of the year as a review. STEM BOOK CLUBS Not really considered a genre are Disciplinary Book Clubs—math, social studies, science, health, art, music. The novels pictured include science and math connections and can be read in those two classes or in ELA or English classes with collaborative interdisciplinary lessons. Some of them, such as Fever 1793, can be employed across the curriculum. THEMATIC BOOK CLUBS

The most obvious organization for Book Clubs is Thematic or Topic Book Clubs and most of what I share in Facebook posts and in the Book Reviews sub-sections of this site are Thematic Book Clubs, such as those posted under the Book Review section: Teen Justice & Change Seekers and Surviving Loss. Other topics or themes around which I have planned Book Club reading are

MONTHLY BOOK CLUB TOPICS I wrote a guest-blog for the Western Pennsylvania Council for Teachers of English (WPCTE) on monthly Book Club topics that are based on National and International Days and Holidays, “2022 MG/YA Book Recommendations Month-by-Month.” Part 2 of that blog includes a link to Part 1. These suggestions for ways to choose books for Book Club reading gives the readers a commonality that they can discuss across the Clubs and across the class. When Book Clubs have something—characters, format, genre, topic—they can compare and contrast, one student from each Book Club can meet together, conducting discussions in these Inter-Club meetings, giving even more meaning to the reading. See these ideas described, developed, and extended and even more Book Club ideas and strategies in Talking Texts: A Teacher’s Guide to Book Clubs across the Curriculum. |

AuthorSee "About Lesley" Page Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed