- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

- Asian, Asian-American

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

|

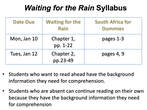

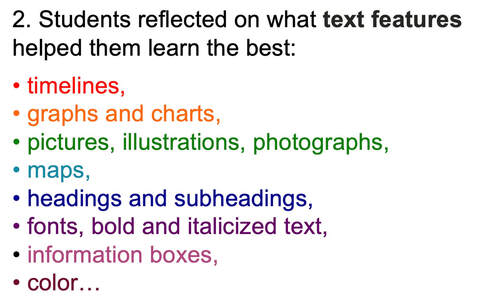

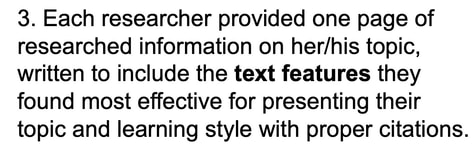

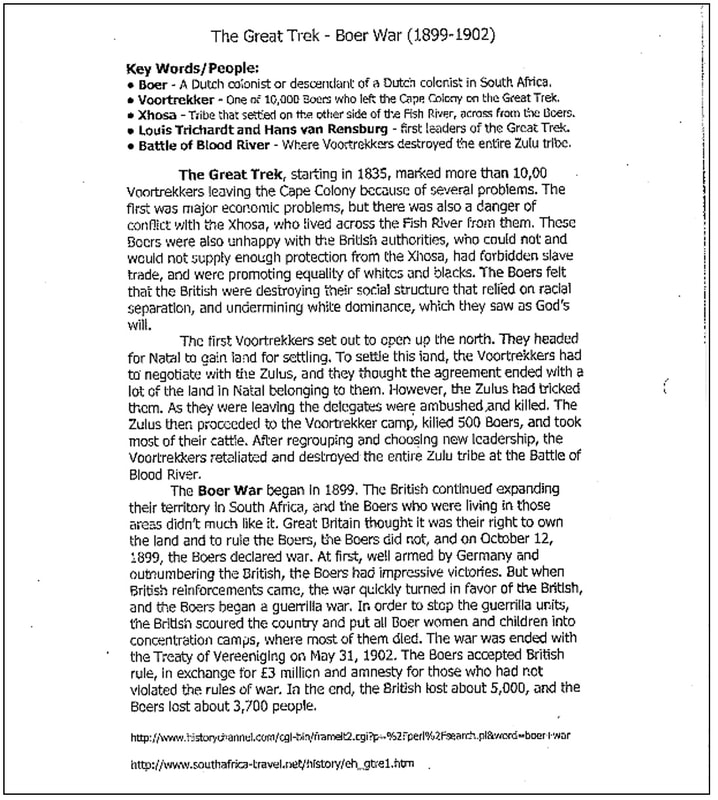

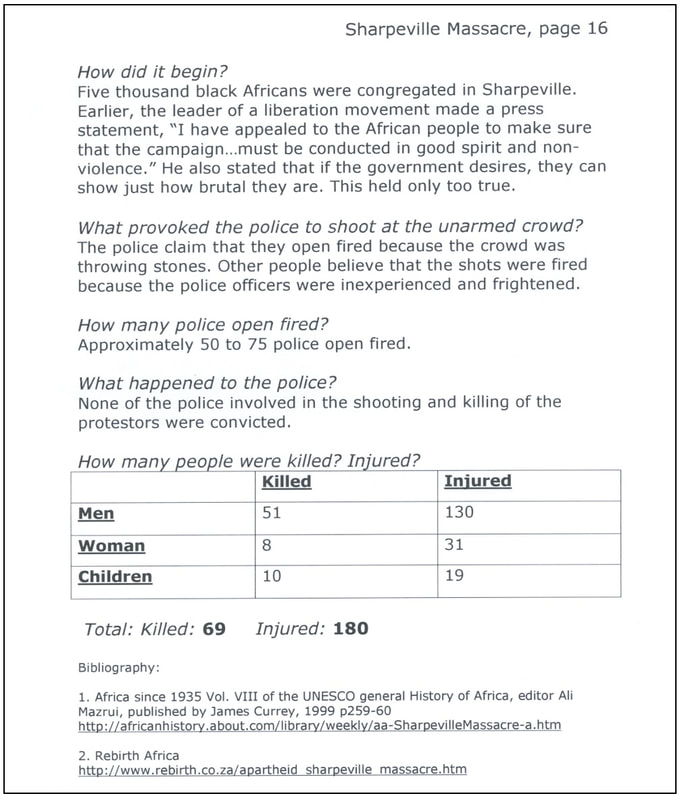

We were going the read Waiting for the Rain, a novel about Apartheid in South Africa, and my readers would need background information about Apartheid before, or as, they read this novel. It was a time period completely foreign to them. I also wanted my students to practice researching, taking notes, distilling information, and presenting that research to others although not orally. I had found that in the oral presentations, some of the class was going over their presentations in their heads, some were celebrating the fact that they had finished their presentations, presenters were using words and names unfamiliar to the class and which they would not recognize later, and, yes, some were listening, but would not remember the information when it was needed when reading they pertinent chapters in the novel. In addition, I wanted the class to be able to use that research. I wanted the research to matter. Most of the time when a student researches, two people benefit: the student-researcher and the teacher who reads the research paper or evaluates the research project. Since the adolescents were unfamiliar with Apartheid, they had no burning questions. More importantly, they would need the information from each other’s research when we began reading the novel. How could I make sure that their research was available for all to use? I thought about what I do whenever I come up against new knowledge that I need to learn and use, like learning Power Point. I go out and buy a book, a book that I, with no prior knowledge and little technical background, can understand. Many times I buy a Dummies guide. I bought The Dummies’ Guide to Power Point. And I put it on the bookshelf right next to The Dummies’ Guide to Wine and, yes, even The Dummies’ Guide to Shakespeare. With that thought, the idea was born! I decided that the class could write a guide to Apartheid to which all of us could then refer as we read the chapters of our novel. Not only would that solve the “usable” research quandary, but it would also solve my second research-based dilemma: how to teach students to avoid plagiarizing, even inadvertently. No matter how well-intentioned my students were, and no matter the number and variety of resources required, they still could not figure out how to put research into their own thoughts and words. What I wanted to teach them was to read the sources, conducting an investigation to find facts or discover theories that they would then write about with authority. One step towards that goal was to invite them to write for an audience of their peers (the “Dummies,” so to speak). They found that they had to evaluate the importance of facts found as well as needing to explain the information, sometimes using extra resources and talking to experts (other teachers). It no longer mattered that they previously knew nothing about the topics they were investigating. I have found that one has to be a learner to be a more effective teacher. The students’ goal became to write a resource that their classmates could understand and use as we read Waiting for the Rain. The class planned out their book; in this case, since I was familiar with the novel, I advised them what needed to be included. The students made up their Table of Contents and divided the topics. Next they brainstormed what text features make textbooks and resource material effective and user-friendly; they discussed titles, subheadings, glossaries, charts, maps, pictures, captions, graphs, and timelines as they looked through their textbooks and other nonfiction texts. They also identified formatting features: bold and italicized text, font choice and size, and justifications. South Africa for the Dummy was created. And written. The students were now not only researchers, but authors; they thought about their writing as authors think about writing—how it sounds, how it looks, and what it communicates. Once published, the guide was used. Everyone got a copy. We referred to Sarah’s pages when Frikkie’s uncle, Ooms Koos, mentioned the Boer War. When Joseph told Tengo about passbooks, we read Debbie’s pages about the Population Registration Act and Tom’s section on discriminatory laws. As the setting of the novel moved to Johannesburg, we looked at Amanda’s maps and John’s information on Jo’burg and the townships. We understood Joseph’s agony over the Sharpeville Massacre, and we knew of the work of Steve Biko even though he is not mentioned in the novel. For once, I was not doing the talking and the teaching; I was not spoon-feeding the information.  On their reading syllabus, it stated “February 10: “Soweto,” Dummy, p.24; Chapters 15-16, Waiting for the Rain.” We would refer to the articles (and authors) in class discussions. “Well, in his article on Nelson Mandela, Steve said that….” An added advantage was that students did not have to follow the syllabus. If they wished to read ahead, they now could; they had ready access to the background information necessary to comprehend the text. All authors’ research was being seen and valued by their classmates. The was no need to threaten grades or rewrites to elicit enough information or proper formatting or thorough editing; they were facing an even more critical audience—their peers. Teachers need to look for, and even create, opportunities for students to write for real audiences, audiences who care what is said and how it is written. In today’s world of email, text messages, and instant messaging, these occasions don’t readily occur. The following year some of the students returned from the high school to tell me that they had read Cry, the Beloved Country and used their Guide to more deeply understand that text and to study for the test. Our book demonstrated that research does matter. ADVANTAGES • Research skills for authentic use and audience • Makes every student an expert • Informative/Explanatory writing • Meta-cognition - analysis of Text Features and impact on individual learning styles • Independent research and individual writing for a collaborative project (small-group assignment for differentiation) Note: An advanced step required by CCSS is to study, analyze, and imitate text structures in mentor texts – compare/contrast, cause/effect, chronology, problem/solution, etc - and include in pages. This Blog was excerpted, revised, and updated from Roessing, L., Making Research Matter, The English Journal, Vol. 96, No. 4 (Mar., 2007), pp. 50-55

1 Comment

|

AuthorSee "About Lesley" Page Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed