- INTRO/SITE CONTENTS

- MY PUBLICATIONS

- BLOG

-

BOOK REVIEWS

- PLANNING A DIVERSE LIBRARY

- Surviving Loss & Abandonment

- Historical Fiction

- Sports Fiction

- Justice & Change Seekers

- Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Latinx & Hispanic Characters

- Bullying

- Acts of Kindness

- STEM Novels

- Identity & Self-Discovery

- Winter Holidays

- Contending with the Law

- Family Relationships

- Stories of Black History

- Read Across America

- Verse Novels

- Immigrant/Refugee Experience

- Strong Resilient Girls in Literature

- Asian, Asian-American

- Novels featuring Contemporary Jewish Characters

- Multiple Voices & Multiple Perspectives

- Short Readings: Stories, Essays & Memoirs

- Graphic Novels

- Physical Challenges & Illness

- Characters Who are Adopted or in Foster Care

- Love & Friendship

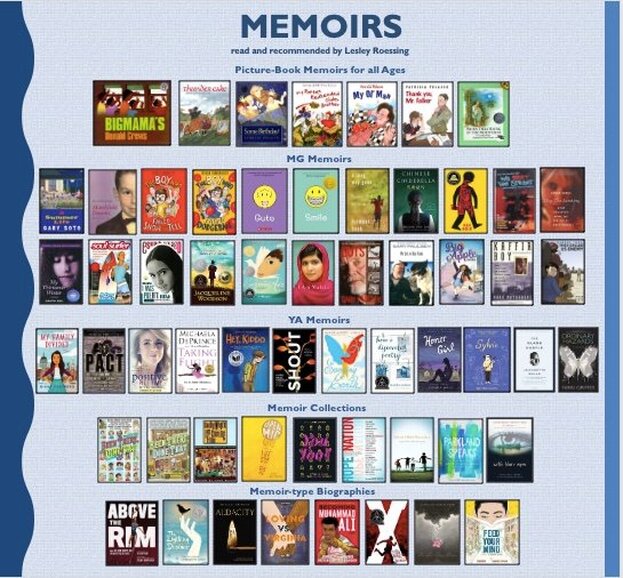

- Memoirs

- STRATEGY SHORTS

|

We write for many reasons—to entertain, to inform, to persuade, to enlighten, to show what we learned, to find out what we know. But the most important reason our writers can write is to discover who they are and to reflect on the people, places, objects and mementos, and events that made them the persons they are and the adults they will become. In other words, memoir writing. As writers learn about themselves while “researching” and writing their memoirs, memoir writing becomes inquiry. And memoir writing becomes a journey of self-discovery. Why Teach Memoir Writing?

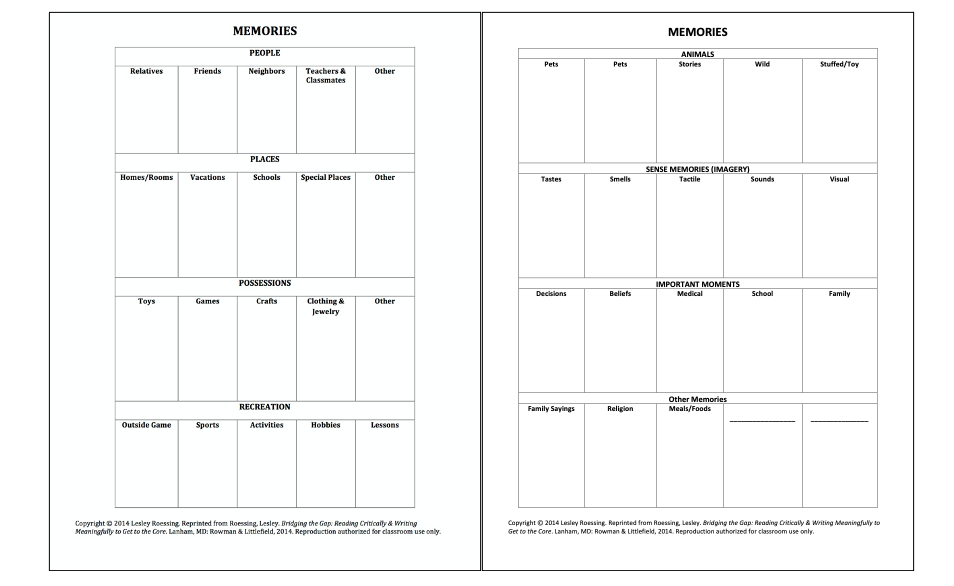

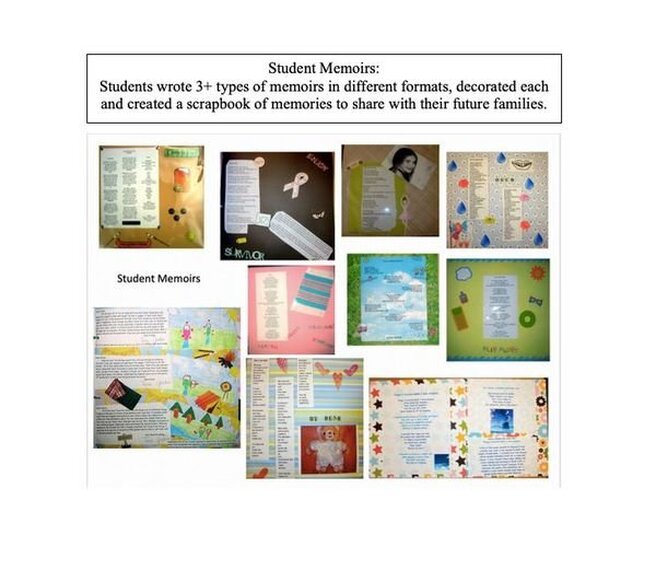

How to Teach Memoir Writing: Using Mentor Texts Like any writing, memoir writing is taught by first reading mentor texts. Memoir as a literary genre is experiencing great popularity, and memoirs are available in diverse reading levels and genres and on a wide variety of topics. There are memoir picture books, such as those written and illustrated by Patricia Polocco. There are memoir poems. i.e., George Ella Lyons “Where I Am From” which has developed into a genre of its own; Dolly Parton’s lyrics for “Coat of Many Colors” became a picture book (Parton, 1996); Cynthia Rylant’s free verse poetry collection about her home in Beaver, West Virginia, collected in Waiting to Waltz (2001). Graphic memoirs, such as Persepolis (Satrapi, 2004) or El Deafo (Bell, 2014), have become popular with many readers and writers. There are prose memoirs in essay length and novel length. And there are oral memoirs and video memoirs. Student writers read a memoir and analyze what the author wrote and how the author wrote, deconstructing those texts to discover how authors develop their writings. After the teacher demonstrates how to take those deconstructed elements and reconstruct them into a memoir, the students are ready to brainstorm their own topics and draft. I like to begin with an oral text, such as the Jerry Seinfeld’s “Halloween,” the story of Seinfeld’s childhood Halloween experiences and costumes. As the students listen to this memoir from the CD included in Seinfeld’s picture book Halloween (2008) or watch the story unfold on YouTube, they jot down the elements they notice, such as dialogue, narration, specific details, description, names and other proper nouns, humor, point of view, topics, humor, onomatopoeia, similes, reflection. After the class creates an anchor chart of elements effective for memoirs, students read a short written text to deconstruct. For example, looking at the first few lines of George Ella Lyon’s poem “Where I’m From” (1999), students are asked to note what they notice about what and how the memoirist writes. Charlie starts. “I notice smells, ‘Clorox and carbon-tetrachloride.’ I am not sure what carbon-tetrachloride is, but I am picturing a chemical smell.” We look it up and find out that carbon-tetrachloride was used in dry-cleaning establishments. A biography of Ms. Lyon reveals that her father worked as a dry cleaner, and students infer that either her father came home from work smelling of the chemical or she visited him at his business. Either way, that smell takes her back to her childhood. Another student chimes in, “Clothespins, Clorox, and carbon-tetrachoride are sort of like alliteration—almost the same beginning sound.” We talk about what activity the Dutch elm’s “long-gone limbs” suggests and infer that as a child, the author liked to climb that tree. Students observe that people’s names are included in the memoir, and a student says “Imogene and Alafair sound a little old-fashioned, so they could be parents or grandparents,” and others notice the family sayings, such as “Perk up.” We then share maxims from our own families. How to Teach Memoir Writing: Brainstorming and Drafting After noting that “Where I’m From” was created from a variety of childhood topics, such as people, places, events, activities, environment, religion, family sayings and stories, and foods, we all brainstorm topics from our childhoods, collecting them on a Memories Chart [see below] to help elicit ideas for writing. Using a projector I fill in my chart, relating a 1-minute story about each entry, as students fill in their charts. Some students glance up at my chart and listen as they become stuck; others stay focused on their own charts and tune me out. My demonstration is for those who need it. I clarify that not all the categories will have entries, and they need not fill in topics in any order. Over the next days as we read more mentor texts and share more personal stories, writers can add topics to their charts (Roessing, 141-142), gathering ideas for the memoirs they will write. As the next step I composes a short memoir employing some of the same elements and techniques that we have noticed in our two mentor texts. Since at this point we have only heard Jerry Seinfeld’s monologue and read George Ella Lyon’s memoir, I draft my memoir, following much of the poet’s structure and employing many of her techniques, adding a few elements from our analysis of “Halloween.” I am from King-on-the-Mountain, Hide & Seek, Statues, and Tag, Calling out “I’m It” or “I win!” And splish-splash-ing in puddles on rainy days. I am from maples trees and weeping willows, Big back yards, each with a swing set and sandbox, Playing in portable pools on sunny days and Putting pennies in the patio cement as we build our porch.… Students then analyze my memoir, noticing how it employs topics, literary elements, and some writer's crafts from the mentor texts but also how it differs to reflect my memories and writing style. Over the next few days I introduce the students to other memoir mentor texts while they read full-length self-selected memoirs* either independently or in book clubs, add topics to their lists, expand the class anchor charts, and draft short memoirs in a variety of formats—prose, different styles of poetry, and graphic—shadowing the exemplars read. After students have sufficient ideas and content and they are ready to choose the topic(s), types, and formats for one of their memoir drats to take to the publishing stage (or more in a longer unit), they revise based on daily revision mini-lessons on the traits—organization, word choice, voice, sentence fluency, and finally edit based on convention lessons taught in class. An important focus lesson we will cover is the reflection that generally comes at the end of a memoir. We again look at mentor texts. We examine the ending of “Where I’m From” as well as endings to prose memoirs, such as Cynthia Rylant’s When I Was Young in the Mountains (1993). When I was young in the mountains, I never wanted to go to the ocean, and I never wanted to go to the desert. I never wanted to go anywhere else in the world, for I was in the mountains. And that was always enough. (last page) One student combines our lessons in her final memoir (Roessing, 2014, p. 77-78): "Where I Am From" by Janel (based on G.E. Lyon’s poem “Where I’m From”) I am from bar-b-que, From corn-on-the-cob and mac-and-cheese. I am from mowed grass and tall trees. I am from the never-finished playground That has no swing or benches As if time stood still before my eyes. I am from teachers and scientists, From Mandela and Martin Luther King. I’m from “Don’t do drugs” And “Stay in school.” From "Respect" and "Be tactful." I’m from “Thank you, Jesus” From children’s church And the gospel songs I’ve heard many time before. I’m from word games and puzzles, Road trips and airplane rides. But also from drive-by shootings And trying to stay alive. In my room are boxes Toppling over with old pictures - A time when I lived With no cares at all, A time that I will never forget And never want to erase. While this writer followed Lyon's format somewhat closely, others had the confidence to move in divergent directions. Conclusion I have not included much about the drafting phase because the memoirs almost write themselves. If teachers help adolescents to think back and remember and reflect on their pasts through reading the memoirs of others and sharing their childhood stories within the classroom writing community, after analyzing texts and brainstorming, stories pour out. I am always amazed that this is one unit for which all my students have written and all have done their best writing of the year. Students have written about persons, places, mementoes, events, crises, and discovered photographs. Writers have published their memoirs as rhyming poems, free-verse poetry, limericks, sonnets, prose narratives, plays, and graphics. They have shared unbelievably personal stories, such as “The Day Daddy Left,” and humorous stories, such as “Beastie.” But most importantly, adolescent writers have perceived themselves as authors as they wrote with voice, cared about their writing, and discovered meaning in their lives as they learned about themselves, writing what matters.  More teacher models, student examples (along with lessons, mentor texts, and reproducible forms for brainstorming) can be viewed in Bridging the Gap: Reading Critically & Writing Meaningfully to Get to the Core. *Memoir Reading while Memoir Writing How is memoir writing supported by memoir reading? Reading memoirs provides mentor texts for writing memoirs. As readers read about people, places, objects, and events which are meaningful to published memoirists, they can notice and note how the memoirists write about these topics, using authors as mentors for their writings. Memoirs appeal to all readers because they are available at all reading levels and lengths; on all topics from dancing to sports to survival and resilience; in many formats, including prose, free verse, graphic, multi-formatted, and even as rhyming poems. Memoirs are written in first and third person, and can be humorous, poignant, and enlightening. Readers can together read whole-class memoirs, participate in memoir book clubs or memoir essay clubs, and read self-selected memoirs individually. In addition to memoirs, there are novels, such as Front Desk, that closely follow the author’s life, and there are biographies written in the style of memoir in that they focus on a particular part of a person’s life or particular events based around a theme and emphasize personal experience, thoughts, feelings, reactions, and reflections rather than facts.  Picture Book Memoirs: Bigmama’s; Patricia Polacco’s memoirs; When I Was Young in the Mountains ES/MG Memoirs: A Summer Life; Marshfield Dreams; The Boy Who Failed Show and Tell; The Boy Who Failed Dodgeball; Guts; Smile; A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier; Chinese Cinderella; Free Lunch; We Beat the Streets; Stop Pretending: What Happened When My Big Sister Went Crazy; My Thirteenth Winter; Soul Surfer; When I Was Puerto Rican; Brown Girl Dreaming; Enchanted Air; I Am Malala; Guts; My Life in Dog Years; Big Apple Diaries; Kaffir Boy; They Called Us Enemy YA Memoirs: My Family Divided; The Pact; Positive; Taking Flight; Hey, Kiddo; Shout; Soaring Earth; How I Discovered Poetry; Honor Girl; Sylvie; The Glass Castle; Ordinary Hazards Memoir Collections: Been There, Done That; Going Where I’m Coming From; Open Mic; You Too?; Hope Nation; When I Was Your Age; Parkland Speaks; With Their Eyes: September 11th—The View from a High School at Ground Zero Memoir-type Biographies: Above the Rim; The Lightning Dreamer; Audacity; Loving vs Virginia; Becoming Muhammad Ali; X; The Last Cherry Blossom; Feed Your Mind References

Bell, C. (2014). El Deafo. New York: Harry N. Abrams. Lyon, G.E. (1999) Where I’m from. Where I’m from: Where poems come from. Spring, TX: Absey & Company. Moore, J. (2014). Where I am from. As in Roessing, L. Bridging the gap: Reading critically and writing meaningfully to get to the core. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Parton, D (1996). Coat of Many Colors. New York: HarperCollins. Roessing, L. (2014). Bridging the gap: Reading critically and writing meaningfully to get to the core. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Rylant, C. (2001). Waiting to waltz. New York, NY: Atheneum/Richard Jackson Books. Satrapi, Marjane. (2004). Persepolis: The story of a childhood. New York, NY: Pantheon. Seinfeld, J. (2008). Halloween. New York, NY: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers. The ideas and examples for this article were based on Bridging the Gap: Reading Critically and Writing Meaningfully to Get to the Core.

3 Comments

Lori C

1/2/2023 05:22:25 pm

This post inspired me. I was already planning a quick write personal writing, but now am excited to grab some resources mentioned here and stretch into a unit. Thank you!

Reply

Your blog, "Memoir: Writing about What Matters," is truly a captivating and insightful exploration of the art of memoir writing. The title alone suggests a deep understanding of the profound impact that personal stories can have. Your ability to convey the importance of capturing meaningful moments and experiences shines through, making it clear that your work is not just about writing but about delving into the essence of what truly matters in life. The thoughtful and engaging content undoubtedly resonates with anyone passionate about the power of storytelling. Keep up the inspiring work!

Reply

Ready to turn your goodwill into world-changing impact? 🌎✨ Dive into our guide on the 'Best Ways to Find and Decide Which Charities to Help.' 🌟 Uncover the secrets to purposeful giving, navigate the sea of causes, and discover how your generosity can leave a lasting legacy. This blog post is your passport to impactful change—where each click is a step towards making a difference that truly matters. Join us on this inspiring journey, and let's redefine the art of giving together. Your philanthropic adventure begins here.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSee "About Lesley" Page Archives

June 2024

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed